My idea for a research project with Monteverdi as a central theme originated when I led the Early Music department of the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague. To open more possibilities for the students in historical performance exploring new music specially written for them, plans were made for a sequel to an explorative project, mixing early and new music. That project was George Frederic Handel’s serenata, Parnasso in Festa, performed in the Grote Kerk, The Hague, at the Handel/Princess Anna of Hannover celebration in the 2009 festival year. In this project, students of composition teacher Cornelis de Bondt replaced parts of Handel's music with their own creations, maintaining the original libretto. This libretto tells the story of Thetis and Peleus. Not an opera, but rather a ‘festa teatrale’. The mythological ingredients of this piece had been made suitable for the wedding ceremony of Anne of Hannover and stadtholder William IV, by including some substantial scenes with other protagonists like Orpheus and Apollo. The cast of star singers for the nuptials was already present in London because just two weeks earlier, they had performed Handel’s Arianna in Creta in the King’s Theatre. Subconsciously, a lot of these narrative facts would later turn out to have an embryonal function in my own artistic research project.

As the organiser of the Handel Festival 2009 in The Hague and, more importantly, as head of the department performing its music, I was very close to the creative process of the festival production. After a next very successful school production in 2010, Monteverdi’s Vespers conducted by Charles Toet, also performed in Italy at the location of origin in Mantua, I was determined to have theatrical music of this composer as our next mission.

Soon, it was clear that doing something with the incomplete surviving opera Arianna, was the most attractive option. The part that was still there and even survived in print, the Lamento d’Arianna, could be serving as a very strong lead towards interesting new music drama.

Before working out a concept under the name The completion of Arianna, it became clear that this had been done by Alexander Goehr in 1995. It was interesting to read about his procedure of composing, by first setting the libretto in a mock Monteverdi style, and subsequently replacing this by his own inventions. But, I did not feel like attempting a similar procedure.

In the meantime a collective of composition students were recruited by Cornelis de Bondt, all interested to invest in a new opera project. De Bondt himself, however, was absorbed by the struggle with Dutch governmental destruction of our cultural life by cutting almost a quarter of the national budget, with huge consequences for almost every branch of culture and its education. He was more interested in an opera with Giorgio Agamben’s Homo Sacer as a point of departure. The isolated position of men in a discursive relationship with politics and the organisation of law, sovereignty, power and the concept of body would be the main themes in this operatic narrative. At that moment, I was already captivated by Monteverdi’s letters and started to imagine his person coming to life in a film or on stage through the wording of the letters and their content. There was certainly common ground with Agamben's theme, especially where the struggle with authorities and laws was concerned. I was increasingly intrigued by the conflict between Monteverdi and Artusi and the whole of its exhibitionistic theatricality.

At the same time as these exploratory efforts were made to launch a new hybrid opera project with old and new music, I was preoccupied with another research project of an epistemological nature. It concerned propositions for making a shift in dealing with knowledge in education and integration of embodiment in cognition rather than prolonging the old-fashioned dichotomy of body and mind. Through that research, I became acquainted with the theories of Michael Polanyi about tacit knowledge. What struck me was the way he addressed the struggle of the practitioner or the connoisseur to make others believe and trust their expertise and refrain from demanding explanations. We don’t ask a pilot or a surgeon first to explain what they are doing and how before we put our lives in their hands. Why would we ask these impossibilities from artists if there is no threat? The only answer we could give is that experiencing art might be the destination of their flight or the reason to live a bit longer after surgery to discover the meaning of that life, inspired by art.

From then on, I had a hunch that both branches of research were very much related and offered an opportunity to explore their common ground more deeply. Monteverdi's letters articulated several very recognisable issues, for which I found an explanation in Michael Polanyi's writings. While I delved into the letters with the help of contextualisation by musicologists, it often felt that the personal tone made me a contemporary of Claudio Monteverdi or vice versa. If we strip that phenomenon of its projection, then still knowledge is communicated, easily bridging four centuries in time. A heuristic feeling came up that this contact over centuries could be realised in a theatrical performance. The knowledge would no longer just sound in the head of a reader but be staged and simultaneously shared with many.

To me, it was obvious that all this research should be compiled into one large PhD project of artistic research, together with a practical realisation in the shape of an opera, for which a creative team of composers was already standing by.

This proposal was accepted in the DocArtes program, although doubts were expressed at its start about the feasibility of the opera project.

