La Tragedia di Claudio M.

(Full Score)

Cornelis de Bondt

Nikos Kokolakis

Cristiano Melli

Ivan Renqvist Babinchak

Renán Zelada

(Orffeus -Edition 180518-01, © 2018)

INDEX

Act III.1, Act III.2, Act III.3

Composing the opera

- Interview with Cornelis de Bondt

- Layers

- Workshop Donatienne Michel-Dansac

Monteverdi project – Cantus Firmus [CdB -21 november 2015]

Introduction

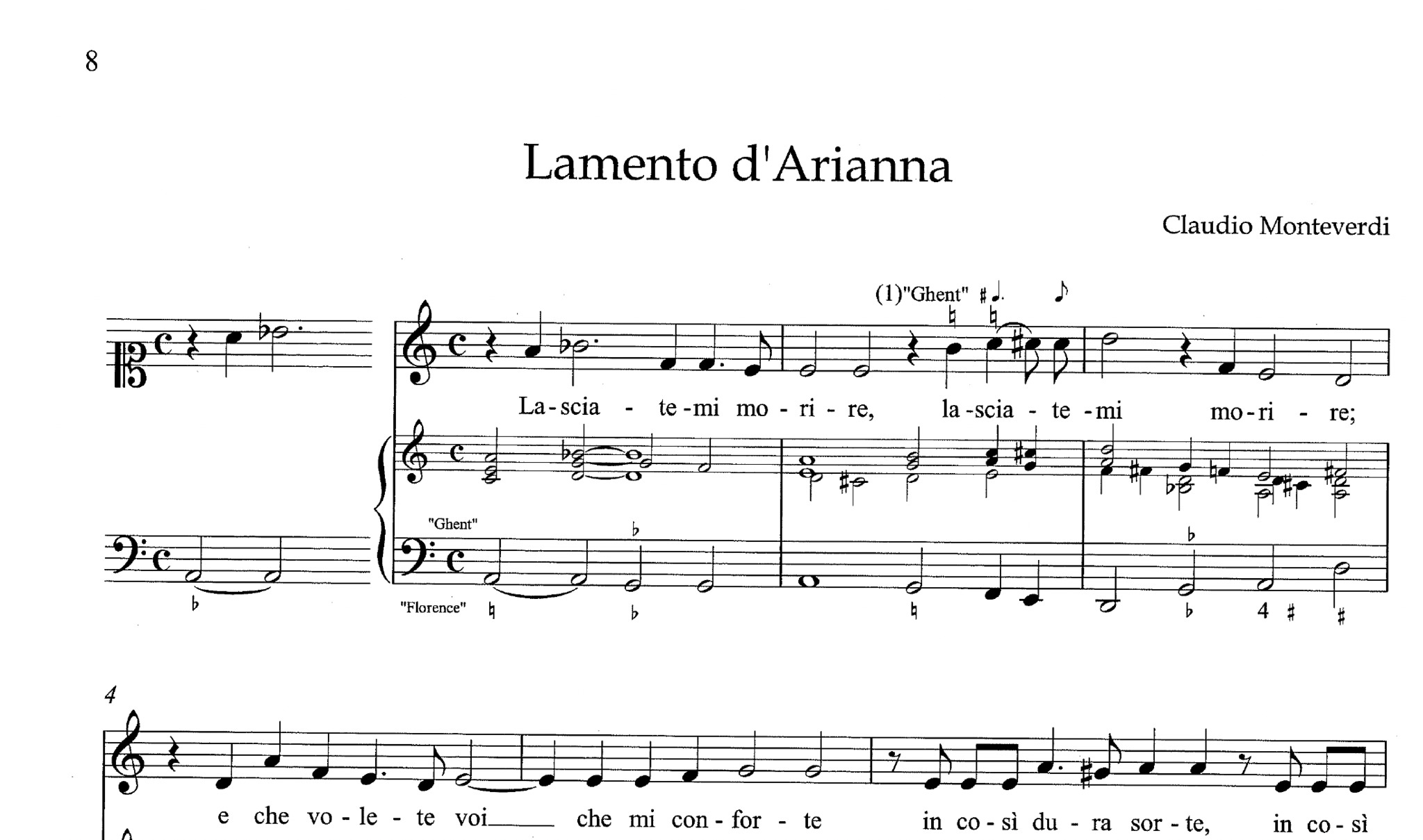

My contribution to the Monteverdi opera will be a layer, which can be understood as a cantus firmus or basso continuo or even a variant of a Stockhausen Formel, on top of which, or against it, can be placed any other form or piece of music. This Cantus Firmus layer [CF] is to be developed collectively, both by composers and musicians. The layer actually is more a principle than a concrete piece of music that can be notated in a score. Like is the case – for whatever reason – with Monteverdi’s Arianna, there will be no score left in the end.

In Opus Deo the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben tries to capture the archaeology of the concept of liturgy or duty. At some point he refers to the Roman rhetorician Quintillian, who made a distinction of two types of art: art that was in actus and art that was in effectus. Art in actus, like dance, has its end in itself; art in effectus, like painting, reaches its end in a concrete object. Music can be generally seen as being in actus, although the phenomenon of a score is in effectus. From the romantic age one can argue music is gradually seen more and more as in effectus, and it took until the times of researching early music practice that the in actus principle became important again.

We can look at music from different perspectives, different layers even, of which some articulate the in actus and others the in effectus. I see my cantus firmus layer as typically in actus. A written out – or quoted – aria, recitative, choral or other music is then in effectus compared to this layer. It is an object that is placed above, underneath or towards it.

Something similar can be stated about the text. Given text, taken from the libretto of Orfeo or Arianna are then in effectus, where a text which is open, maybe even improvised (we never discussed this as far as now) would be in actus.

Cantus firmus layer

In order to get this layer to function well, we need to develop and formulate criteria and music technical tools.

The main principle of the layer is speed. That is mere personal taste. Most contemporary (art) music is slow, because it is more about sound or conceptual exploration and expression than about a linguistic articulation. Probably because we lack the means and tools to do this, without falling back in style and techniques we so desperately have left behind us. So there lies the challenge I seek. Which is a matter of taste, but not only; it is also an inquiry into the techniques and styles we lost somehow.

