The role of knowledge in playing music from the past.

The origin of all knowledge is tacit, and experience is its fundament. In that sense, one could say that implicit knowledge is basic, and all other appearances of knowledge are just reductions or modifications of this larger whole. This overarching property is inherent in art. It counts for final artistic products as much as for their practical beginnings.

Remarkably, education in the artistic field does not sufficiently recognise this fact or organise the approach to knowledge accordingly.

Trained as a musicologist and a performer of historical instruments (mainly viola da gamba), my relation with knowledge was the menu of daily life throughout my professional career. This relationship had many angles, and it was not always easy to give informative knowledge an appropriate place and function to make it, first of all, feeding my musical practice.

Historical performance practice defines itself as a research-based approach to music of the past. This means that sources such as treatises, scores, playing methods, iconography and organology largely dominated the practical routines. In my case, the imperative of factual knowledge over other aspects of music-making often caused me to experience music as speaking somewhat indirectly to or through me. With hindsight, the large quantity of explicit knowledge was taking up a lot of space that was actually destined for other qualities as a player.

The increase in this knowledge had two different consequences, which are natural phenomena. Parallel to learning from the unknown to knowing a gradually expanding amount of facts and details, there was an increasing awareness of what was still to be learned. The more one knows the better one sees what is not (yet) known and what probably will never be known.

On the other hand, the previously unknown became familiar and embedded in (sub)conscious practical application. Things started to speak for themselves. This latter trend is part of a collective movement of historical performance practices, which expanded considerably by the massive exchange of knowledge in the field since the early 1970s.

Over the decades, the movement developed certain implicit rules concerning historical repertoires, leading to an inevitable standardisation. A tacit agreement on how to realise extant scores based on rules distilled from the sources had become a recognisable practice.

These standards were challenged based on newly acquired knowledge or views with alternative motivations. The objections to the beliefs, integrated into the ever more successful historical performance practices, eventually culminated in the so-called ‘Early Music debate.’

The debate took place in the 1980s. There was an antecedent by Theodor Adorno, which was followed up by Laurence Dreyfus' article Early Music defended against its devotees.

The best-known and most extensive contributor was Richard Taruskin, who, in his own words, 'debunked' the authenticity claim of the Early Music Movement in Text and Act and other publications. Very substantial in the debate were the articles and books by authors like Joseph Kerman, Nikolaus Harnoncourt and (looking back on the 1980s) Charles Rosen.

The debate mainly concentrated on how believable the claims were that the approach of the Early Music Movement represented the original intentions and experiences of the composers of some centuries ago. The claim of ‘authenticity’, though not directly made by the leading performers in the field, was used by record labels and other publicity channels. Ten years after the launch of Early Music, its new editor, Nicholas Kenyon, organised a conference on the topic of authenticity, collecting all the high-profile contributions in his standard work about authenticity in historical performances. In the discussion, the philological scrutiny of the historical performers was confronted with their tendencies to subconsciously project contemporary aesthetics and taste onto the music of the past. The opponents did not challenge the application of knowledge but the omission of including the unknown within the larger picture of artistic valuation. The scrutiny of historical facts needed to be balanced by scientific or epistemological rigour. Instead, a tacit agreement on how to perform guaranteed a lively conviviality and conviction.

Crucial in this opposition against these grades of authenticity is dealing with the ephemeral quality of music that prevents reconstruction. All the knowledge that died with the composers, musicians and instrument makers was and will remain forever tacit. Nevertheless, as with all history, musicians who play the music of the past in some way will have to relate to this dimension.

Wilhelm Dilthey’s axioma ‘Leben versteht Leben’ covers the idea that ‘living life is capable of re-living the life that passed away.’ Central in that process is the carrier of information, the so-called dead ‘Geistiges Objekt’ or intellectual content. The temporarily frozen part of it can be regained through technologies such as scripture or - as in our case - music notation, iconography and musical instruments.

The content of this presumed Sleeping Beauty is subjected to a plethora of interpretations, guided - as Hans Georg Gadamer stated - mainly by the dialogue of every individual interpreter with the text. As a result, we talk of ‘plural authenticities,’ where every version has its authentic meaning instead of one ideal reading. In all this, the author of the intellectual content is simultaneously present and absent, thus causing this polysemic dimension to the preserved work of art. Chasing the original intention of the dead composer is frustrated by a perpetual escape from the ideal content, while its pursuit remains an illusory but inevitable necessity. So, the lost paradise is not behind us but travelling with us in a kind of parallactic movement. Like the moon seen from a driving car on the highway.

