PIECES, CHORDS AND PRECARITY

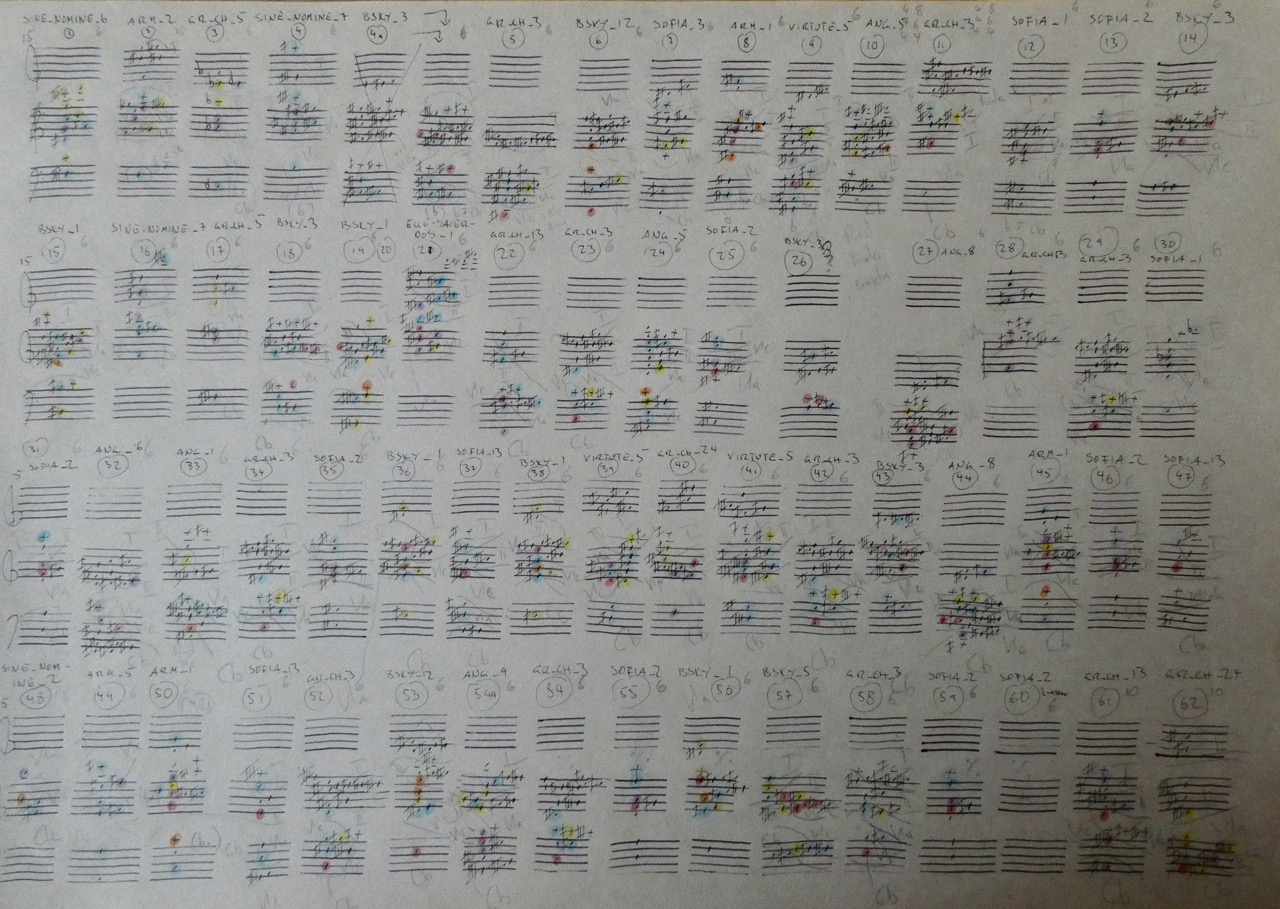

In the following part I will present my work with chords from the BOOK OF CHORDS around the pieces that are part of my artistic results for my Ph. D. project PLAN TO UNPLAN.

Those are pieces that I have written in the past 5 years. Thereof six orchestra pieces and one chamber musical piece:

FLÜGEL for orchestra (2020) - commissioned by Claussen Simon Stiftung and the Elbphilharmonie Visions Festival Hamburg

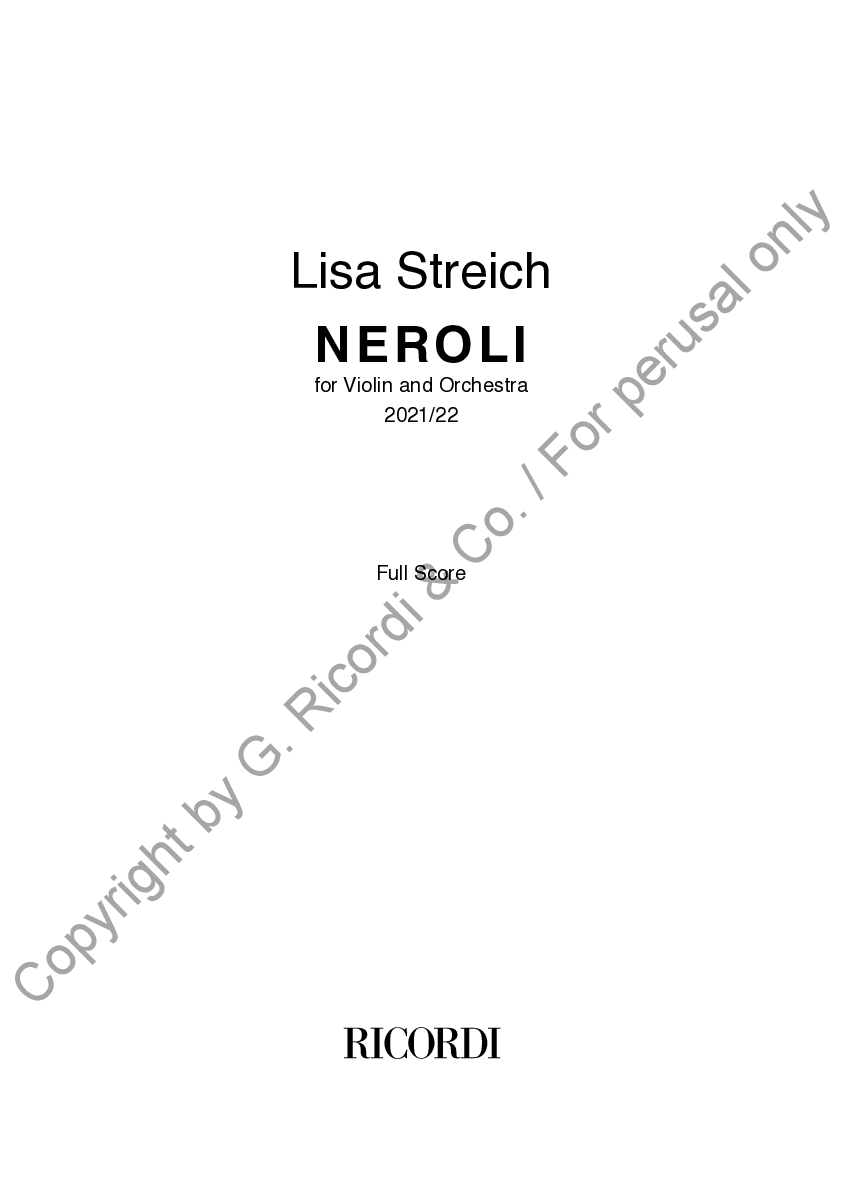

NEROLI for violin and orchestra (2021) - commissioned by Münchener Kammerorchester, Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Orchestre de Picardie

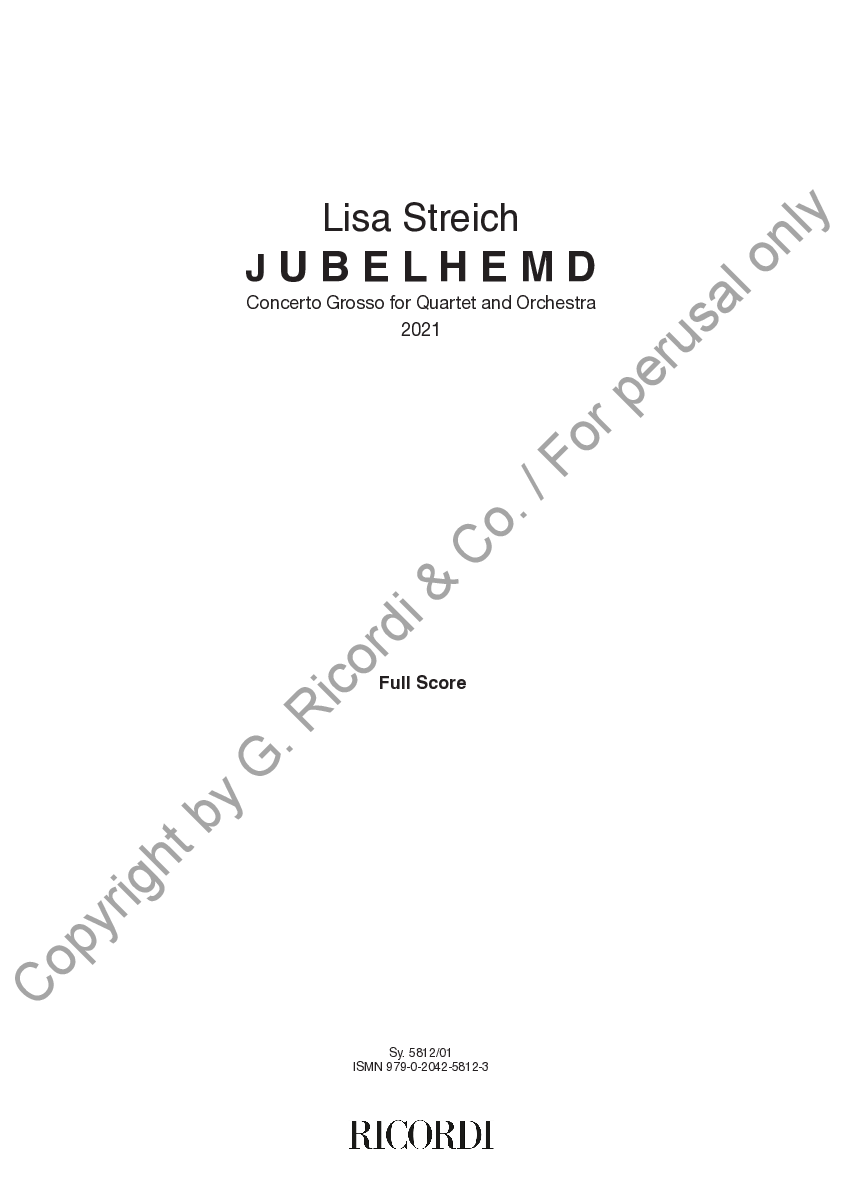

JUBELHEMD for quartet and orchestra (2021) - commissioned by Swedish Radio Orchestra, Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, Malmö Symphony Orchestra and Norrköping Symphony Orchestra

BALLHAUS for orchestra and props (2022) - commissioned by Staatstheater Hannover

ISHJÄRTA for orchestra (2023) - commissioned by Berliner Philharmoniker

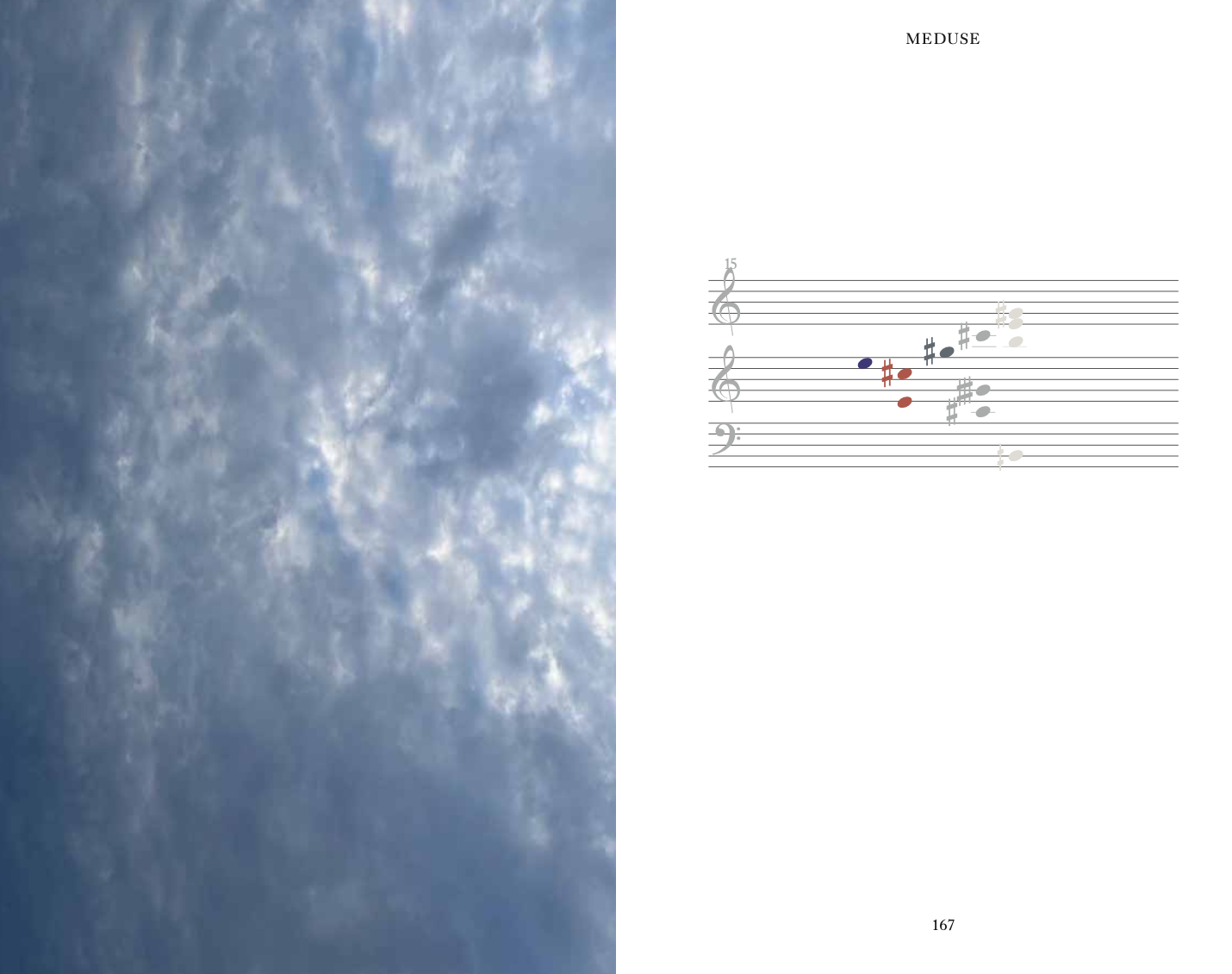

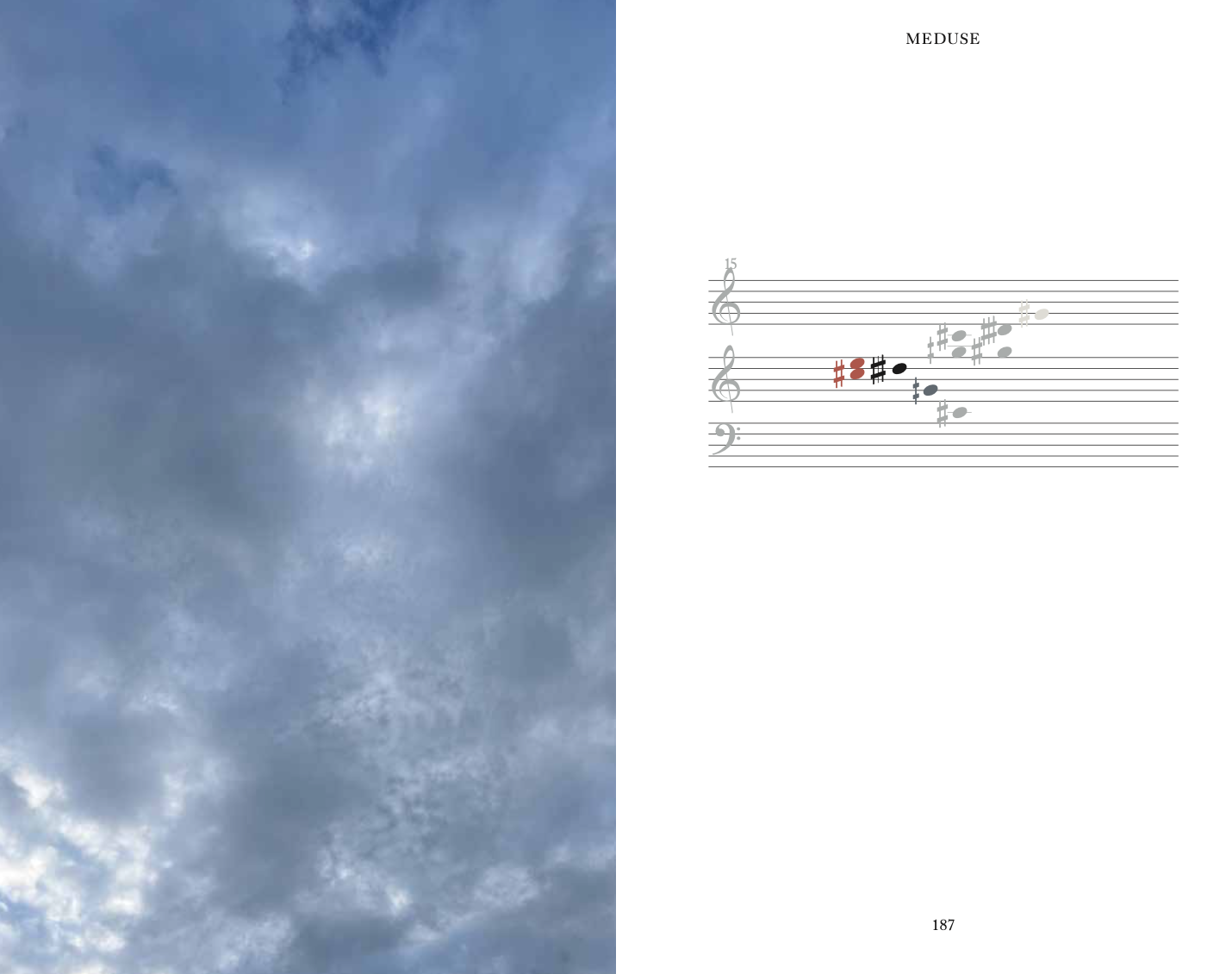

MEDUSE for trumpet and orchestra (2024) - commissioned by Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Lucerne Festival, WDR Symphony Orchestra and Barcelona Symphony Orchestra