Every composer, or musician for that matter, can ‘fight’ my layer. We can freeze it, slow it down to –273 Celcius, let it be out of our ears for minutes or longer, but, since it is in actus it cannot be treated like an object, like a ‘section’; even if it seems to be gone it will still be there, as potential energy. Freezing it is loading up the energy, that at some point will have to be released. It is the motor inside the opera, and we can decide to what degree we create a case (Dutch: ‘mantel’) around the machine, so to what extent it is hidden or not.

Criteria

1. Tempo

There will be one fast movement, for instance like 16th notes in mm144 (we have to determine this). This can be recalculated in other tempi. Like sextuplets in mm96 or triplets in mm192. All rhythm will be derived from this. I prefer the cantus firmus [CF] to be based on 2, 3 or 4. For quintuplets and other fashionable numbers I have no talent, and I leave them to my students if they prefer.

2. Rhythm

The basis is a continuous 16th movement. This does not mean it is restricted to this, it simply means the rhythm (of the CF, not of other layers) is derived from this. E.g. if the 16th note is represented by the number 1, then all other numbers can be used.

Example: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 3 4 gives: jjjq jjjq x e x _ iq _ e

When the beat is based on triplet, the 1 represents the triplet 8th note.

3. Rhythmic synchronisation

The players involved in the CF can be in or out of synchronisation. We have to invent how to control the moment of being in or out sync.

4. Mode

The melodic lines of the CF are based on modes. The durations where the modes are valid are to be designed (Harmonic rhythm). A mode can be any series of notes; it can be a conventional major or minor scale, a church mode, but also a free-designed series. The melody always follows the mode stepwise, but when the mode is structured in larger intervals than seconds, obviously greater intervals than seconds will occur.

Like a basso continuo the harmonic rhythm will determine the overall harmony of the other layers. We can find out to what degree, or where the limits of the harmonic liberties are to be found.

5. Melody

NT-FR, NT-TO: The melody for a certain duration can be determined by the cue NT-FR and NT-TO. Note-From gives the starting note, Note-To the goal.

MEL-SHAPE: This type gives the shape or curve of the melody. It can e.g. be linear MEL-SHAPE=LIN; then the melody is just a straight line up or down. It can be like a sinus wave, going gradually up-down-up-down, like e.g. two steps up, one down, two up, etc. MEL-SHAPE=SIN. These types can be refined in many ways. (Like 3 up, 2 down, etc. or more complex and capricious forms.)

Melodic synchronisation: There are two types of sync: in rhythm and in pitch.

6. Instrumentation

The CF can flow from the bass register up to the upper register. This will automatically influence the instrumentation. Instruments can join it when the melody comes in reach of their range. They will disappear when the melody goes beyond it.

Other issues

1. Use of voice

The CF basically takes care of an underlying form, which can support the large form and the vocal lines. For the use of voice – how do we get to a text setting where the music ‘serves’ the text? - we have to develop (partly) separately. We can focus on the CF first, and once we have some idea of how to deal with it, we can bring in text.

2. Ornamentation/diminution

Also for this technique we first need to focus on the CF, because it provides the overall harmonic setting.

3. Text

We have to figure out how to deal with text. On the one hand, there are concrete text fragments that are taken from existing operas. On the other hand, there will be new text. The idea of writing this text in early 17th century Italian verse form is abandoned. The question is now how the new text is written, will there be at some point a fully written out text, or will parts of the text be (semi-) improvised?

Questions and/or problems of the CF to investigate

1. Tempo

Which tempo will be the fundamental tempo, and which tempi are derived from it?

2. MEL-SHAPE

Which types of melodic shapes will we apply?

How do we notate these different types?

How are they cued? Cueing is a separate subject; see below.

3. Sync.

How do we create tools to control the being in- or out-of sync? This counts for both the aspect of rhythm and pitch.

4. Rhyhtm

How do we control and notate the process of slowing down from repeated 16th or speeding up the rhythm towards the repeated 16th?

There are basically two ways of slowing down or speeding up:

- By tempo

- By duration (in a constant tempo). This might be better when other layers are involved so the overall timing is in control.

5. Cueing

How do we organize cueing?

Possible means:

- By the musicians and/or the singers (main characters), either from a musical cue or from position on stage.

- From the text.

Monteverdi – Layers

There are several layers noticeable in our opera-to-be:

· In the libretto: the specific (historical) characters, the allegories, the historical events and the dramatic events.

· In the performance: singers, musicians, actors (commedia dell’arte).

· In the music: historical music (Monteverdi’s Orfeo, madrigals, Lamento’s), Gagliano, Gastoldi; and newly composed music.