The proximal and the distal

The Early Music movement of the 20th century was not the first to bring music and theatre from a distant past back to life.

In the second half of the 16th century, a small group of humanists studied the possibilities of reviving ancient Greek musical drama. A key figure at its beginning was the lutenist and music theorist Vincenzo Galilei, who was inspired by the findings and ideas of his friend Girolamo Mei. This humanistic historian wrote a treatise on the subject De modis musicis antiquorum. The text was never published, but many of his ideas and findings contributed to Galilei's Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna from 1581.

Their work formed the foundation for the Florentine academy, known as the ‘Camerata dei Bardi’ (named after their leader, Count Giovanni Bardi.) This group of poets, composers, theorists and intellectuals discussed the arts and shared an interest in Antiquity. With all the information that Girolamo Mei (consulting Boethius) and later also Galilei brought into the group, they managed to (re)construct a kind of vocal music completely driven by text. They created a way of performing soloistic recitation with slender accompaniment free from the polyphonic structures, much later indicated as the monodic style, then known as the stile recitativo. Galilei describes his conviction (after studying Aristotle's Poetics) that all Greek tragedy and comedy was sung. A practice that was taken over by, as he wrote, I latini (the Romans).

What strikes me is the effort Galilei and some others took to decipher and interpret the original Greek notation, understand their tuning systems, and understand their tonal systems, which consisted of modes characterised by explicit connotations. Apparently, these studies also helped Galilei rethink harmony and increase the use of dissonance in his own harmonic spectrum.

It is specifically noticeable that within a general interest in the arts of Antiquity during the preceding two centuries, very detailed studies of a chain of music theorists (Pythagoras, Aristotle, Boethius, Guido of Arezzo) helped the Camerata dei Bardi to achieve their own rinascita of the antique theatre’s sound.

Knowledge older than 1500 years and handed over in descriptions and codified melodies found its way into the treatises of, above all, Vincenzo Galilei. This knowledge was thus connected with, as well as opposed to, the music theory of the mid-16th century, dominated by the standards of Gioseffo Zarlino. From all the research, discussions, and experiments, a coherent new practice grew, successfully represented by Giulio Caccini and Jacopo Peri. They were the singers of the Camerata who first came with results that found acclaim as a new way of performing music drama in a sung-spoken way.

The most valued achievement in the new style around the time this novelty was expanding, the first decade of the 17th century, was Claudio Monteverdi's Lamento d'Arianna. Even his competitor Marco da Gagliano confirmed that this composer wrote such an exquisite aria that one could truly affirm that he renewed the value of the music of the antiques.

Monteverdi did not share the reconstruction ideal of the Florentine intelligentsia. As he wrote to Doni in 1634, he had taken notice of Galilei's treatise some twenty years earlier and saw the little known about the practice of the ancient Greeks. It was dear to him to have seen it as he wrote to Doni, but he also realized that the old notation was so different from that of his own times that he did not even try to understand them, being sure that they would remain obscure and he would be lost in the practice of the ancients.

Monteverdi's background was that of a music practitioner rather than an intellectual environment such as the Florentine Camerata. Even though he published his first compositions as a 15-year apprentice of Marc'Antonio Ingegnieri, this primarily showed the knowledge of an apprentice developing into a craftsman. His more creative experiments most likely found their way into playing viola bastarda, which was an art of improvisation. The fact that Vincenzo Gonzaga accepted him as a court musician based on these skills indicates that he was an exceptional and, for his age, very accomplished instrumentalist and singer.

From the letter to Doni cited above, we can conclude that Monteverdi considered himself, also with hindsight, primarily a practitioner who would approach such subjects physically, mentally and artistically from the proximity of his own experience.

Polanyi suggested that this kind of scientific or artistic exploration should be seen as an act of probing with the help of a tool.

As an example, he chose the stick of a blind person that helps to avoid collisions with objects or stepping in holes on the way. The stick-holder explores or feels his/her way from what is nearest (in anatomical terms, the proximal) to what is far, in this case, at the end of the stick (the distal). The stick is an extension of the arm/body that feels its way into the unknown and interprets the vibrations and resistances encountered. So, the familiar (the known) is in direct contact with the unknown and by concentrating one's attention and awareness on this bi-directional process of exploration, one dwells temporarily in a circular motion of growing knowledge, which is personal. This indwelling is conditional to gain transformative growth from the whole operation.

