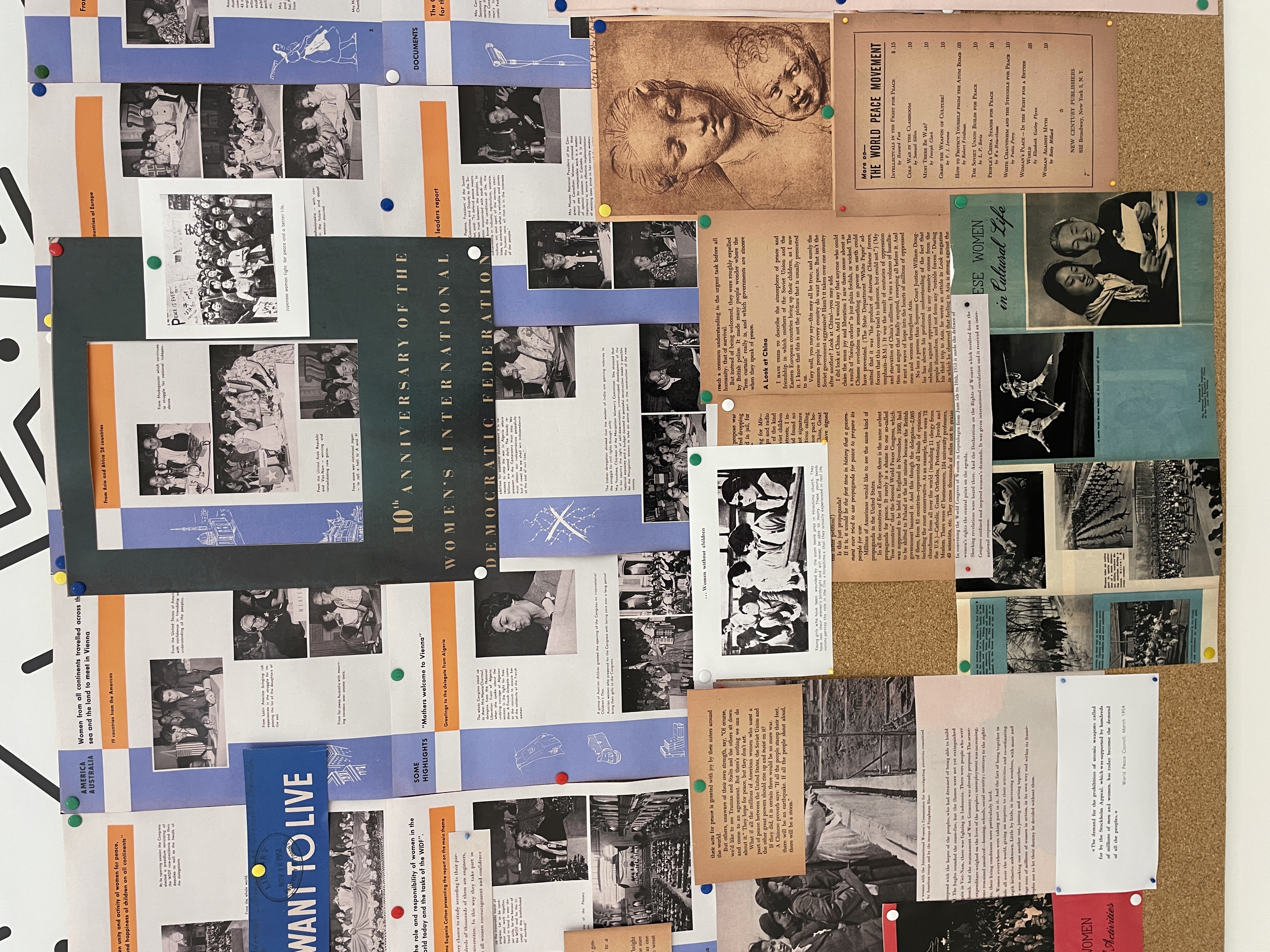

- November 1945 Founding Congress of the Women's International Democratic Federation, Paris

