Chapter VIII: Self-Expression, Embellishments, and Cadenzas

Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century and the first two decades of the nineteenth century, embellishments and cadenzas were among the most significant manners with which soloists could express their creativity, individuality, and virtuosity; making them an essential part of the performance, and of the audiences’ experience. Since this practice was vital to the performance practice of the period, many discussions developed around the topic of skillful use, good taste, and abuse. Composers, music critics, and educated listeners all agreed that a tasteful use of ornaments, from simple trills and turns to florid melodic alterations, could elevate the musical performance, and create a highly satisfying and touching effect. However, with the rising numbers of amateur musicians in the wake of the nineteenth century, and in the hands of unskilled, inexperienced musicians, inappropriate use of embellishments, long meaningless cadenzas, and wrong and excessive use of fiorituras became a true plague.

Thus, early nineteenth-century performers, on the one hand, became more restrained with their ornamentations, and composers, on the other hand, became more particular and specific in their instructions, and often wrote in the required embellishments and melodic alterations they wanted. Despite being undoubtedly aware of the changing approach to embellishments, Vanderhagen did not address, nor indicated any changes. Nevertheless, it is noticeable that in each edition he talks less about them, giving more concise descriptions, and fewer examples; In the first edition of the book he described each embellishment and its effect, and provided examples of a larger variety of embellishments: appoggiatura, accent, grace note, trill, and mordent. However, in the last one, he focused only on the trill, turn, and appoggiatura.

The Trill

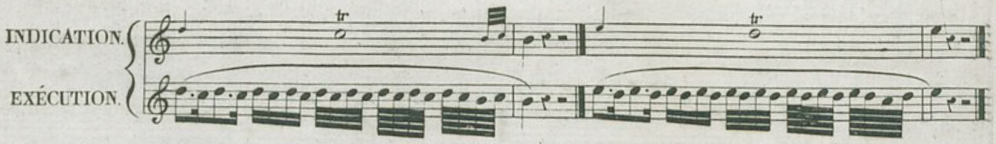

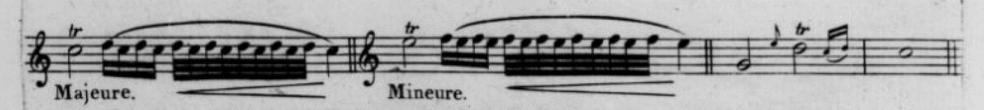

The trill - literally translates from French as “cadence” - is consistently described by Vanderhagen as a fast movement between the written note marked with tr or + , and the note located one diatonic step above. The trill should start at a moderate speed, and accelerate gradually as it goes before the resolution.

This definition and execution recommendation stays essentially the same in each of Vanderhagen’s methods. However, minor nuances can be observed:

In his earliest method, Vanderhagen specifically mentioned the “prepared trill” – a trill that starts with the upper auxiliary note on the beat.1 In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century many discussions surrounded the beginning of the trill, and while it was generally accepted in eighteenth-century performance practice to start the trill from above, some disputed the importance of it or strongly supported starting the trill from the main note. Nevertheless, in the wake of the nineteenth century as musical taste shifted into a more Romantic style of writing, trilling from the main note became common practice, particularly in the German school.2

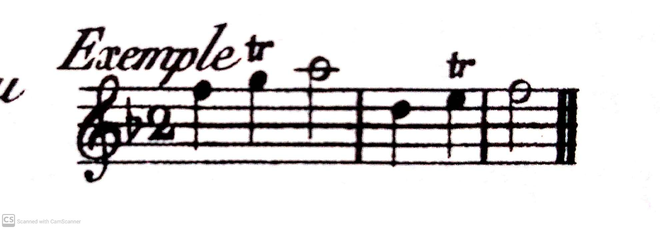

Vanderhagen did talk in his 1785 book about instances where the player does not start the trill from above, naming it “sudden” or “non-prepared” trill, which can be used in certain situations, as demonstrated in the following example (8.1).

