Title page Introduction Theoretical Background Intervention Conclusion and Discussion Acknowledgements Appendixes Bibliography

Embracing vulnerability

Dr. Brené Brown is an American research professor who spent her career studying the concepts of courage, vulnerability, shame, and empathy. Brown wrote seven books and her TED talks have been widely viewed. In her books and TED talks, Brown speaks about shame, vulnerability and connection.

Over a decade of research on vulnerability taught Brown that vulnerability is not weakness. To feel is to be vulnerable. To believe vulnerability is weakness, is to believe that feeling is weakness. The emotional exposure, risk and uncertainty we face are not optional, says Brown. The only choice we can make is whether we engage. Are we going to show up and let ourselves be seen, or will we sit on the sidelines, waiting to be perfect and bulletproof, before we enter the stage?

“Our willingness to own and engage with our vulnerability determines the depth of our courage and the clarity of our purpose; the level to which we protect ourselves from being vulnerable is a measure of our fear and disconnection.” (Brown, 2012)

As Brown shows in her book ‘Daring Greatly’ (2012), psychology and social psychology have produced very persuasive evidence on the importance of acknowledging vulnerabilities. From the field of health psychology studies show that perceived vulnerability, meaning the ability to acknowledge our risks and exposure, greatly increases our chances of adhering to some kind of positive health regimen. The critical issue is not about our actual level of vulnerability, but the level at which we acknowledge our vulnerabilities around a certain illness or threat. (Aiken, Gerend & Jackson, 2001) From the field of social psychology, influence-and-persuasion researchers conducted a series of studies on vulnerability. They found that the participants who thought they were not susceptible or vulnerable to deceptive advertising were, in fact, the most vulnerable. The researchers’ explanation for this phenomenon says: “Far from being an effective shield, the illusion of invulnerability undermines the very response that would have supplied genuine protection.” (Sagarin, Cialdini & Rice, 2002)

When it comes to artists, Brown says: “To create is to make something that has never existed before. There’s nothing more vulnerable than that.” When performing, musicians can’t escape vulnerability. Performing is being vulnerable, is experiencing vulnerability. “When we pretend that we can avoid vulnerability we engage in behaviors that are often inconsistent with who we want to be.” We consciously or unconsciously arm ourselves against feeling vulnerable. We numb, perfect, pretend or try to make everything that is uncertain, certain. This of course is not what musicians should be wanting on stage. Numbing might sound like a clever solution, but as Brown explains, we can not selectively numb emotion. When we numb vulnerability, we also numb fear, excitement, joy or whatever other emotion. Emotions are of great importance to perform with full engagement, to achieve a state of ‘flow’. The main role of music is to convey emotion and to move the audience.

Brown states that we are wired for connection, that connection is what gives purpose and meaning to our life. She also explains that we must allow ourselves to really be seen, in order for connection to happen. But we cannot let ourselves be seen and heard if we are terrified by what people might think of us, or of our playing. If we are hiding out of shame, we won’t connect. Shame resilience is key to embracing vulnerability. If we want to be connected, want to be fully engaged, we have to be vulnerable.

In her research Brown found that connection is a result of authenticity. (Brown, 2010). She also states that vulnerability is not only the core of shame and fear and our struggle for worthiness, but appears to also be the birthplace of joy, of creativity, belonging and love and the source of hope, empathy and authenticity. (Brown, 2012). Combining these two findings led me to the following hypothesis:

How can performers embrace vulnerability? Brown's research has shown that the best place to start is with defining, recognizing and understanding vulnerability. When we understand what vulnerability is and recognize how we arm ourselves against it (by numbing, perfecting, pretending etc.) we can start disarming ourselves. At their core, all strategies of disarming are about "being enough", and, believing that we are enough. We have to believe that showing up, taking risks and letting ourselves be seen is enough. To embrace vulnerability, we should not walk away from, but appreciate our cracks, our imperfections. For it is our nature to be imperfect. Of course, embracing vulnerability is not a substitue for deliberate practise and strategic preparation. Being well prepared for performances, allows for vulnerability. This is integrated in the strategies for embracing vulnerability on stage, mentioned in the next chapter.

"When we believe that we are enough, we stop screaming and start listening." (Brown, 2010) When we believe that we are enough, we stop trying to impress and prove, and can start making music from our heart, fully engaged and in connection with ourselves, our music and our audience.