- December 1948 Second Women's International Congress, Budapest

- December 1949 Conference of the Women of Asia, Peking

- June 1953 World Congress of Women, Copenhagen

- July 1955 World Congress of Mothers, Lausanne

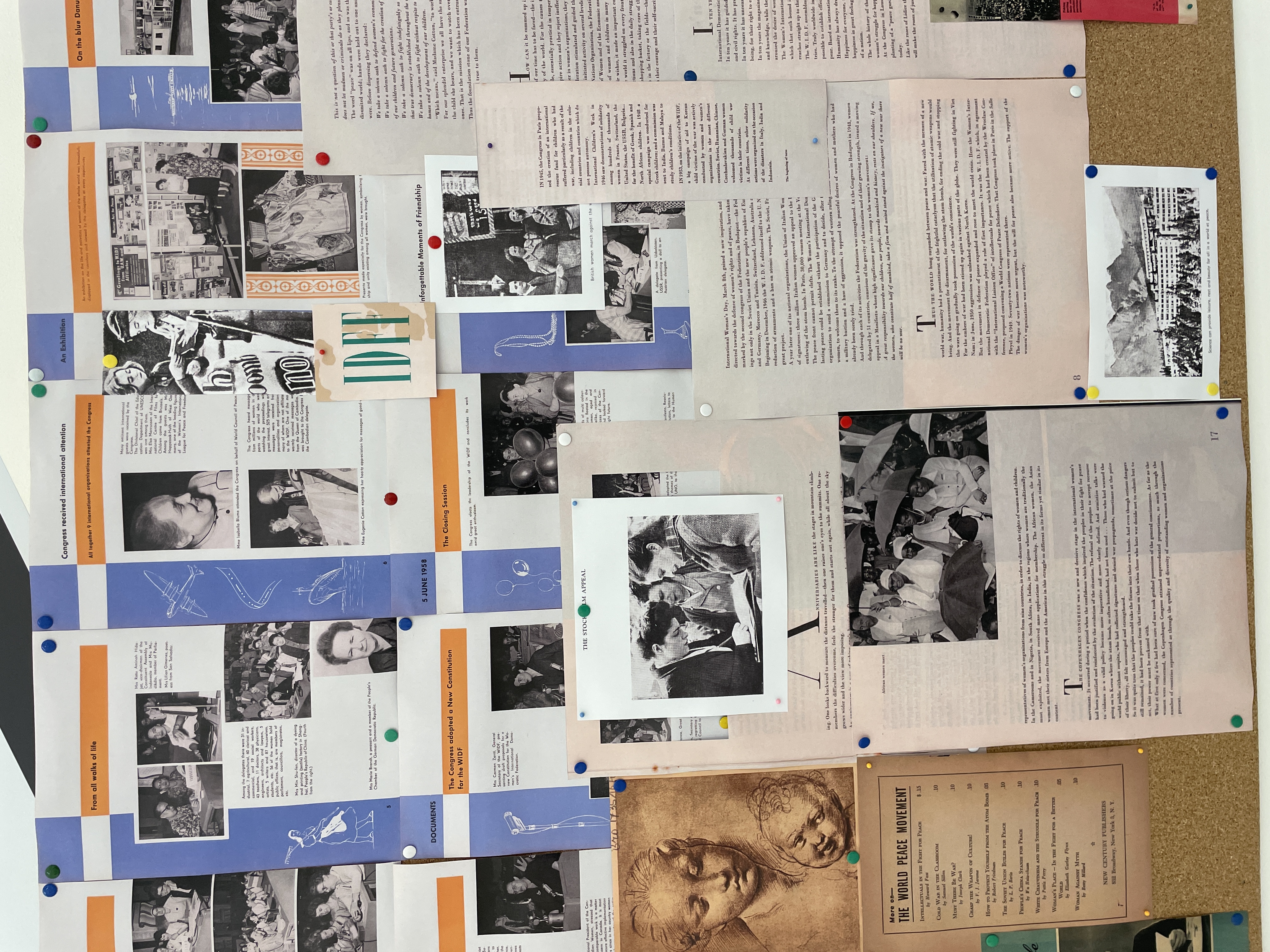

- June 1958 Forth Congress of the Women's International Federation, Vienna

- January 1961 Afro-Asian Women's Conference, Cairo

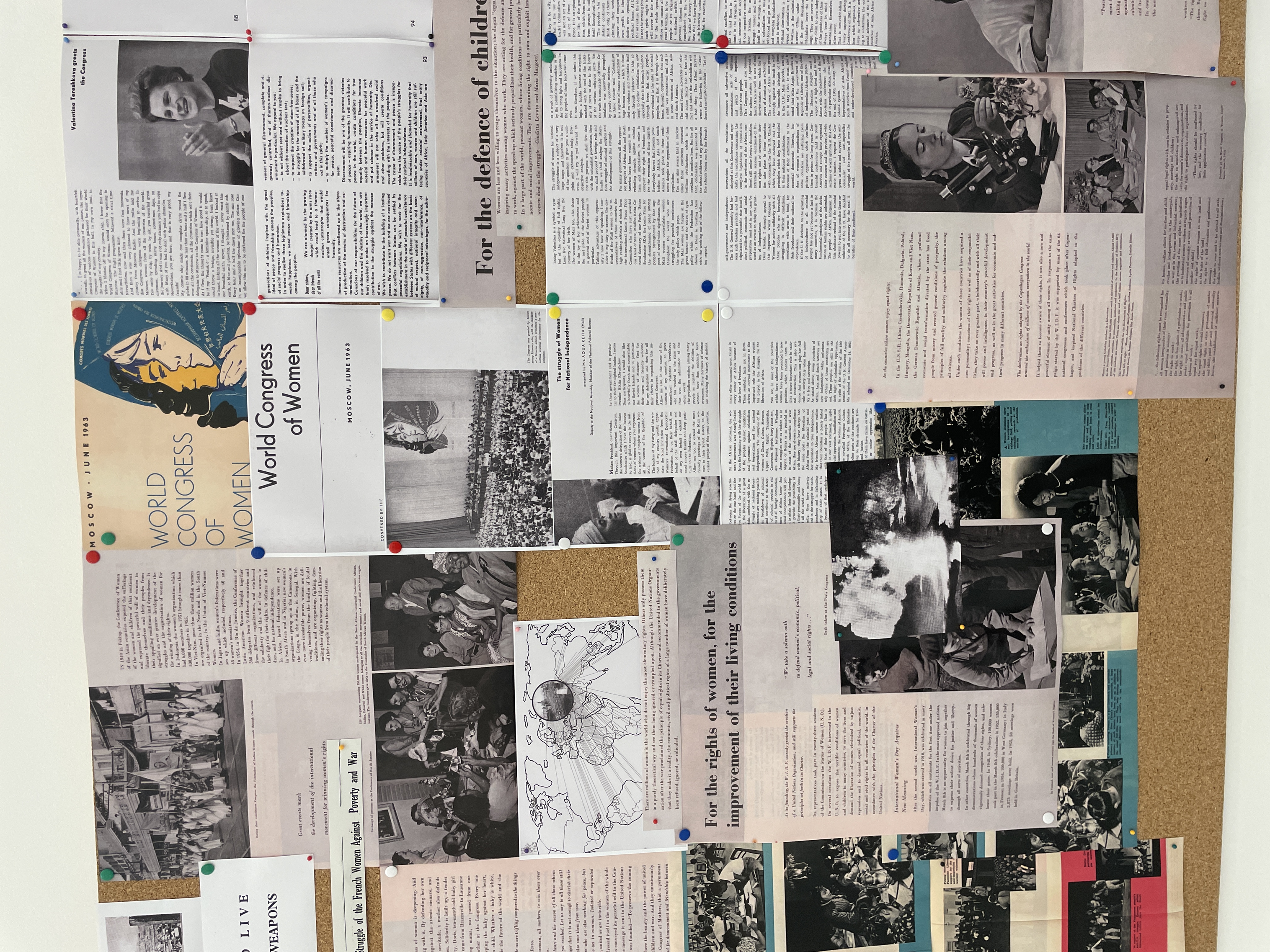

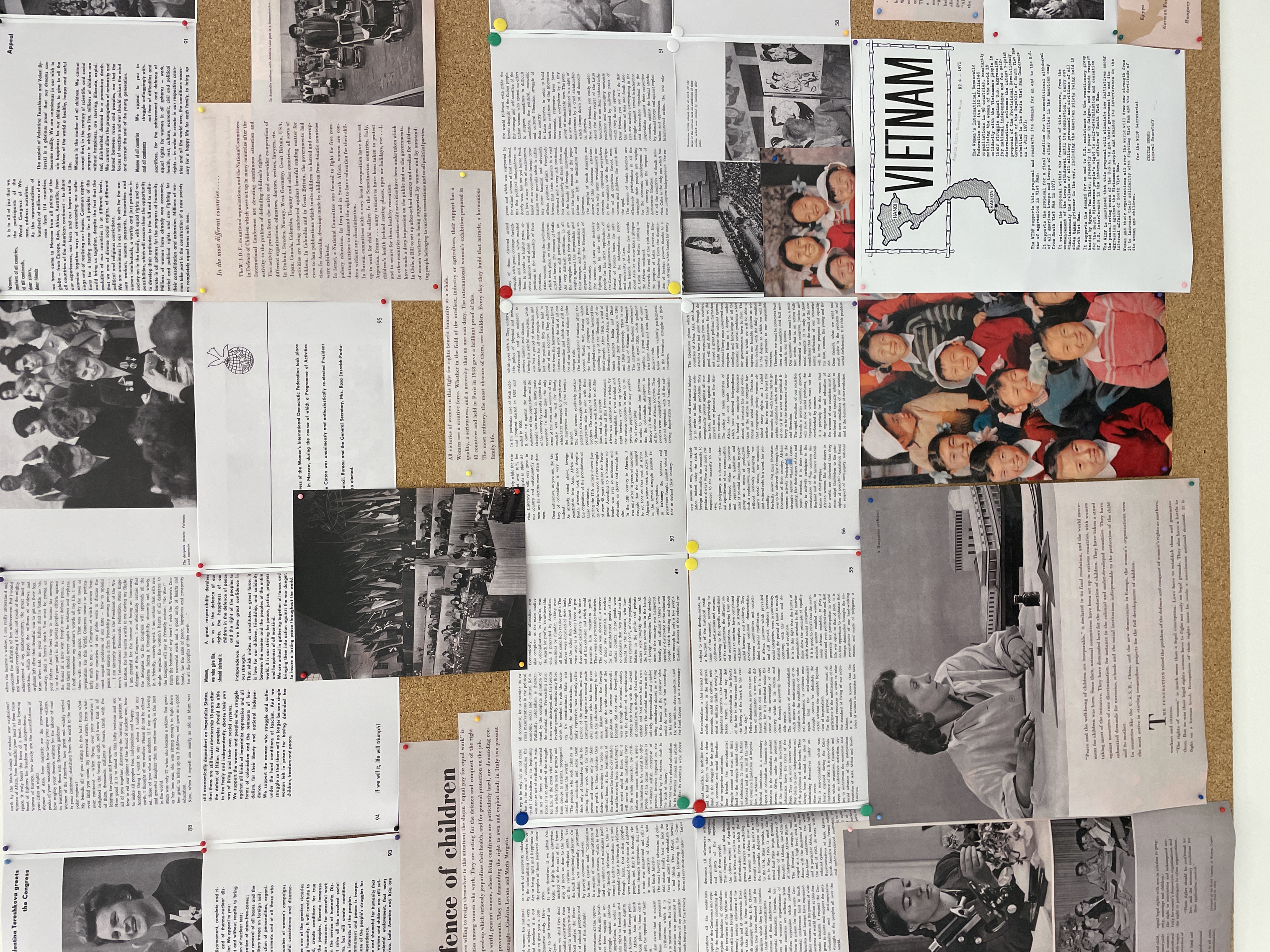

- June 1963 World Congress of Women, Moscow

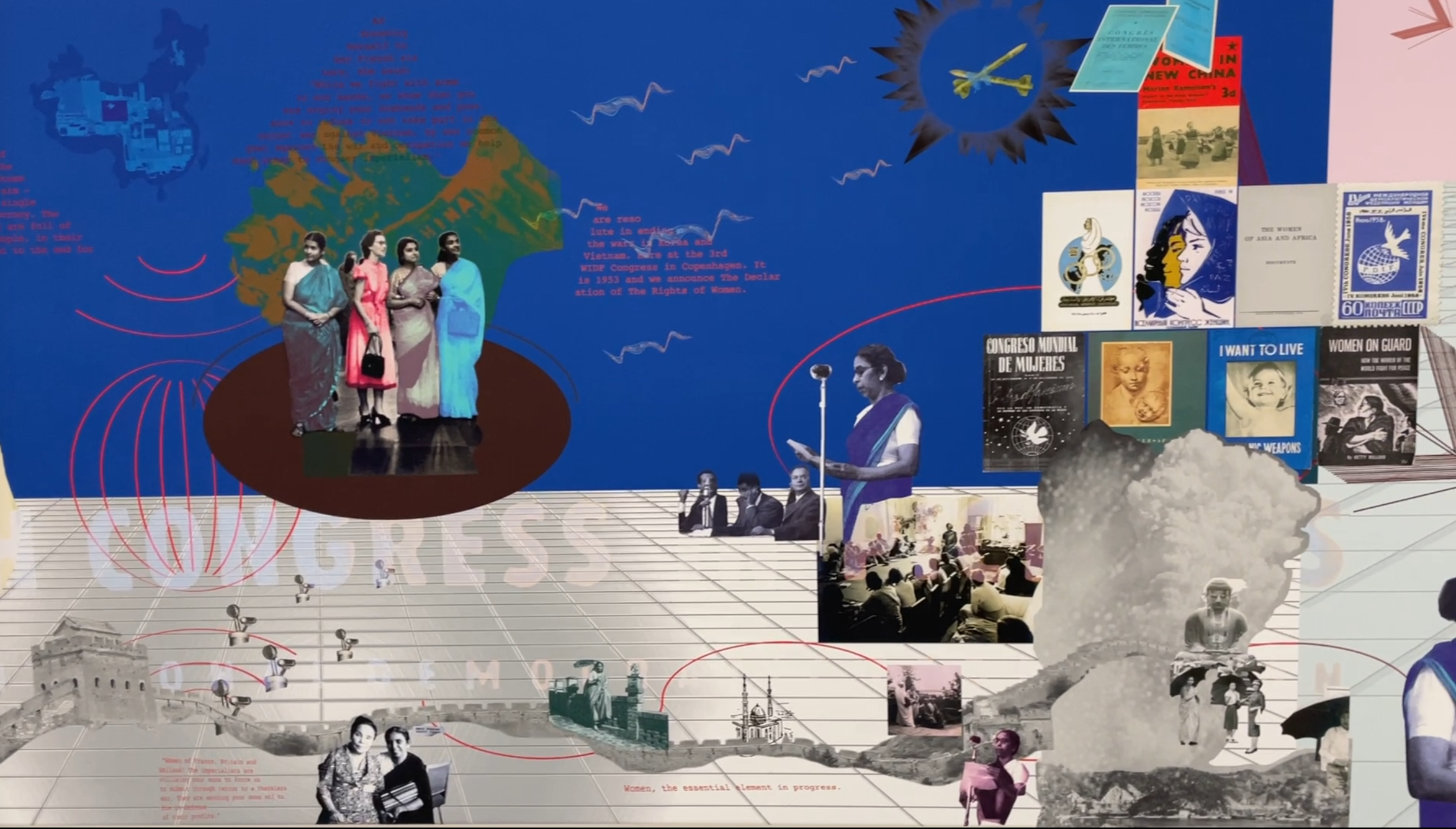

Welcome, everybody. Thank you for coming to Women of the Whole World: A Murmuration of Resolution and Appeals. It is my great pleasure to introduce the musicians here today. Faradena Afifi, Steve Beresford, Ansuman Biswas, Bettina Schroeder, with the The Noisy People's Improvising Orchestra and Maggie Nicols. This event is very much a process of recitation and revisiting and reinterpreting passages from resolutions and appeals distributed by the Women's International Democratic Federation between its founding congress in Paris in November 1945 to the Conference of Asia in Beijing in December 1949 and the World Congress of Women in Moscow, June 1963.

“In late November 1945, when the Women’s International Democratic Federation emerged from the ashes of World War II on principles of world peace, women’s rights, democracy, anti-fascism, and children’s welfare, 850 participants from forty countries attended its first gathering in Paris, France. Joining WIDF was an organizational, not an individual act, and the list of attendees provides women’s names, their country of origin, and their organizational affiliation. Participants were not all communist-linked mass organizations. In fact, many of