This theoretical model's relation to Claudio Monteverdi is obvious here. For a violist or any other player of bowed instruments, the process of learning and performing is similar to the probestick. One feels through the bow, the way into the sound by connecting feedback of resistances with the musical language of bodily actions.

The trajectory in such an exploration is predominantly subconscious and not controlled by the mind. It is a comprehensive physical (neurological) process in which memory plays an independent but crucial role. The knowledge obtained in such a way is mostly subliminal and cannot be articulated in subdivided particulars without diminishing its quality or reducing its truthful compass. Polanyi baptised this knowledge, therefore, as tacit knowing. He saw knowledge always as a process connected to a person. It should not be identified as something fixed.

The interpretative framework

The trajectory in such an exploration is predominantly subconscious and not controlled by the mind. It is a comprehensive physical (neurological) process in which memory plays an independent but crucial role. The knowledge obtained in such a way is mostly subliminal and cannot be articulated in subdivided particulars without diminishing its quality or reducing its truthful compass. Polanyi baptised this knowledge, therefore, as tacit knowing. He saw knowledge, moreover, always as a process connected to a person. It should thus not be identified as something fixed.

For the Camerata dei Bardi, a collective interpretative framework served as a metaphorical probestick. As stated above, this framework consisted of coherent shared beliefs and explicit knowledge about ancient Greek music theory and the vast repertoire of literature. In addition, other interpretative frameworks from more recent authors, such as Boethius or Guido of Arezzo, extended the proximity of the 'stick' in a telescopic way towards the very remote past. A recontextualisation refined the images of the lost practice at the distal end through practical experiments and a search of the proximal side. The indwelling of the group made them contemporary with the cultural field they studied, and at the same time, by projections, they subconsciously morphed that same field to fit the ideals of their present.

According to Polanyi, committing oneself entirely to this process of probing investigation is conditional on its credibility and success. He sees this principle for science as well as (emphatically) for the arts.

"No one can know universal intellectual standards except by acknowledging their jurisdiction over himself as part of the terms on which he holds himself responsible for the pursuit of his mental efforts."

This means that in the case of the Camerata dei Bardi, we are not dealing with a subjective concoction from a collective endeavour. Every individual contribution was submitted in confidence, from a personal passion to the agreed intellectual standards of the group based on historical and artistic fundaments.

Through this framework of commitment, a self-regulating coherence emerged, leading to the growing proximity of the hidden truth of a new style of music drama. The heuristic moments in this research depended on responsible choices of actions, which (as Polanyi describes it) 'excluded randomness or egocentric arbitrariness.'

If we consider a new vocal style as the stile recitativo, as new knowledge, Polanyi's observations concerning this chapter are very appropriate in our case:

The implications of new knowledge can never be known at its birth. For it speaks of something real, and to attribute reality to something is to express the belief that its presence will yet show up in an indefinite number of unpredictable ways."

If we draw this picture much broader, we can say that there was an inevitable line from the first tentative attempts to combine speaking and singing until, finally, the mature appearance of opera as a new medium.

Vincenzo Galilei's research was the most scientific contribution to the Camerata. He found the arguments above all in Aristotle's work. He 'coloured' the information, however, by freely interpreting some statements about the fact that Greek tragedy was actually sung and not spoken.

In his Dialogo, this conclusion is based on paragraphs 6 and 15 of book XIX in Aristotle's Problemata (Problems Connected With Music) and on the Poetics chapter VI, which states that some texts were spoken and others 'rendered with the aid of song' (see above). Galilei admits this last contradiction, blaming Aristotle's memory. Did he subconsciously want to follow his own track to see the confirmation of fully sung tragedy?

Indeed, the Greek term for mixing speaking and singing connects with tragedy in the mentioned fragments of the Problemata. The translation of the word parakatalogí (παρακαταλογὴ) is by scholars generally accepted as recitative/reciting. So, for Galilei, this passage in the book dedicated to music was a key to his conviction about sung Tragedy.

