Chapter X: Clarinets of Different Sizes and Pitches

During the first half of the eighteenth century, the preferable transpositions for clarinets were C and D. The baroque clarinet was mostly played on the overblown high register and was known for its bright trumpet-like sound - the name “clarinet” actually derived from the word “clarino” (little trumpet). Idiomatically, the clarinet was used in the same manner as brass instruments such as trumpets and horns, playing fanfare-like arpeggios; hence the choice of transposition.1

With the rise in its popularity and widespread in the 1750s, more composers were compelled to experiment with this still new and fresh instrument. Inspired by the growing range, attributed to the many developments in the instrument's design, they started employing the lower notes of the clarinet, which created a different color and tone. The court of Charles III Philip in Mannheim produced many examples where the use of winds was experimental and relatively flexible; which were also critically important to the development of the clarinet.2 With composers like Johann Stamitz and his sons Carl and Anton Stamitz, Franz Xaver Richter, Peter von Winter, and Franz Pokorny, this court was the first to add a pair of specializing clarinetists to the orchestra in 1759.3 The Mannheim school composers also enriched the then-small repertoire of the instrument through a number of virtuosic concertos for the B♭ clarinet.4 They innovated the writing for clarinets by incorporating more extensive use of the chalumeau register, leaps of more than two octaves, use of dramatic dynamic contrasts, and adaption of a lyric style in slow movements; these innovations revealed a new seductive side of the clarinet.5 The new approach to writing for the clarinet soon became popular all over Europe, particularly in Paris – one of the most important cultural centers at the time. This establishes a strong connection between the Parisian scene and the Mannheim court, as it was during Johann Stamitz’s tour to Paris in 1754 that he first got to include a pair of clarinets in a symphony, and experiment writing for the instrument.

It was around this time that a changing approach to clarinet transpositions started to reveal a growing fondness for the warm tone of the B♭ and A clarinet, as opposed to the piercing trumpet-like tone of the C and D clarinets.6 In Valentin Roser’s essay Essai d’instruction à l’usage de ceux qui composent pour la clarinette et le cor, he lists seven transposing clarinets in G, A, B♭, C, D, E, and F. He names the A, B♭, C, D as the most commonly in use, and the G clarinet as the rarest of the bunch. The G clarinet possessed a very soft and mellow tone and was seen only on rare occasions when it is absolutely impossible to use any of the others. In addition, he mentions that the high-pitched clarinets in E and F are only used in large orchestras that play “very loud”.7 From his description, it is apparent that the different transpositions of the clarinet mean more than a matter of convenience to the player and ability to play in different keys. Each clarinet had its own timbre and characteristics, thanks to which it was employed.

Another interesting essay was published in 1772 in Paris by Louis-Joseph Francœur, titled Diapason general de tous les instruments a vent. In this essay the writer specified eight transpositions: G, A B♭. B, C, D, E, and F, on each he elaborated and specified its sound characteristics and recommended tonalities:8

-

Large clarinet in G – the softest clarinet, not strong in an orchestra, sad and lugubrious.

-

Clarinet in A - much less somber than the G, but still soft in quality.

-

Clarinets in B and B♭ - are stronger, and project more than the A clarinet.

-

Clarinet in C - more sonorous than the B♭ or B clarinet.

-

Clarinet in D - very sonorous and very striking, called the brillante clarinette.

-

Clarinet in E - not strong because of its small size.

Of this list, Francœur highlights the A, B (and B♭, with corps de rechange), C, and D as essential for every clarinetist to own.

In his earliest method, Vanderhagen named five sizes of clarinets in D, C, B, B♭, and A. He characterized the D clarinet’s tone as shrill, and claimed it would be rarely used, and only in “those pieces that make noise”. Vanderhagen went on to highlight the A clarinet as the mellowest in the list, and the most fitting for soft and gentle pieces.9

Thus, it is noticeable that in the passing years between Roser’s and Francœur’s essays, the extremes of the clarinet family – highest and lowest – became less common. In this installment, Vanderhagen failed to mention the smallest and highest clarinets in E and F, and the lowest G clarinet. Note that he described the tone and use of the previously popular D clarinet in the same terms as Roser had described the even higher E and F clarinets two decades before.

Curiously, in Vanderhagen’s 1799 book, he extended the variety, and concisely discussed the clarinets he previously omitted; he mentioned the G (alto) clarinet, or Clarinet d’Amore, which he claimed would never be used in orchestral music, and the high E♭ and F clarinet, which would be employed exclusively in military music. Of the smaller clarinets in E♭ and D, he merely writes it would be used “in the same manner as the horn”.