The research was clearly in the realm of epistemology and historical performance practice. However, the practical side of the case study—The Tacit Knowledge of Claudio Monteverdi—enlarged the spectrum of inquiry considerably by connecting modern composition to Monteverdi’s modernities at the beginning of the 17th century.

The practitioner Monteverdi

With some simplification, tacit knowledge belongs to the practitioner, and explicit knowledge is the domain of the theorist. In the chapter Dichiaratione, I have demonstrated that Monteverdi and later also his brother used this opposition willingly to disarm their opponent Artusi. These examples are indicative of the composer’s view of his own profession, particularly concerning performance.

Music historians have always been rather silent about Monteverdi as a performer (see chapter The Narrative), but this is crucial to understanding his position in the innovations they granted him. This lack of attention is mostly due to himself because, from the beginning, he avoided, with one exception, any reference to being a singer and a viol player (See the beginning of the chapter Contexts). It is not difficult to imagine him actively taking part in singing his madrigals at the beginning of his career at the Gonzaga court.

For his viol playing, this is different. There is one very explicit reference to him as a virtuoso on the viola bastarda, which, in the context of the Dichiaratione, is even more meaningful. The fact that even after his Orfeo, he is said to play the viola bastarda in court regularly tells me that he was not just showing off with fast improvisations but that he did wonderful things in improvised counterpoint as well (see The Narrative-Banchieri). This last clue indicates that he mastered an art that depended on reflexes from profoundly interiorised practical knowledge. More study is needed to reconstruct these particular qualities, for instance, with the help of his many compositions on a basso ostinato. Is their origin in his experience with the ‘contrapunto alla mente sopra il basso’? But his skills as viol player must have created a rich palette of sounds. After all, there must be a reason that his obituary compared him with Orpheus, which says he did not have an equal with the sound of his viol.

Virtually all of Monteverdi's music has a vocal character, even the instrumental parts. This, along with all the other qualities of his music, characterises him as a composer-singer. The fact that he needed to know for what singer he was writing when asked to send music from Venice, (see Contexts) so he could give some thought ‘to the appropriate natural voice’ indicates that he was very intimately familiar with the physical peculiarities of human voices. The same goes for his report of an audition, with detailed comments.

In close relation to this are his recommendations for abundant rehearsing for singers. Like actors, singers needed to live (dwell) in their parts before they would be able to fully embody them. Freedom in delivery and sprezzatura was only possible when they had interiorised the full spectrum of what they had to represent, both vocally as in terms of the musical meaning.

Even one madrigal needed severe preparation for the singers, as he wrote, because it was very difficult to sing without first practising. It could not be completely understood at first sight and it would do harm to the composition, to sing it unprepared.

Text

In Monteverdi’s letters, abundant information is given of the kind referred to above. But when he turned to a more personal communication register, I saw many possibilities for using literal sentences for the dialogues in my libretto. I later found out that there are resemblances with ‘Verbatim Theatre’, which became more popular while I was compiling texts for the opera. (see chapter Writing the libretto) The principle is the same, which means the effort to stay as close as possible to the source and so obtain a certain truthfulness. This attempt at authenticity pays off when consistency is required in staging a subject that depends greatly on believable wordings. It has a tacit function as well if we consider the text to be a musical score that demands meticulous reproduction of the subtext’s intentions.