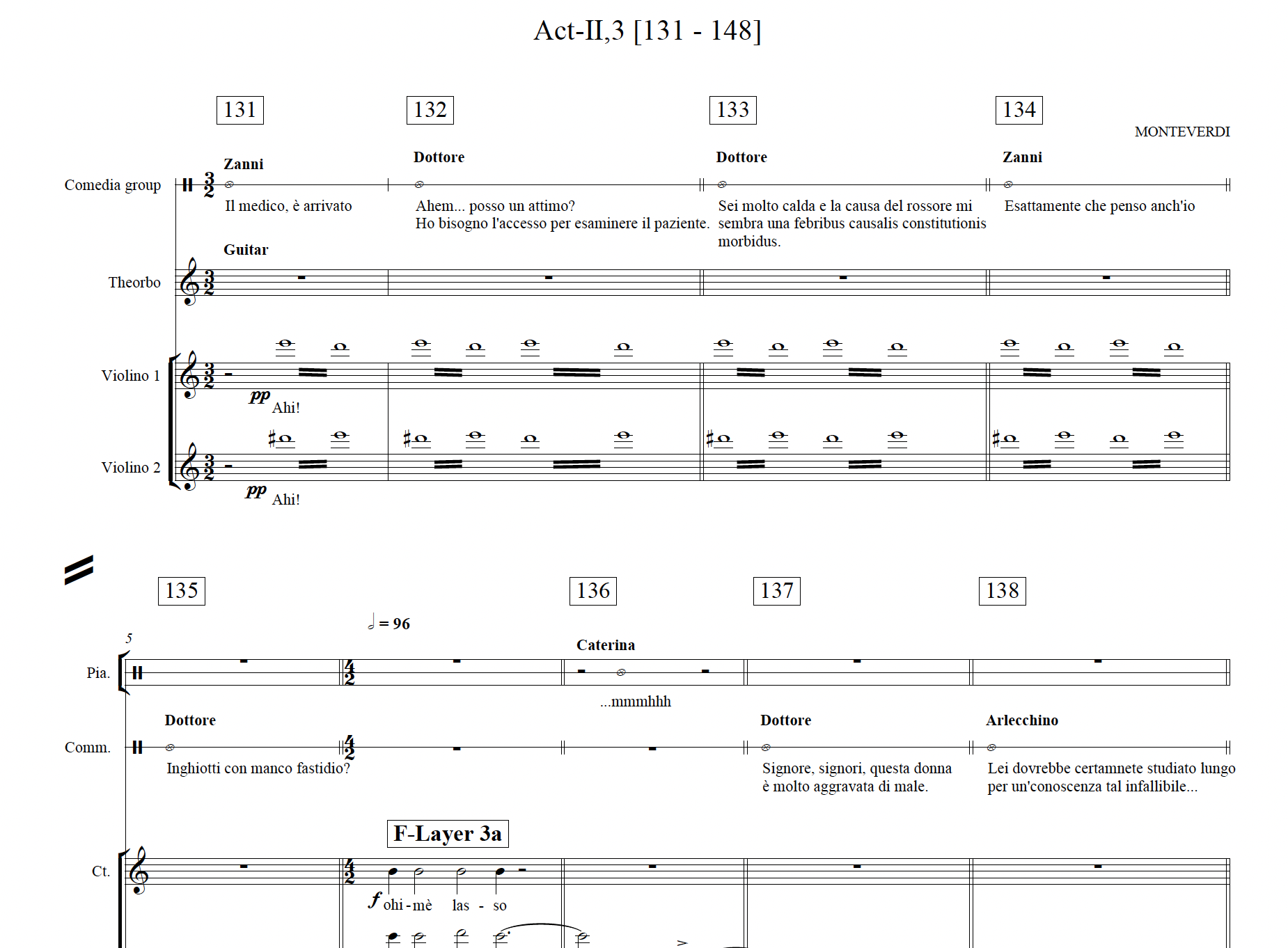

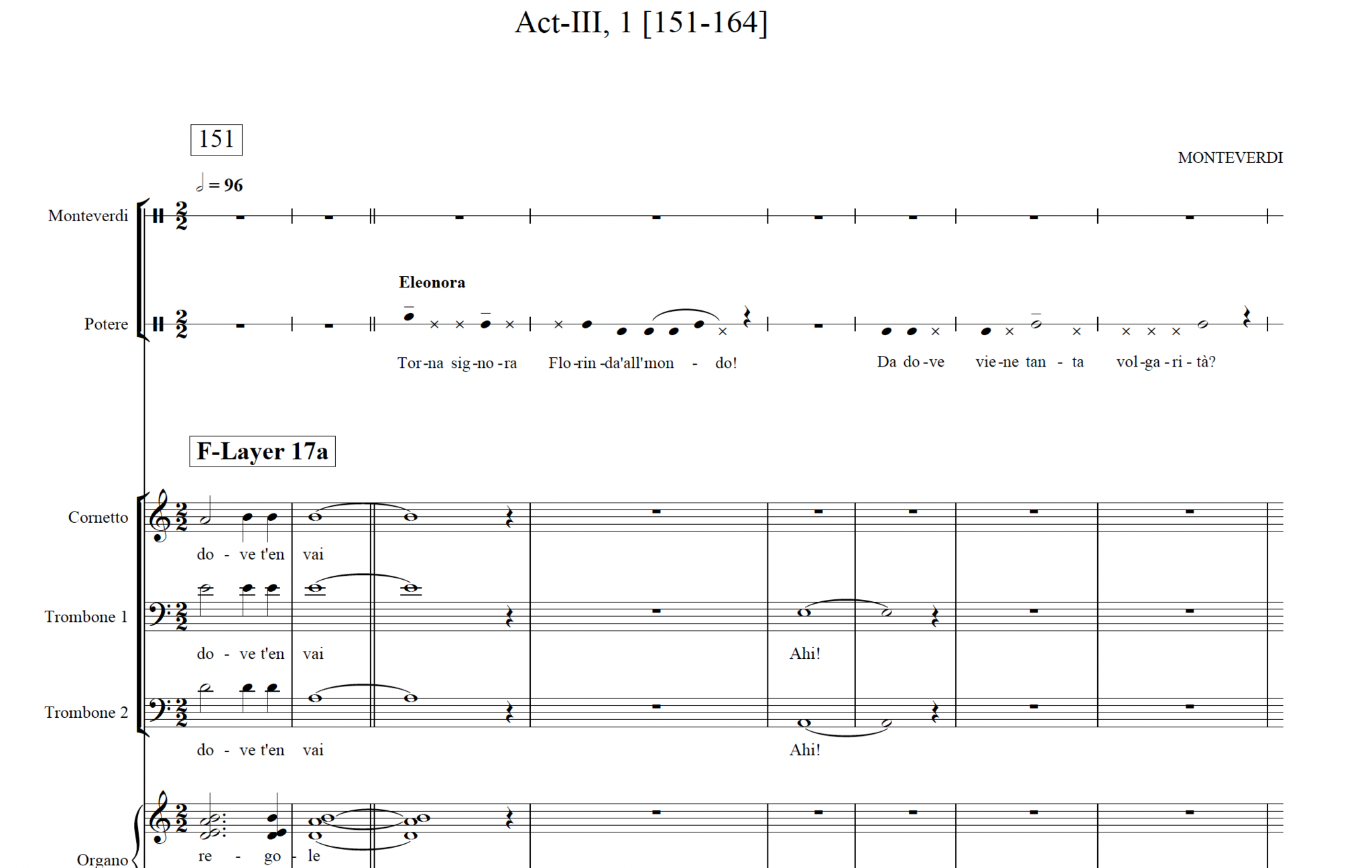

· In the new music: music for the texts, which follows the drama directly; and two ‘Cantus Firmus’ layers: the Monteverdi Layer and the Fate [or Clock] Layer.