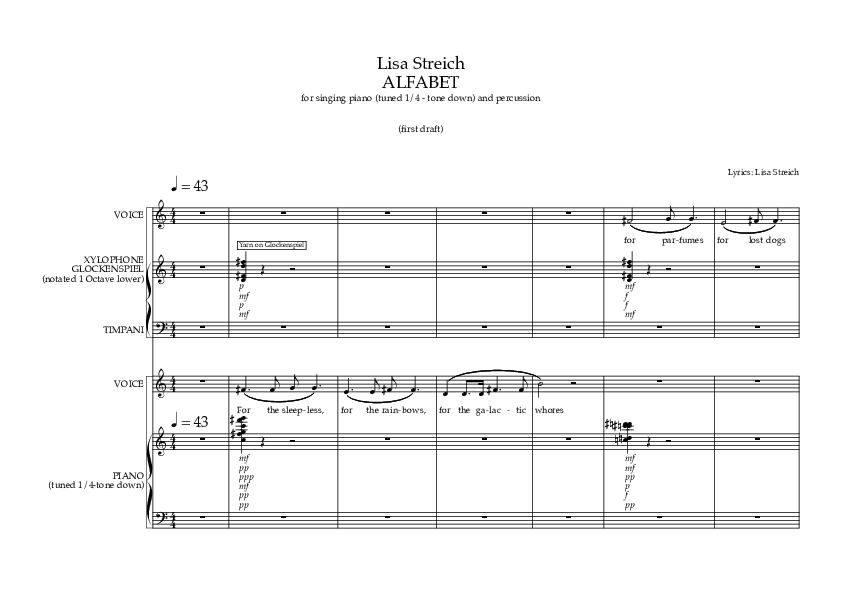

ALFABET for quarter tone down tuned piano and percussion (2024) - written for Jennifer Torrence and Ellen Ugelvik

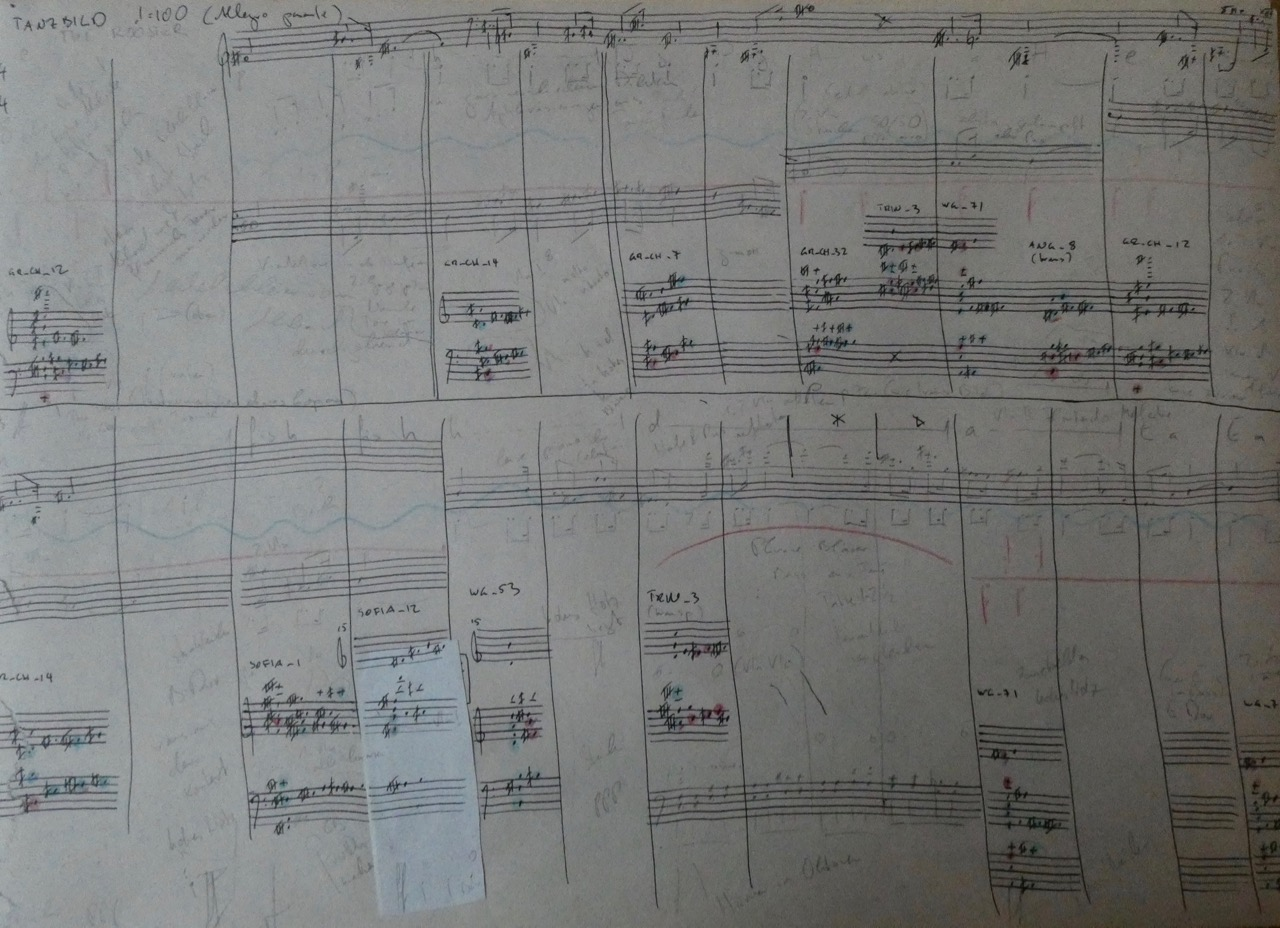

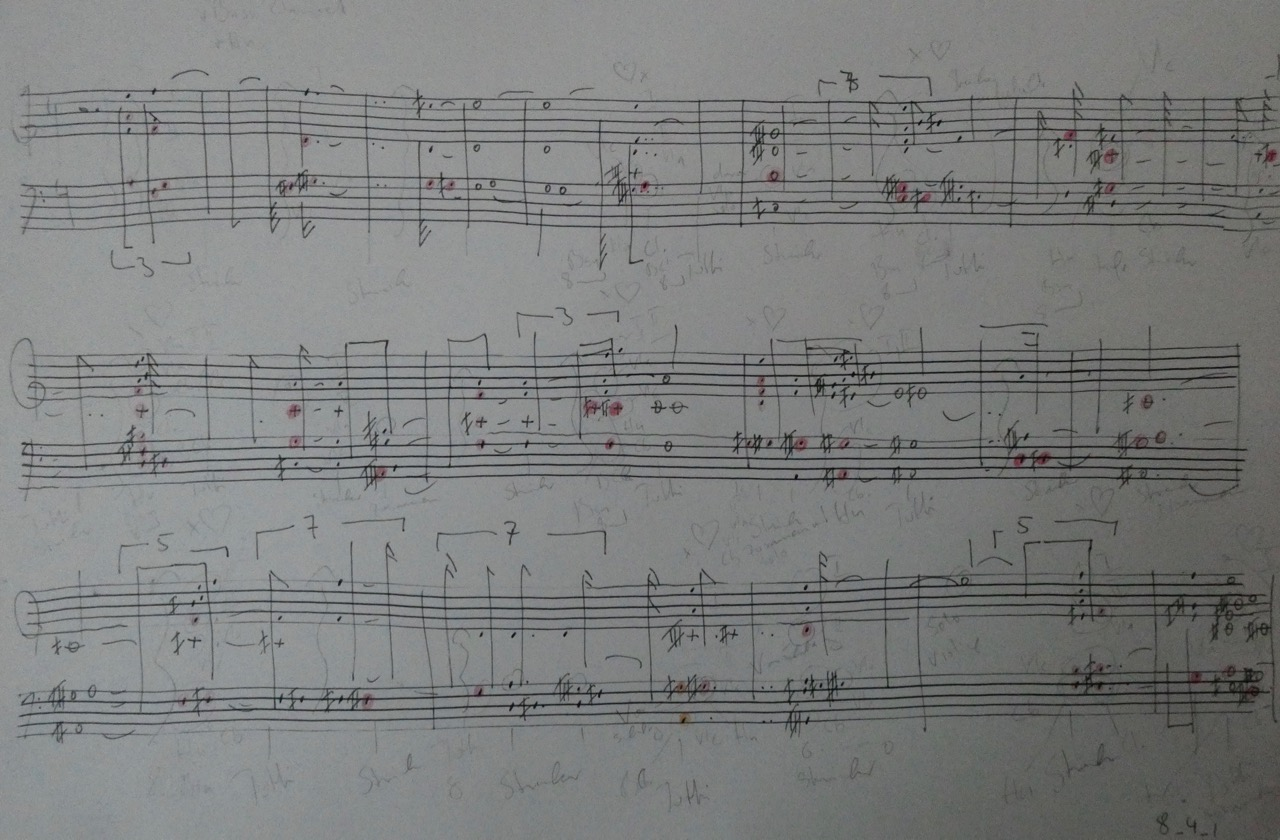

In this presentation, I aim to illustrate the use of chords from my book BOOK OF CHORDS through text, audio examples, and scores. I will systematically go through the pieces and address the peculiarities of the various chords and how they are orchestrated to come as close as possible to the expression of the chord or even to amplify the expression. Furthermore, I will address the precarious moments, which may vary from piece to piece. One must consider with orchestral commissions that a small deviation from the norm can have significant implications. Typically, there is between three to five hours of rehearsal time for a 20-minute piece. This means I must be as efficient as possible in notation to bring something new into the orchestral world in the shortest possible time. Also, the risk of trying something new means that there is less time for the whole piece of music in the end so it has to be chosen consciously how far from the norm I dare to go in one piece. My experience is that I can lean a bit more out of the window from piece to piece, but taking a big step all at once is difficult since there is usually no opportunity for experimentation beforehand. And everything I am not sure of concerning the outcome takes valuable rehearsal time. Everything that needs to be newly tried takes away valuable rehearsal time for the other things to rehearse in the piece and ultimately diminishes time for the musical result of the entire piece. My experience tells me that one must take small steps to perhaps reach the ultimate goal after several orchestral pieces. However, there is also a certain beauty inherent to that fact; I adapt to the character and pace of the orchestral apparatus, and it also gives me time retroactively to explore things slowly.