them were more ideologically jumbled, including those that emerged from the call for women’s unified activism against fascism. Four women from India attended their founding Congress, including Ela Reid from MARS. One of them, Vidya Munsi, traveled to Paris directly after the conference of the World Federation of Democratic Youth, another communist-linked mass organization that was held in London the month before. “Over 15,000 women filled the Velodrome D’Hiver (Winter Stadium) to capacity,” remembered Munsi of the founding address by French resistance leader Eugenie Cotton, who led the international women’s organization from 1945 to 1967.

In 1945, WIDF was the only transnational women’s organization that explicitly condemned colonialism and demanded international solidarity for liberation struggles. Its founding document stated: “The Congress calls on all democratic women’s organizations of all countries to help the women of the colonial and dependent countries in their fight for economic and political rights.” Activists from Vietnam and India in particular, but also the United States and Egypt, deepened WIDF’s opening commitments both theoretically and politically. They pushed delegates to define fascism in relationship to imperialism. They described fascism and its racialized genocide as one powerful force behind military conflict. They argued that colonial occupation and anti-black violence were other forms of fascistic violence that crushed the freedom of people around the world. Ela Reid, Jaikishore Handoo, Duong The Hauh, and other delegates made arguments powerful enough to shift the position of delegations like the one from Algeria, in 1945 made up primarily of French-origin, mostly communist members who lived in North Africa.

