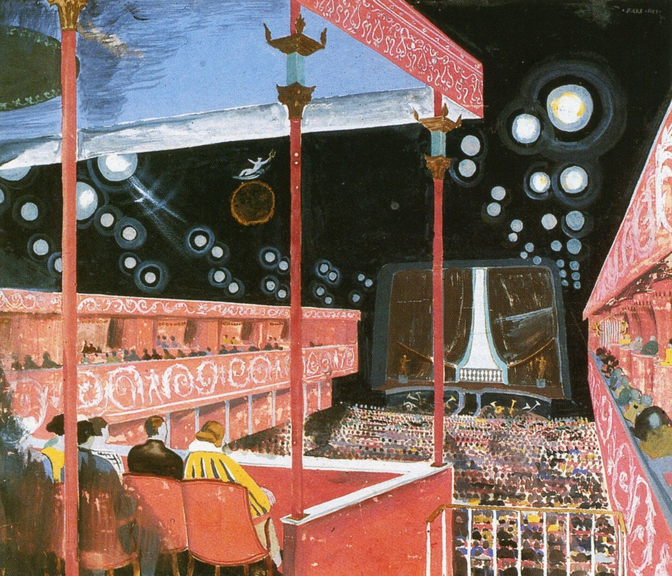

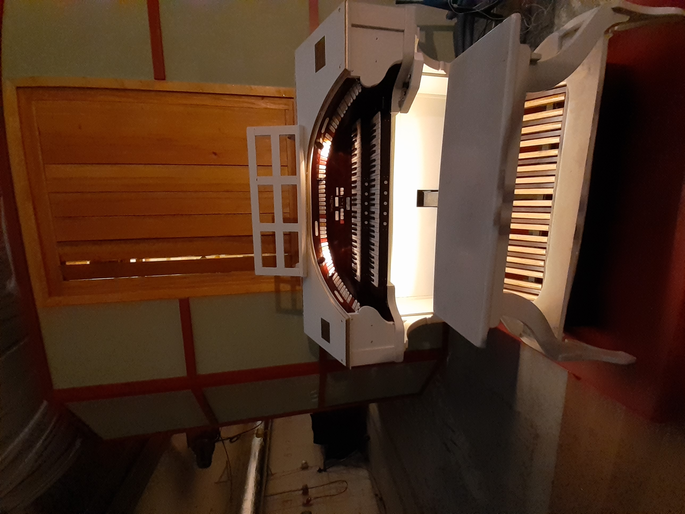

Under stjärnvalvets drömmar/Under the starry futureis a 19-minute, MIDI-driven composition for the Skandia theater organ, a 1926 Wurlitzer Unit Orchestra instrument that was refurbished and given a new home in the Reaktorhallen(The Reactor Hall, or “R1”) over the entire year of 2021. R1 is a huge, cavernous former nuclear reactor hall, several stories underground, hewn out of solid rock. The work is a collection of contemplations on the city of Stockholm, the history of lost optimisms about the technological future, the modernisation so prevalent during that era in Stockholm and, of course, the film and cinema ethos that goes together with this instrument. Two behemoths of the 20thcentury – the grandiose early cinema, and the heady, earlier days of nuclear science – live in this space as spectres, strangely anachronistic.