(Aristotle, Problems, XIX, 6.) Why is recitative in songs tragic? Is it because of the contrast? The contrast evokes emotions and is found in extreme calamity or grief, while uniformity is less mournful.

Mimesis

Even more relevant than the role of song in Tragedy are Galilei's searches for indications of the role of imitation within acting. As we saw above in the quoted passage of the Poetica, Aristotle underlines the aspect of imitation in acting, by and in language, which enhances the emotional impact. In paragraph 15 mentioned above, he explicitly sketches the work of the specialised actor (ἀγωνιστῶν) and the performance of the nomoi (melodic patterns, songs) who contrasted by their length with the choral strophes:

(Aristotle, Problems, XIX, 15)

Is it because nomoi were for professional actors, who, being already able to perform imitations and exert themselves for a sustained period, their song became long and multiform? Like the words, then, the melodies too, followed the imitation in being continually varied. For it was more necessary to imitate by means of the melody than by means of the words.

The protagonists had a fair amount of musical freedom to use their palette of emotional imitations translated into musical expression. The chorus could not because "it is easier for one person to execute a lot of modulations than it is for many." The conclusion is that the hypocritès (the actor) is an agonistes (professional virtuoso) and a mimetes (imitator).

Michael Polanyi discusses mimesis in another context, which is nevertheless related because it deals with the transmission of knowledge by imitation. This tacit learning of knowing how to do something was first described after observations of animal behaviour. Not the "blind parrot-like imitation, but a genuine transmission of an intellectual performance from one animal to the other; a real communication of knowledge on the inarticulate level."

Polanyi points out that all arts are learned in this way of intelligently imitating and that there is a condition for the learner to place his confidence in the master. This principle is not limited to the master-apprentice relationship. The actor can imitate a person who is a model for a role or character by the same intelligent observation. In turn, the craft of the imitator can be imitated to learn more about expression for other purposes.

Vincenzo Galilei saw this strategy of learning by imitation as the ultimate chance to get closer to a genuine text expression in music. He advised his readers interested in the rhetorical style of the ancient Greeks to observe the comedia dell'arte actors (i Zanni) of their present-day tragedies and comedies.

Quando per lor diporto vanno alle Tragedie & Comedie, che recitano i Zanni, lascino alcuna volta da parte le immoderate risa;

& in lor vece osservino di gratia in qual maniera parla, con qual voce circa l'acutezza & gravità, con che quantità di suono, con qual sorte d'accenti & di gesti, come profferire quanto alla velocità & tardità del moto, l'uno con l'altro quieto gentilhuomo

attendino un poco la differenza che occorre tra tutte quelle cose,

quando uno di essi parla con un suo servo, overo l'uno con l'altro di questi; considerino quando ciò accade al Principe discorrendo con un suo suddito & vassallo

quando al supplicante nel raccomandarsi; come ciò faccia l'infuriato, ò concitato;

come la donna maritata; come la fanciulla; come il semplice putto;

come l'astuta meretrice; come l'innamorato nel parlare con la sua amata mentre cerca disporla alle sue voglie;

come quelli che si lamenta; come quelli che grida; come il timoroso;

e come quelli che esulta d'allegrezza,

da quali diversi accidenti, essendo da essi con attentione avvertiti & con diligenza essaminati, potranno pigliar norma di quell oche convenga per l'espressione di qual sivoglia altro concetto che venire gli potesse tra mano.

With these examples, Galilei pointed to direct imitation through intelligent observation. In this example, the intelligence is not reflective but sensitive to goal-directed behaviour. In Polanyi's terminology, the observer is advised to dwell in the mind of the performers during the action. Four hundred years after Galilei, Polanyi correctly described such processes as a tacit functioning within learning. A transmission of knowledge occurred under the radar of our conscious mind. In art, the advantage of such a way of learning is that the wealth of details, nuances, refinements, curiosities, inexplicabilities, etc., next to the undividable qualia aspects, 'the suchness' of relevant items, is not sacrificed to inevitable processes of reduction or compression. Explicitation would produce an effect of impoverishment of meaning compared to the original expression remaining embedded in its totality.

Half a century after Polanyi's conclusions, neuroscience succeeded in refining such observations by directly measuring brain activities during primates' learning. In his book The Neuroscience of Human Relationships, Louis Cozolino dedicates a chapter to this fundamental principle of social coherence facilitated by so-called mirror neurons.