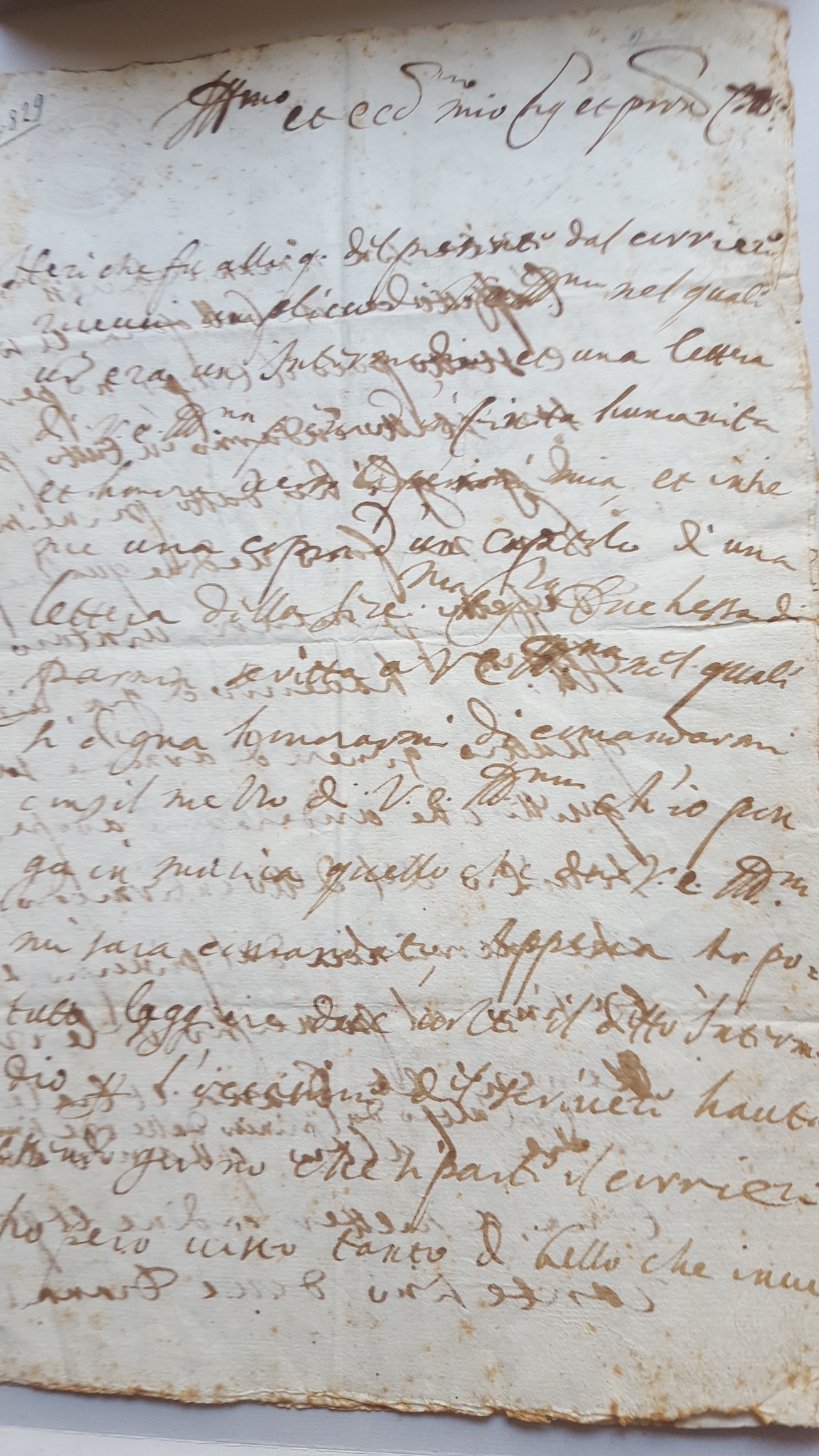

Because Monteverdi actually wrote down his words, voicing them is primarily an embodiment of the thoughts and feelings of that moment. Graphology might have added an extra layer of reading, but it has not been attempted in the context of this research.

The printed sources such as the ‘Lettera ai studiosi lettori’ and the ‘Dichiaratione’ (see chapter) do not have the immediacy of the letters. Still, they have, on the other hand, the extra dimension of an ‘audience’ that is addressed by the authors. It is, so to speak, already a step in the direction of staging.

Monteverdi is not the only one present in the staging through his letters; Eleonora de Medici’s words in the scene where Caterina Martinelli dies are all taken from her personal correspondence.

There are four scenes of theatre within a theatre. Literally so, with the text of Andreini's dialogue between Momo and Verità in Act III. The other scenes are ‘opera in opera’: Orfeo, Dafne and Arianna, which all have their subliminal layers of connotations.

Characters

The layers in the libretto are determined by the construction of the characters.

There are four basic layers in each of the protagonists:

- Historical

- Mythological

- Allegorical

- Theatrical

These layers constantly cross each other in a fluid way, similar to the graphical image of the pyramid in the chapter about Polanyi.

The only character who does not have the extra layers is Monteverdi, who is only historical.

However, a possible interpretation of the whole narrative is that all the figures are just his projections and part of his personality. In that case, the allegories are only his own subconscious psychological properties.