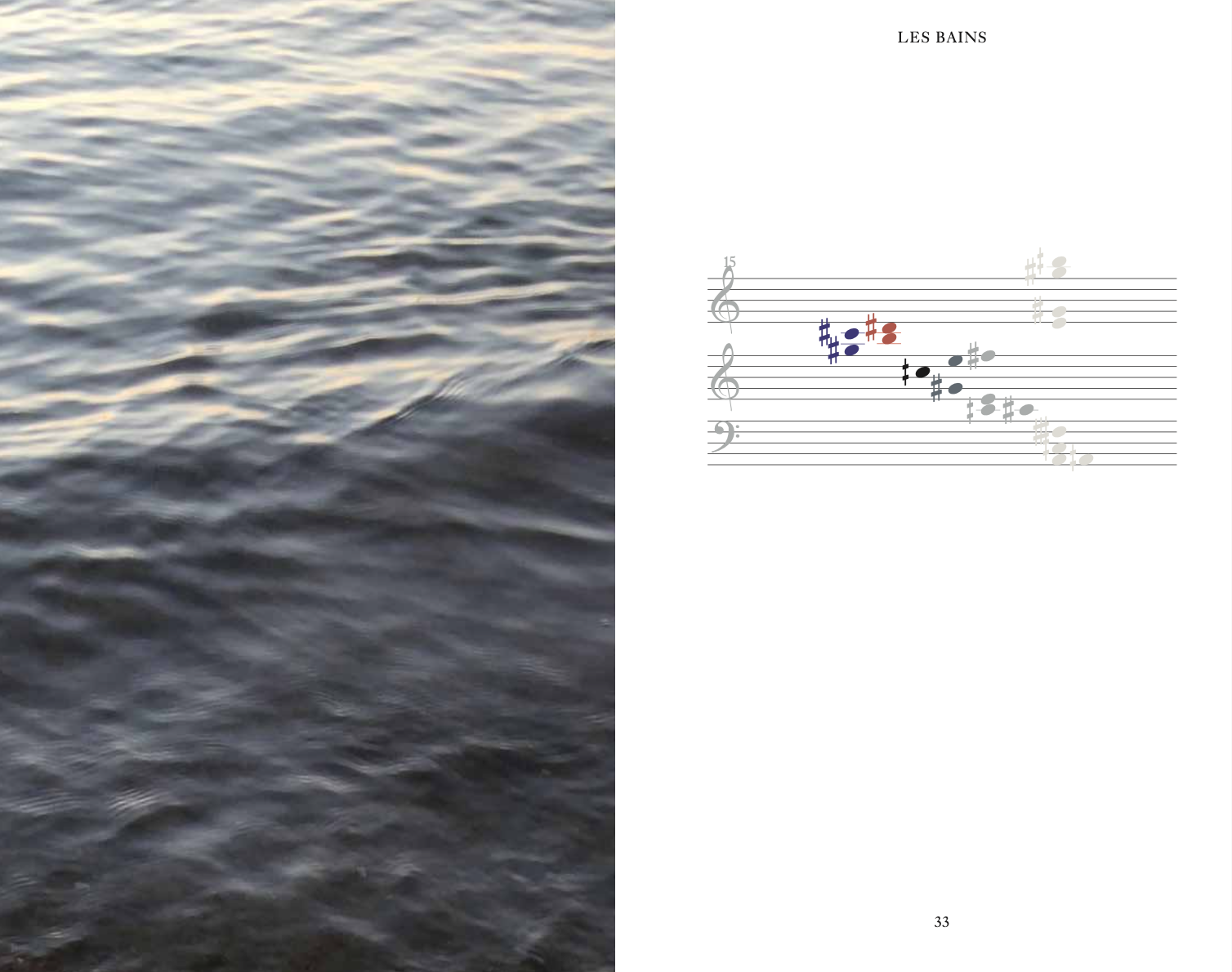

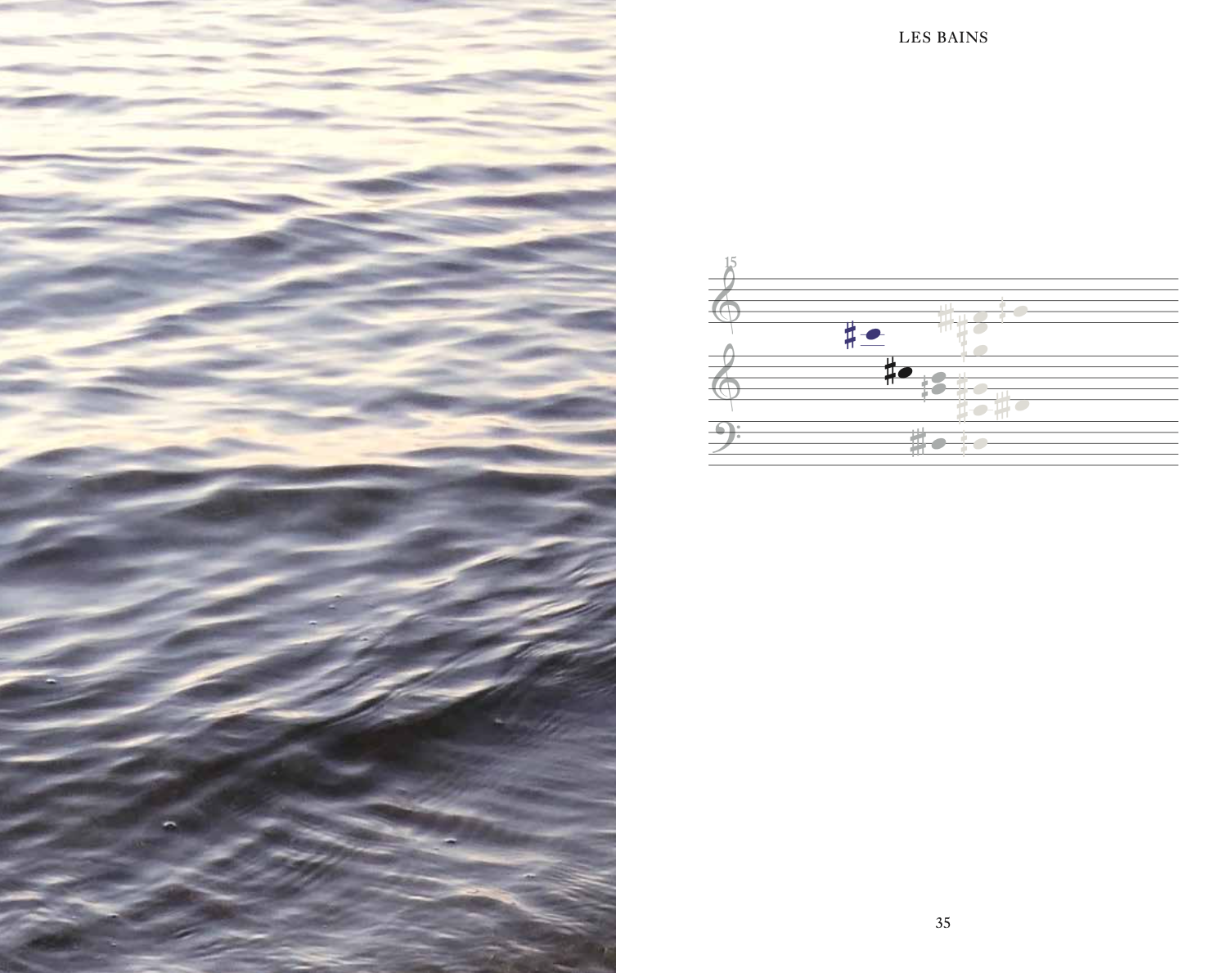

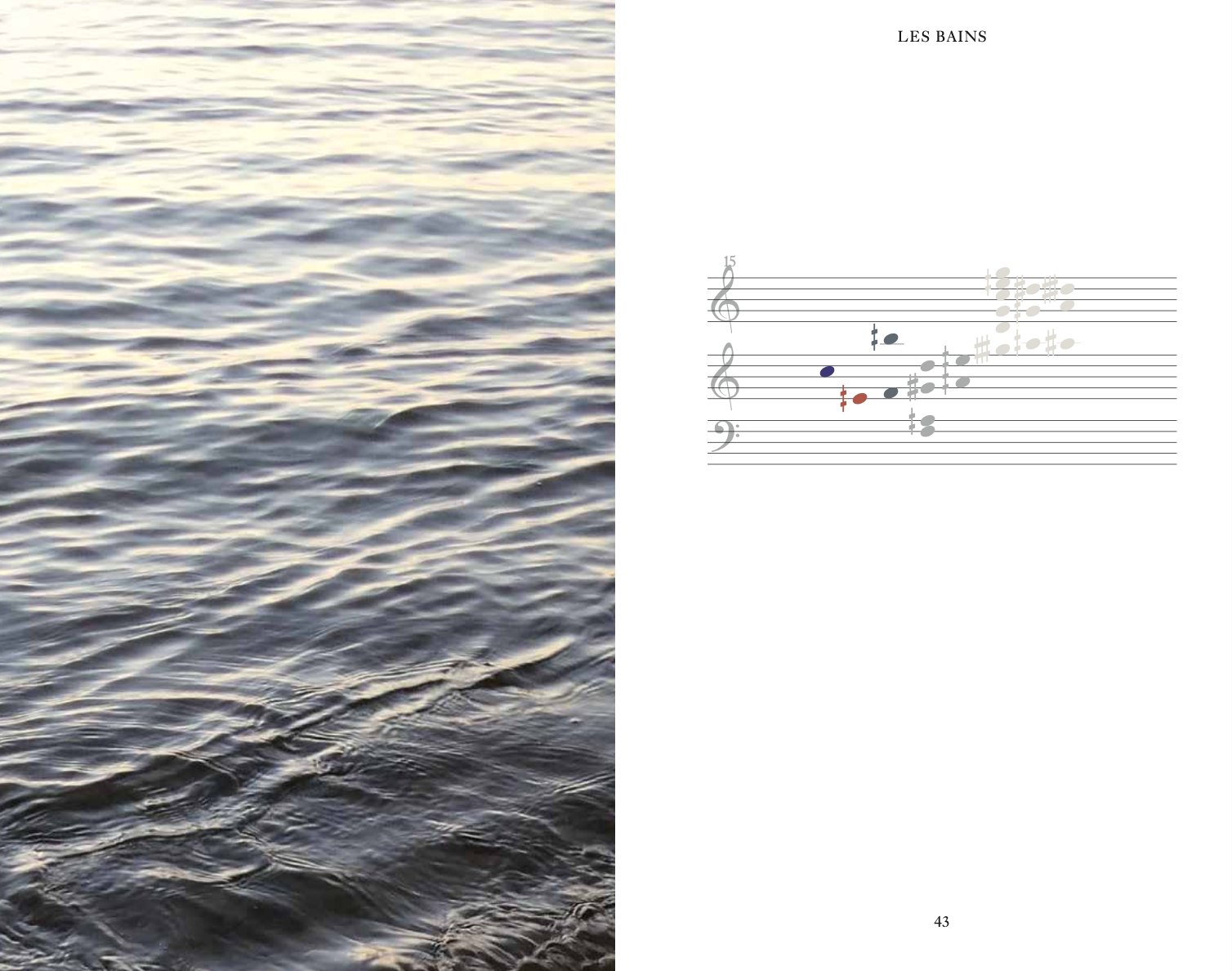

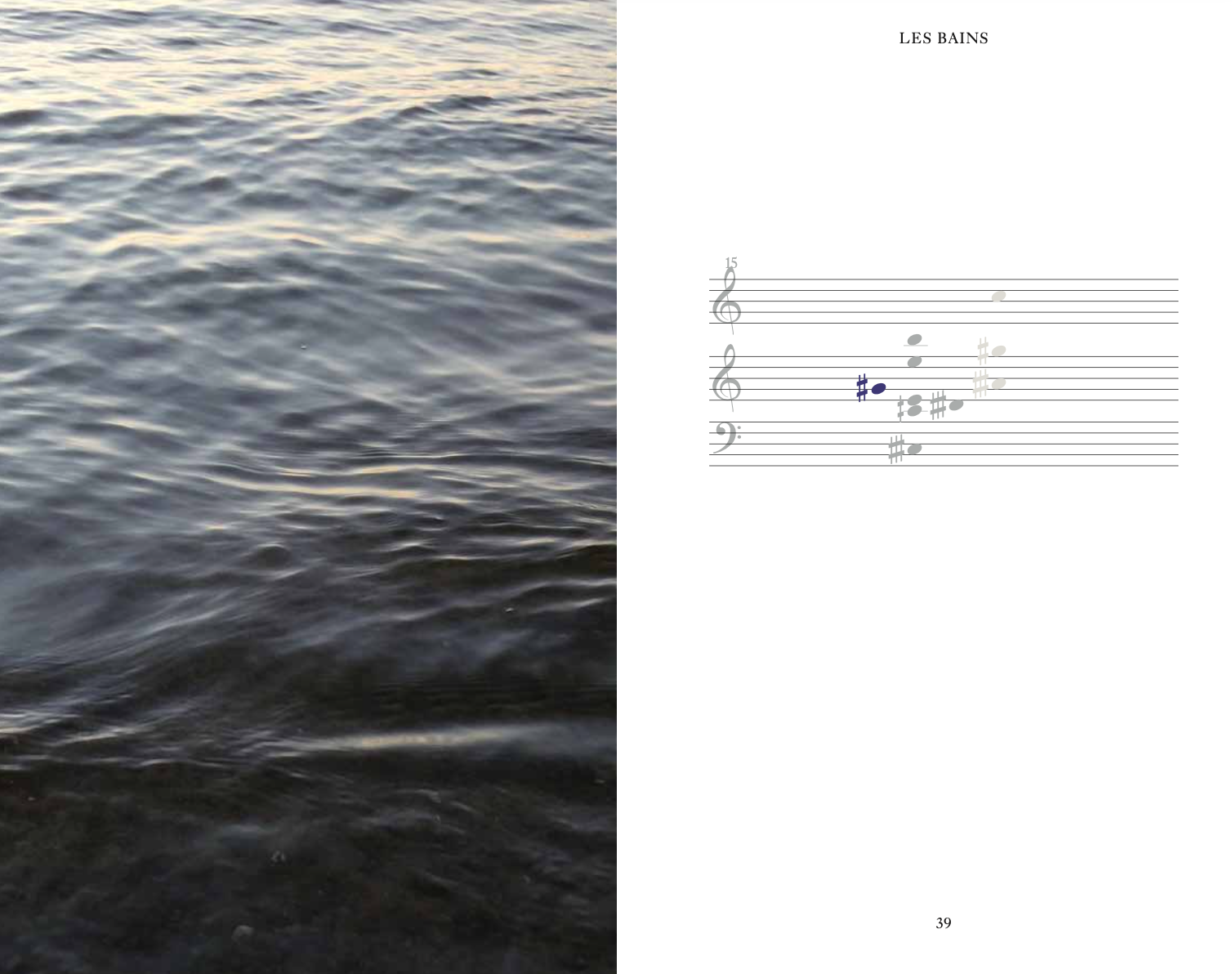

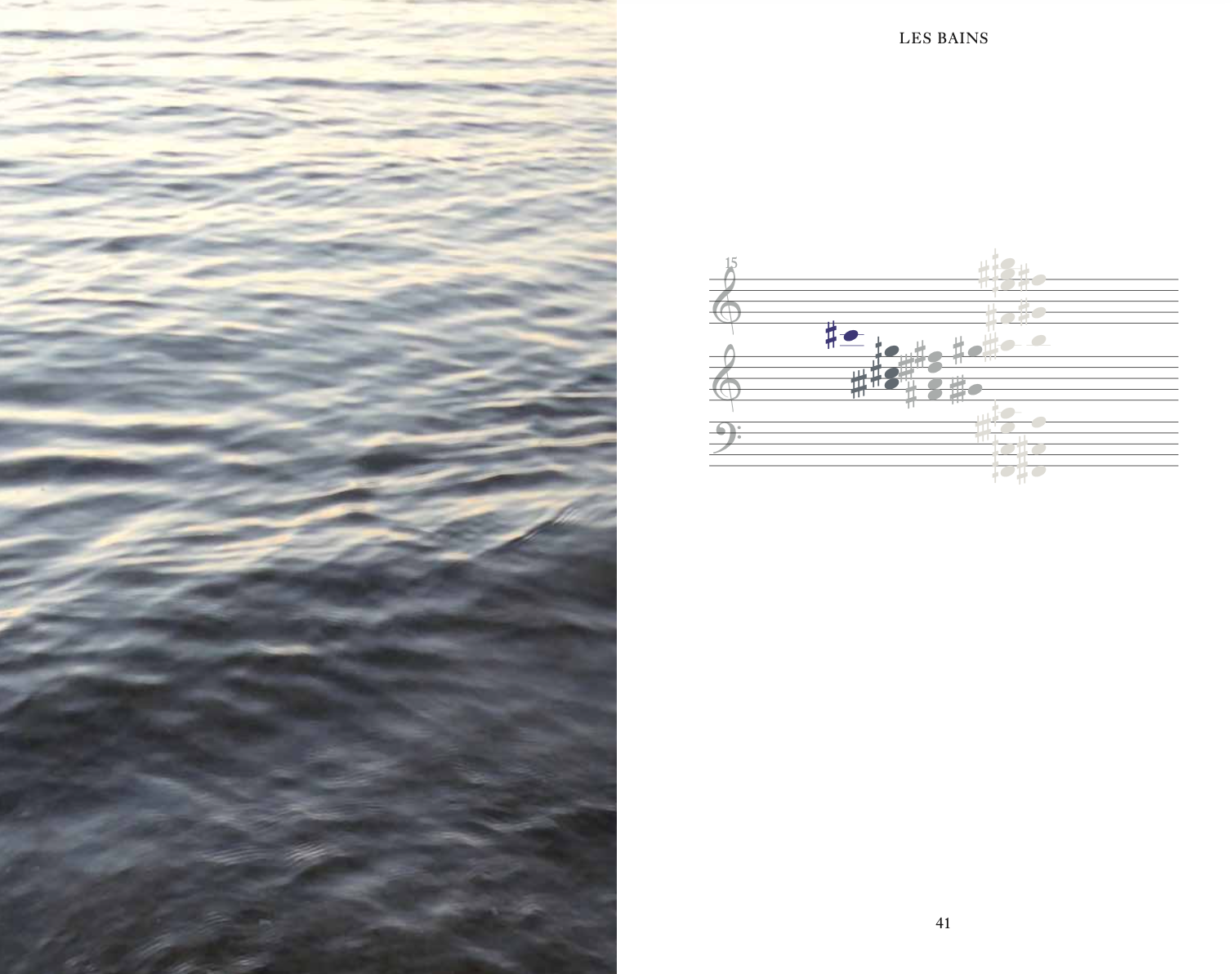

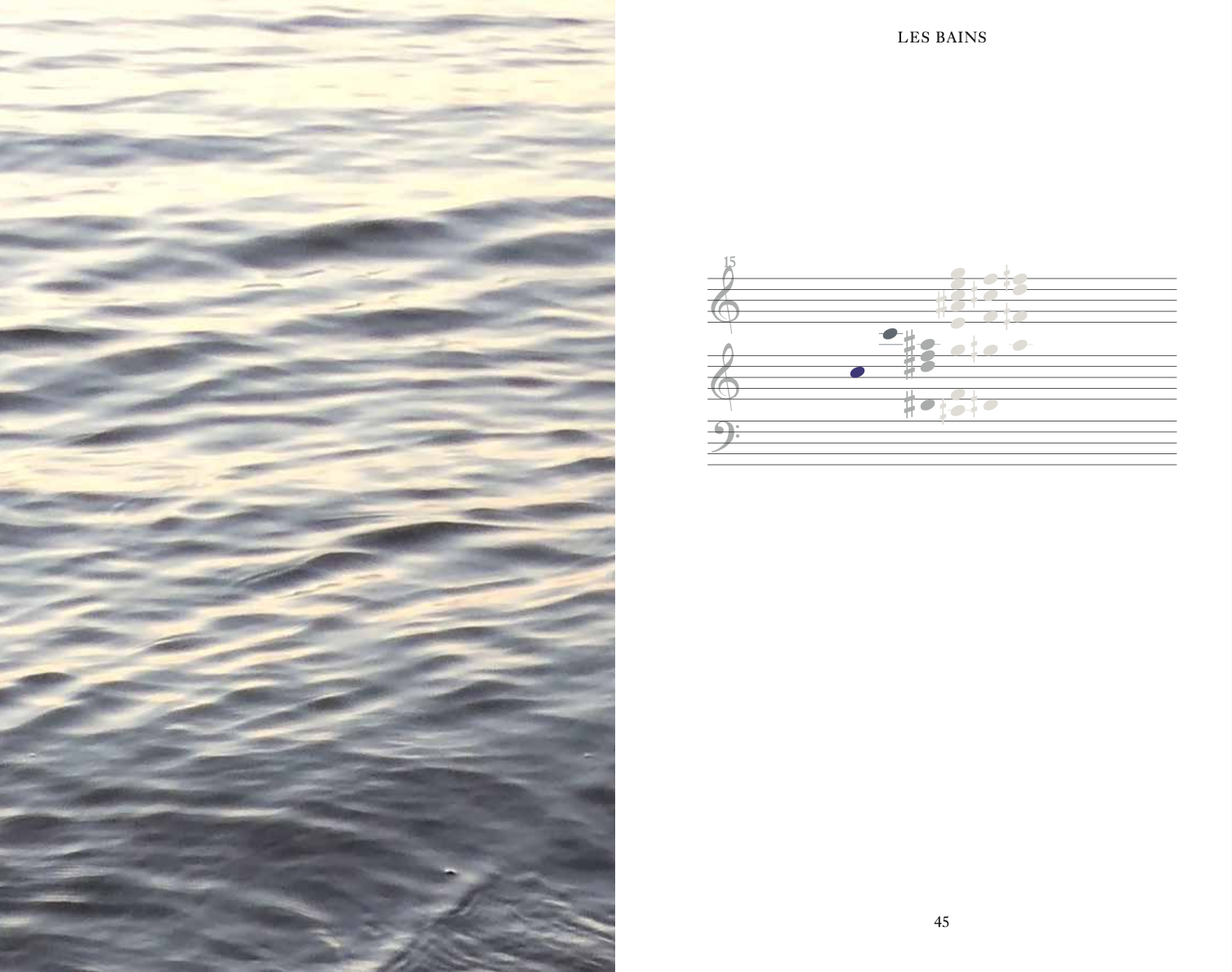

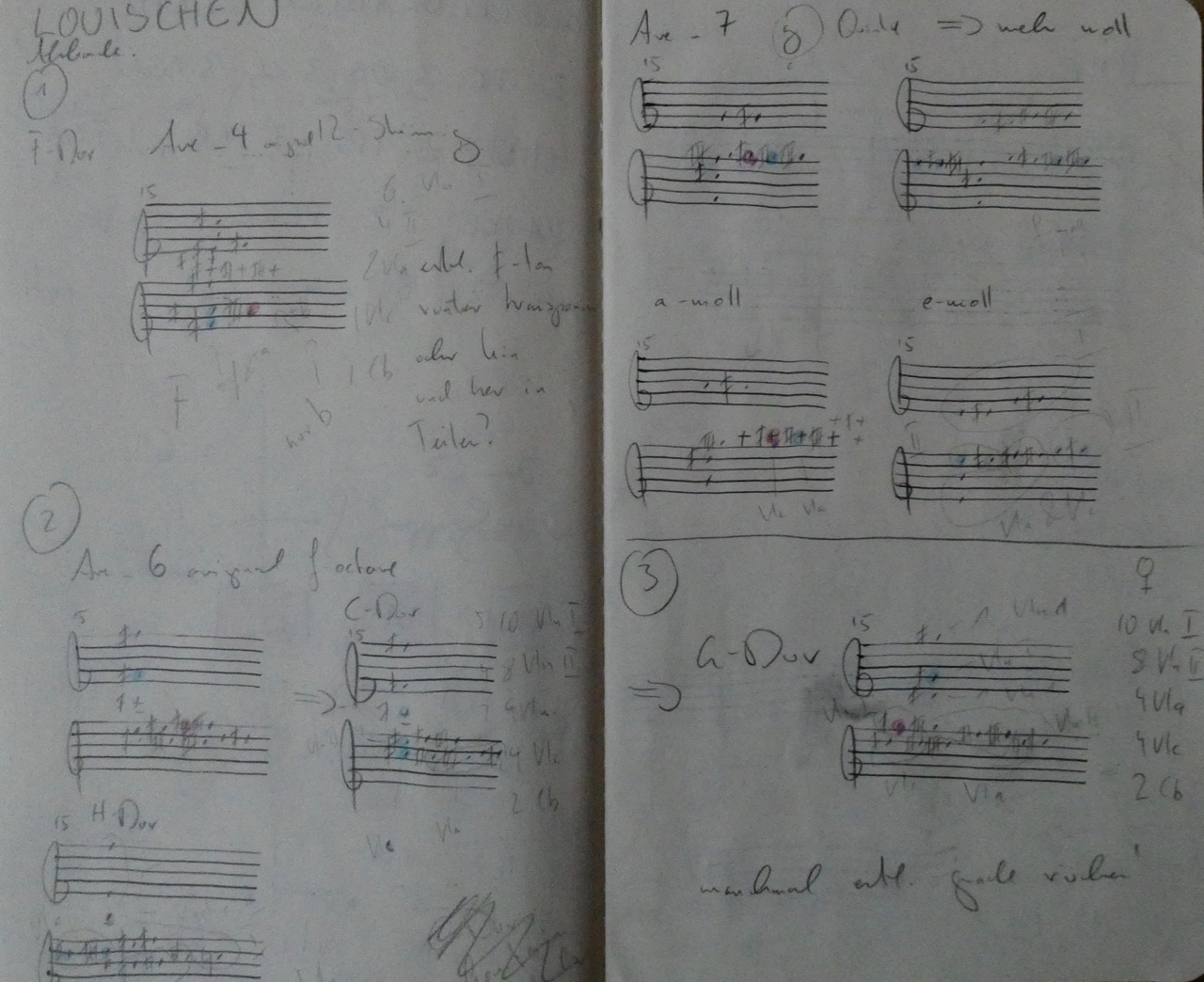

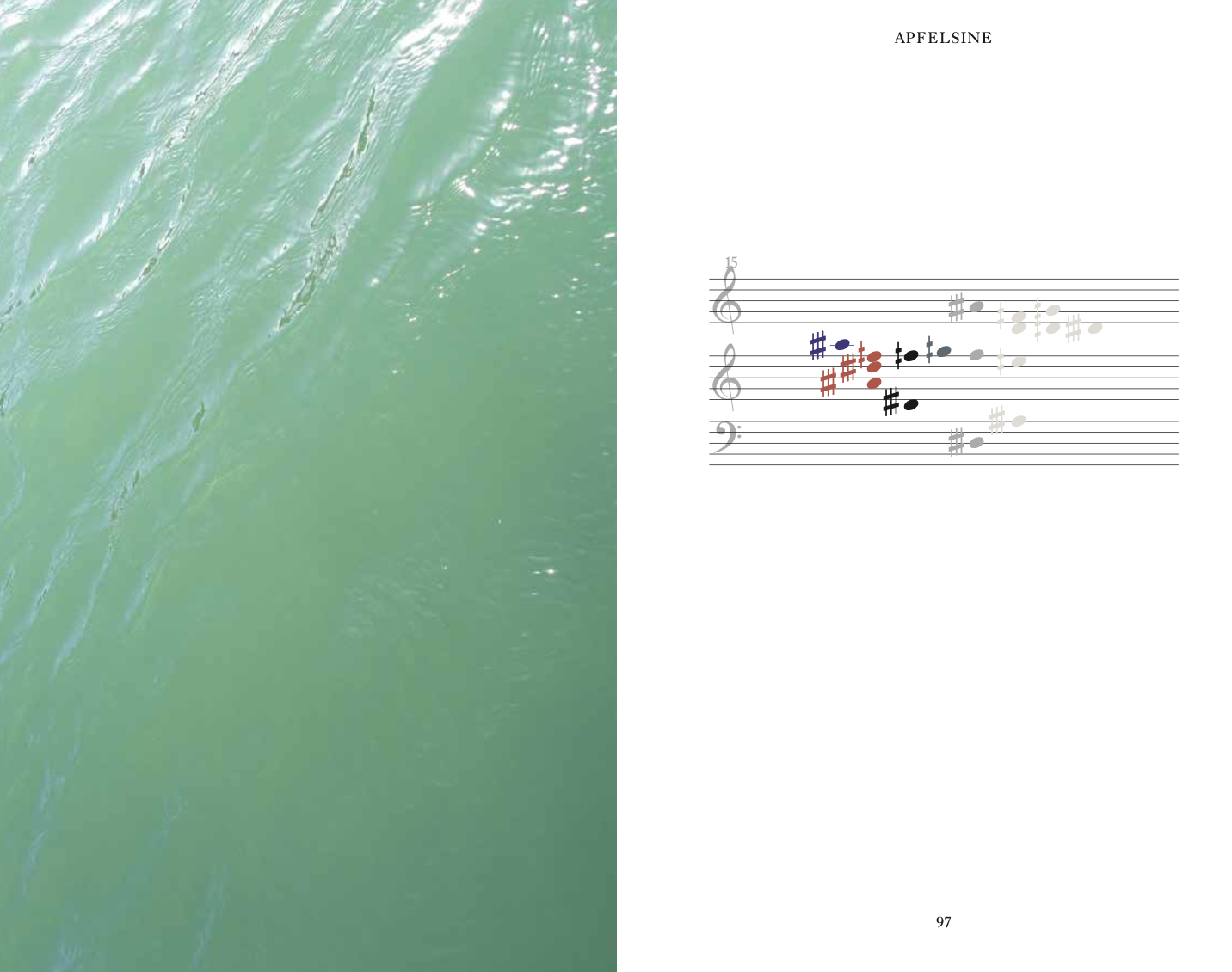

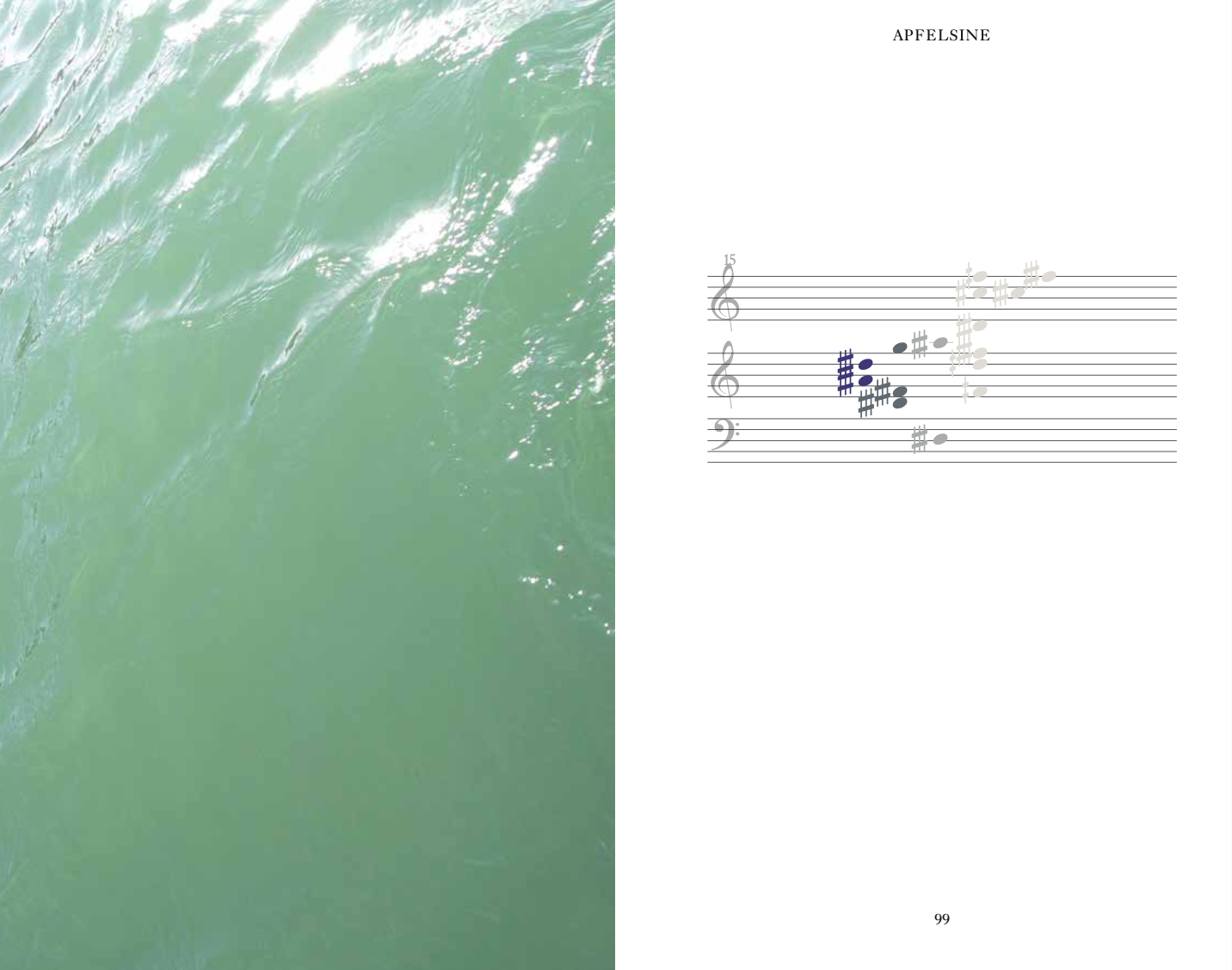

The chords from the book BOOK OF CHORDS play a central role in these pieces. Some of them are old chords that I found 2017 for example, like GLORIA and GEBET, and I reuse them. Some are chords that I recently searched for specifically for a piece. For instance, I searched for the chords from the chapter LES BAINS for the piece NEROLI (2021). A chord group with a warm, physical and enveloping expression which qualities I try to capture in the referring poem and photographs to the chord group. If I were to search for this expression again in the future, I can refer back to these chords. If I'm looking for an expression that isn't yet in my catalogue, I will search again. So, it's the expression that I have in mind that comes first, then the search for the right chords and after, I can write the piece.

FLÜGEL (WINGS) is a choreography of different kinds of wings that are being projected onto the orchestra. Right, left, tutti, from the left to the right, from the right to the left. The most different kinds of wings spread above and through the orchestra. They go from tender nets of wings that spread through the orchestra through soloist counterpoints to crashing tutti wings.

The entire piece, viewed harmonically, revolves around a continuous pulling and releasing. My aim was to find chords that amplify each other in their pulling, releasing, or hovering characteristics. In the faster passages, in the so-called tutti wings, they alternate. And then there are moments where they remain standing in their characteristics. In the end was the biggest question: can these qualities coexist simultaneously within one and the same chord?