These two layers cover the full instrumentation, separating it into two sections, roughly strings versus winds.

The violone (the bass, the ‘fundament’) is the only instrument that plays in both layers.

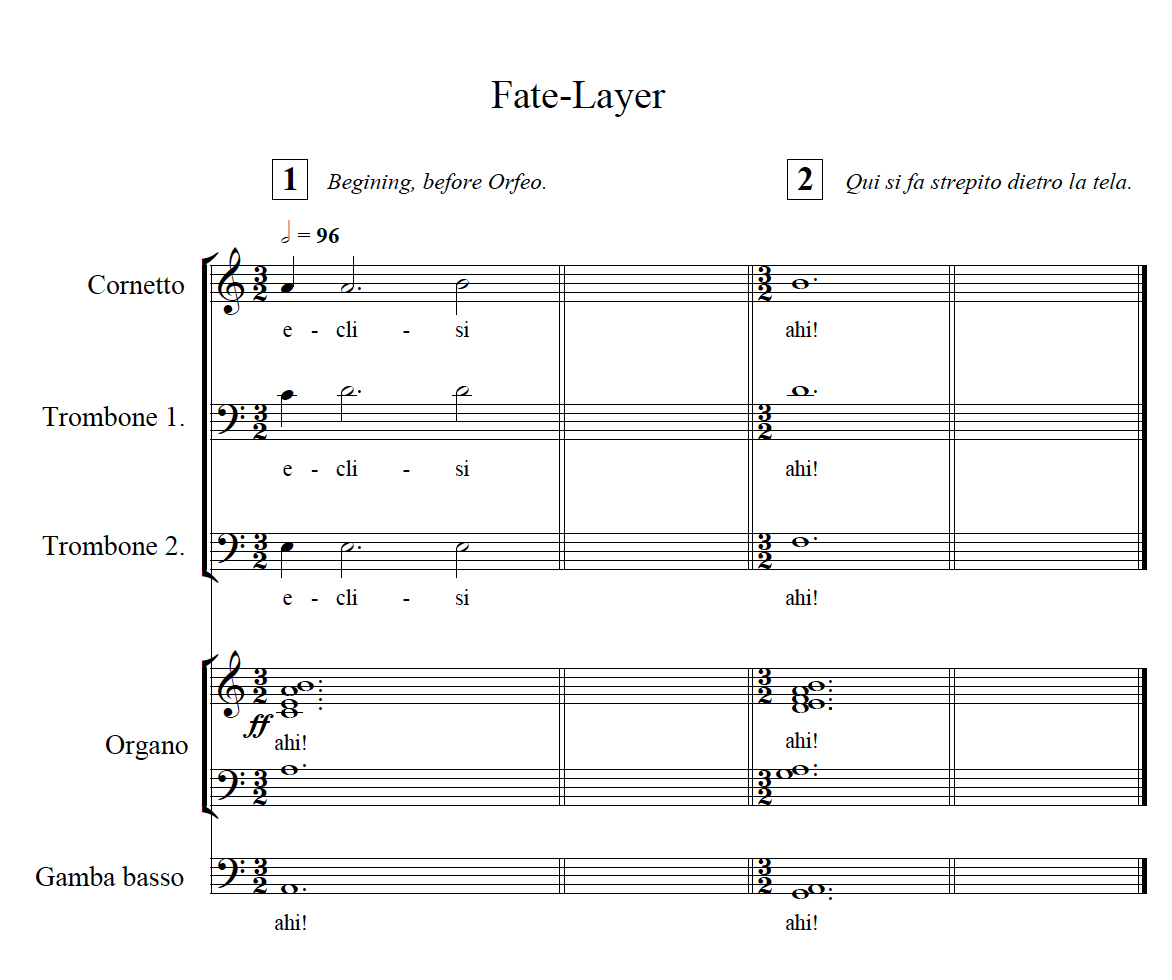

1. Fate [Clock] Layer [‘F-layer’]

Instrumentation:

- cornetto

- 2 trombones

- organ

- violone

This layer is independent of the drama and functions like a clock. It starts the opera (beginning of Orfeo). It represents the ‘noise’ when Orfeo turns his head. A sand clock rules it, and every time the sand clock has to be turned because it’s empty, a ‘sound block’ is played. The intervals of the clock-turning can be composed, with any time interval we like. We can design it in a way it also can sound on specific dramatic moments. We can also (partly) fake fate, set it to our hands, but the suggestion should be that we are in the hands of fate, of course.

The Fate Layer consists of 85 ‘blocks’ [moments]. In the score each block is separated by a one bar rest. This bar rest can take any amount of time. The score is not a conventional score to be played from beginning to end, as it is just a catalogue of 85 possible blocks. The sand-clock will decide when a block is played. Therefore it is not completely predictable when a block will actually sound during the performance, because the timing of the drama can differ (slightly) from one performance to another. This means the performers can suddenly be unexpectedly interrupted by it, and so will have to decide on the spot how to react. During the rehearsals we will have to invent how to do this.

The layer is based on the harmony of the Lamento della Ninfa.

Playing this layer means expressing a clock, fate, a structure.