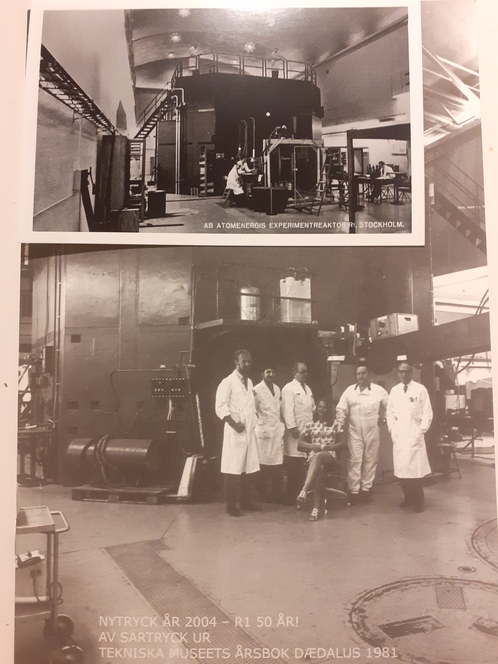

The organ stood in the Skandia theater on Drottninggatan from 1927 until the theater’s controversial renovation in 1943. It was then packed away until recent years, when a cooperation between the Skandia Organ Society and Kungliga Teknologiskahögskolan (The Royal Institute of Technology, or “KTH”), moved it into R1, which is on the KTH campus, where it was renovated and brought back to life. R1 was Sweden’s first nuclear reactor, which operated from 1954 until 1970. The reactor was removed, and the cavern where it was housed cleared of all radioactive traces in the 1980s. In 1998, a group of professors and researchers at KTH sought support from the state for collaboration with artists, suggesting that KTH should create a meeting place and stage for experimental work in the former reactor hall. After some years of testing and renovations, R1came under the directorship of KTH in 2007, and has been a combination of museum, cultural center, seminar room, studio, lab and more ever since.x

This year fell during the covid-19 pandemic, so there was very little happening in the city while I spent long nights working in the former reactor hall. The campus was eerily empty for the majority of the time I was there, adding to the spectre-like feeling of the room. Part of the site-specificity of the work is situated with the organ itself. The organ, which was specially designed for cinemas, was originally brought to Sweden to be the musical centerpiece of the Skandia theater. To that end, I have included some quotes of music in a more traditional, cinematic style of the time.

The piece works specifically with how the organ sounds, reverberates and distributes itself across the unique chamber. Reaktorhallenis in a vast cave, several stories high, and as wide as two good sized churches. Sound moves in the hewn stone room in marvellous ways; the walls create a doppler-like, sonic effect of altered pitches slapping back from the walls, and there are places where multiple, delay-like echos reflect back to shorter sounds, some with marked motion in the space of the room. Of course, there is also a long reverberation, which is always coupled with the sound of the organ’s mighty, steel fan, and other fans, far off in the ceiling and outer reaches of the hall.

The artificial heavens painted on the reactor hall ceiling are animated as a terrible and other-real halo of technologies that should never have been placed so close to a city center, but where the blue skies of optimism for the future prevailed over common sense. The grandiose and short-lived history of the instrument’s hey-day in the Skandia theater, before yet another unpopular Stockholm renovation in 1943 saw Asplund’s starry sky shut off, and the organ packed away in boxes, is ghosted in snatches of theater melody.Echoed, too, is August Strindberg’s poet vision in his 1906 collection of poems about Stockholm, Gatubilder (Street Images):

[...] och därnere längst i mörkret

Syns en dynamo som surrar,

Så det gnistrar omkring hjulen;

Svart och hemsk, i det fördolda

Mal han ljus åt hela trakten.x

[...] and there, far down in the dark,

Is a dynamo that whirs,

So sparks fly ‘round the wheel;

Black and terrible, in the deep

It grinds light out across the whole expanse.

The methods of composition in Under stjärnvalvets drömmar were mixed. As a whole, the entire piece is a MIDI-driven work, where I recorded and programmed different sections of MIDI material into the Reaper DAW program, to and from the organ, which is MIDI-playable. and the MIDI file containing the final version of the piece is also its score. I made it in a very similar way to the multi-channel electroacoustic works I composed earlier in the project, generating “strips” of material in the DAW, then cutting them apart and placing them where they should go according to a sectional score.

The work begins with this material, mimicking a rather flummoxed review of a concert given on this instrument when it first arrived in Sweden:

Suddenly the sound dies back, and in the next minute jumps forward again with the tones of a big band, with saxophone, drums and all the accoutrements, thundering out ‘Valencia’ with a lively swing. Before you have a chance to recover, a still violin solo with piano accompaniment is heard; one last bow-stroke, and then the air is filled with a twittering choir of birds, who are then frightened into silence by the rumble of thunder, with storm and rain.x