Although it can be said that prepared trill would stay in use at least until c. 1810, and later in some cases depending on the composer’s style of composition, it seems that in the wake of the new century, performance practices were more flexible and diverse. This subtle nuance is evident in Vanderhagen’s second method book, published in 1799, where the writer didn’t mention the distinction between the two types of trills. He did, however, provide only examples where the trill is prepared. As Vanderhagen showed the tendency to stick to the performance practices and traditions of the second half of the eighteenth century throughout his life, this could mean that perhaps he objected to the matter of starting the trill on the main note in general.

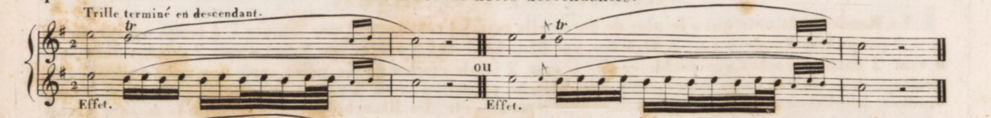

Apart from this, and unlike his earlier book, he suggests finishing the trill by adding a closing ornament, or turn, of “two small notes” before the resolution as demonstrated in example 8.2.3

Despite the changing taste regarding the execution of trills, methods for the clarinet written as late as the 1820s suggest that French school musicians stuck to the prepared trill well into the nineteenth century. For example, Vanderhagen himself included examples showing trills starting from above in his 1819 method, Nouvelle Méthode de Clarinette Moderne à Douze Clés (example 8.3).

Later examples include Iwan Müller’s clarinet method Anweisung zu der neuen Clarinette und der Clarinette-Alto, which was published in 1826 first in Leipzig, and then in Paris under the title Méthode Pour La Nouvelle Clarinette & Alto-Clarinette. Here, as in Vanderhagen’s book, Müller provided the following examples (8.4).

Another interesting example from French pedagogy in the second decade of the nineteenth century comes from Jean Carnaud’s Méthode pour la Clarinette written for the Müller thirteen-key clarinet. Carnaud’s view was more diverse and flexible, and according to the examples he provided, a trill could start from the main note or from above, depending on the composer’s demand (example 8.5).

The Turn

The turn, also known as Brisé or Grupetto. By Vanderhagen’s definition, “The turn of two notes borrows one from above and one from below the principle note and is therefore designated by “4 This definition, from his 1799 book, comes with two examples for execution (8.6, 8.7).

He reuses the last example in his last method, twenty years later. Interestingly, while this has been a common ornament through the eighteenth century, Vanderhagen did not mention it in his earliest edition.

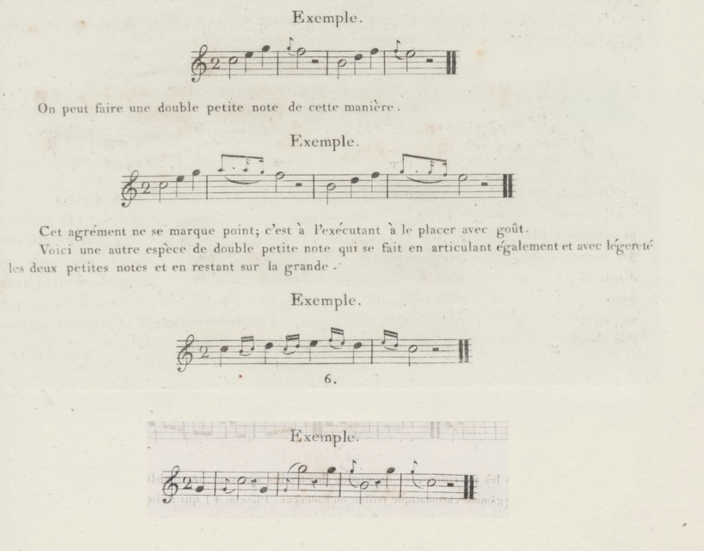

The Grace Note (notes de gout) and The Appoggiatura (port du voix)

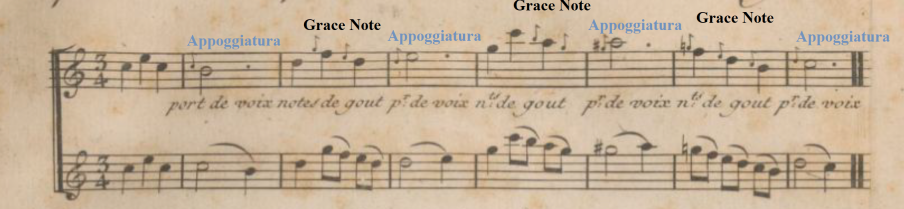

Vanderhagen defines a grace note as a “small note that is found before a principal note that serves to form a melody”. In his 1799 edition, he defined “grace note” and “appoggiatura” as two different ornaments, though similar. While the grace note was most commonly used to fill in between descending thirds, the appoggiatura, according to the author, is a “small note following another on the same pitch and it carries the sound of the pitch above or below it. The following example (8.8) from his 1799 Méthode Nouvelle pour La Clarinette demonstrates this concept.