Back to Introduction Continue to next page

Expert interviews

In order to explore the topic further I asked 3 experts in the field of psychology about vulnerability and music making.

Introducing the experts

I interviewed three Dutch psychologists around the theme of vulnerability. First of all, Christy Dokter, who is a Dutch psychologist and coach with her own practice ‘You are brilliant’. Christy believes every woman has unique talents and potential and has helped many women to blossom. Secondly, I interviewed Laurie Cleuver, a Dutch psychologist with her own practice in The Hague. Laurie has studied for many years to become an expert in the field of psychology and neurofeedback. Lastly, Martine van der Loo. Martine is not only a psychologist, but also solo flutist with the Residentie Orkest in The Hague. Martine is specialized in coaching professional musicians, conservatory students and advanced amateurs. Her own experiences as a musician are of great help in her work as a psychologist.

Questions asked

I started the interviews asking the psychologists to describe vulnerability in a few sentences. Then, we spoke about embracing vulnerability. What does it mean and how can we do so? Why are we afraid to be vulnerable? Leading to the next question: which boundaries are helpful when choosing to be vulnerable? Since I in this research assume there is a link between vulnerability and connection, I asked the psychologists how they believe vulnerability is related to connection. Lastly, I asked for reading recommendations to learn more about vulnerability.

To Martine van der Loo I asked some extra questions, regarding her experience as a musician and work with musicians. We spoke about how musicians deal with vulnerability, whether there is room for vulnerability among musicians and what her advice is for musicians to cope with vulnerability.

Click here for the original questions in Dutch (PDF)

Expert interview 1: Christy Dokter (psychologist, helping women)

Christy strongly believes that you cannot talk about vulnerability without talking about courage. Our deepest fear is to be rejected, that is why we are so afraid to be vulnerable and why being vulnerable asks for courage. Embracing vulnerability starts with recognizing and acknowledging our emotions and vulnerability. Christy explained how Dutch people through history learned not to complain, not to talk about emotions and learned to just get things done – no matter our feelings. We, Dutch people, are proud of our intelligence and strong willpower, but must learn to talk about emotions and to accept our vulnerability. Christy stated that music could be of great help in this, for music can open doors and give room for our feelings. She also explained that we need vulnerability for connection. Without vulnerability there is at most a transfer of information, a collaboration. But when vulnerability enters the room, needs and desires come to light, recognition is found and suddenly there is a connection. Christy believes that we are wired for connection.

Regarding the musician, the performer, Christy says that being connected with yourself and your emotions, on stage, is the biggest gift you can give an audience. For if you as a musician connect with your own heart and with your feelings regarding the music, the audience will sense that and because of that, they will be able to connect with you.

Christy asked me: “Are you willing to give your heart to the audience? Or do you just want to play your piece well? If you are looking for connection, you have got to be willing to give (a bit of) your heart. You can decide yourself how much you give. But know this: the audience will sense the difference between a performance where you give your heart and might make some mistakes and a performance where you just do a great job, playing flawless. They maybe can’t tell the difference, they will find it hard to put it into words, but for sure they can better connect with the first one.”

Expert interview 2: Laurie Cleuver (psychologist, expert neurofeedback)

Laurie started off by saying vulnerability is to be defined as the opposite of resilience. The less resilient a person is, the more vulnerable he will be. In the course of the interview Laurie concluded something remarkably interesting: we probably get more resilient by embracing our vulnerability. Nobody is born resilient, but if we learn to deal with our vulnerabilities, our resilience increases. Laurie explained that we are scared to be confronted with our vulnerabilities, because we are afraid of rejection. We are trying to protect our ego, to not have to face ‘negative beliefs’, such as the thought that we are not valuable or do not matter. Learning to deal with our vulnerabilities starts with getting to know our vulnerabilities. We do not always know how vulnerable we are in advance, until we experience it. Next, says Laurie, embracing our vulnerabilities is daring to really go through our emotions: “Science has proven that a strong emotion only lasts for 90 seconds”. The problem is that often before these emotions can eventually take place, we already block them (by fighting, flighting or freezing). If we would accept our emotions and dare to let them happen, they could be over in just 90 seconds.

When talking about musicians, Laurie believes that making music in front of others already is very vulnerable. As a musician you will show something where people can react to, where they can form their opinion on. This brings the musician in a vulnerable position. To keep making music from the heart, irregardless of the fact that people might not like it, takes courage. Like Christy, Laurie also believes that people are not attracted to music that does not come from the heart. People sense the energy, the emotions, the heart behind the music. Audiences are not looking for flawless performances.