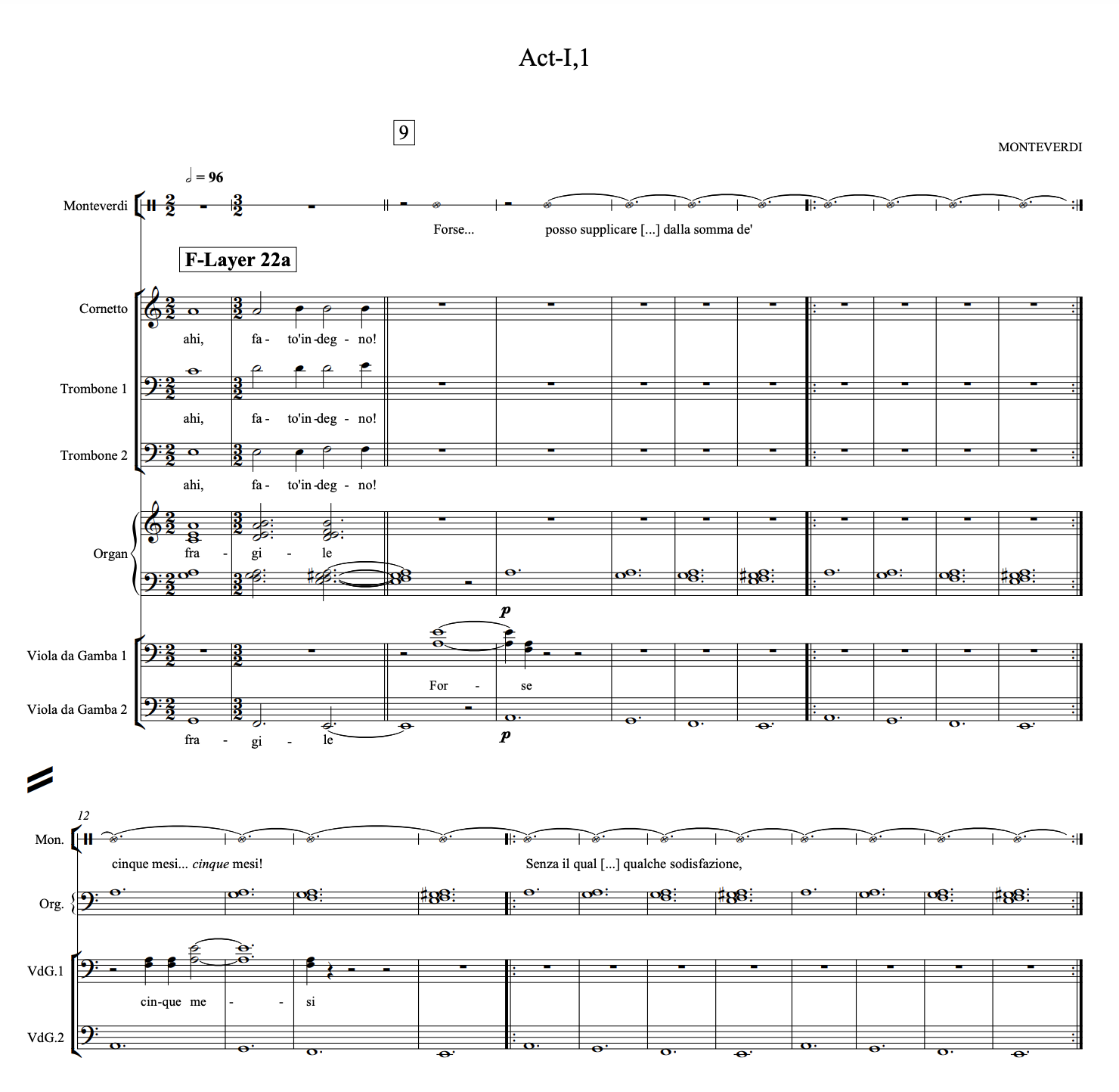

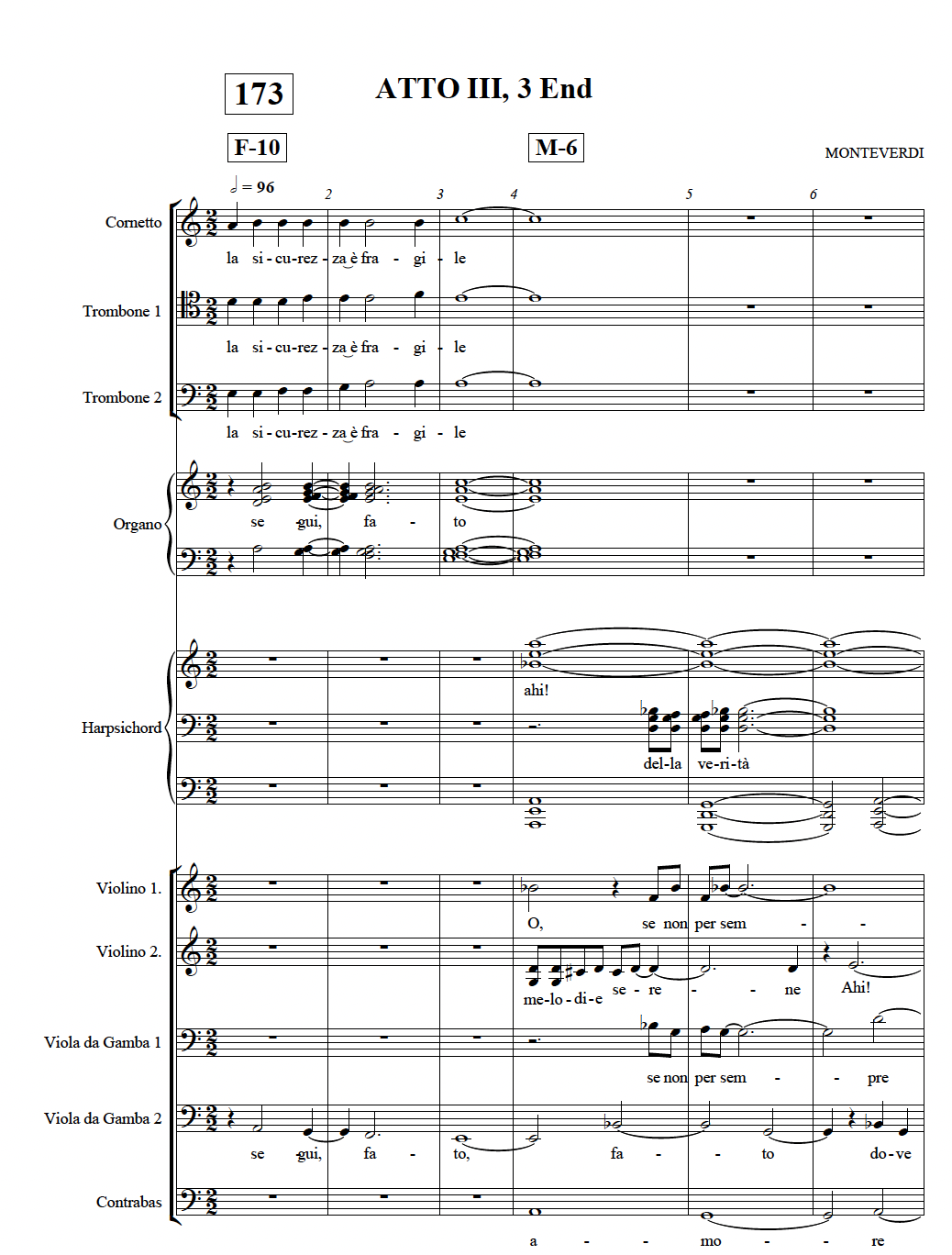

2. Monteverdi Layer [‘M-Layer’]

Instrumentation:

- 2 violins

- 2 gambas

- violone

- harp / harpsichord / lute

This layer, which consists of 64 ‘blocks’, also separated by a rest like in the F-Layer, is connected to the character of Monteverdi, the only character who is on stage during the whole performance (except maybe during the Lamento?). It can be directly connected to when he speaks but also to his movements when he is not speaking. It does not always have to be complete all the time: it can sound partly – only one or two voices of it, or a shortened version, possibly connected to one of the other characters. For instance, the accompaniment of the other characters can be derived from it. For the composers, the layer provides musical material that can help bring unity to the overall musical layer.

When performing a block from this layer, the musicians should have Monteverdi in mind, as well as the scene he is involved in at that moment. The only things notated are pitch and rhythm. The suggested tempo is just an indication: it can be adjusted to what is necessary at a given moment. Articulation and dynamics are free and can also be adjusted to the moment. The long notes in the score are not to be played as in a modern score but should be adapted to what sounds best at the instruments.

This layer basically unfolds a harmonic structure based on the first phrase of the Lamento. The way the layer is structured provides the dissonances and consonances; they come from a formal structure, a different one than the one Artusi is defending, but it behaves according to strict rules to the same degree as the ones Artusi is referring to. It expresses in this way his complaint that consonances and dissonances switch place (in his attack on Monteverdi’s Cruda Amarilli).

The beginning of the score contains smaller blocks; the ending long blocks. The ending could very well serve as the actual ending of the opera (when all the text is done).

The rhythmical material consists mainly of short and long notes, where the short notes lead to the long ones.

I would like to experiment with playing different voices, primarily from the voices, so I will focus on each melodic line instead of trying to make them fit together rhythmically. The total effect of the sound (harmony) is then a result, more than a goal. By doing this, the harmonic result will be noticed, and you will learn how to ‘play with it’, not just concrete (technically) ‘play it’ but also express harmony.