After a final flock of birds fleeing a foley-work thunderstorm, the piece goes into its real beginning: a transposition of the Hesa Fredrik emergency warning system, whose distinctive city-wide horns are tested each month in readiness for an emergency.x The piece is made as a contemplation of the future that arrived and the future that did not, singing over a melancholy drone that is made to tremble and shudder the hall through its unique acoustic properties. Another cinematic-influenced section follows, where a higher, beating cluster made with horror films in mind is thrown against the reverberating chamber by the wooden doors of the volume pedal, inter-spliced with ghostly snatches of popular tunes from the era the organ stood in the theater. Then there comes a quiet, but rapid, meant to evoke the operations of the former reactor with the optimism about its potential uses that twined together with its more sinister aspects at the time it was in operation. This melts into a robotic, ever more mad section built from the materials of another old cinema song, Paper Moon. The ceiling in the Reaktorhallen is blue, a painted ”sky” above, made so for the health of the scientists working there.x It is a strange parallel to the Skandia Theater, designed by Gunnar Asplund, with a starry night “sky” made of lights over the audience. This construction was ripped out in 1943, during the same unpopular renovation that saw the organ packed away for many decades. And these artificial skies speak to the modernistic bent of the aesthetics of those times, where artificial and mechanical wonders were seen as being able to rival the heavens. Finally, the piece goes into a reworking of material from Aniara, Sweden’s science fiction opera, depicting the people of the earth all living on a spaceship which is meant to be headed for a wonderful new planet but has, in fact, become lost in space.x The work ends with grandiose “brass” choirs, sinking back into the melancholic drone, which gives way over the last moments of the piece to machinery, trains and wind, as imitated by the organ’s Foley effects

The way the materials were created differs for each section of the piece. I have recorded all the quotations of theatrical organ playing myself, recording first the bass, then chords, then melodies and finally embellishments of each show-tune or popular song I quoted individually, then speeding them up to match the tempo a trained theater organist would have played them at. For this work, I listened to a CD of organists playing the instrument, and also attended a concert put on by the Scandia Organ Society, featuring a virtuosic theater organist.x It was with these in mind that I made the snippets of traditional cinema organ music in the piece.

Some sections, like the drones in the piece, are somewhat edited improvisations. In addition to this work, there are a number of long improvisations I recorded, in order to generate material and learn how to work with the instrument. I cut them shorter in some places for the overall timing of the piece, took out segments I did not feel matched the work, and added volume pedal work to some in order to use the vast sound of the instrument to interact more viscerally with the room. I also clipped together theater organ material with higher cluster material.

Some sections of the piece are generated with SuperCollider patches. Here the idea was that an algorithmic mode should move faster than human hands ever could. In one section, this is punctuated with machinic percussion from the organ’s system of foley effects. I have also incorporated the foley effects into drones and other denser materials as sound colorations, in addition to using some as the objects they depict. There are birds in the opening introduction, which become part of the great, brooding drone in the first section of the piece, as well as a rolling timpani, both of which return at the work’s conclusion. The section drawn from Paper Moon is also a SuperCollider patch. Here I programmed in segments of the melody, and had the program re-transpose it at different points along its course. It is played at broken, robotically slow speeds, rising to rapidly swarming tempos, building into a mad cluster which sweeps across the room, and is altered by the volume pedal and the stone walls.

This combination of freely improvised material, carefully hacked together theater music, foley work, separate playing of the volume pedal, and algorithmically generated material reflects the way I have observed some film-makers working: some cutting together layers of film in collaging techniques, others hacking together many different methods of assembly in order to achieve a desired end result that may not resemble any of them, taken solely. So the piece, itself, is a Foley-work of the things it depicts.

My deepest and most heartfelt thanks go out to Leif Handberg, P.O. Schultz and the Skandia Organ Society for the opportunity to create this work.

After spending a year in the space, I gave a concert on December 21, 2021. I invited two keyboardists whose work I admire to come and work on the organ as well. Milton Öhrström plays pianos, synthesizers and organs in a great number of varied projects. For his piece, he made a patch in PureData that cycled through the stops in modules of rapid clusters, and performed an improvisation structure on the instrument as it transformed. Klas Nevrin is a pianist, synthesizer player and artistic researcher. He brought modal materials to the instrument from his wide-ranging studies of different microtonal and other systems of improvisation, as well as playing very much with the tonal qualities of the room's unique acoustic properties. Watching and listening to these two established keyboardists work inspired and informed my own process with the instrument. I also learned about the acoustics of the space by playing my violin in it. I include the last rehearsal of an improvisation structure I created for the concert. These recordings can be heard above.