Duong The Hauh, an expatriate from Vietnam who lived in France, tethered anti-fascism to anti-colonialism. She radically decentered Europe by naming another inside/outside contradiction laid bare during the war.

"Mothers and spouses from Europe, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Russia, France, you who suffered the atrocities committed by the bloodthirsty brutes of Nazism, you who lived next to the crematoriums in Belsen and Maidanek, you learned how far human cruelty can go when an odious regime allows a group of declassed, ambitious, predatory men to indulge freely and entirely into their wild beasts’ instincts.

And if the bloodiest drama could unfold this way in Europe, if the most cruel and barbarous actions could be committed by the most civilized countries of the globe, it is because even before this war, even during peacetime, this barbarity already existed there at a latent state, it has always existed, in real and permanent ways in the colonies.

We are, us Indochinese, a colonized people for eighty years. We have been knowing for eighty years a perpetual regime of occupation, oppression, police terror, that reduces human beings to the level of a beast."

Duong The Hauh reminded her audience that inside Europe, anti-Semitism drove the horror of mass incarceration and the murder of Jewish and also Roma people as racialized, religious threats to a homogenous white Christian Europe. Outside Europe, she argued, colonialism was a racialized system of expropriation of land, lives, and resources; as such, it preceded the anti-Semitic holocaust of the mid-twentieth century. “Civilization” references Europe’s self-image as well as its fig-leaf rationalization of colonial occupation, extraction of resources, and monopoly over the markets of non-Europe. For Duong The Hauh, the barbarous civilization inside Europe had been integral to its colonial occupations outside Europe for decades, for centuries. Any anti-fascism that was truly integral to women’s internationalism must know its history and take stock of its roots. Colonialism was Europe’s exterior face of imperialist civilization/barbarity, she argued, and could not possibly remain on the margins of women’s internationalism any longer.”

Excerpt from Bury the Corpse of Colonialism, Elisabeth B. Armstrong

The Otolith Group in conversation with Elisabeth Armstrong & Dubravka Sekulić

at greengrassi, Lonodn, in the context of the exhibition We will move to the land of birds as a flock of previous humans, January 27, 2024.

Ariella Azoulay and the understanding of photography as transit visas "we are citizens not of nations but of images"

the panorama ends where Otolith 1 begins, in 1963 >>>

this incredible podcast with Elisabeth Armstrong on Millenials are killing Capitalism

And as I was working with the All India Democratic Women's Association, they were saying 'how can we not go to the UN in 1995 and not critique structural adjustments, not critique neoliberalism, not critique the way that we are being forced by the global north to consume ourselves under their agenda of extraction, of global extraction.'

One of the things I absolutely love about this exhibit is that not only the love, the friendship, the intimacy is here, but also the arguments. The argument was: who do we want as representative Indian women? Well the U.S. had said this is by 1987, starting in 1945, by 1947 the U.S. said: if you associate with the WIDF you are not a friend of ours. And the thousands upon millions of women who joined precisely because they did not want to be the friend of the U.S. government, that is the story of the WIDF (The Women's International Democratic Federation).

Tito, travelling, and non-aligned movement ... but these women did this already twenty years earlier !

Other women from other countries were barred from attending. Charlotta Bass, an African American civil rights activist and journalist, was denied a passport by the US government. Wei The, the overseas Chinese delegate from Thailand, described similar intransigence: “three more delegates who have prepared to attend this momentous conference, but owing to the various obstructions by the Songgram reactionary government (in Thailand), they have been delayed and are still on the way, unable to attend the Conference.” The only delegate from the Philippines had been living in China for decades. In 1948, the US-backed government had crushed the communist and workers’ struggle of the Hukbalahap Rebellion on the island of Luzon. The US had also made sure their grip around Filipinos’ travel to and from the islands was tightened so no dissidents to American-backed rule left or entered the country. For the Japanese delegation, only Tanaga Hamaku, a Japanese revolutionary woman living in China, could attend. She represented the large delegation from Japan who were forbidden to attend the conference by MacArthur’s occupying government in Japan. Scholar Mire Koikari describes the letters between Song Qingling, an important, if largely symbolic leader in the All-China Democratic Women’s Council. In protest of their visa denials, the Japanese activists held a parallel Asian Women’s Conference in Tokyo on December 16 and 17, 1949. Song’s letters to Miyamoto described the conference in Beijing in ebullient terms. “All shared the will to oppose imperialist wars, bring eternal peace to the world, and emancipate colonized populations.”

Excerpt from Bury the Corpse of Colonialism, Elisabeth B. Armstrong, page 58

Soong Ching-ling, who had close ties to the Japanese Women's organization was in constant contact ...

Japanese Women's Fight for Equal Rights: Feminism and the US Occupation of Japan, 1945 - 1952. >>> Thesis by Jessica Pena

In their train compartment on the Vladivostok Express, there were only a couple of hooks, so Lillah, Hanna, and Rie kept their clothes packed in their suitcases tucked under the bottom berth. The train was too cold to take off their coats much anyway, and spare hooks were not the issue in the end. They settled themselves for a long journey. Some played dominoes and other games to pass the time. Like everyone going to the conference, they talked with each other and shared explanations of their lives and struggles with the other second-class compartment delegates traveling to the Asian Women’s Conference.

Two conversations among many: Gisele Rabesahala from Madagascar packed a cabin one evening with her stories of their struggles against the French. Gisele could hold her own in any space: she was a founder of the communist Congress Party for the Independence of Madagascar. Two years earlier she led the Malagasy Solidarity Committee to demand the release of ninety thousand political prisoners who had been accused of leading a rebellion against the French occupation. She described the old colonial tactics of warfare, pitting Senegalese and Sudanese soldiers against them, since according to French colonial logics, “you can’t trust the Madagascar soldiers to subdue their own.” But divide and conquer was powerful within the country as well, she said: those who lived on the plateau of the island were pitted against the people of the lowlands, by the French and the powerful. Even nationalism on the island, that sense of unity within a country of different religions, cultures, and dialects, had to be created as a whole cloth. She described how after the war ended in Europe, French terror in Madagascar had only increased, and now she was forced to live and organize wholly underground.

Ding Ling, the famous Chinese author, described the revolutionary tactics that had won over the Chinese masses, overwhelmingly farmers. “Rely on the poor peasants; Unite with the middle peasants; Isolate the rich peasants; Fight the landlords.” She had worked in the liberated areas for many years, and land reform was first, with land titles given to landless women as well as men. But even before, she said, “we Communists had to make lower rent, lower taxes, and land reform. . . . [S]eventy five percent of “the peasants’ income went to landlords. Tenants had to provide fertilizer, seeds, labor; landlords only provided land. At harvest time tenants must give half and best of their crop to the landlord. When peasants can’t pay, they go into debt at enormous interest rates which accumulate more debt.” Alongside land reform, their Chinese cadre fought for universal education for girls and boys, men and women, and for local systems of representation with universal rights to vote.