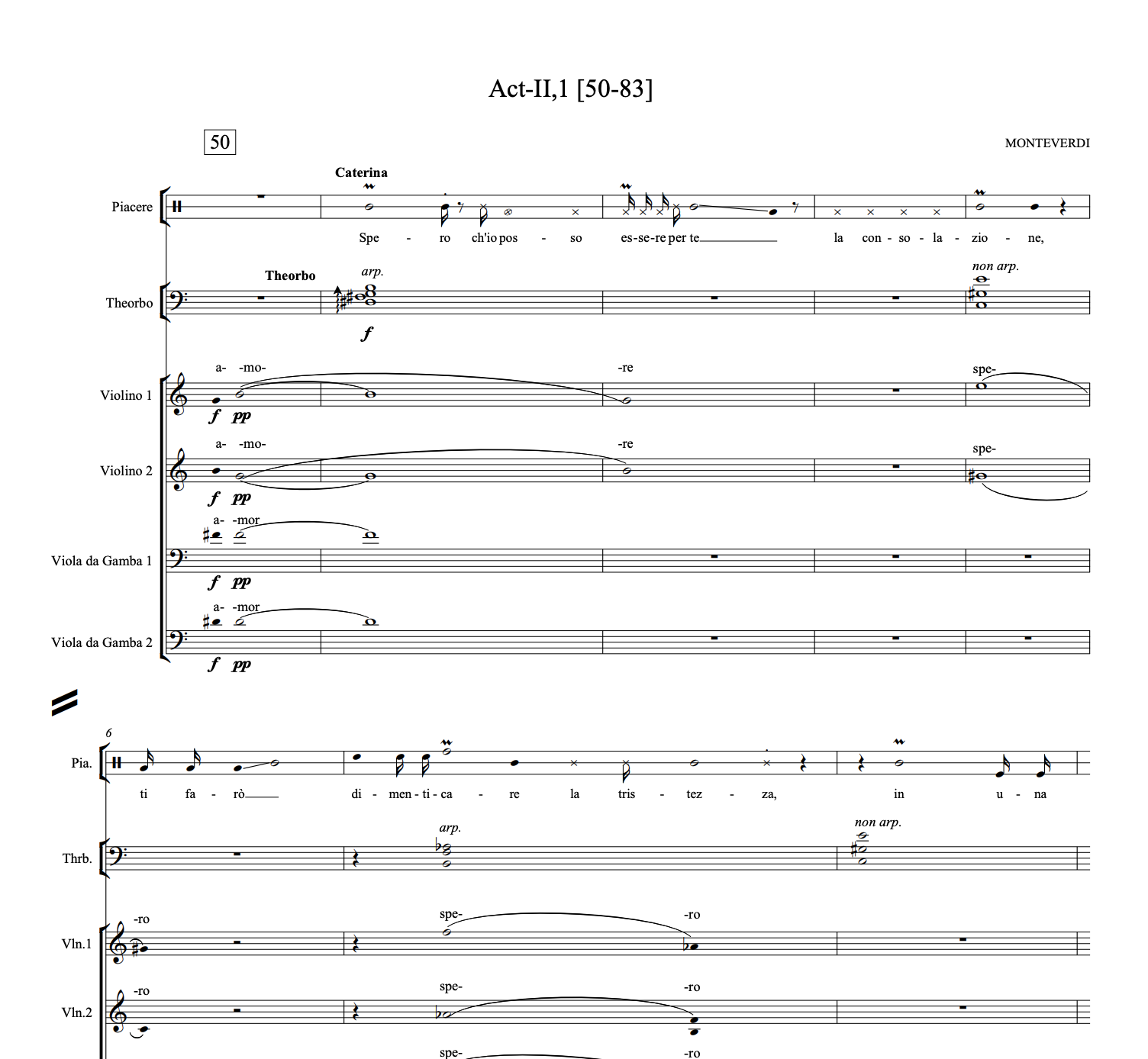

Combining the two layers

The plan is for both layers [F and M] to come together at Caterina’s death in the madrigal Dara la notte. This madrigal will be sung basically a capella, but yet imbedded in the two layers. Every now and then, they sound, sometimes during pauses in the madrigal, sometimes partly overlapping it.

Whether the opera ends with the M-layer or with the F-layer has yet to be decided. Both are possible. Each one suggests something different, of course.

Workshop by Donatienne Michel-Dansac (January 2018).

The team of composers and some of the singers of the project had a two-day intensive on composition for voice.

Donatienne worked a lot with Georges Aperghis and demonstrated some of his work as an example of modern parlar cantando. The choices and their motivations of the team were discussed as well.

INSTRUCTIONS

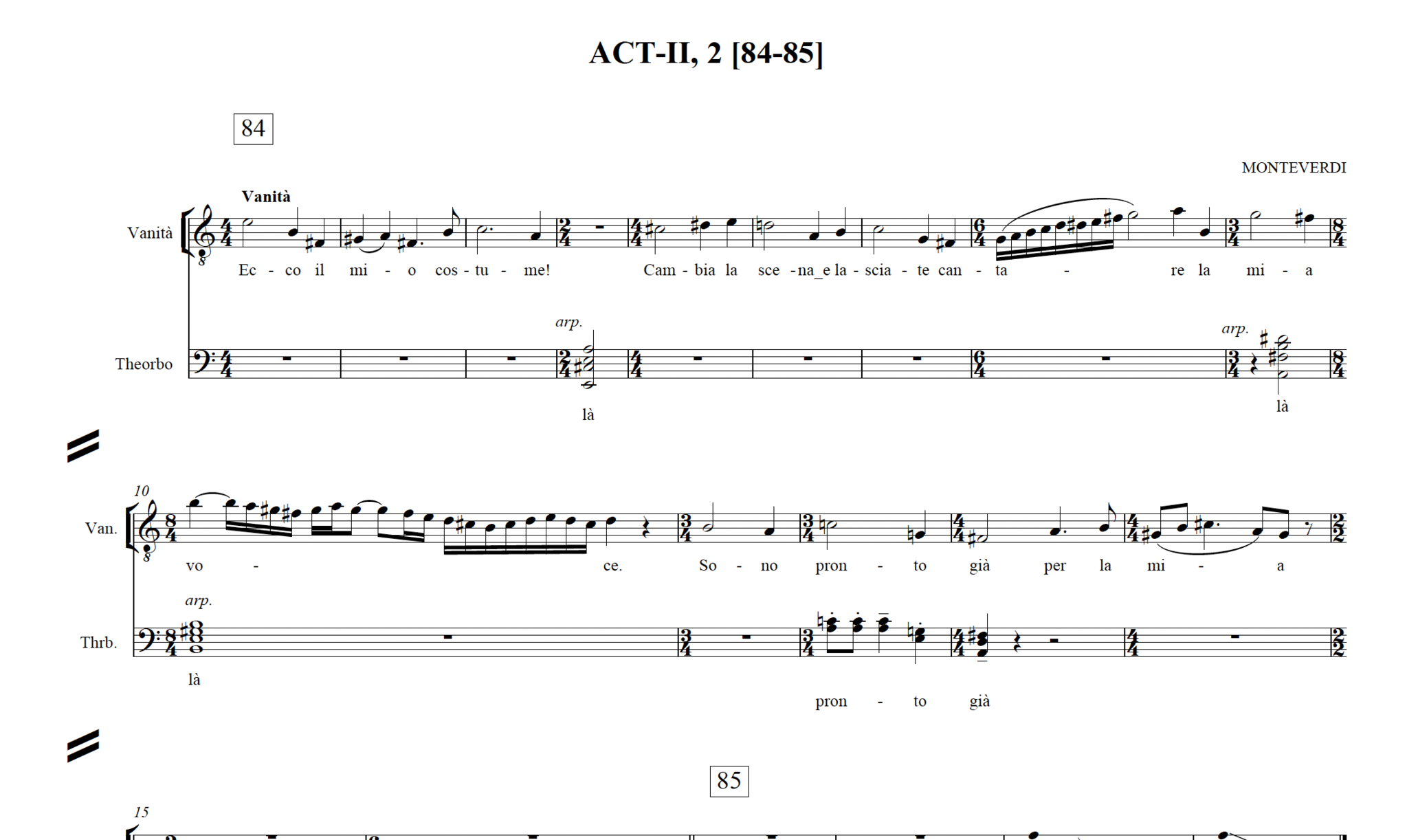

The early music quotations, the two terzetti in Act II Scene 1, all the characters under the archetype of Vanità and the M-Layer (Monteverdi-Layer) and F-Layer (Fate-Layer) apparitions should be considered inside the common use of music writing. Therefore, the following rules apply only to the non-standard notation sections.

Rehearsal marks: the numbers inside squares relate to subdivisions of the libretto.