"The microsensors revealed that neurons in the premotor areas of the frontal lobes fire when another primate is observed engaging in a specific behaviour. [....] Because these neurons fire both when observing and performing a particular action, they have been dubbed mirror neurons." [...]

"Mirror neurons lie at the crossroads of the processing of inner and outer experience. [...]

It is because of their priviliged position that mirror neurons are able to bridge observation and action."

Cozolino's research is relevant here because he also studied the relation between words and gestures. These are linked even to the point that our tongue muscles are activated by listening to speech. So, the action of speech of the sender, as well as facial expressions and gestures, result in reflexive activation of motor systems in the observer.

Galilei encouraged composers and musicians to observe the actors in action in order to follow their performances as musical gestures, which could be captured in the shape of recitatives. Crucial is the immediacy of the process. The fact that no analysis comes in between what happens and how it is reflected in the receiver makes the artistic outcome experienced true. It is the dramaturgical equivalent of the verisimilitude of the visual arts.

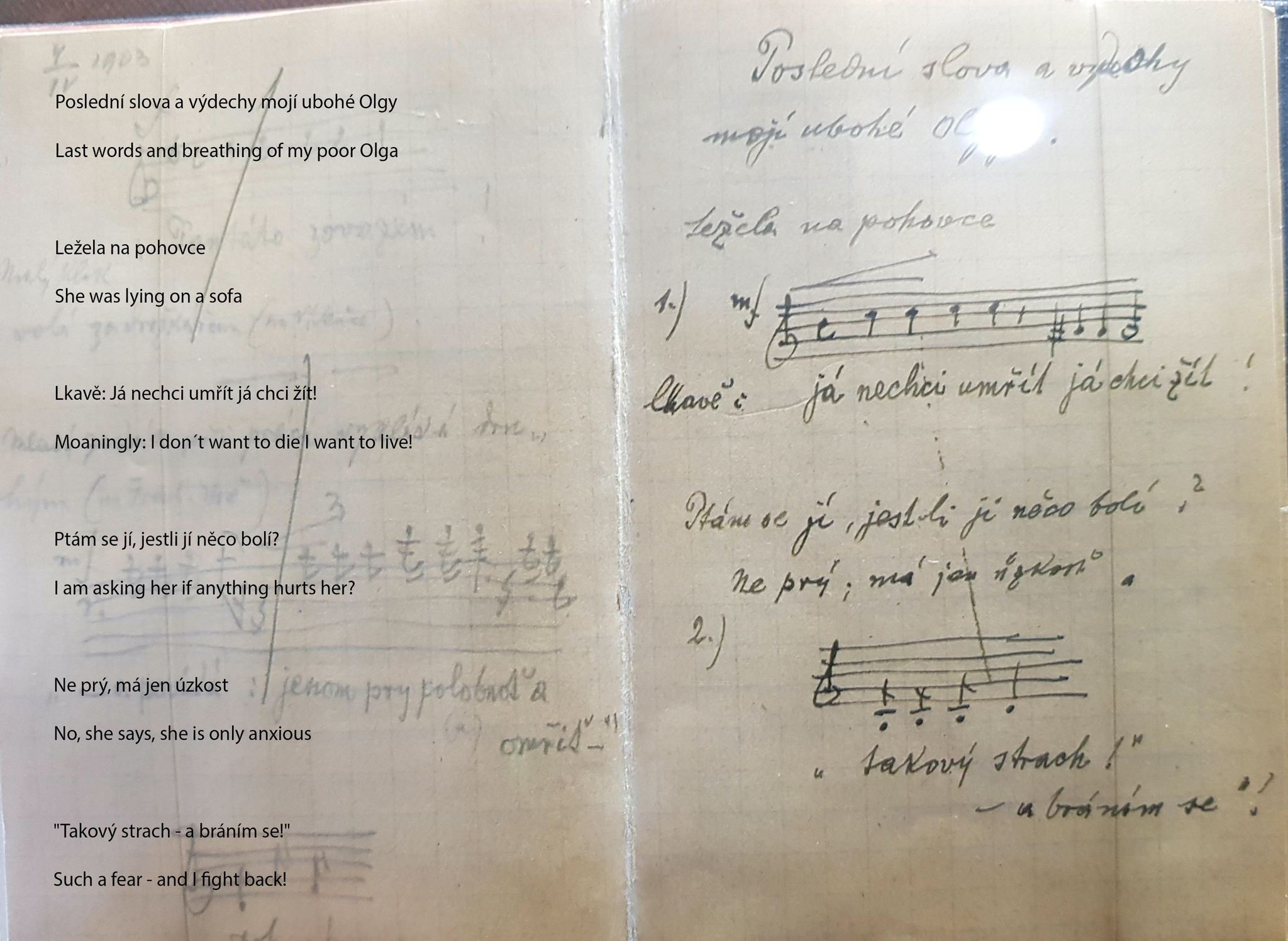

A similar way of working had become second nature to one of the great opera composers of the 20th century, Leoš Janáček. He used to write down conversations or spoken language around him directly in music notation in a little notebook. He wanted to catch the musical dimension of his mother tongue (!) at its most lively manifestations. Ironically, this habit was so dominant that even at the deathbed of his daughter Olga, he wrote down the scene in that notebook. Turning what was truly happening into a dramatised scene, like an artist making a drawing of the deathbed of a family member.

Janáček's method mirrors Vincenzo Galilei's ideal when transferring spoken word to music. Galilei mostly paid attention to the precise characterisation of the person represented by the ancient singers. He summarizes the recommended observations above and puts them into practice, translating them into musical action of tone, accents and gestures, volume, and rhythm.

Nel cantare l'antico Musico qual si voglia Poema, essaminava prima diligentissimamente la qualità della persona che parlava, l'età, il sesso, con chi, & quello che per tal mezzo cercava operare; i quali concetti vestiti prima dal Poeta di scelte parole à bisogno tale opportune, gli esprimeva poscia il Musico in quel Tuono, con quelli accenti, & gesti, con quella quantità, & qualità di suono, & con quel rithmo che conveniva in quell'attione à tal personaggio.