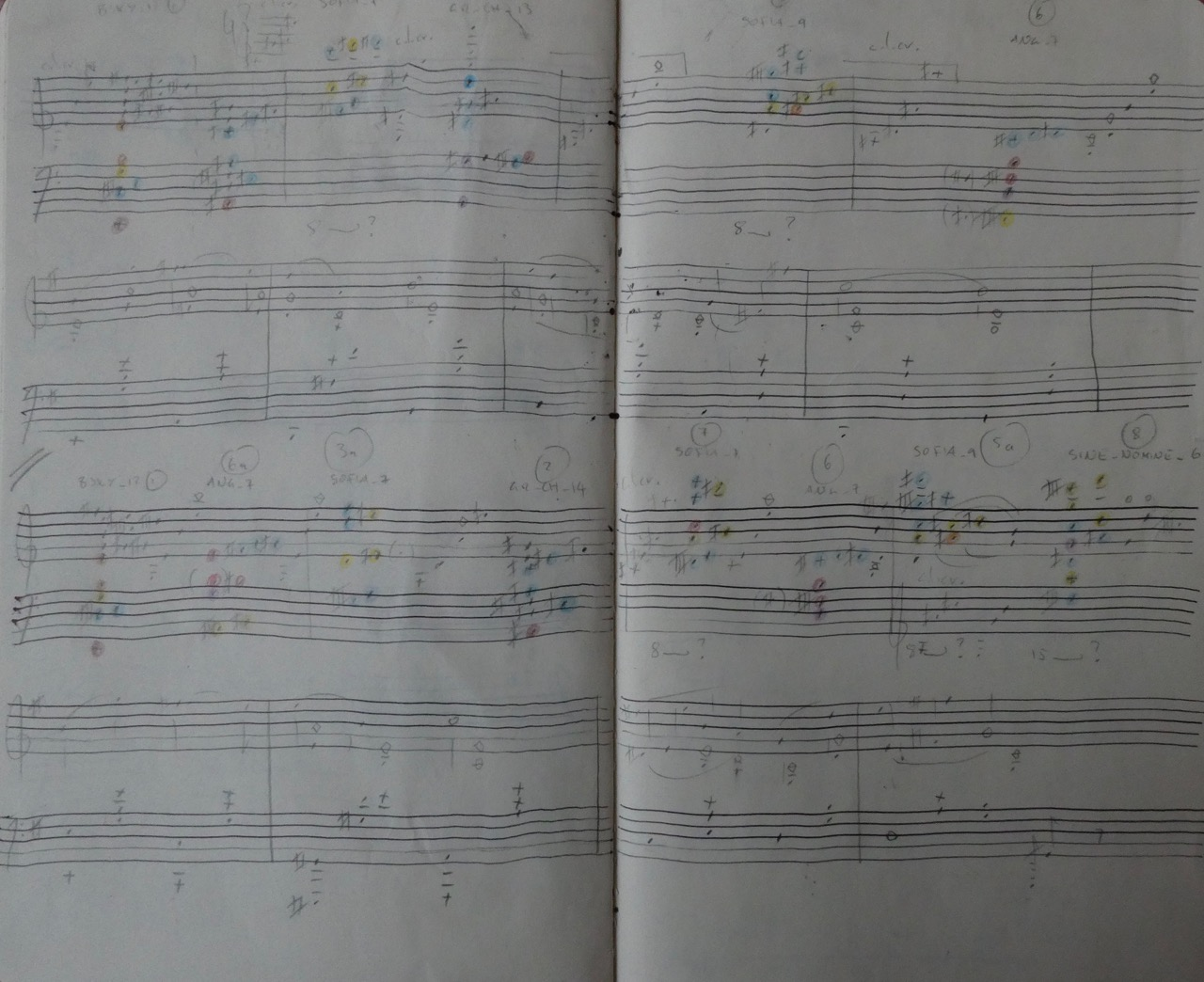

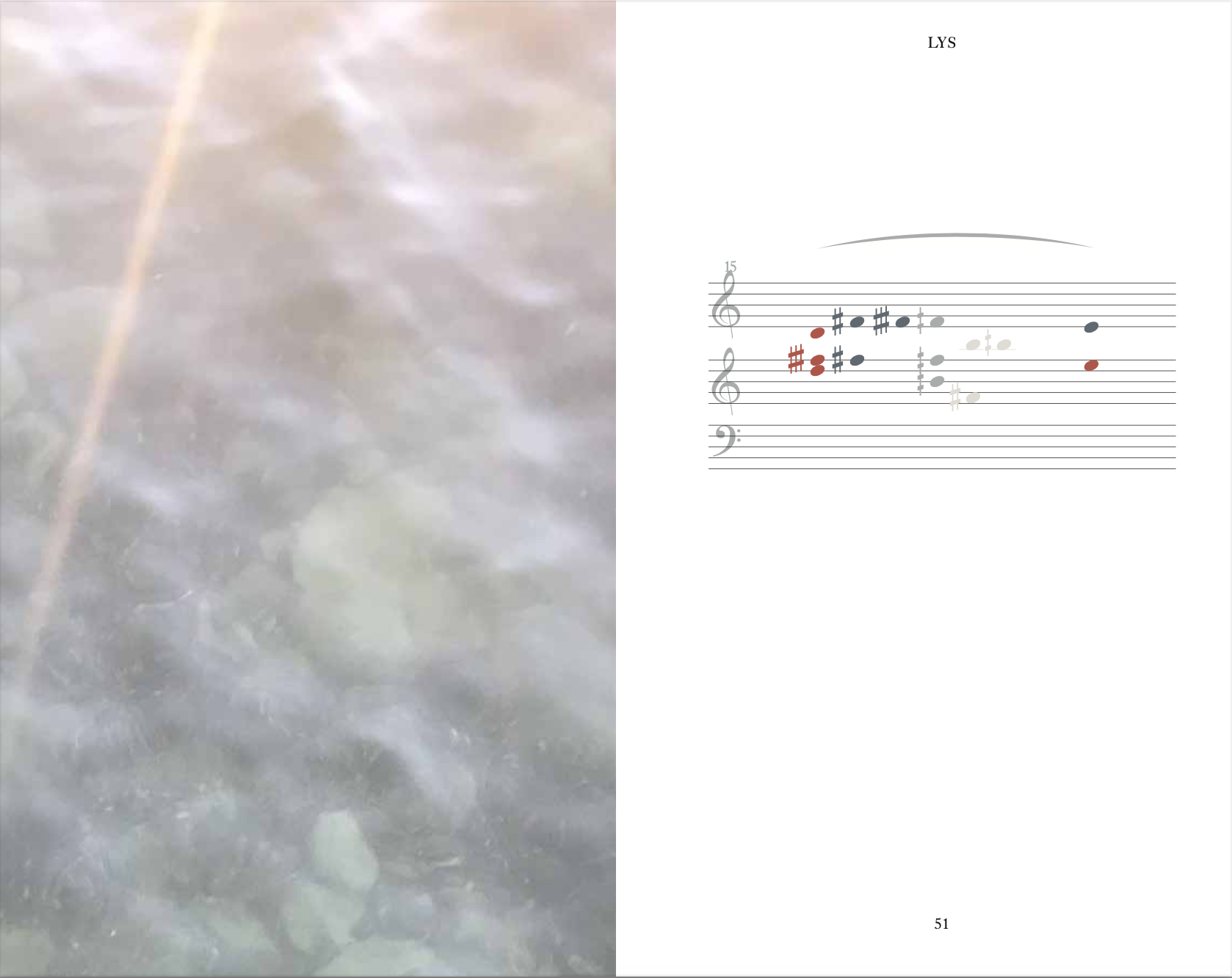

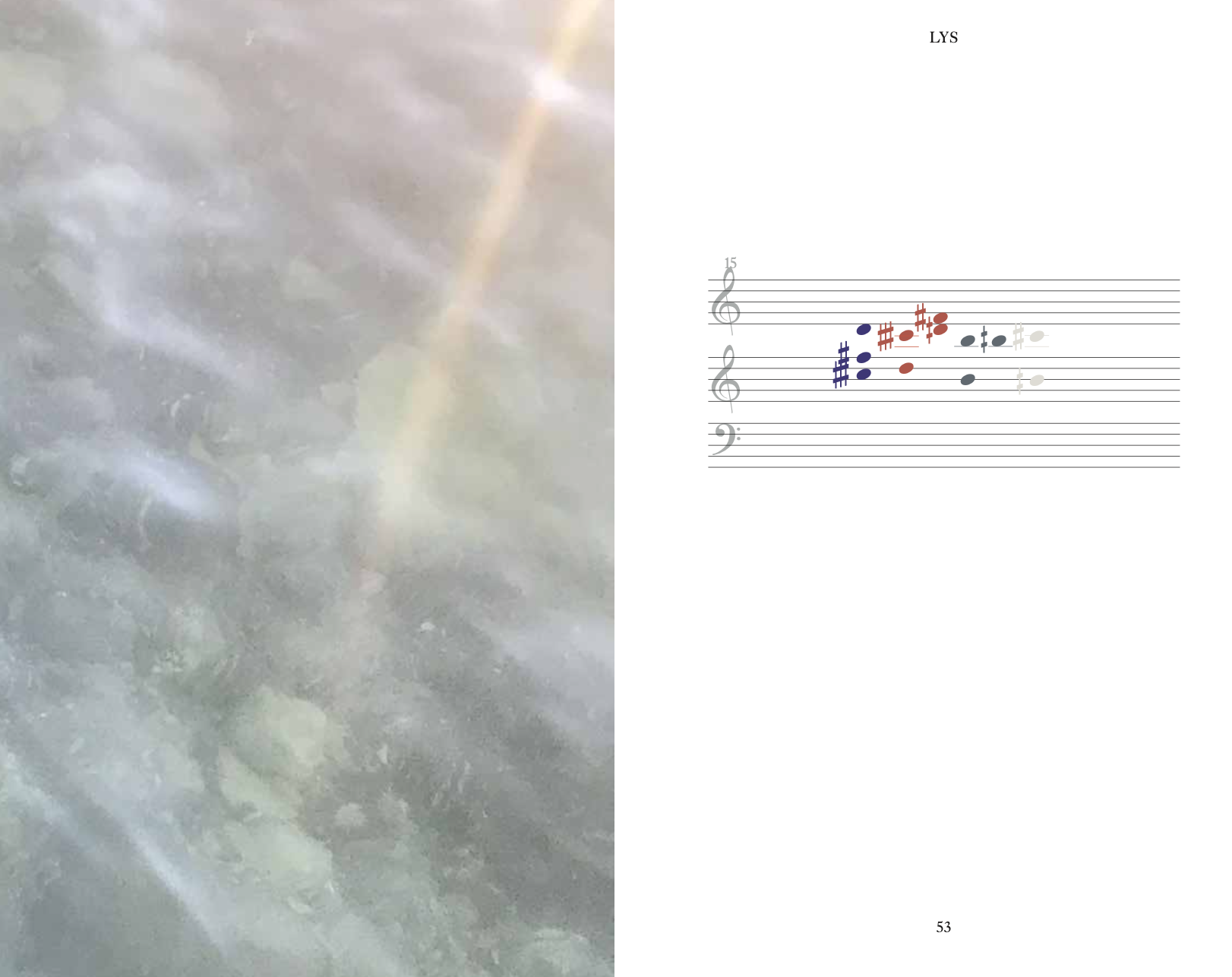

The piece begins with three chords from the chapter "LYS" - warm, radiant chords that contain something floating and pulling at the same time. They are divided into arpeggios and sustained tones. In this composition, it was always important for me to consider the sculptural structure of the orchestra. What happens in the left half of the orchestra (the high registers) and what in the right half of the orchestra (the low registers)? Here, on the far left, there are only sustained tones - so little movement in the arms of the strings. Violin II, viola, and cello play arpeggios and sustained tones, and the double basses on the far right only play arpeggios. Facing the large instrument, they embody the greatest physical movement on stage and stand in contrast to the first violins.

The translation into MIDI sounds (here with samples from a Steinway grand piano) I will only demonstrate once, but it is important to hear it once, as it becomes clear that the spectrum of the recording is very quiet and will be much amplified in the final orchestration (the angelic figure in Sally Mann’s Perfect Tomato).

Here I divide the orchestra into right and left, initially quarter by quarter in the bars 5, 6, with audible and visual wings - arpeggios across all 4 strings in the string sections. Then in three measures, the moving wing is in front in the strings and is only realized in terms of tone material through ascending and descending 32nd note chains. Following that, two measures, front and back. Here, the low strings already serve the function of visual movement, through arpeggios across all four strings, while the high strings remain in their 32nd note chains and thus physically remain calmer. Upon reaching bar 12, now all strings become physical wings by playing arpeggios across all four strings while the woodwinds play the 32nd note chains. In bars 14 - 16, the outer desks on the right and left become physical wings through arpeggios, and the rest of the strings blur the structure through various bowing speeds and sustained notes. The musical arc concludes with a physical wing to the left side in the high strings and sustained notes on the right side of the orchestra, supported from behind by the wind instruments.