An important remark is that, in the composition/performance of this Opera, a new practice must be created in which the musicians take a much more active position to the written code (score). The musicians and singers aren’t servants of the composer as traditionally trained in music schools, following classical and romantic practice. Instead, as probably was the case in Monteverdi’s time, every artist involved contributes on stage, during rehearsals, bringing their own ideas and adapting their own talents to the final work.

FOR THE ORCHESTRA:

- Durations

Three durations are given: white notes (without stem), black notes (without stem) and 16th notes. They relate to each other as long duration, short duration and “fast(er)” notes, respectively. In a similar fashion, rests are written as whole note rests, half note and quarter note rests, and 8th note rests, which correspond to long, half-long, short and even shorter silences (primarly coordinated with the vocal parts).

- Bar-lines

Bar-lines work only as visual adds, delimitating shorter divisions of the music. Double bar-lines show the changes between standard notation and the one developed for this Opera. For accentuation and vertical coordination, check the following topics.

- Text

The written texts under the instrumental parts ARE NOT meant to be spoken or sung. They indicate strong ”beats” (according to the accented syllable of the word) and inspire a general mood for the realization of the score.

- Tempo and relation to the voices

The instrumentalists must always follow the tempo given by the singers, coordinate their entrances, and play simultaneously with them.

- Agogics

The use of staccato, marcato, ties and slurs follow common practice.

- Dynamics

The use of dynamics is only a general instruction, as found in the notation of the period in which this Opera takes place. Where no dynamics are given, it must be adjusted to the general mood of the scene and the voice projection of the singers.

- Vertical coordination

Vertically aligned notes are meant to be played simultaneously, as in common practice. It must always be taken in consideration the vertical relation to the singers (and the sung words).

- Unusual sounds

In Act I, scene 2 and Act II, scene 1, the orchestra is requested to play a “weird”, unusual sound with a somewhat funny flavour. It is noted as a “clumsy” cluster.

- Transposition

Guitar and double bass are written and transposed as in common practice.

FOR THE SINGERS

- Durations

Three durations are given: white notes (without stem), black notes (without stem) and 16th notes. They relate to each other as long duration, short duration and “fast(er)” notes, respectively. In a similar fashion, rests are written as whole note rests, half note and quarter note rests, and 8th note rests, which correspond to long, half-long, short and even shorter silences. However, the shape of the note-heads change the sound production, as explained in the next topics.

- Staves

Three kinds of staves are used: common 5 lines, 3 lines and 1 line. Where 5 lines are given, common practice is used. The use of 3 lines denotes a somewhat melodic direction with flexible pitches; the use of 1 line is even closer to spoken language. It must always be directed by the text and the emotions that the singer wants to express.

Whenever a sequence is given in the same line, it shouldn’t be monotonous unless that is what the artist wants to convey. When the pitches in the part change, either up or down, they must be guided by which emotion is appropriate in the moment and fitting in accordance with the instrumental accompaniment. The written part is a starting point; therefore, notes on the same line can fluctuate slightly, and notes on different vertical positions have more difference in pitch. All is relative, related to what is expressed and what fits the language.

- Note-heads and “parlar cantando”

When reading the parts, it must be taken in account the idea of “parlar cantando”. This means that normal note-heads are supposed to be produced closer to common practice “singing”, and X-shaped note-heads are closer to spoken language, even more than in Sprechgesang.

“Parlar cantando” is grounded in declamation, but by the use of speech-like vocal inflections, it has an extra micro-melodic expressive dimension. The role of consonances is also more prominent and varied than in regular singing. One of the main characteristics is that pitches in parlar cantando are rather approximate, whereas in singing, they are precise.

Technically, it is possible to alternate with full singing vocality but not simultaneously doing both.

- Bar-lines

Bar-lines work only as visual adds, delimitating shorter divisions of the music. Accentuations follow the Italian language. Double bar-lines shows the changes between standard notation and the one developed for this Opera. For vertical coordination, check the following topics.

- Tempo

Tempo should be understood according to the character of the text and the action happening in the moment. It must, however, always have a “recitativo” quality, which means that it follows the parameters of spoken language. The characters under the archetype of Piacere have more freedom in this aspect.

- Agogics

The singers’ parts have slurs, staccati and mordent signs. The slurs and staccato follow common practice; mordent should be understood as small ornamentations of the given note, at the artist's discretion. Diagonal lines are also used to indicate glissandi between notes, with the duration of the note where it started. Portamenti should be used whenever it would naturally happen in spoken language.

- Grace notes

Grace notes runs appear in Piacere part as indications of small cadenzas.

- Dynamics

Dynamics should be used as a result of the general mood of a given scene and in relation to the voice production and orchestration of the given part.

- Vertical coordination

The instruments will always coordinate with the singers, and never the other way around. This coordination is made specially by the vertical alignment as in common practice and by the words of the characters in every given moment.

FOR THE COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE

- Body percussion

In several places throughout the Opera, the artists of the Commedia dell’Arte are asked to use body percussion effects. These interventions are notated roughly as common music practice, with rhythms and durations. Sounds can be high, medium or low, depending on their relation to the given line on the score.

It is important to take into consideration that their playfulness should be brought into the performance by creating sound games, improvisation, hoquetus-like structures and any other ideas which fit the composer's and stage director’s vision.

TIME AND PLACE: 1607-08, Cremona and Mantua, Italy.

DRAMATIC PERSONAE

CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI – actor

PIACERE (Catarina Martinelli, Eurydice, Amor, Dafne) - soprano

POTERE (Eleonora de Medici) – mezzo soprano

VERITÀ (Virginia Ramponi Andreini and Arianna) – mezzo soprano

VANITÀ (Francesco Rasi, Orfeo, Apollo and Teseo) - tenor

RAGIONE (Daedalus, Giovanni Maria Artusi and Ottavio Rinuccini) – bass-bariton

COMICI FEDELI – a group of actors/ choir

ORCHESTRA

2 Violins

2 Viola da Gamba

1 Violone

1 Theorbo / Guitar

1 Cornetto

2 Trombones

1 Harpsichord/ Organ