The delegates from Lebanon and Syria, Salma Boummi, Amine Araf Hasan, and Victoria Helou were close, like Lillah was with Hanna and Rie. Like her circle, they came from Muslim and Christian religious cultures, but shared a passion for women’s rights and a hatred of colonial occupation. But they all had children, families, and lives rich beyond their activism alone. Mahine Faroqi, from Iran, was young like Lillah, and she also had no children. The communist Tudeh Party in Iran was underground again, banned by the Shah’s regime. Only a year before, Iran’s most well-known activist for women’s liberation, Maryam Firouz, had joined WIDF’s Congress of Women in Budapest with her fiery speeches and sharp demands for anti-imperialist solidarity from the American delegates in particular. In the words of Firouz: “Let the American people know that their representatives order mass imprisonment, massacres and tortures. Tell your people that, supported and strengthened by American imperialism, the reactionaries in Iran crushed the young peoples’ movement of Azerbaijan.” Her notoriety to the Shah’s government meant leaving the country was out of the question in 1949. Mahine Faroqi was young, less well-known to the police than Firouz, and managed to gain a visa to travel to Moscow.

Excerpt From, Bury the Corpse of Colonialism, Elisabeth B. Armstrong, page 47-49

So those who were able to come .... they were walking to the conference. ... A whole group of women came from Moscow, they took the train together -- and one of them was the writer Ding Ling