In his two earliest methods, the writer speaks highly of the grace note, saying that it is the most tasteful embellishment. However, this comes with a disclaimer that one should only use it in solo pieces and passages. Never to be employed in orchestral tutti, or in any case where two instruments play the same melody.

Vanderhagen’s last method also highlights the grace note in the same manner, providing similar examples of the port du voix. This time, however, he added a comment regarding the execution of the ornament:

"Any small note flowing over one or more large notes flowing either by two, by three or by a greater quantity together, it is always necessary that the one which begins the flow, is expressed by a small inflection, in order to make the separation of slurred notes from unslurred ones clearly heard."5

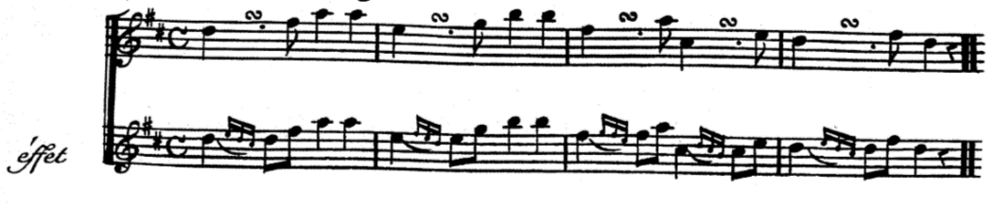

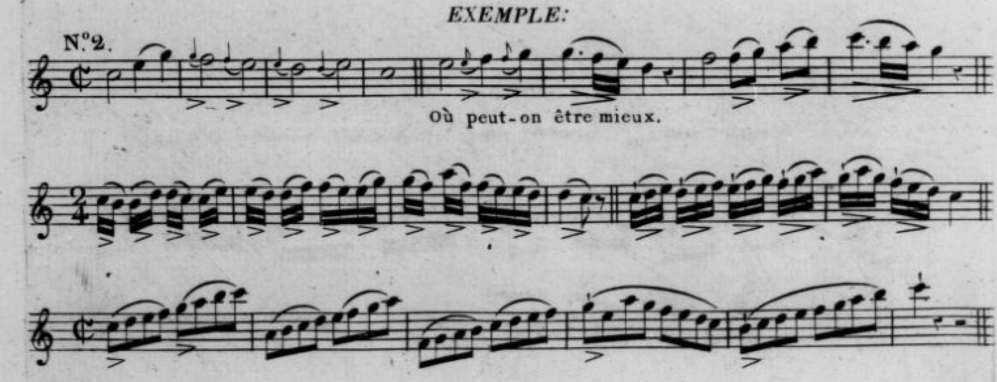

Meaning, when playing a grace note, or a passage of sixteen notes – for example – the first of every group should be slightly emphasized. This makes the articulation and expression clearer. As demonstrated in the following example (8.9)

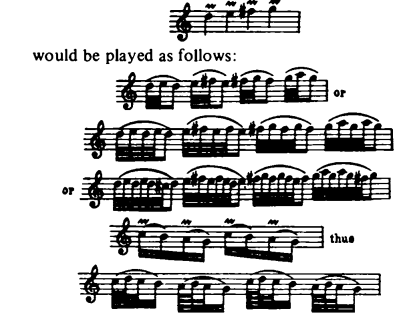

In all his examples provided across his three methods, Vanderhagen indicates that the grace note should be executed as half the value of the main note. However, there was a greater variety of uses for grace notes. A grace note could be executed very rapidly, without affecting the written rhythm for example. In his violin method, Leopold Mozart discussed the different approaches to this type of ornament in detail, differentiating between “Long Appoggiatura” and “Short Appoggiatura” and offering a great variety of options and possibilities for utilizing it.6 Other writers for the clarinet, like Lefèvre, also suggest a wider variety of options to employ the grace note, offering possibilities like “double grace note”, “prepared grace note”, and even mentioning portamento under the same category (example 8.10).7