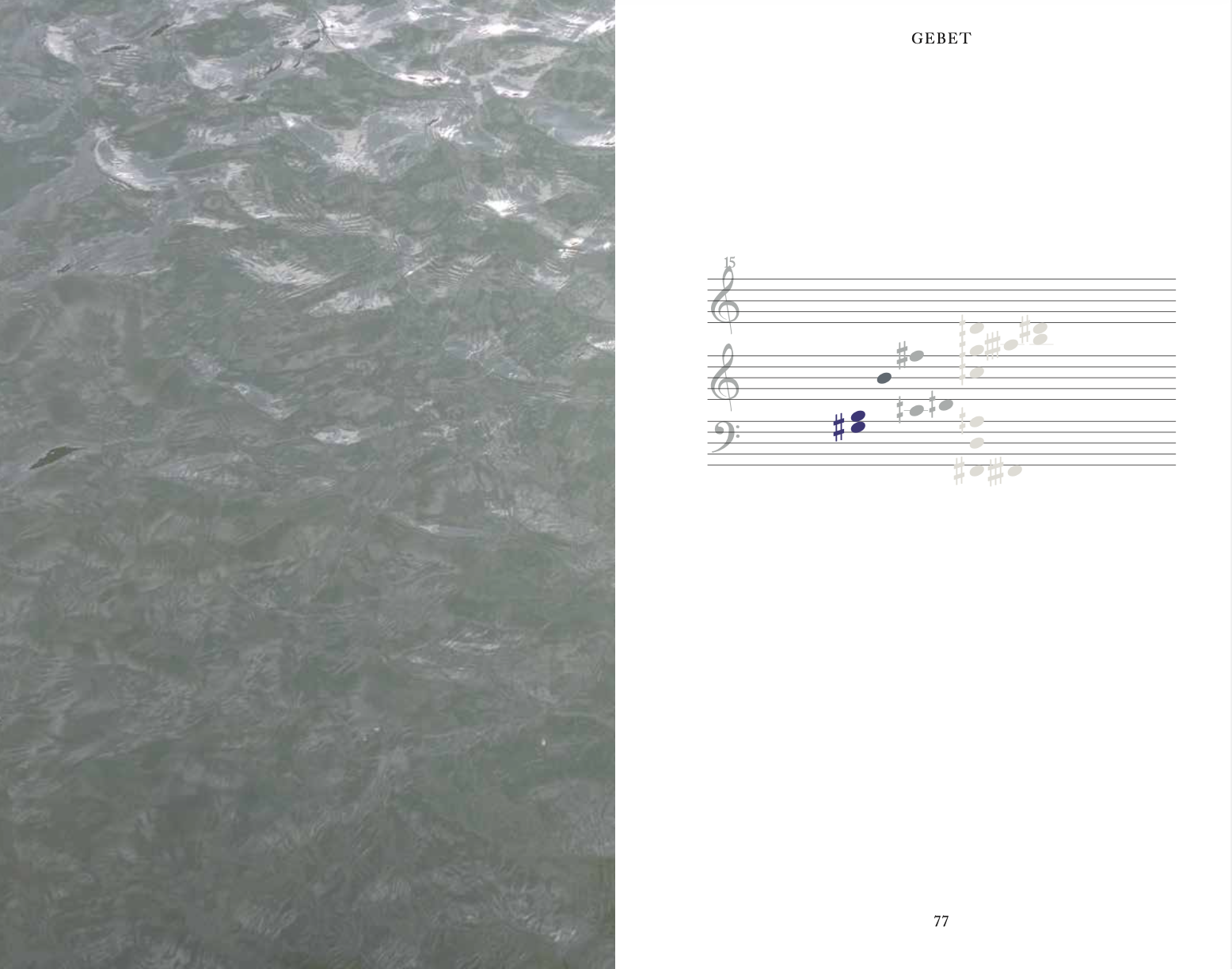

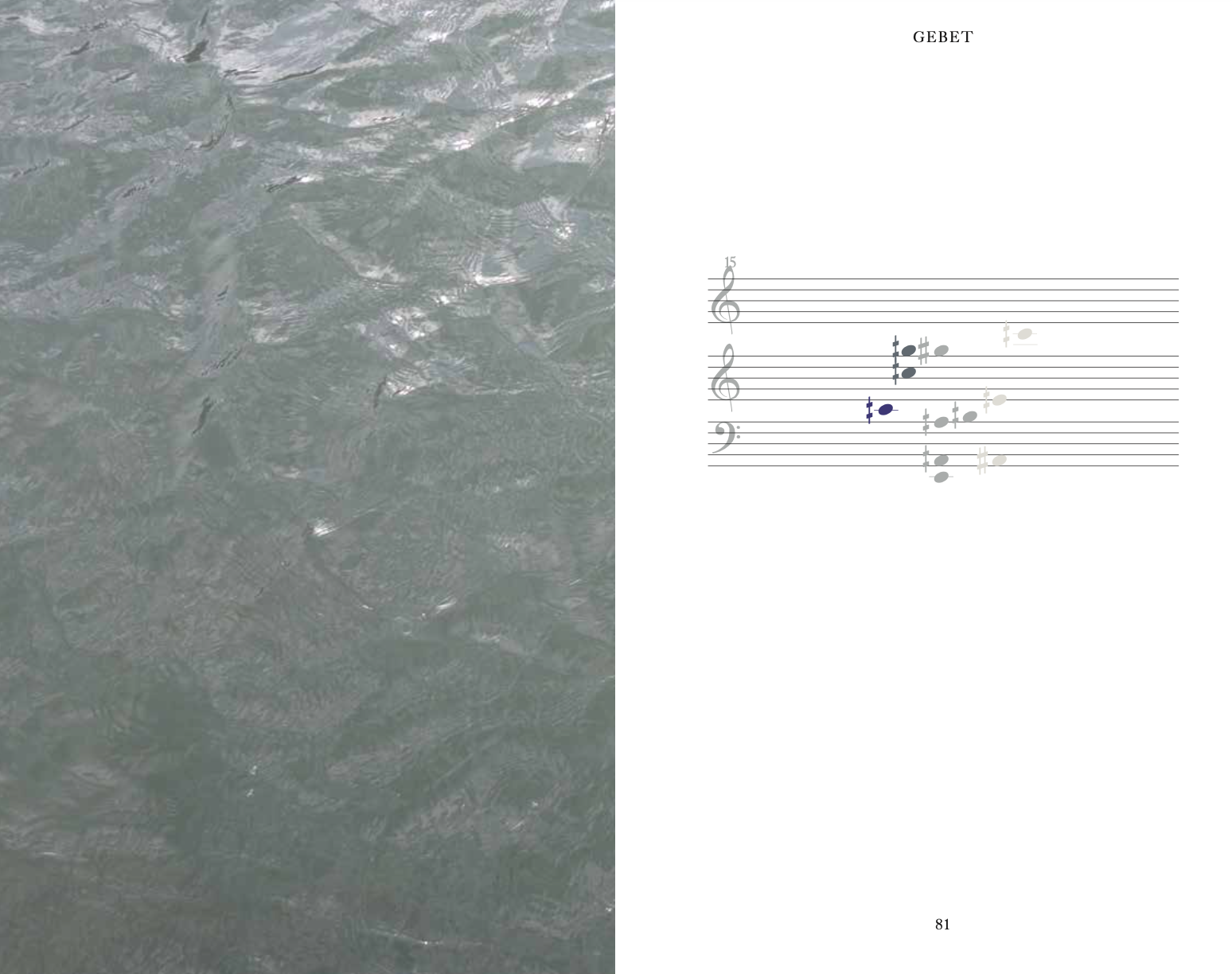

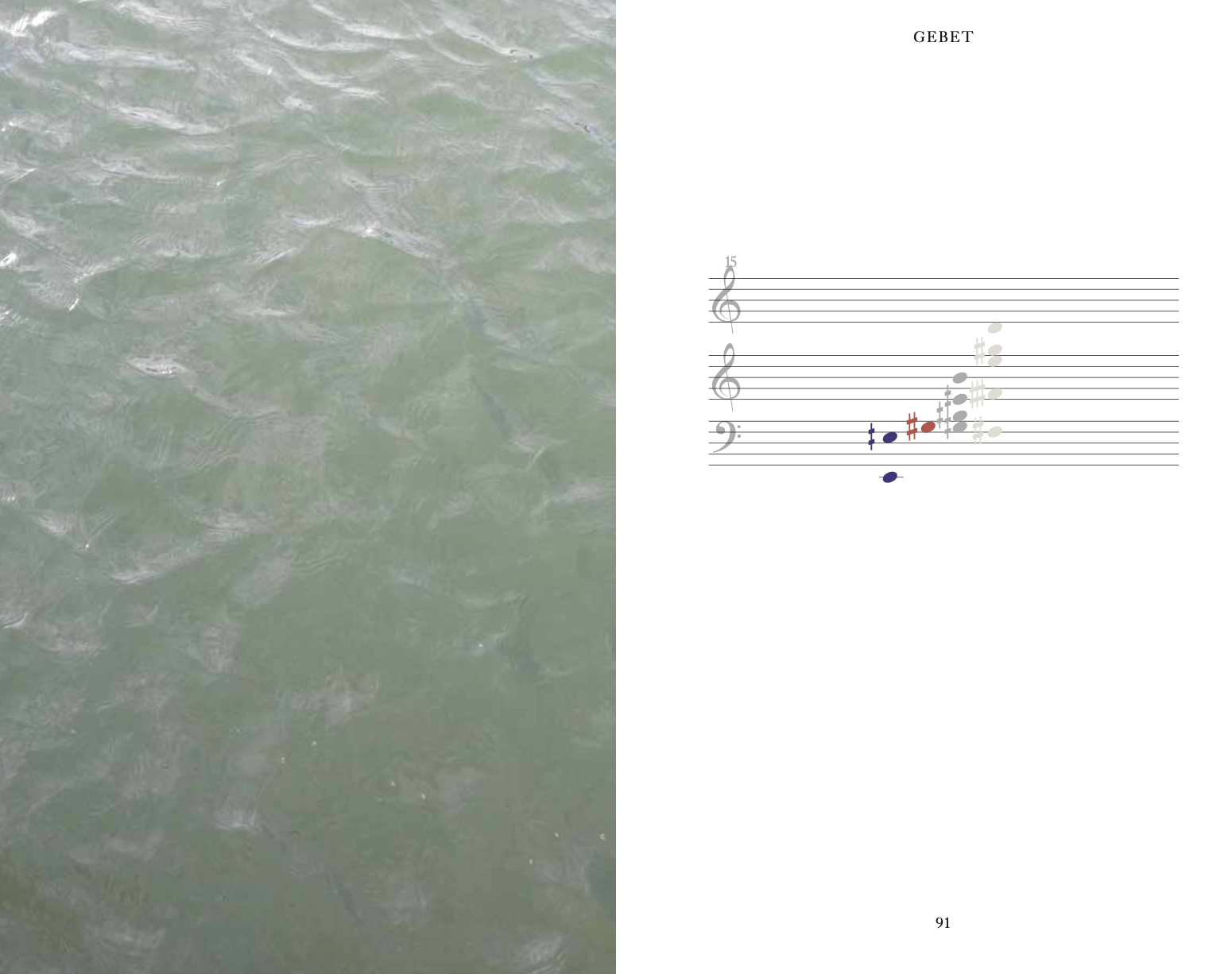

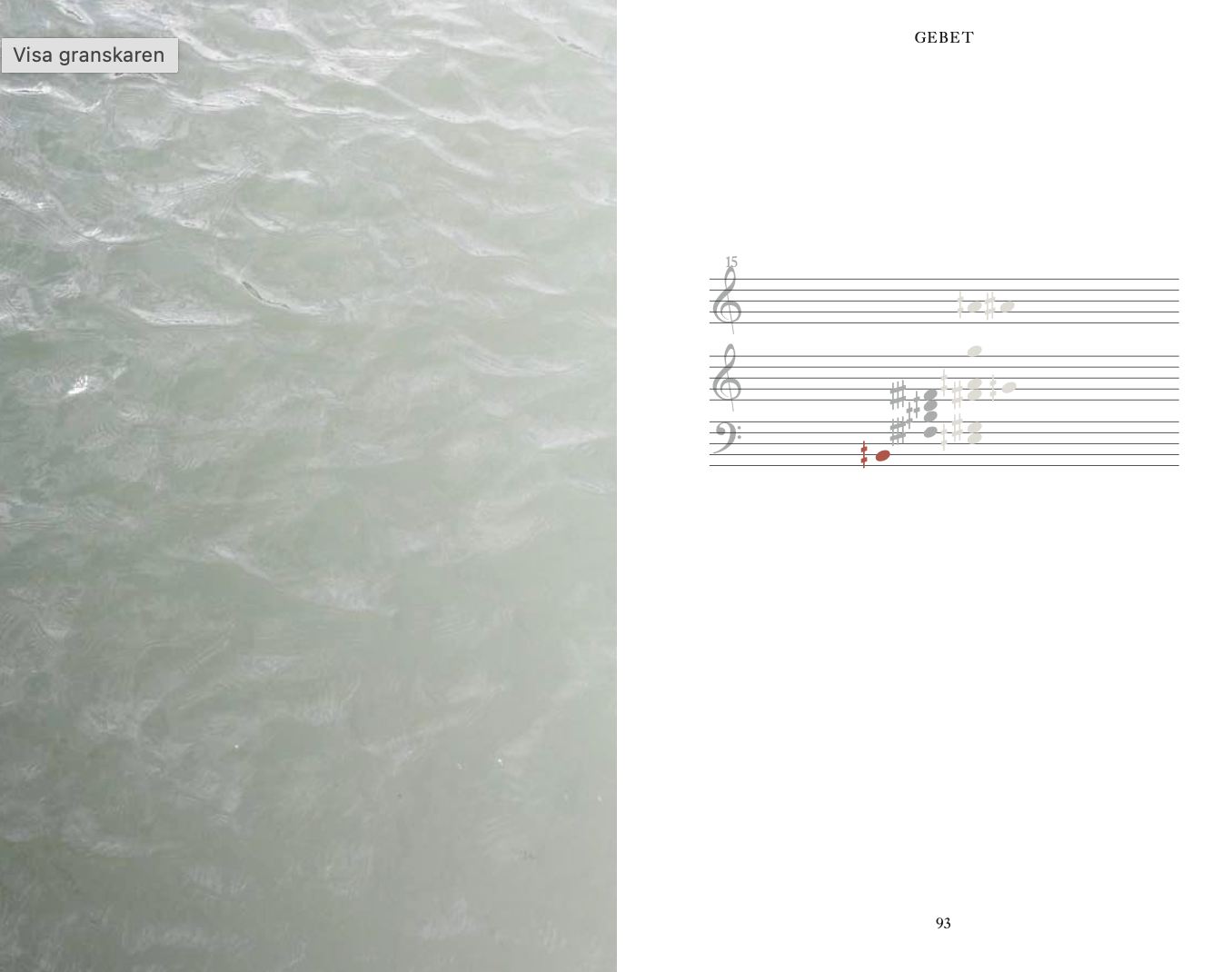

The following is the first section, which relies on a continuous floating harmony. A harmony that rests within itself and simultaneously floats in my ears. All these statements about expressions, of course, have no general validity but are my subjective perception. The chords from "GEBET" are paired with a simultaneous counterpoint that meanders between the first desks. Initially, one after the other in a circle, 1st violin, 2nd violin, viola, cello, later crisscrossing through the desks. The counterpoint is in the register above the chords.

Following from the same chord group are two standing, almost naked chords without embellishment. The main notes are reinforced by tuba, horns, and clarinets. In the strings, the most important main notes are doubled or tripled, and all the shades of gray are singly occupied. In contrast to the original recording, there is an amplification of the spectrum here.

I use the same chord as in bar 95 later in a completely different context. And the expression becomes entirely different. Here, I split the chord into the lower half and the upper half. The lower part of the chord plays on beats one and three, while the upper part of the chord plays on beats two and four. All notes are played with the same volume. Furthermore, I transpose notes from the lower half of the chord upwards. So, I manipulate it and distort the spectrum. What emerges is something that is entirely different in expression. However, in my opinion, the persistence and tranquility that fascinated me about this chord group are still inherent in the chord.

Consciously precarious moments occurred in the choreographic conducting of this piece. This occurred occasionally on individual beats or over several bars. In the first example, the conducting moves from right to left and from left to right through the strings in forte dynamics, with an attack from the right by the piano and an attack from the left by the harp, starting at quarter note = Tempo 130 with a ritardando to quarter note = Tempo 100. The register is relatively low for this effect, and I have learned that the movement is more noticeable in a high register.

Below I'm showing an example of an older piece for string orchestra and 2 percussions - MANTEL (2018). In this piece, percussionists whip the movement into action from the right and left. The tempo is 120 and the dynamics are loud. So, it's actually written very similarly, just with a different register. The result of a movement of sound through the orchestra is much more perceivable in the high register I believe.