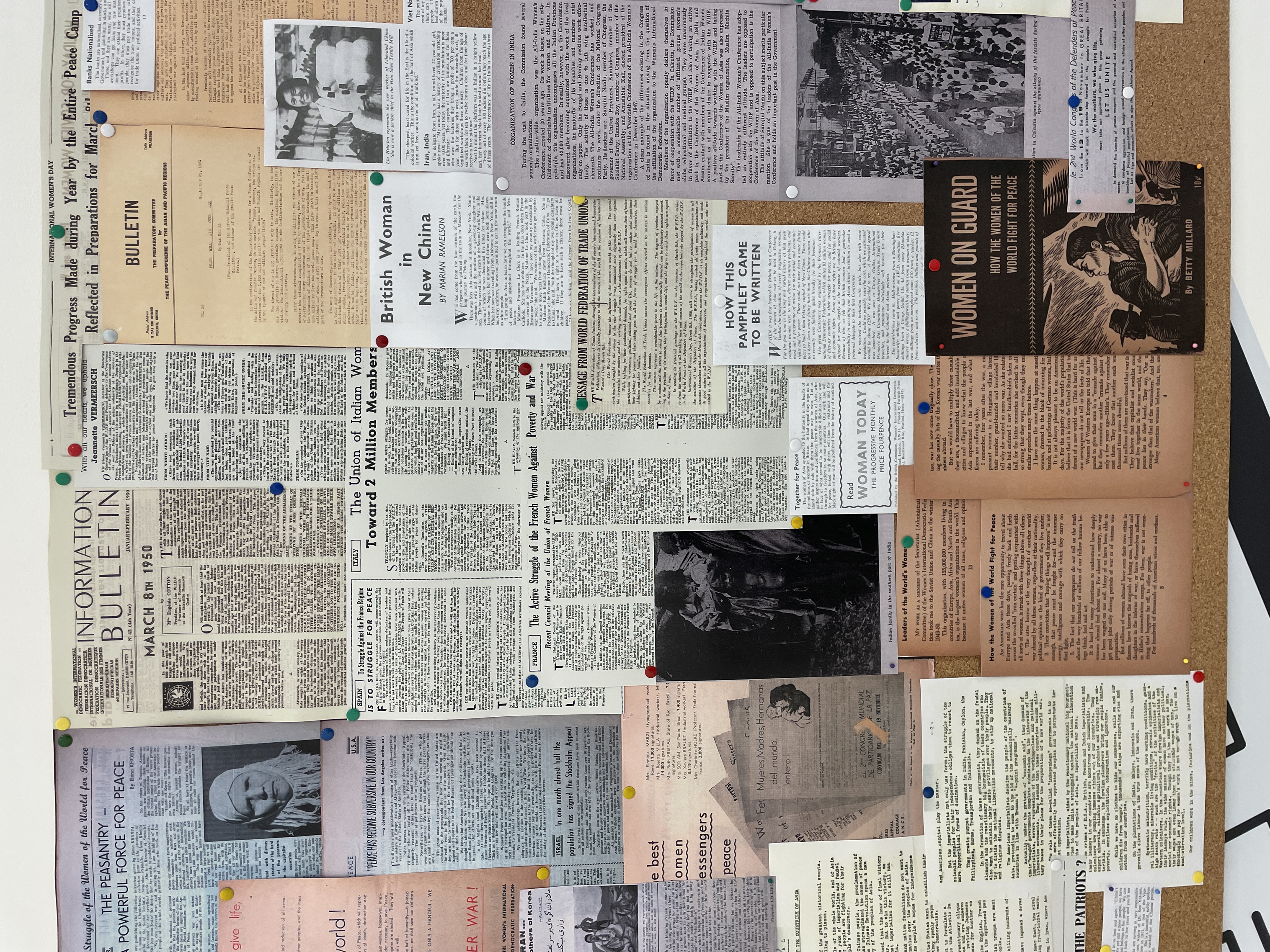

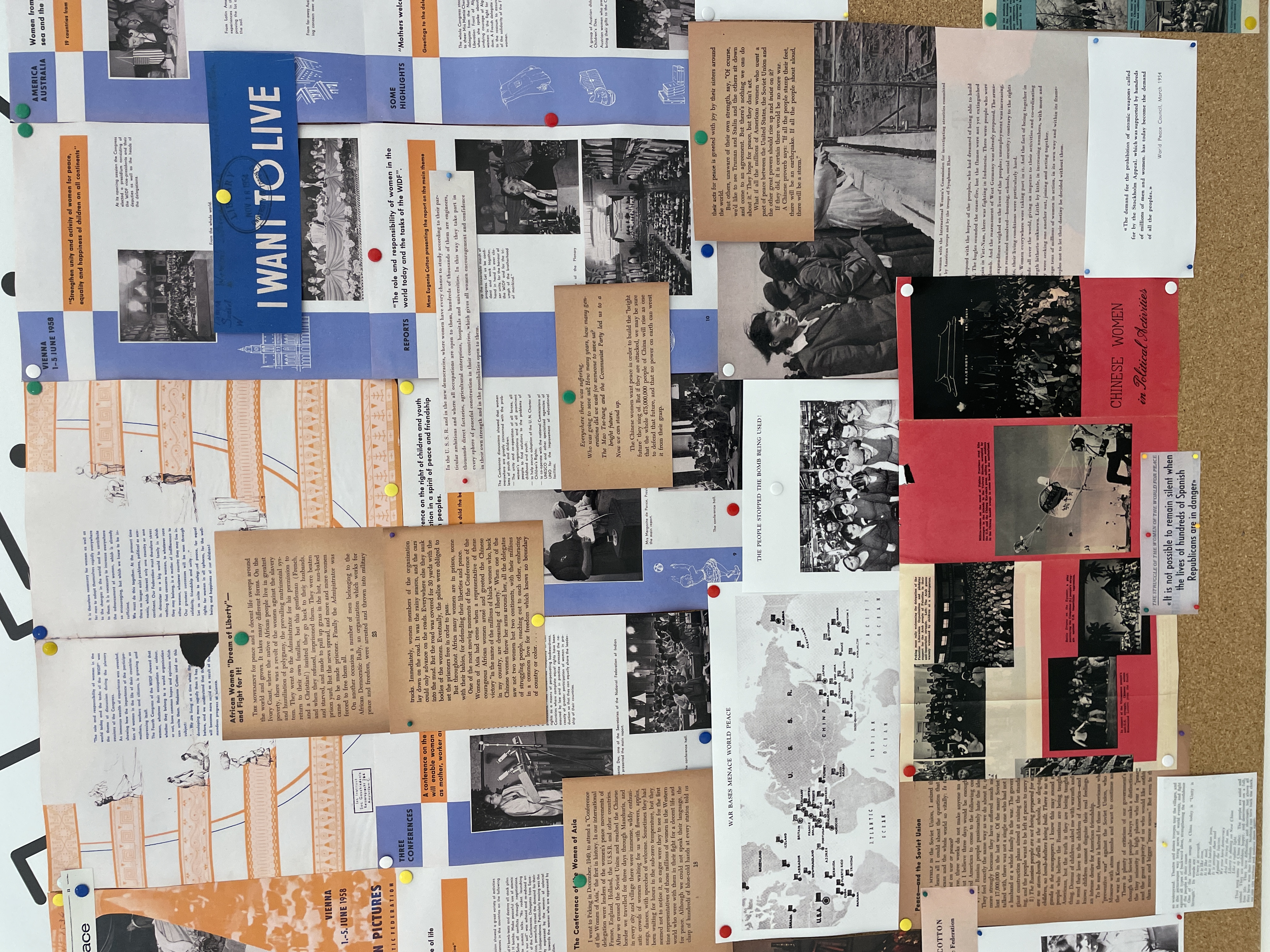

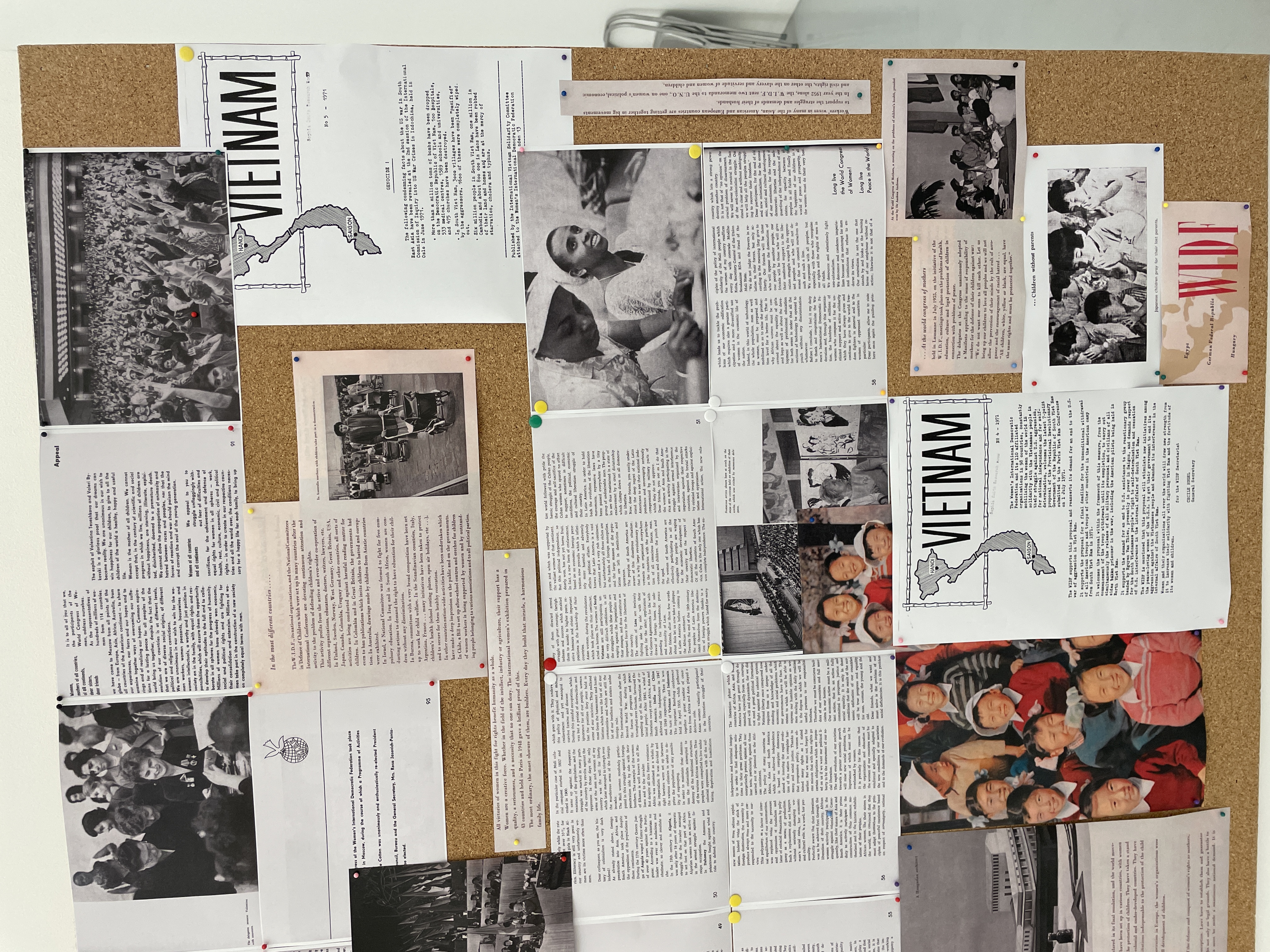

... the means of political reproduction ... the pamphlets, posters, texts, statements, illustrations, photographs, maps, charts ...

Note: How to work out the intertemporal relation: Working on questions -- questioning other moments in time through questions of our time ... who brings what kind of interest, leading to which questions ... the interest stretches and travels the intertemporal

Information Bulletin, Madame Eugénie Cotton, March 8, 1950.

in this year of 1950, when each day brings us still more terrifying perspectives on what a new war would mean, International Women's Day must be for women and mothers throughout the world of all opinions and beliefs the occasion to cry aloud.....

The question becomes for us, in the present, how to re-narrate the techniques of coordination between our time and that time. How to work out the intertemporal relation between that moment——let's say the political sequence between 1945 and 1963 that we are mapping here in the panorama——and our moment. So our relation to 1945 and 1963. And that requires building a certain apparatus that can sensitise us to the kinds of knowledge that is becoming available. And that's kind of how we try to approach the printed matter.

visibility and audability --- to listen to the mulitiple voices, listening to the arguments, the disagreements, listening -- the knowledge produced in and through the movement building and how to build an apparatus for hearing that knowledge

it's not about declarations, but about developing a method of self articulation through the knowledge production and claiming that...