Laurie did mention that it is important to in a certain way ‘arm’ yourself when it comes to vulnerability. A way to equip yourself to deal with feedback regarding performances where you have been vulnerable, is to remind yourself that your value is not defined by your success or by other people’s opinions. It is important to realise that not everybody will be touched by or like your performance, but the fact that not everybody loves it, does not make your performance less good. Something else that will help you ‘arm’ yourself, is to decide beforehand how vulnerable you want to be on a certain day or during a certain performance. It is very important to set boundaries, to dose what you will and will not show or tell.

Lastly, Laurie argued that when you are vulnerable, you feel and experience things more intensely. Which can be a beautiful thing when it comes to enjoying, to feeling lively etcetera, but which also asks for carefulness when it comes to receiving negative feedback.

Expert interview 3: Martine van der Loo (psychologist and flutist)

Martine links vulnerability first and foremost to dealing with emotions. Embracing vulnerability has a lot to do with learning to deal with your emotions. How this works? “By facing them”, says Martine. As long as you do not face your emotions, you oppress them and you are building up walls. The problem is that emotions cannot be oppressed forever, sooner or later they will come out. To deal with them in a healthy way, is to face them. The question is: are you willing to do so? It does take courage and ask for extensive self-examination. The boundaries we might need to set when embracing vulnerability are personal and depending on the occasion. Martine believes that the way we handle certain situations and deal with our emotions is partly genetically determined.

Being a professional musician herself and working with musicians in her practice, Martine had plenty to say about vulnerability regarding musicians. In the first place fear is a very real emotion when entering the stage. You are about to show yourself, which is very vulnerable, and you will almost certainly be judged. The fact that the judgment of outsiders – not to mention your own judgement – always lies in wait, makes the job even more vulnerable. Secondly, Martine mentioned that both preparation and level of mastery are of great importance when looking at embracing vulnerability on stage. When the musician does not yet master the piece he is about to perform, he will most likely mainly be busy surviving instead of embracing his vulnerability. Furthermore, also the setting of the performance affects a musician’s will and ability of embracing his vulnerability. One musician finds it easier to be vulnerable when playing in a big hall, while the other thrives in an intimate setting. Note that making recordings is a trade of its own.

The correlation between vulnerability and connection is very clear to Martine. Sharing vulnerabilities leads to connection when answered with understanding. When there is no positive response, or when the response is even negative, you have to arm yourself, which leads to distance instead of connection. However, on stage, musicians are not to be concerned with the response of the audience. When you are thinking about your audience while performing, you are actually distracted, because you are not thinking about the music. Martine also explained that musicians never ought to be overwhelmed by their emotions. The job of the musician is to pass on the music and the story, the emotions of the music, not his own emotions. If the musician does his job well, the audience will be moved naturally.

See Appendix 1 for the audio recordings of the interviews

Continue to next page

Title page Introduction Theoretical Background Intervention Conclusion and Discussion Acknowledgements Appendixes Bibliography

Which elements are likely to lead to a convincing, yet authentic performance?

To perform convincingly, a performer needs to be convinced. To perform authentically, a performer needs to be connected with herself and dare to be authentic. How do we achieve these things? I started listing the things performers need, important criteria for a convincing performance, and came up with things like confidence, technical proficiency, focus, courage and more. After analysing the list, they fell into three categories: Self-efficacy & trust, Focus & flow and Connection. In this research I will look at the effect embracing vulnerability has on these elements.

I will now go into each category in detail.

1. Self-efficacy & trust

To perform convincingly, a musician needs to be convinced of what she is doing. She needs to have a clear idea of what she wants to do and then trust in her abilities to produce the outcome she desires. This confidence in her ability to perform the way she desires is related to self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986). Self-efficacy is not the same as self-confidence. Where self-efficacy refers to people's beliefs of their own competence to complete a specific task, self-confidence refers to an overall or general feeling of competence (Bandura, 1997) To perform well, a performer does not need to have a general feeling of competence, but she needs to believe in her own competence to make this specific performance work, regardless of her overall self-confidence. According to both Bandura and Zimmerman the concept of self-efficacy is particularly important in specific performance settings (Bandura, 1997; Zimmerman, 2000).