Andrej Tarkovskij

Still from "Ivan's Childhood" 1

1962

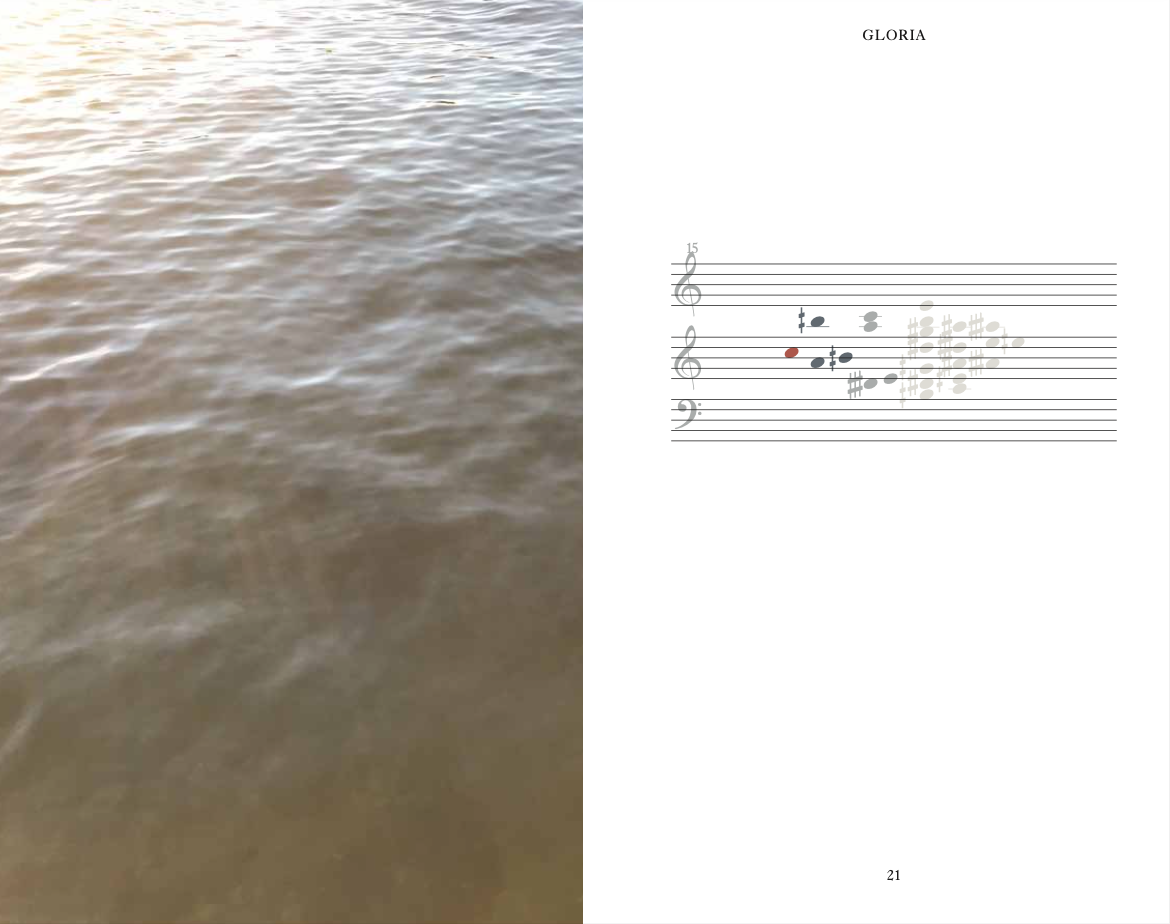

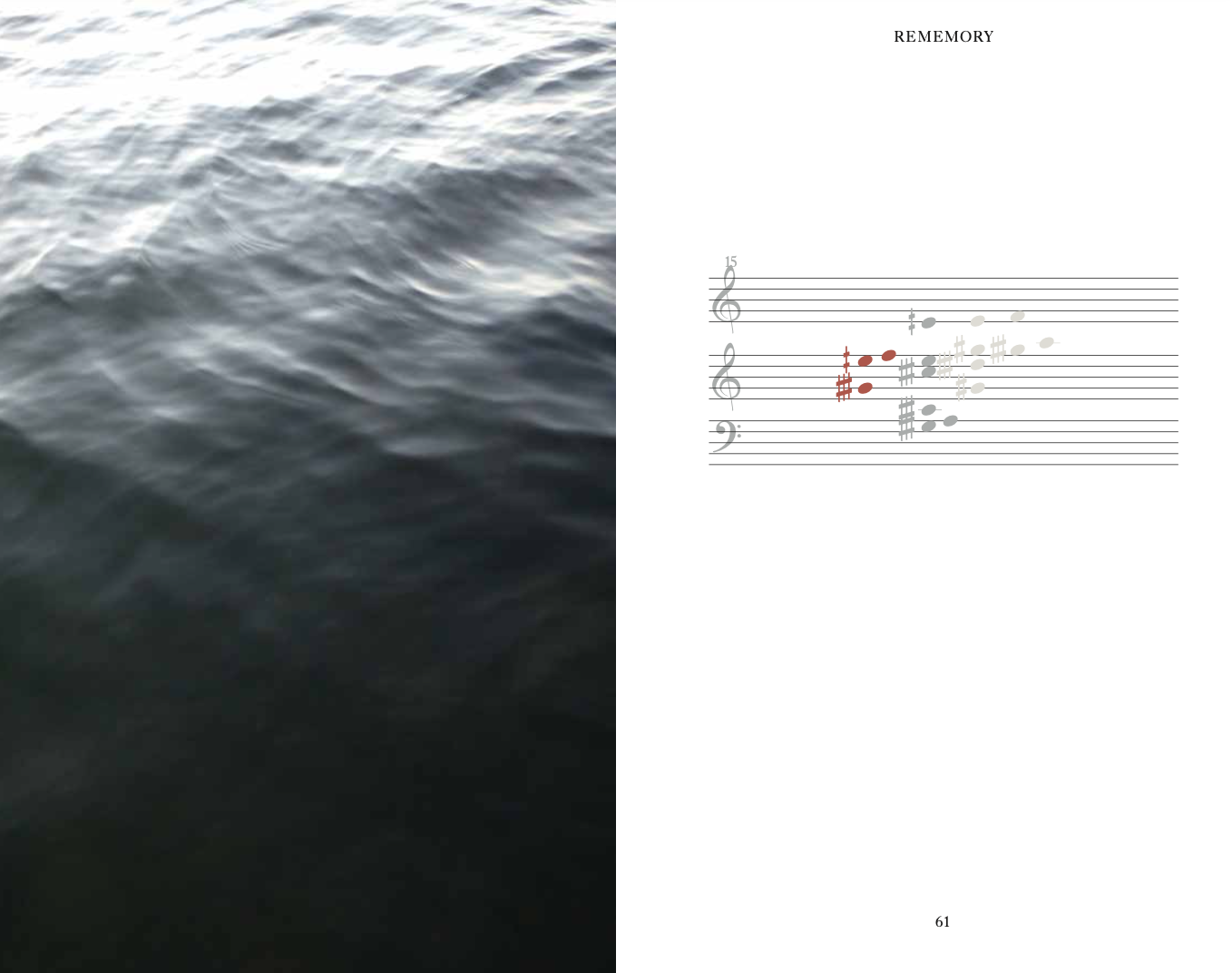

I thought of the above image from Andrei Tarkovsky's Ivan's Childhood (1962). The soldier kisses the woman while holding her above a trench. She floats, is pulled/held, but the possibility of falling is inherent to the situation. There is a simultaneity of pulling, floating, and falling characteristics in this image that I wanted to translate. In doing so, I drew from the characteristics of the chords in the chapters "GEBET", "GLORIA", and "REMEMORY", which in my ears strongly amplify each other in their expressive power.

The strings play pizzicato spectral chords. Only one instrument plays the main note for each chord, with a different player for each chord, not just in the first desks. It is precarious to get all this together and hear the harmonies; due to the dryness; the harmony, the strength, and the brilliance of the chords begin to crumble. And the chords become for me something very conscious, imperfect and fragile and with that in a way the simultaneity of pulling, releasing and hovering is somehow there in the concerthall I believe.

NEROLI is essentially an inventory of the orange blossom and its essences - the oil extracted from it and the hydrolat as a by-product. Two substances that, in my opinion, smell very differently. The oil is rather heavy and dark, reminiscent of the surface of oranges, while the hydrolat is so fine and floating, evoking a sea of images of lightness and brightness. It's about the violin as the main character, either bathing in the two different substances, sinking into them, or floating on them.

In the bars 194 - 232, I let the violin bathe in spectral chords.2 This means it plays the most important main notes of the chord and is usually situated in the middle register of the chord. It is not, as so often, clearly audible in the register above everything else. Instead, it must either surrender to the bath or engage in a certain audible struggle for presence.

Here, I would like to add something about the precariousness as a composer when writing and expecting very detailed dynamics and frequencies in a large chord of up to 32 tones. Exploring spectral chords is not always obvious. The score can be interpreted differently, especially with smaller formations like in NEROLI (1 1 2 1 - 2 2 0 0 - 2 Timp. - 6 5 4 4 2 ). For instance, in the first chord of bar 194 - 197, a distinction must be made between mezzo piano and mezzo forte, both dynamics that can be interpreted differently from musician to musician. In the second chord, distinctions must be made between mezzo piano, mezzo forte, and forte. Depending on how these differences are executed, different soundscapes emerge. Additionally, playing quarter tones can vary greatly from orchestra to orchestra. Especially with chords derived from a major chord, for example, orchestral musicians tend to adjust and play in tune. I find this particularly precarious because then the chord slips into superficiality and mutates into an expression opposite to the one I intended. The conscious chord, aware of its mold and expiration date, then sounds freshly born, as if it had never existed, and is unaware of its history.

The larger the orchestra's instrumentation, the less one is exposed to these possibilities. Then, the entire chord can be written in the same dynamic, and the main notes can be multiplied, providing a more secure representation of the dynamics.

In my opinion, there is also a certain beauty in this possibility of failure. The piece will show several different faces, stand in different lights, and thus gain a bit more autonomy and life of its own. This is something that is very dear to me, but it also entails accepting a loss of control, especially when one cannot be present at rehearsals.

PRECARIOUS MOMENT

In the cadenza, the strings play very softly spectral chords, the timpani occasionally provide fundamental tones, and the violin plays derivations from Schumann's "Im wunderschönen Monat Mai" by Robert Schumann (1840).

Essentially, the violin and timpani form a chamber musical unit; it would be beneficial for them to play without a conductor in order to truly be together and give the violin the tranquility it needs for this passage. The strings, on the other hand, need the conductor for the entrances of the new chords. Unfortunately, I could only attend one performance, but here a problem of expression arose for me because the musicians on stage needed different functions but all had to function under one. Tranquility was essentially only given to the strings through conducting, whereas the violin and timpani lost some of their tranquil expression as a result.

Of course, one could argue that the violin and timpani could play independently, but my experience is, that when someone conducts, it's difficult for the trained musician to ignore them. Here, a precarious situation in expression arose, which was not planned by me and was not desired at that moment, as it didn't enhance the expression of the music but rather worked against it.

This means, conversely, that harmony, expression, and precarious performance practice must be thought of congruently so they do not cancel each other out but rather amplify each other.

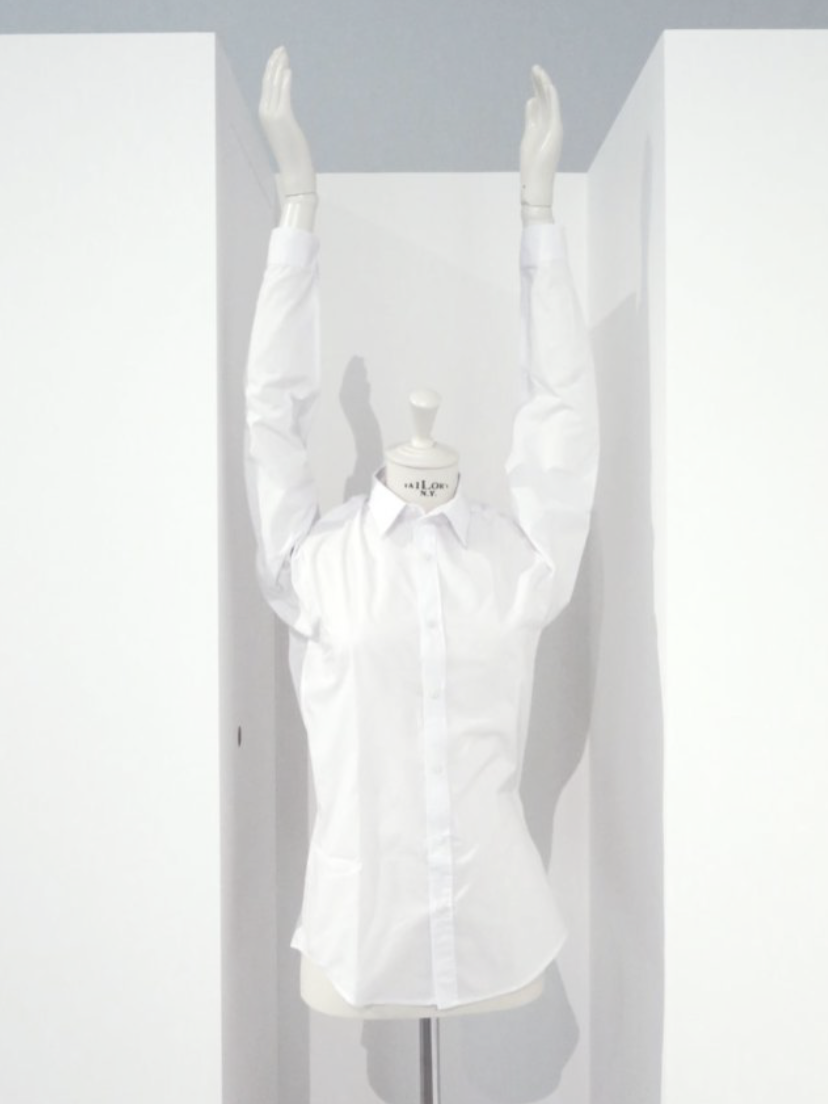

JUBELHEMD is a work that conceptually engages with the artwork Jubelhemd by Markus Schinwald. Jubelhemd depicts a specially constructed shirt where the wearer can only wear it with arms raised in a jubilant gesture; a forced jubilation. The piece is written for the 250th anniversary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. In a time when, due to the pandemic, it has been forbidden to collectively play music or listen to music together, it felt problematic to compose a piece of jubilant character. The piece contains numerous jubilant moments, but they always contain a contrasting element at the same moment, so it never really succeeds to jubilate.

Moreover there is the division of the formation into three groups - the left and right sides of the orchestra and the quartet of soloists. I see the formation as "the picture within the picture within the picture." One or two of the groups can be in the foreground, or all three, but in different ways. What interests me here is what happens when contrasts of different expressions are superimposed. I want to explore whether they become simultaneously perceptible when placed side by side or if together they become something else.

Furthermore, the soloists, who are quite virtuosic in their own right I believe, have found themselves in somewhat undesirable situations, as they cannot shine in the traditional sense I think. The trumpet player, for instance, has extremely high registers but never sounds brilliant. The violist, on the other hand, has many notes at times, but they are hardly audible - instead, one sees their arm waving up and down. It's like a solo choreography, as I call it. The harp serves the function of the strings in this quartet, filling out more, than it could shine. And the percussionist mostly plays simple musical fragments. They could shine, but the material is straightforward simple.

In this regard, I've had very different encounters with musicians - for example, the violists initially played too loudly, and it took 2 - 3 orchestra rehearsals for them to grow into their role, realizing they were essentially marionettes. However, they all did a wonderful job consistently afterwards. The trumpet players were the ones who consulted with me the most - initially claiming this piece was impossible, but towards the end, acknowledging that the trumpet part is essential for the expression of the piece - "one must embrace failure and accept that it is truly essential for the piece",4 as if they have the covert leading role. Meanwhile, the percussionist plays similar fragments with ease. These are small details of precarity that I compose here, but they are the essence of this piece for me.

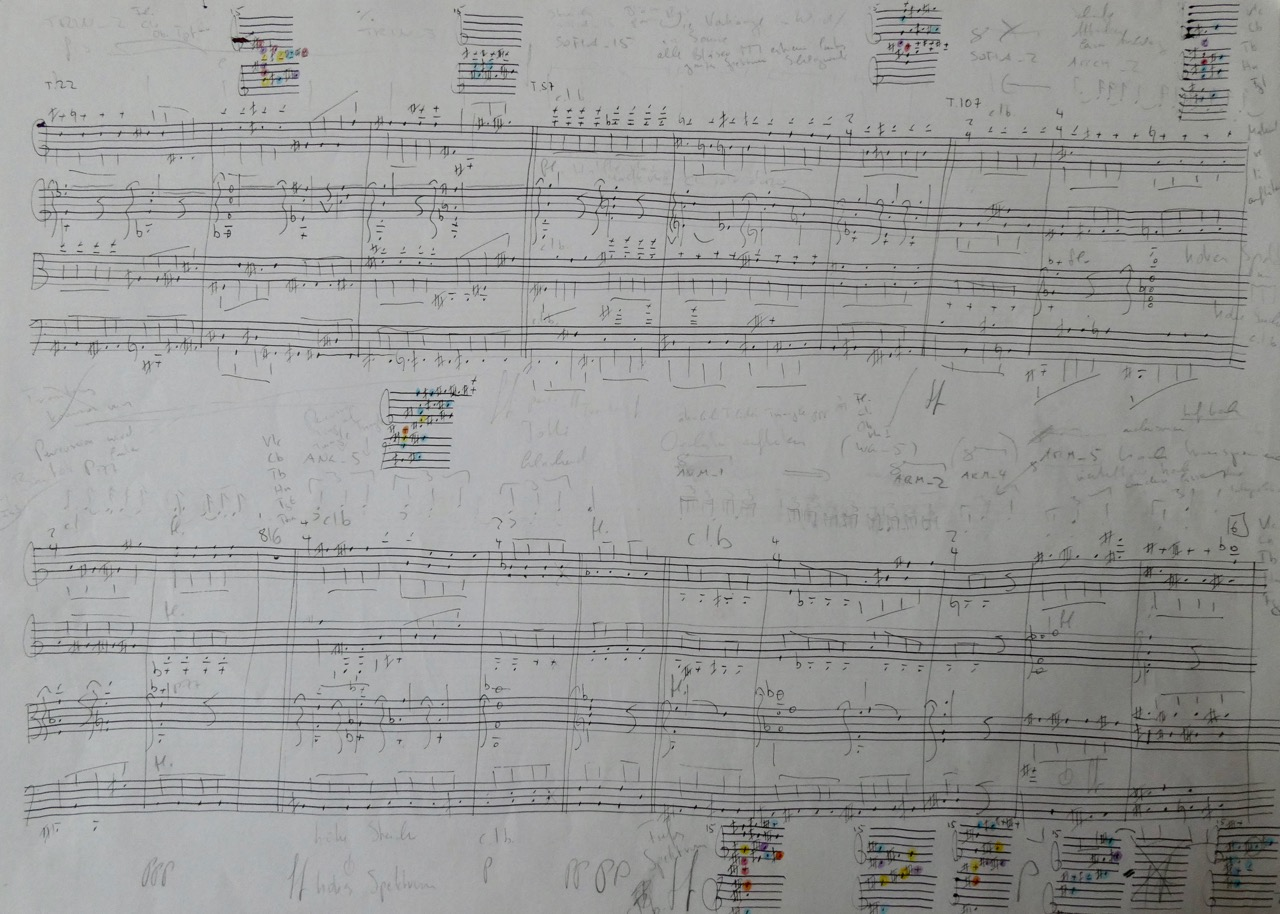

BALLHAUS is a piece about decayed plaster, relationships of dependency, and the question: if this were my last concert to attend, what would I want to hear? Never before has it been so clear to me how dependent we are on other people, as during the times of the pandemic - therein lies a beauty but also a brutality, if it is not desired.

It was important for me to physically incorporate this phenomenon into the music. There are various pairs of soloists who essentially cannot play without each other or are at least restricted in their sonic possibilities and movement.

There are two percussionists swinging on swings above the orchestra with small instruments and mallets. They can only produce a sound when they meet in the middle, as one is holding the instrument and the other is holding the mallet. There are two more percussionists on a seesaw in front of the orchestra. They can only play the timpani when the other player is in the air.

The clarinet and oboe are connected by a sort of trunk made of fabric, one of the two players performs movements that the other player forcefully, through the connecting trunk, must follow. And all this while they play glissandi in the highest register. A trombonist stands on a turntable and is essentially self-sufficient. But he only plays when the turntable is turning.

Furthermore, the orchestra is divided into two halves at the beginning and the end of the piece. Front and back are separated by an opera that casts a shadow theater from the musicians. There is another conductor behind the screen who does not coincide with the one in the foreground. One sees violinists playing in the shadows but barely hears them. Additionally, there is a sense of distance created acoustically by the orchestra behind the screen. Two times, it seems, sound simultaneously or successively.