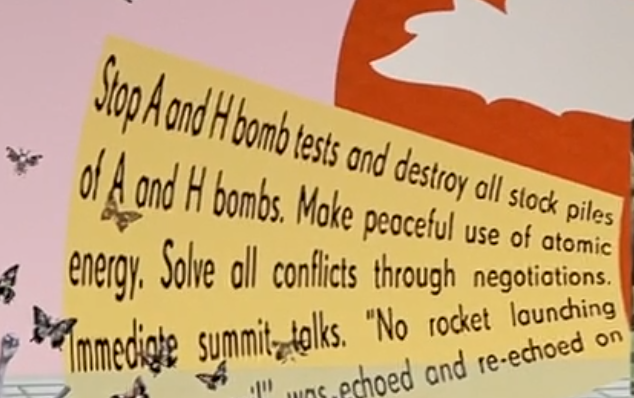

I want to live! Ban atomic weapons!

I want to live! Ban atomic weapons!

I want to live! Ban atomic weapons!

I want to live! Ban atomic weapons!

I want to live! Ban atomic weapons!

narrating a panorama .... emerging from various different time-zones, chronology is impossible ... the chaos of internationalism and what communism could mean in South Asia ....

a more challenging kind of unity -- one of the fights the pull something out: the notion of motherhood for example .... that language of anti-imperialism will kill us ... Lillah Suripno ... motherhood in its complexity and impossibiliy

Claudia Jones: The Struggle for Peace in the United States in Political Affairs, Feb 1952.

Claudia Jones against the Korean War on Black Perspectives

this is a location of struggle, we must find out what we don't know, what is it that we don't know enough about -- and they used a technique --- Claudia Jones and her speech on the Korean War in 1952 --- a demand for just peace is precisely a demand that is refused, a demand that is asking too much -- how they build the knowledge around what they tried to achieve –– Suzy Kim -- fight for definitions

the necessity to fight for definitions .... the meaning of propaganda ... various notions: permanent political persuasion ... propaganda as method of hearing disputation, a method of tuning in ....

how do these women matter --- to see what's missing, to hold the lacunae, or to imagine what might come to be, maybe another way, in what dialogs are we part of, that we haven't known to see, what echoes..... that complicated calibration of what can be said

One major way by which the women’s movement of the transnational left maintained ties across the world was through the pages of the women’s press. The WIDF periodical Women of the Whole World began publication in 1951 in five languages—English, German, French, Russian, and Spanish—with an Arabic edition added in the 1960s. While other similarly large international women’s organizations had published bulletins and newsletters, none compares to the scope and reach of Women of the Whole World. It tried to provide geographical coverage of women’s issues in every continent, with debates about local problems, biographies of well-known women, histories of women’s movements throughout the world, and topical articles on global politics as related to women’s rights, children’s welfare, and peace. The cultures section included introductions to films, fashion, and cuisine, with recipes from various countries and regions.

In designing the publication, the editorial board explicitly challenged mainstream women’s magazines, which more often than not appealed to “glamour, romance, luxury,” as a contributing writer from the United Kingdom sharply criticized in a passage worth quoting at length for its continued relevance:

“What is the approach of such magazines? What do they tell the women? First and foremost, they falsify life. The problems of women in Great Britain today, the unremitting struggle to feed their families, with the cost of living continually rising, their anxiety about war, the difficulties of young couples without a home to live in—such problems are either ignored completely (as in the case of the women’s desire for peace) or surrounded with sentimentality. Glamour, romance, luxury, “love”— these are the stock-in-trade of the women’s magazine: How to make oneself beautiful (with tactful references to the cosmetics advertised in the same issue); how to be attractive to men; how to win a man’s love; how to keep it when you have got it. Along with this line of approach go, inevitably, reactionary ideas about the status of women: all women want, or ought to want is a husband, home and children; equality and independence are a myth; women are not capable of being more than second-rate in any achievement outside the home; in the marriage relationship, man must be the master; women are emotional and not rational beings, because of their biological make-up. These magazines receive the support they do from the women because they supply vicariously (and in a cheap and falsified way) the colour, adventure and change which the women lack in real life. They provide a dream world into which the women can escape for an hour or so, and in so doing skillfully divert their minds from the possibility of solving their problems, and sap the confidence of the women in their own abilities and consequently, in their capacity to change things.”

the question of de-individualisation is important insofar as we try to imagine groups, flocks, crowds, the supernumery, the multitude, try to imagine more than one....

To address such problems of the women’s press, the WIDF called a meeting of editors of women’s magazines between April 27 and 29, 1954, at its offices in Berlin. From the ninety-nine magazines of thirty-nine countries published or supported by organizations affiliated with the WIDF, thirty-five representatives from twenty-two countries took part in the meeting. WIDF president Eugénie Cotton underscored the important educational role of the press to show how Indochina, Korea, and Europe are interdependent, so that what is going on beyond one’s own borders “are not local problems” but “closely connected and the way in which they are solved can unleash a world war or guarantee peace to all,” warning that “too many women still think it is not their business to bother about world events.” The editors at the meeting agreed on the need to reach a broad readership and hailed their “great victory” in creating magazines “for the first time in history, that know how to talk to average women about the social and political events which have been changing the face of the world; magazines of current interest which break through the charmed circle of dreams and plunge women into the thick of events; it is a bit gain which we much go on and on consolidating.” To counter the “enormous circulation of the ‘heart-throb’ press” in societies where women have few options but to marry for “economic emancipation,” the editors called for their own magazines to devote sufficient space to stories, serial novels, and advice columns that women seek in order to provide “a new moral world” of family and gender relations, claiming that “it is wrong to think that these matters are not political and do not help women.” Pointing out the importance of practical content dealing with “household matters, needle work, fashions, and articles on medical and educational questions, “leftist women already in the early 1950s grasped onto the powerful argument that the personal is political, well before it became the rallying cry of “second wave” feminism. Affirming the need to expand the readership beyond housewives in the cities who made up the bulk of the current audience, WIDF secretary-general Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier urged the magazines “to make a special and consistent effort in the direction of women workers, industrial and office workers, etc., especially at factory gates; and also to make a very very great effort—because here our weakness is graver still—in the direction of peasant women subscribers in the countryside.”

Successful with their own publications, Italian and French women shared suggestions on how to improve Women of the Whole World from their experiences with Noi Donne and Femmes Françaises. They increased circulation by going “door to door, in the factories, in the offices and in the countryside” to make the magazine the basis for shared cultural activities, recreation, and solidarity actions. As a result, the women could proudly claim that “our press is a powerful element of unity; its circulation is one of the most effective instruments of organization. It makes it possible to set up new local groups, to keep up permanent contacts with women; it introduces into the homes ideas of peace and progress, the consciousness of a new dignity, and confidence in a future of real happiness, won by determination and a common fight.” Noi Donne’s editor Grazia Cesarini boasted of her magazine, published in color with an impressive circulation of three hundred thousand, distributed by some fifteen thousand canvassers throughout Italy, the best of whom would be presented awards by the Union of Italian Women. Received with more enthusiasm than beauty contests, the awards were organized explicitly against “one beauty contest after another, where Miss This and Miss That, allegedly ‘ideal’ girls, are chosen but which are actually a glorification of sex or of the false idea of an artificial feminine type with no great aspirations who is satisfied to be nothing but an obedient wife.” Dismissing such beauty pageants in which women are judged by their looks, the Union of Italian Women chose eleven women “with their great qualities, which are both traditional and new,” to be publicly honored for the first time in Italy: a professor of psychology, a primary school teacher, a widowed peasant manager of a farm with seven children, a worker fighting for equal pay, a member of the solidarity committee and the women’s auxiliary of the dockers’ union, a factory manager, a doctor, a physicist, a midwife, a caretaker of the homeless, and a writer.