Galilei was the first of the Camerata Bardi, who realized a composition in the new monodic style, which he sang himself. There is a testimony of Giovanni Bardi's son Pietro in a letter from 1634 to Giovanni Battista Doni that he sang with a clear tenor voice, accompanied by a consort of viols, his Lamento di Conte Ugolino after Dante's Inferno. Apart from the good voice, he apparently sang intelligibly, and although the music lovers liked it, the performance created envy among his colleagues. This stile recitativo was a discovery for Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini, but they found 'too much antiquity and roughness' in Galilei's approach. According to Pietro Bardi the two singers 'softened the style and made it suitable to arouse affects by it, which were seldom heard.'

Dwelling in, breaking out

For Galilei, probing by his interpretative framework resulted in an immersion in his field of study, ancient Greek music. To see it through Polanyi's eyes, we would say that his contemplation brought Galilei from an observer of experiences into a person absorbed by their inherent qualities. "The impersonality of intense contemplation," as Polanyi states, "consists in a complete participation of the person in that which he contemplates. And not in his complete detachment from it, as would be the case in an ideally objective observation."

Galilei's lamento was more an explorative experiment than the work of his younger colleagues. Hence the roughness of his findings and the slightly fanatic endeavour to evoke the antique original in an uncompromised appearance by artistically breaking out of the habitual frames.

Quite deliberately so, because he departed from a hunch (a tacit fore-knowledge) of what the original Greek music must have been like. However, he knew he could only approach it instead of rediscovering its original appearance. His priority was to break out of the expressive limitations of polyphony.

In a key chapter of Personal Knowledge, “Dwelling In and Breaking Out,” Polanyi compares artistic innovations with the chain of upheavals in scientific development. Though mainly taking place in the tacit dimension, he states that "new movements of art include a re-appreciation of their ancestry and a corresponding shift in the valuation of all other artistic achievements of the past." Therefore, Polanyi's definition of the appreciation of art is not verification as in measurable natural sciences but validation.

The attribution of value instead of verification to the way the revival of ancient music is appreciated creates a paradoxical layer to Polanyi’s statement, which Charles Rosen ironically refers to as the “Shock of the Old.” In the Early Music debate described above, ethical questions determined a large part of the discussions. If we classify historical performances as ‘new movement of art’ the re-appreciation of earlier performances is obvious. They are mostly considered ‘outdated’ when measured to standards of historical evidence but can still be valued based on other parameters. These aspects that prevail above the historical informed are most of the time related to the tacit knowledge of performers and their traditions.

