Chapter VII: Articulation

The technique of articulating on the clarinet is heavily derived from the embouchure and the position in the reed. When played with the reed on top, tongue articulation is much harder to achieve, and consequently, chest articulation was a common technique. This technique allowed clear separation between notes but was also very limiting in fast articulated passages, as Roeser suggested in his 1764 treatise: “Many repeated semiquavers are not in use on the clarinet since the chest must substitute for the tonguing, because of the position of the reed which is under the palate of the mouth.”1

Another articulation technique used was the throat. Both Léfevre and Backofen disapproved of these techniques, naming drawbacks such as ungraceful appearance, and uneven-sounding articulation, and even claiming they compromise the player’s endurance, as their production is very tiring.

These two articulation techniques were common despite their disadvantages up until the first decades of the nineteenth century. Vanderhagen, however, showed a preference for tongue articulation early on, and consistently encouraged his readers to use the tongue to articulate throughout his three methods.

Vanderhagen's only comment concerning another type of articulation technique can be found in his first method:

"Another example: All are slurred; but in order to distinguish three-by-three, it is necessary to emphasize the first not by a small tongue stroke, but by a small expression of the throat, because in marking the first note too much by tonguing it compares to this: 2

Throughout his three methods, he talks highly of articulation as a manner of expression and compares tongue strokes to the movement of the bow in string instruments. In his 1819 treatise, he states:

"Tongue strokes are essential for expression; they are to wind instruments what the bow is to stringed instruments like violin, viola and bass. The fortepiano, the harp, the lyre or the guitar, in the absence of a bow, use a sensitive expression to attack and to make the first note of a song or of any passage be felt."

Thus, he suggests different syllables and strokes to produce a varied range of articulations from soft detaché to crisp staccato.

In his earliest book, he implies that when there is no indicated articulation over the note, one should pronounce it by voicing the letter “D”. This produced a soft detached articulation, while still maintaining the connection between the notes. Vanderhagen doesn’t consider the “D” articulation in the detached category, nor in the legato category. In the second edition, Vanderhagen changes the “D” stroke to “Tu”, which he calls a “legato stroke”, and in his last book, he omits the use of any syllable, and plainly describes this articulation as a “soft tongue stroke”, while emphasizing that the airflow should be continuous, and there must be no interruption in the sound.3

This type of articulation is omitted from other method books of the period, in which the writers simply make the distinction between detached articulation and continuous slur. For example, in his 1802 method, Jean-Xavier Lefèvre distinguishes between three different articulations: slurred (le coulé), detached or cut-off note (le detaché or le coupé) – which is marked by a small dagger above the note, and is articulated by a sharp tongue stroke - and the piqué - which is marked with a dot above the note, and is articulated with a lighter touch that the detaché and coupé. Interestingly, Lefèvre’s syllable of choice for all tongue articulations is “Tu” – Vanderhagen’s syllable of choice for the soft and neutral articulations.4

Regarding types of staccato, in his earliest method, Vanderhagen provides the letter “T” for any type of detached articulation, to be distinct from the soft “D”.

In his later edition (1799), he makes a different distinction between the “Tu”, to the staccato “Te”.

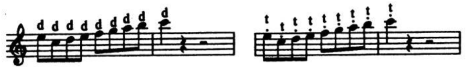

It is important to highlight a small contradiction regarding unmarked or unarticulated phrases; besides the statement that in the absence of written articulation, one should detach the notes with soft tonguing (“D”/”Tu”), Vanderhagen also implies that such phrases could be articulated freely, and even provides specific examples that could be used in the absence of written articulation instruction depending on the mood and tempo of the piece; Thus, for a moderato phrase, he suggests using “…the most beautiful and the most useful” combination of two slurred-two detached notes. He consistently shows a preference for this articulation in all three of his books. For Allegro phrases, he suggests slurring two-by-two, and for very fast tempos he recommends slurring over the entire measure.

In the latest book, nonetheless, Vanderhagen suggests that unarticulated phrases are where the artist can freely express his own musical ideas, good taste, and virtuosic abilities.5 This may indicate that perhaps in this last book he aimed to reach a wider range of students at different levels – from beginners learning the very basics of music and clarinet playing to more advanced, mature players who can make such artistic choices.

This observation about unarticulated phrases is in fact a fascinating combination of two different approaches; According to one approach, in the absence of articulation instructed by the composer, the performer should use a non-legato style of articulation. The other approach is more relevant to virtuosic solo performance style and encourages the performer to articulate as he finds fit according to the movement’s mood, and his own taste and abilities.6