Other Ornaments and Cadenzas

Though consistent with the embellishments he wished to highlight in his books, Vanderhagen chose to omit two of the ornaments he had discussed in his 1785 treatise. The first one is the Accent; a note placed one or two steps above the one the player wishes to emphasize, that is heard just before. This enriches the melodic line, and, in the author's words, “distinguished and reunites the expression of the note that precedes it with the note which follows” (example 8.11).8

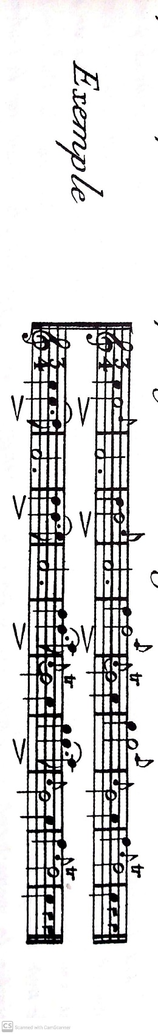

In addition, in this earliest method, Vangerhagen also wrote of the martellement (or mordent), an ornament that was omitted from later editions. When discussing the mordent, Vanderhagen stressed the difference between that and a trill, by suggesting that, while a trill borrows the note above the main note, the mordent borrows the one below it. Furthermore, unlike the trill, the mordent starts from the main note, and not from the borrowed one (example 8.12).

This definition is consistent with that of Leopold Mozart. Nevertheless, other writers held different approaches to the mordent; Lefèvre merely stated that it is “nothing more than a short trill”9, while Ozi provided the following example (8.13) for executing the ornament.10

More than half a century later, Carl Baermann validated Lefèvre’s approach in his own method, providing the given examples (8.14).11

This change can possibly suggest a change in taste and aesthetic between that of the mid-eighteenth century, to that of the wake of the nineteenth century and later.

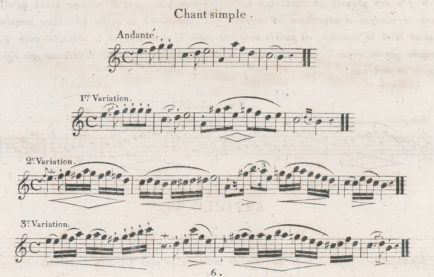

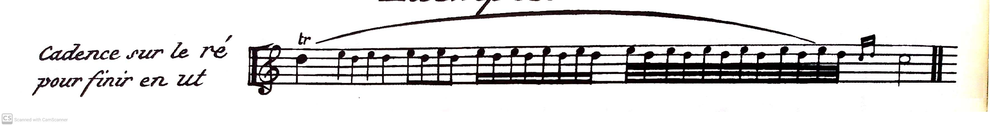

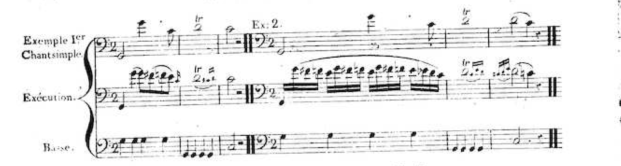

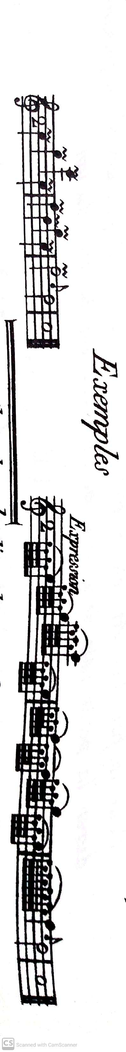

Unfortunately, Vanderhagen did not discuss the topic of melodic variations and alterations, cadenzas, or improvisation as means of embellishment and self-expression. This practice was incredibly significant to solo performers throughout the eighteenth century, and well into the nineteenth century on occasions. Contemporaries like Lefèvre and Ozi, on the other hand, offered examples of this performance practice (examples 8.15-8.18).