The ethical card was not only drawn by the 20th-century Early Music Movement. The idealism that motivated Galilei’s ardent research and experimentation also carried a component of projection.

Pietro Bardi stressed the support Galilei received from his father, Count Giovanni Bardi, who specialised highly in the same material as his companion. The Count's help was needed and much appreciated as we read in the dedication of Galilei's Dialogo, printed in 1581. From that book, we see Galilei's wider context and belief in experiments as a condition for proper research. He had found the right companion in his sponsor because apart from investing financially, Count de' Bardi 'toiled for entire nights for such a noble discovery.' The consequence of choosing that path is described by Pietro Bardi as an arduous undertaking that was then often considered ridiculous.

New artistic phenomena have been ridiculed very often, certainly since the early modern times. In this case, it is remarkable that the values of the past were taken as a starting point, and Galilei determined he needed to go against what he considered the delusions of his days and restore values.

In his enthusiasm, he even attributes words to Aristotle that are not found literally in the philosopher’s texts.

& parimente Aristotile: dicendo egli, che quella musica la quale non serve al costume dell'animo, è veramente la disprezzarsi. Dialogo, p.84

(…and likewise, Aristotle says that music which does not serve the custom of the soul is truly to be despised.)

Galilei was determined to go against the fashions of his days and made a moral appeal to his contemporaries to seek the higher values of their art instead of satisfying the senses with entertaining novelties.

“Tra i Musici antichi di pregio, fu sempre grandemente reputata la severità, & la curiosità avvilita; dove per il contrario quelli de nostri tempi, hanno senza rispetto alcuno à guisa degli Epicurei, anteposto à ciascun'altra cosa, la novità per diletto del senso;”

(“Among the ancient Musicians of merit, a serving attitude was always greatly esteemed, & curiosity debased; where, on the contrary, those of our time have, without any respect, like the Epicureans, put novelty before everything else for the pleasure of the senses;”)

Even though his experiments were embedded in a movement of avant-garde, he still had to stick his neck out with something that initially risked being misunderstood even by his peers. In the history of artistic development, there are many pivotal changes we can point to as moments an artist broke out of an existing structure. Validation was often only possible in the aftermath of the event, and the implications were initially uncertain, as with all appearances of new knowledge.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we see that by playing music from the (remote) past, an infinite quest for more knowledge will be generated after the interiorisation of every discovery. On a large scale, this has been made clear by the Early Music Movement that started in the 1960s. The commitment of that community ended up in a collectively shared ‘personal knowledge’ raising an increasing awareness that the most wanted knowledge would remain forever tacit because it died with its owners. The positive side of this fact has manifested itself as a quest for a ‘lost’ ideal that, in a parallactic movement, travels in time with all the searching artists, thus stimulating creativity.

A parallel can be drawn with a similar movement at the end of the 16th century, the Camerata dei Bardi in Florence. Their efforts to develop music drama based on ancient Greek tragedy were guided by Vincenzo Galilei, who had a visionary approach to reviving vocally recited drama. Understanding these efforts along the lines of Michael Polanyi’s theoretical model of the probe, or in this case, a collective interpretative framework, we have a clear example of a path to the discovery of new knowledge (in this case, the stile recitativo) by dwelling in shared beliefs and explicit theoretical facts of ancient Greek music. Galilei’s probe functioned like a telescope, going from more recent authorities like Guido of Arezzo via Boethius in the Early Middle Ages to Aristotle, whom he considered the main authority in his search.

Indeed, this path would lead to the important discovery of mimesis, a tacit process of learning by imitation, as a guiding principle in creating a vocal style. This would preserve the actor's available tools in representing a dramatic character while singing.

Galilei’s theory about imitation in this context is not only endorsed by Michael Polanyi’s explanations of the 1950s but also confirmed by neuroscientists like Damasio and Cozolino seventy years later.

Monteverdi, who chose the practical way, rejected the intellectual idea of reconstructing Greek tragedy. Nevertheless, he took notice of Galilei’s writings and profited after Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini from the newly developed stile recitativo and, according to his colleagues, led it to a higher level of perfection.

Comparable steps towards an ideal of merging spoken language and song in twentieth-century opera, like those of Leoš Janáček or Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, can be deducted to originate from a similar process of applying their tacit knowledge.