In his 1802 method, Lefèvre also discussed the necessity of different clarinet sized and suggested when each should be employed. Like Vanderhagen, he also focused on the C, B, B♭, and A clarinets, but completely overlooked any other size mentioned above.10

It is, thus, established that through the second half of the eighteenth century, it was necessary that a clarinetist owned at least four sizes of clarinets (In C with corps de rechange of B, and B♭ with corps de rechange of A, and occasionally D clarinet). Moreover, it seems that the writing style for the instrument, its technical and idiomatic evolution, as well as the changing fashions and tastes in music, had an effect on the popularity and preference of the mentioned above sizes.

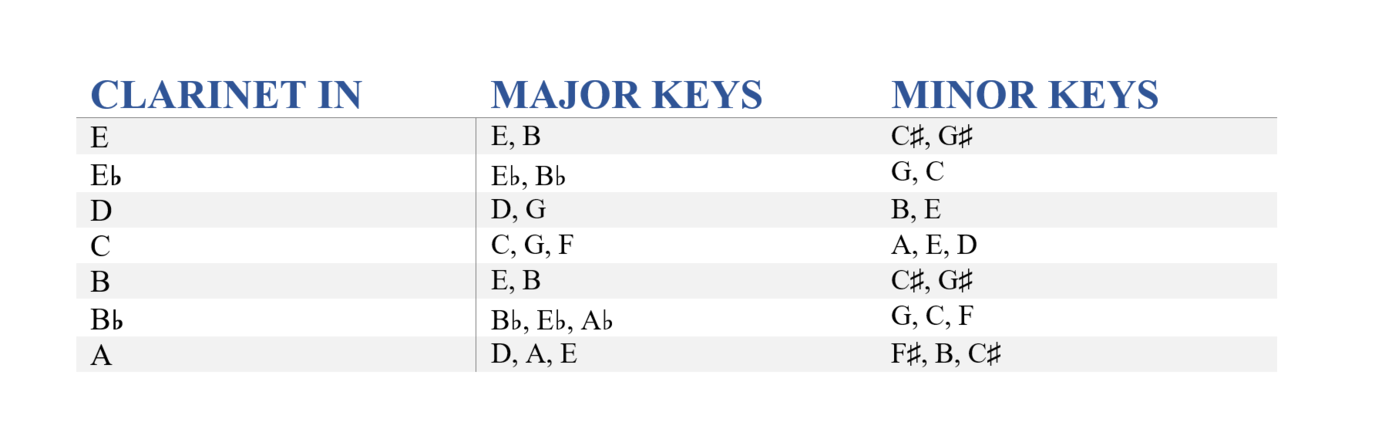

The following table demonstrates the necessity of different sizes of clarinets for different tonalities, particularly when playing in mixed ensembles, according to the sources mentioned above:

With the explorations of players and instrument makers of creating a clarinet more capable of playing in distant keys, switching instruments in order to compensate for the changing tonalities became less common. Composers writing for the clarinet could now venture fearlessly into different tonalities while writing for the instrument, as reflected in many compositions written for the twelve-key clarinet.

This brought a certain tear in the clarinet society in the second decade of the nineteenth century, particularly in Paris. New, experimental voices in instrument-making saw the potential in the twelve-key clarinet and aimed to make further improvements to the point of eliminating the need for more than one clarinet. Iwan Müller created his Clarinette Omnitonique - presented in Paris in 1812 - with the intention of creating an instrument able to be played in all keys. In the process of creating this instrument, and among the many innovations it featured, Müller combines the right-hand joint and the stock into one piece and thus he terminated the previously vital corps de rechange. This was one of the main reasons the faculty of the Paris Conservatory rejected the instrument, primarily on the basis that the inventor aimed to eliminate the use of all clarinet transpositions and remain only with the B♭ clarinet, which he considered superior in tone and stability.11 Nonetheless, the traditionalists of the prestigious institution could not keep Müller’s brilliant invention from becoming incredibly popular and successful, as it sure had its merits, and eventually became the instrument of choice for clarinetists in Paris.

As established before, Vanderhagen was one of the old-school traditionalists. Having played on the five-key clarinet for most of his career, he probably did not venture far from the classical clarinet; as also evident from his focus on the twelve-key clarinet in his last method. However, he seems to have been self-aware, or even self-conscious, about that. In his latest method, where targeting the twelve-key clarinet seems barely relevant in Paris of 1819, he completely avoided the topic of different-sized clarinets; which he had extensively discussed in his previous publication.