Excerpts from Among Women around the World—North Korea in the Global Cold War, Suzy Kim, page 17-20.

a kind of humility to listen ... we want the answers, but maybe the answers are here for us to hear rather than to know .... the combination of curage and humility alongside the knowledge of a collective project ....

Presidential speech at the The National Federation of Indian Women, 1959

The National Federation of Indian women is happy to have its Third Conference at Banaras, the place where millions have been coming during many centuries to find Peace. We have had our Conference at Delhi, Calcutta, Vijayawada and now we meet here.

The National Federation is now five years old and looking back on these years we see the results of our efforts to awaken the women to their rights, towards the security of the children and for peace.

Since the Vijayawada Conference many important bills affecting the position of women were introduced in Parliament. For example, the Hindu Marriage Bill, which made polygamy illegal and divorce possible for the Hindu woman, gave the women of India a better position socially, economically and politically. The Hindu Woman’s Right of Succession Act which gives the right to daughters to inherit their fathers’ property equally with the son, is also another step in the right direction because, though it may not be very effective when implemented, it gives a better position to the daughter and the wife. The Anti-Dowry bill, which is on the anvil of the House of Parliament has the support of thousands of women in India—women who have begun to understand how the shackles of bad social customs are keeping them from taking their proper place of responsibility in society and in the country. Schools and playgrounds for children have been the demand of many branches of the National Federation of Indian Women and in many instances they themselves have started or helped in starting such centres.

(…) The main task has been, however, to make the women aware that all the legal and political rights which are given to us will be of very little use if there is no social awakening among the women. Because of illiteracy, superstition and traditional backwardness, which gave the women an inferior place in our society, a large number of women cannot take advantage of their legal and political rights. Our practical efforts to meet the situation have been the starting of adult literacy classes, co-operative and handicraft centres at several places, which give the women some means of adding to their family income, as well as a wider knowledge of their rights, and responsibilities.

Our members come from all strata of society. We have among us workers from the Darjeeling tea estates, peasant women from the Punjab, mine workers from Bihar, and women teachers, doctors; we have also those who are serving the people as elected representatives in Municipal Councils, State Assemblies and the Parliament.

It is the task of the women’s organizations to do the spade work and we feel proud to acknowledge the efforts of our workers in the urban and rural areas. These efforts are necessarily on a small scale and many of our workers feel hesitant even to send us reports of their work but we want to remind them that every effort, however, small, towards the right direction counts and will prove like leaven in the bread in awakening our women.

We have also tried to bring together the various women's organizations for specific problems and we think it is extremely important for women of different religions and political parties to get together and shoulder the stupendous task of solving the problems of poverty, illiteracy and ignorance in our country.

Our women have helped to collect funds, clothes and arid medicines in times of stress.

The latest instance was the floods in Kashmere. As India is a part of the world it has been our effort to keep our members well informed on what is happening in the world. The lessening of tension of the cold war and the hope of disarmaments, which means that the money spent on armaments today can be spent on building more schools for the children, more playgrounds and hospitals has been hailed by the N.F.I.W.

We have many more tasks ahead of us and much remains yet to be done. It is with an awareness of this fact that I recount the few things we have tried to do and have done successfully. I sincerely hope that at our next Conference we shall be able to count more achievements in our efforts to build up a sane world, free from the fear of strike and war, with the hopes of happiness for the future generations.

when I blasted off in my cosmic ship

I knew that the world congress of women

would soon be opening in Moscow

the flight program followed a strict timetable

and I had little spare time

Women from all countries of the world

you came by ship, by train, by air

you travelled great distances

spending many hours

sometimes days on the journey

and it was not only distance you had to cope with

many of you had to deal with police obstacles

never letting them get to you

and you had to deal with the fear of being shot

but you had to release obstacles

nevertheless you're here

and that is very good my friends

my cosmic ship

made one complete circle

around the globe in 88 minutes

in less than an hour and a half

I flew all over the continents

from the countries which sent their delegates to Moscow

to the congress of women

as I flew the thought came to me

how good it would be if my Vostok 6

a feminine spaceship so to speak

could throw a bridge

invisible yet strong from heart to heart

linking all the women of the world

I looked at our beautiful earth

never, I thought, never must this earth

so blue and glowing

be blackened by atomic ash

every hour and a half the dawn met me

the sun rose to an incomparable splendor of glowing colour

can we allow this sun to be darkened

for the people of our earth

by black clouds of nuclear war explosions

women of Africa

how beautiful your land is

seen from space

it truly bears the form of a heart

the burning heart of fighters

for freedom and independence

women of Europe

how lovely are the constellations

of your sittings at night

women of Asia

how majestic are the snow-capped peaks of your mountains

how lovely are your green valleys

how mighty deserts waiting for the labour of man

how beautiful are the mountains

how majestic are the mountains

how majestic are the mountains

deserts waiting for the labour of man

to transform them into flowering gardens

women of the Americas

how great and widely varied is your continent

stretching from the north to the south polar regions

my friends

all of you sitting in this hall

from whatever land you come

my terrestrial sisters from whatever continent

when flying over your countries

I delighted in the beauty of each

and know that in all of them

thousands, millions of hearts throng

with a longing for peace and progress

peace and progress

how good it is to stand on this lofty rostrum

and see all of you together

discussing the burning question

of how to rid our planet of the threat of nuclear war

how to make all peoples

independent, free and happy

how good it is

how good it is

how good it is

how good it is

another thing I want to say

when I looked at our earth

I thought of my mother

please do not be offended

those of you who are mothers

if I say as a loving and grateful daughter

that my mother really is the best in the world

from the bottom of my heart

I wish the women's congress successful work

and a good unity of hearts and hands

for the sake of peace, happiness and prosperity

for all the peoples of this earth

peace, happiness and prosperity

for all the peoples of this earth

peace, happiness and prosperity

for all the peoples of this earth

peace, happiness and prosperity

for all the peoples of this earth

peace, happiness and prosperity

for all the peoples of this earth

Thank you.

I'm going to do a, I mean, as you will notice, it's quite an interesting acoustic.

And obviously with a lot of people that will be even more interesting.

I'd like to be able to speak without this, but maybe I better, let me just see.

So it's hard to hear voices sometimes without the mic.

Oh yeah, that might be it.

Message to the women of the world

Hortensia Bussi De Allende, October 1973

I am addressing all the women of the world,

not to speak of my own tragedy,

nor my family and how we escaped the bombing,

nor the dramatic situation leading to our escape from Chile.

This message is to denounce the violence against a people

known for its long history of justice and democracy,

which is today the victim of the most vicious

and inhuman repression by the military junta.

there are no wrong notes,

you cannot sing a wrong note, it's literally, and again I hate keeping repeating myself,

but repetition's okay because sometimes repetition, I like that there's no such thing really

because it's always slightly different.

But you don't go up to the river and say "you're out of tune",

you just never do, you never tell nature it's out of tune, why do we have this thing, you know.

It'd be different if it's a composer and they want a specific thing, you sign up for that,

that's different, but this is expanding our understanding of harmony,

everything is in tune and everything is in time, in rhythm, again squirrels,

the way they move, they don't go one, two, three, four, they go.

But anyway we're doing the sustained piece now.

So let's just try, hey...

... becoming the noisy people's improvising orchestra ....