Claudio Monteverdi

Piacere (Caterina Martinelli, Eurydice, Amor, Dafne)

Potere (Eleonora de Medici)

Verità (Virginia Ramponi Andreini, Florinda, Arianna)

Vanità (Francesco Rasi, Orfeo, Apollo, Teseo)

Ragione (Daedalus, Giovanni Maria Artusi, Ottavio Rinuccini)

Comici Fedeli

Just like the historical situation of the artistic processes La Tragedia di Claudio M is reflecting on, the role of the Commedia dell’arte troupe is essential in the theatrical transformation. They represent the embodiment of all aspects of the drama, even to the point that the prima donna of the group, La Florinda, performs the tragic highlight of the opera, the Lamento d’Arianna. In all the historical comments this scene is praised by contemporaries as a revelation.

In our opera, the Comici are constantly present and create a continuum of action, except for the scene of the Lamento, when they disappear for the total time of Arianna’s monologue. Three times, they have the stage for themselves and play a kind of intermezzi, which are part of the total dramatic structure. In the Idropica they fulfill the historical duty of presenting their play. The pantomime before the start of Dafne is an introduction to the lightness of that opera and makes a cesura with the heavy circumstances surrounding Monteverdi.

The most classical Commedia dell’arte is the scene of Zanni and Arlecchino with the laural tree that is left over after carnival and embodied by the ill Caterina. The burlesque performance by the two comici enhances the contrast with Caterina's dramatic situation. When a doctor arrives, he appears to be also a comedian, and the tension culminates into a collapse of the hilarious and elevation of the tragic. Suddenly, there is the fragility of human existence about which we did read from a distance, but now suddenly participate in the magical concentration of the theatre.

The Music

The five composers who wrote the new music for La Tragedia di Clauio M can be seen as operating in a 21st-century equivalent of the explorative framework of the Camerata dei Bardi. They worked on the project for several years and had in the centre of them a radical theorist-composer, Cornelis de Bondt, who is not afraid to take an isolated position within the cultural community if following his ideals should oblige him.

Many discussions have been held to arrive at an alignment with Monteverdi's performance principles, as I wished for this research project.

Instrumentation with just historical instruments was one condition. Initially, attempts were made to include more improvisation, but this delayed too much the completion of reliable musical planning that served the narrative. The only free improvisation was done by the experienced jazz double bass player Yussif Barakat. He accompanied the Dafne pantomime of the Comici Fedeli in Act II.

Crucial was our mission to develop a consistent version of 21st-century parlar cantando.

It took a long time and many trials before each composer contributed with their own solutions, thanks to the fact that every vocalist had a separate composer exclusively writing for them. Automatically, this resulted in contrasting allegorical characters endorsed by the connection of attributed instrumentation. All allegories had their own symbolic instruments.

The stylistic and dramatic coherence on the level of music was composed by Cornelis de Bondt. He designed a two-layer continuum by a thematic formel that was distilled out of the Lamento d’Arianna with the help of his personal MS-Dos composition program. This had the function of a cantus firmus, a musical backbone for the entire opera, playing a leading role inthe apotheosis at the end of the opera.

The other layer he called the ‘Fate layer’ which interrupts now and then the action, as a symbolic reminder of (life) time.

As in the early 17th-century performance, a lot of freedom was granted to the singers and instrumentalists. For the ‘rules of the game’ see the instructions of the score.

The project as a probe

I consider the entire project with all its different components, such as preparative research, discussions by the makers and actors, creative and professional input by composers and performers, stage directions and stage set design, reactions from the audience, etc., the cluster of this all, as an embodied probe stick. (see chapter Episteme)

At the proximal side of this probe are we, living now, and every collective member with their own epistemic archive. On the other (distal) side of the probe, which bridges more than 400 years, there is the living Monteverdi, embedded in his time, social and cultural environment, and complete with all his knowledge, transforming because knowing is a process that happens to him.

This probe stick is a sophisticated feeler, not a rigid tool. It continuously morphs and rejuvenates through actions and interactions and by letting go of ballast. It regularly touches the other side, and signals come our way, but because the distance is vast, we might just think that we know what we feel. It just as well could be another bias, coloring perception.

For the solidity of this probe, which can be bent into an interpretative frame, I have designed a few conditions. The narrative should stay as close as possible to the factual reality as we know it (thanks to a lot of hard work by many musicologists and performing artists). Every decision should refer to this backbone. The last line of Monteverdi’s ‘lettera’ is guiding not just for composers but for all the makers and performers.

...Il moderno Compositore fabrica sopra li fondamenti della verità.