Chapter III: Fingering Charts

By 1785, five-key clarinets were commonly used in France, England, and Austria. Fingering charts and illustrations of the five-key clarinet first appeared in the literature in The Clarinet Instructor, published in London circa 1772, and shortly after, in Amand Vanderhagen’s Méthode nouvelle et raisonnée pour la clarinette, published in Paris in 1785. Charts for the five-key clarinet appeared in most clarinet methods until the second decade of the nineteenth century.

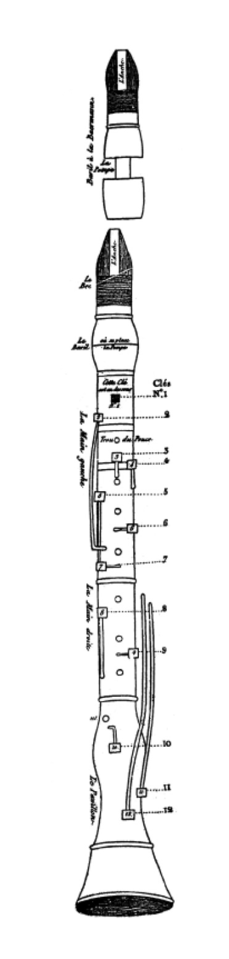

When examining fingering charts, it’s also interesting to notice the clarinet illustration, as a lot of information can be unfolded by it, like the reed position. However, we should always take these illustrations with a grain of salt since they are not always the most reliable source and presentation of the instrument played by the author at the time of publishing, and in extreme cases, the illustration barely resembles a normal clarinet.

The illustration in Vanderhagen’s 1785 book is one of these unfortunate cases where the finger chart shows a very odd illustration of the clarinet; The proportions of the lower half are off, the E♭ key is placed in a non-practical and unapproachable position, and the two upper keys are not mounted and misplaced.1

Apart from this, the fingering charts in this edition are quite standard. Vanderhagen provided two charts, one for diatonic notes and another for chromatic notes. He also included a short paragraph explaining how to read the chart. The range covers just over three octaves from the lowest note – e – to a’’’. Most fingering charts up to this point ascended to f’’’ or g’’’. He also provides three alternative fingerings to d’’’.

The chromatic chart ascends to e♭’’’. While Vanderhagen provides one fingering to most enharmonic notes, he clearly distinguished between a♭’, and g♯’, giving them two different fingerings. I found that this is quite unique, as most of the finger charts I examined showed only one fingering, and made no distinction between a♭’ and g♯’. The only two exceptions are the charts from Fredric Blasius’ Nouvelle Method de clarinette (1796) and Michel Yost’s Methode de Clarinette (1800).2 It is plausible that the latter two writers based their charts on Vanderhagen’s, considering the high reputation and success of his Méthode Nouvelle et Raisonnée pour La Clarinette (1785).3

After trying the two options, and mixing them up – using his g♯’ fingering to play a♭’ and vice-versa, I found that each has a distinct color and the slightest pitch difference. His suggestion for g♯’ is brighter, clearer, and very slightly higher in pitch compared to the a♭’ fingering, which is darker, lower in pitch, and the tone is less centered. These differences were applicable to the three different instruments I tested.

Although the finger charts from his 1785 book are the basis for the ones in the next method, there are several differences worth highlighting. While the range of the diatonic chart remains the same (e-a’’’), the range of the chromatic chart is extended to f♯’’’. In addition, the chromatic chart offers alternative fingerings to c♯’’’/d♭’’’, with a short paragraph clarifying in which circumstances each would be preferable. Moreover, there are also suggestions to open the F♯ /C♯ key to slightly adjust the pitch of f♯’/g♭’, and similarly open the A♭/E♭ key to correct the g♯’/a♭’. These small things suggest a more advanced approach.

Furthermore, Vanderhagen slightly changes his suggested fingerings for both g♯’ and a♭’, removing the addition of the left-hand middle finger from both. I believe that it depends upon the player and the instrument whether or not closing the LH second tone hole is necessary.

Lastly, in this 1799 edition, Vanderhagen also writes shortly about the numbering of the keys, counting them from the bottom to the top. Thus, the lowest key on the instrument (closing the bottom tone-hole), the E/B key is key No. 1, F♯/C♯ key is No. 2, A♭/E♭ key is No. 3, the A key is No. 4, and the speaker key (in the back) is No. 5.

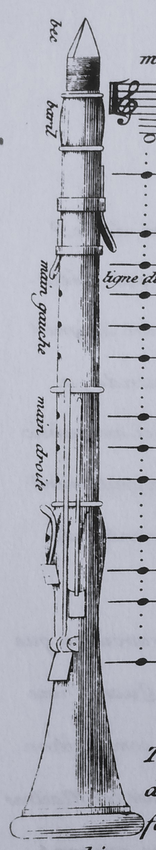

In his final method from 1819, the finger chart is significantly different for a couple of reasons. First, it illustrates and demonstrated the fingerings for the twelve-key clarinet, unlike the previous methods that showed the five-key clarinet. Secondly, his numbering of the keys is completely different from his previous book. In the 1799 method, Vanderhagen numbers the keys starting from the bottom keys, hence, the low notes of the instrument. In this method, he strangely chose to number them from the top of the instrument, numbering the speaker key in the back No. 1.

In addition, he only provided one chart for both diatonic and chromatic notes, making the distinction between them by writing the diatonic notes as half-notes, and the chromatic ones as quarter-notes.

In Article 2 of the 1819 method, the writer explains how to operate each key, using which finger.

The fingering chart covers a wider range, ascending up to c’’’’. This reflects the growing use of the top register of the instrument, as reflected in Louis Spohr’s clarinet concertos, for example.4 Finger charts that go up to high C started to appear in the wake of the nineteenth century, with Léfevre and Backofen being the first two.

Vanderhagen makes an odd mistake in his 1819 book when it comes to his instructions regarding one of the keys; claiming that the B/F♯ key (No. 8, according to his numbering system) should be operated using the 2nd finger of the right hand. That is surely an error, as this key is operated by the right-hand pinky.

Finally, he added a paragraph describing the clarinet illustration, identifying it as Heinrich Baermann’s instrument as used while giving his massively successful concerts in Paris in 1818. This clarinet was a model made by the Parisian maker Jean-Jacques Baumann, which featured a divided barrel with a metal sleeve fitted in its center.5

After examining all the finger charts, I noticed that Vanderhagen did not supply his readers with trill charts. Because of the use of cross fingerings, in some cases, it is impossible to trill using the proper fingering, and an alternative is suggested. Some authors included a separate trill chart, while others included trill fingerings in the main chart. Vanderhagen did neither in his two earlier books. In the last one, however, he did include a trill section in the one finger chart provided, and also dedicated an article to discuss how to employ the new keys to achieve trills on previously “problematic” notes.

Example 3.1: Clarinet illustration from Vanderhagen's Méthode Nouvelle et Raisonnée pour La Clarinette. 1785.

Example 3.6: Clarinet by Jean-Jacques Baumann (Paris). c, 1815, made of boxwood and ivory, 12 keys mounted on posts, features a divided barrel (Jane Booth Collection)

Example 3.4: Clarinet by Michel Amlingue (Paris), c.1780, made of boxwood and ivory, 5-keys, integral stock-bell, ivory mouthpiece (Hoeprich collection)