2. Focus & flow

Attentional focus (or concentration) is one of the most important aspects that influence the achievement of musical excellence (Connoly & Williamon, 2004; Chaffin, 2004; Keller, 2012) and excellence in motor skills in general (Wulf, 2007). Focus can either be internal or external. Internal meaning that the focus is on the body’s movements, external meaning that attention is given to the result of the movements (Wulf 2007, Wulf 2013) According to Wulf an external focus of attention provides the appropriate mind-set for the musician that is essential for playing successfully in public (Wulf, 2008). Research also suggests that technical proficiency as well as musical expression, the primary elements of a performance, are improved by using external focus. (Mornell & Wulf, 2008) Williams states that when using external focus, music informs technique. “Although one of the main goals of a musician is to play accurately, accuracy is better achieved by focussing on musical intention. Thus, accuracy and facility is a side effect of external focus.” (Williams, 2019)

Whether it is in practising or in performing, it is always important to focus on what you want, instead of what you do not want. Wegner called this the ironic effect: focussing on what you don’t want makes it more likely that the (unwanted) result will happen. (Wegner, 1994)

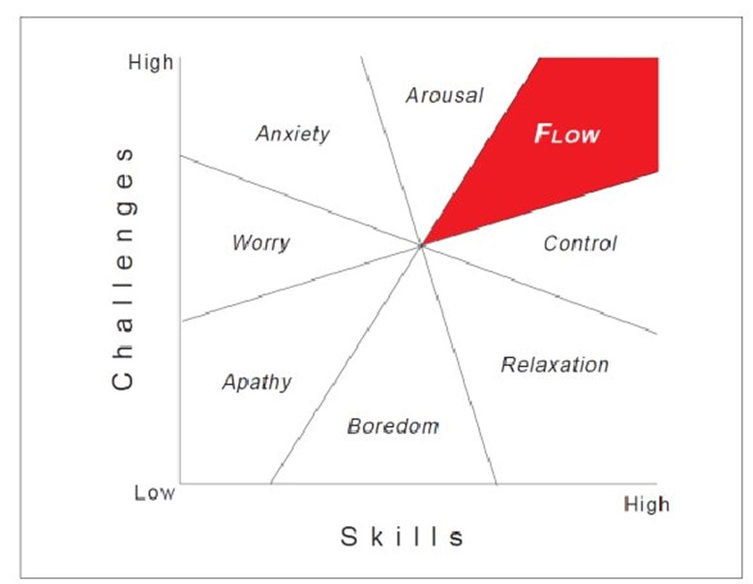

According to Csikszentmihalyi performing optimally is found in a state of “flow”. When being in a state of flow, a performer will have the sense of seemingly effortless movement. (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). It is a state of consciousness where performance is "an almost automatic, effortless, yet highly focussed state of consciousness" where the performer’s concerns about success and even sense of time is absent (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). When a performer is in a state of flow, she will be so occupied by what she is doing, by performing, that she will have no attention left over to monitor time, feelings or complex thoughts. Flow is a state of total engagement, a place where body, mind and emotion are all present, yet not consciously analysed or controlled. To reach this state of flow while performing, the performer has to be trained well and has to have developed technique. In other words: the performer needs to be prepared well. Another prerequisite of reaching flow state is the balance between the challenge a performer experiences and the skills she has to deal with the challenge she is facing. As shown in the figure below, the state of flow is reached when both the challenge a performer experiences and the skills she feels like having are higher than average. In one of his TED Talks Csikszentmihalyi adds that this “channel” of flow will be reached when a person is doing what she really likes to do. (Csikszentmihalyi, 2004)

3. Connection (between me and my instrument, me and my music, me and my audience, me and myself)

The self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) identifies three basic, psychological needs: competence, autonomy and relatedness. The need for relatedness, described as the need to interact, be connected to, belonging, and experiencing caring for others is extremely relevant to this research. Looking at relatedness as a basic, psychological need clarifies why a performer would want to interact and connect with her audience and vice versa. Performing convincingly, yet authentically has not only to do with the connection between the performer and the listener, but also with the connection between the performer and her instrument, the connection between the performer and the music, and the performer and herself.

Usually, the way musicians go about the things listed above, is by trying to control all of it, making sure that nothing goes wrong. The result of this approach can be stiff, over controlled, mechanical playing as well as focussing on avoiding mistakes and of what other people might be thinking. That of course does not usually lead to the desired result: i.e. to a convincing and authentic performance. Embracing vulnerability might be the key to make our performances so much more the way we want them to be.

Next page: Intervention