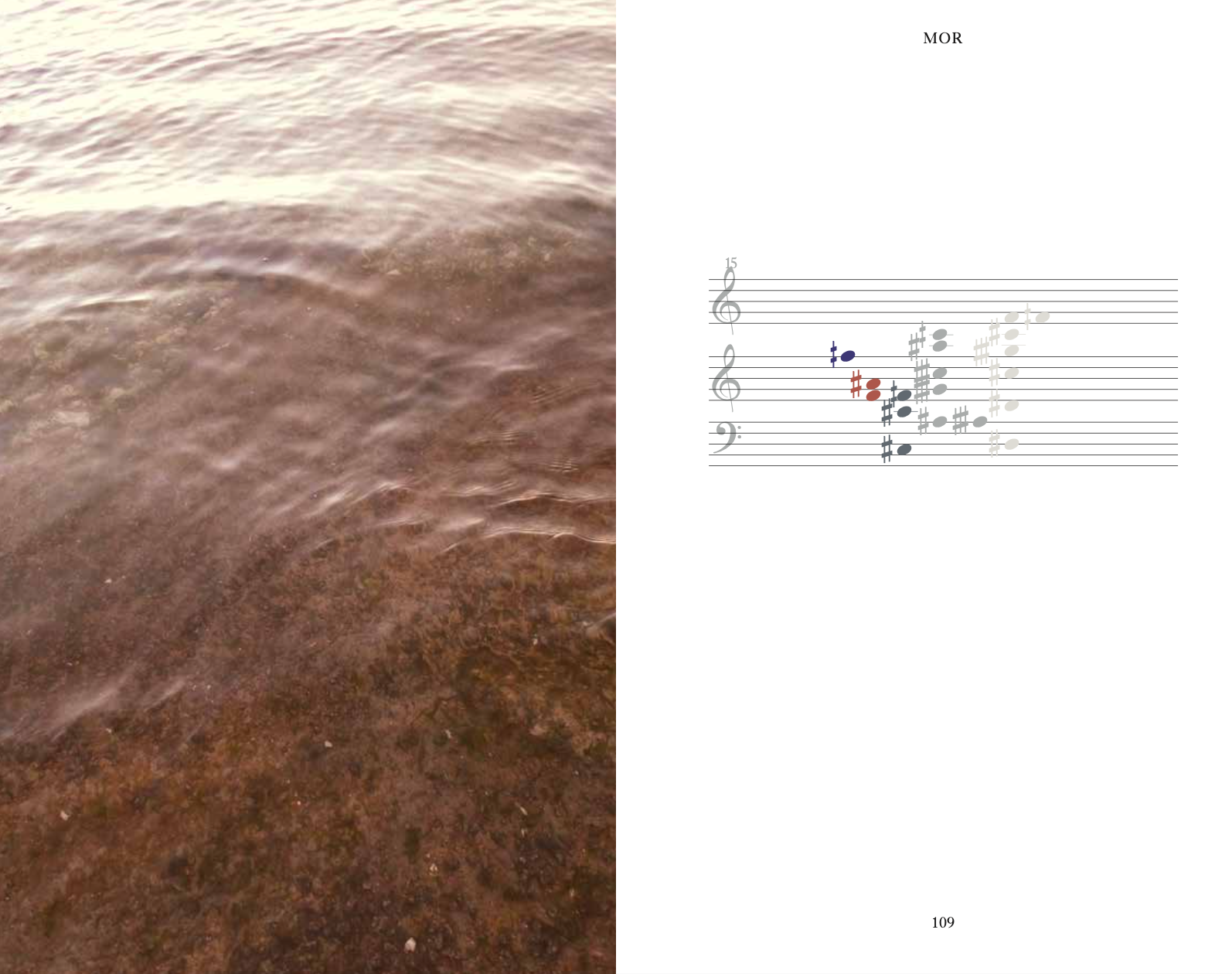

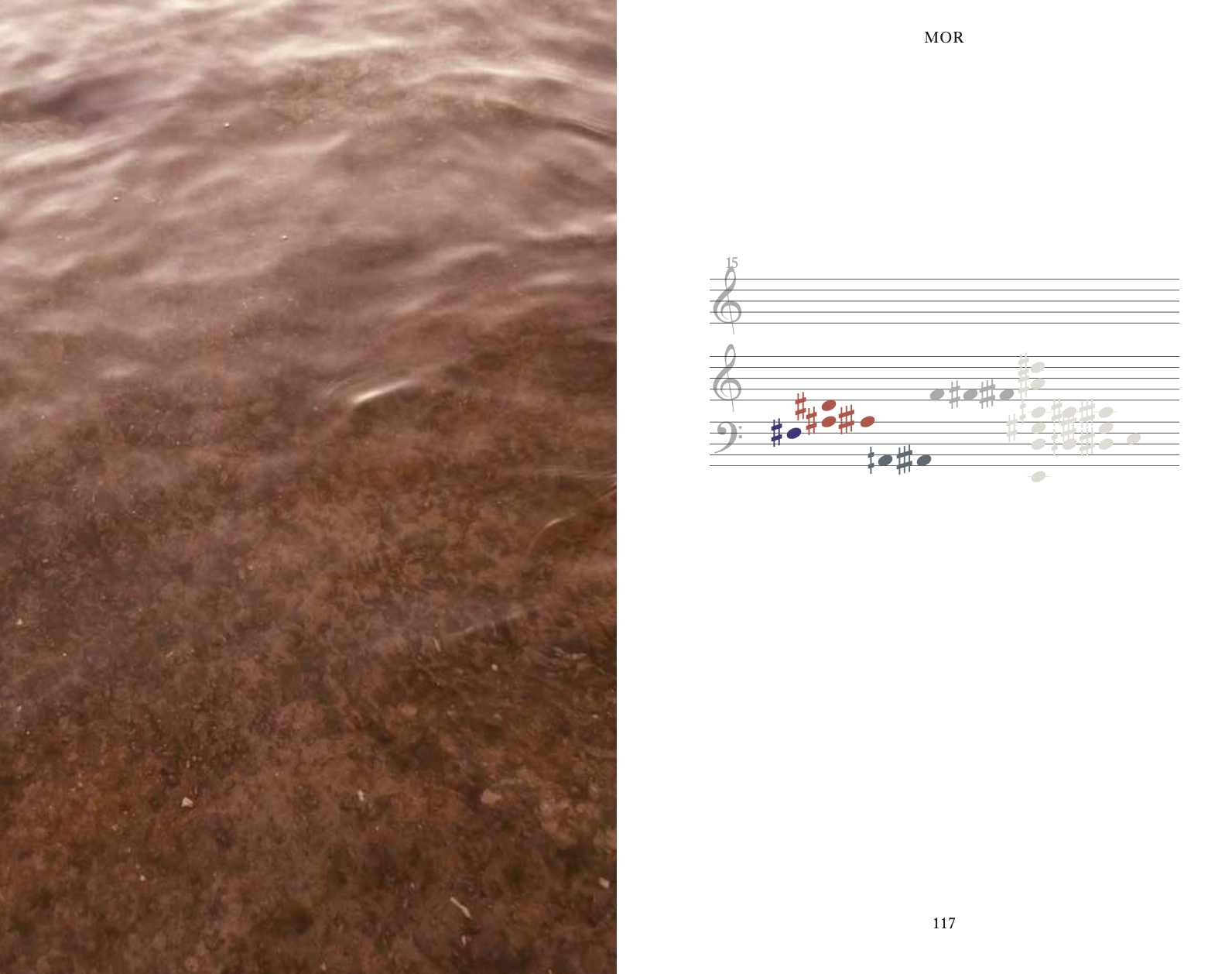

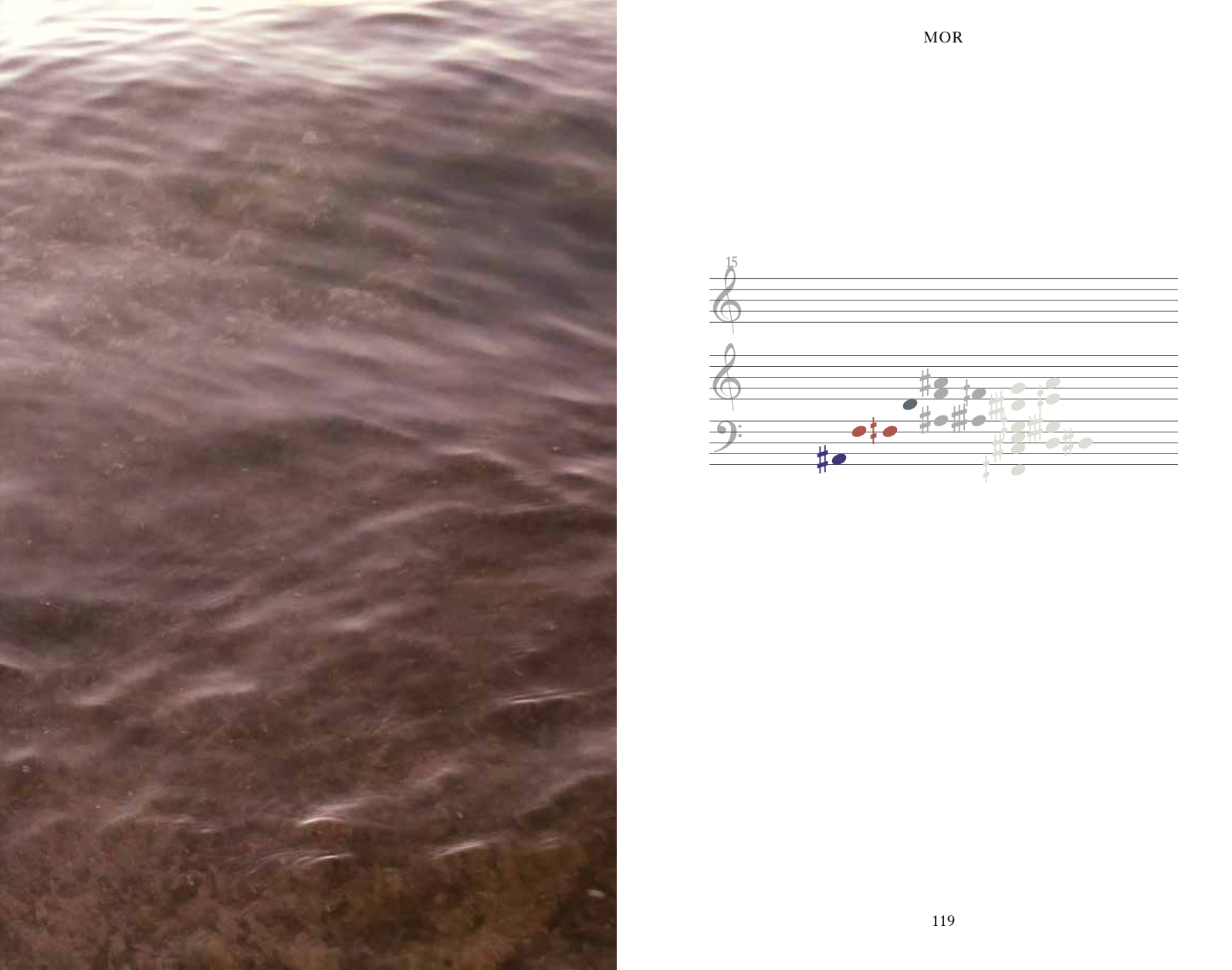

I employ here five different chord groups - "REMEMORY", "PRAYER", "GLORIA", "MOR", and "LES BAINS". For me, the form and harmonization of the waltz, paired with various expressions of the chords, are like a reflection on the richness of a life that unfolds in simple rhythm, celebrating itself but acknowledging its transience.

At first, all wishes we had, Markus Schinwald and I, seemed almost impossible to realize, but little by little, everything became possible. But what I quickly learned - basically, everything is possible in an opera house, but the time it takes to realize things is endless, it feels like steering a large barge on vast waters.

It was beautiful to collaborate with another artist. Unlike with an opera, I initially wrote the music, and Markus Schienwald added the props. The roles seemed almost reversed. As Markus Schinwald once put it: "The music was the film, and the staging was the film music."

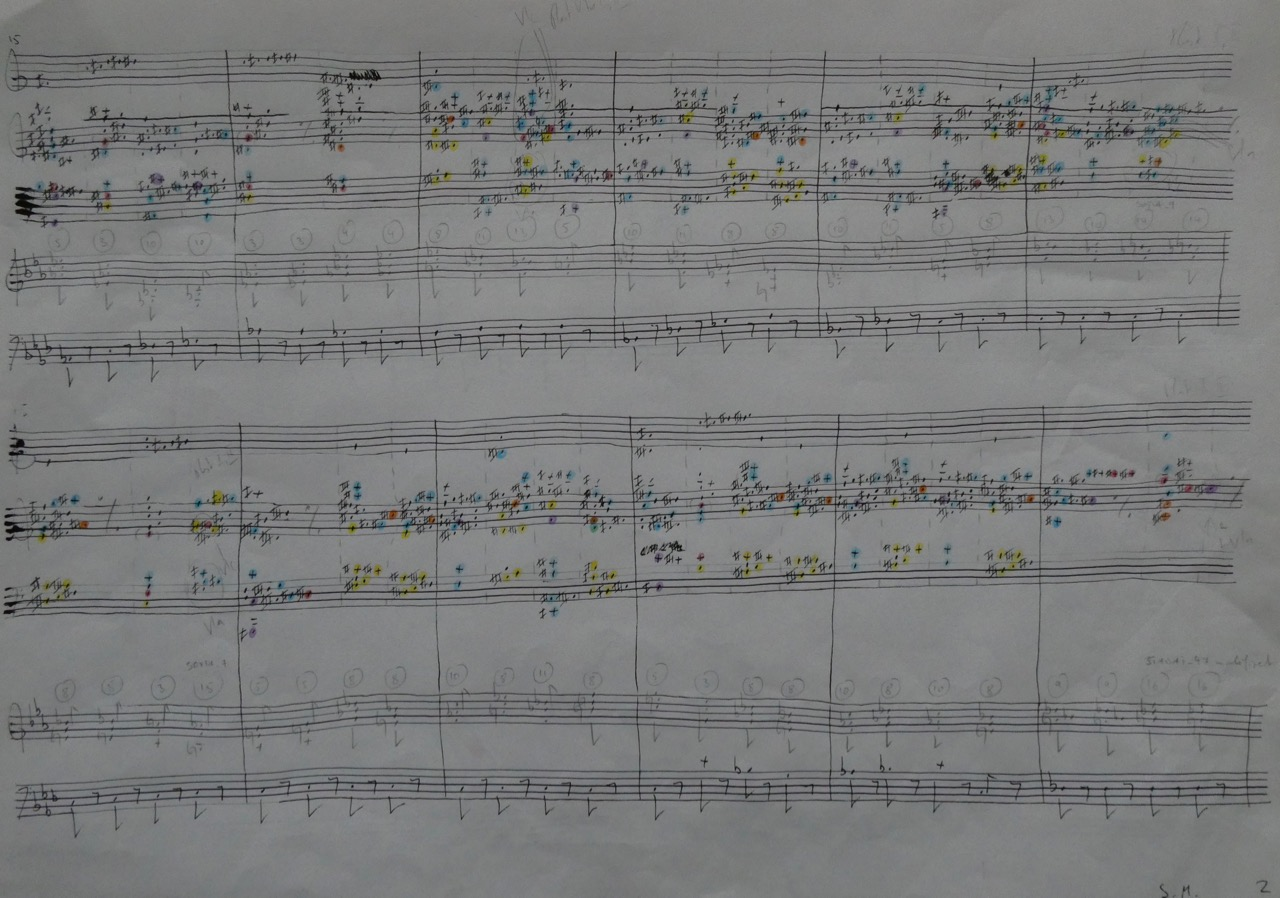

In ISHJÄRTA, the focus is primarily on two distinct chord characters - warmer ones and colder ones. On the one hand, there's the inner part of the heart, audibly pulsating. The chords here are very warm, compact, and strong. Surrounding this is an icy layer composed of chords that shield and are more emotionally neutral, possessing an almost tangible surface. Between these two realms, there exists a third space where ideally, another expression can emerge. I work extensively with registers - the capped, shielded world spans the entire spectrum, like a mist or an ice layer, with added material shimmering through or having to navigate its way through this layer. The inner, pulsating part of the heart exists simultaneously in the deepest registers and the highest heights, but not in the middle register. Thus, I attempt to create a sound space for musical material that can move freely and be clearly audible within this space, adding another layer of expression. My focus here revolves around the question of intensifying expression. Do the expressions amplify each other or cancel each other out? Do they change? Does the music become independent or does it remain in its components?

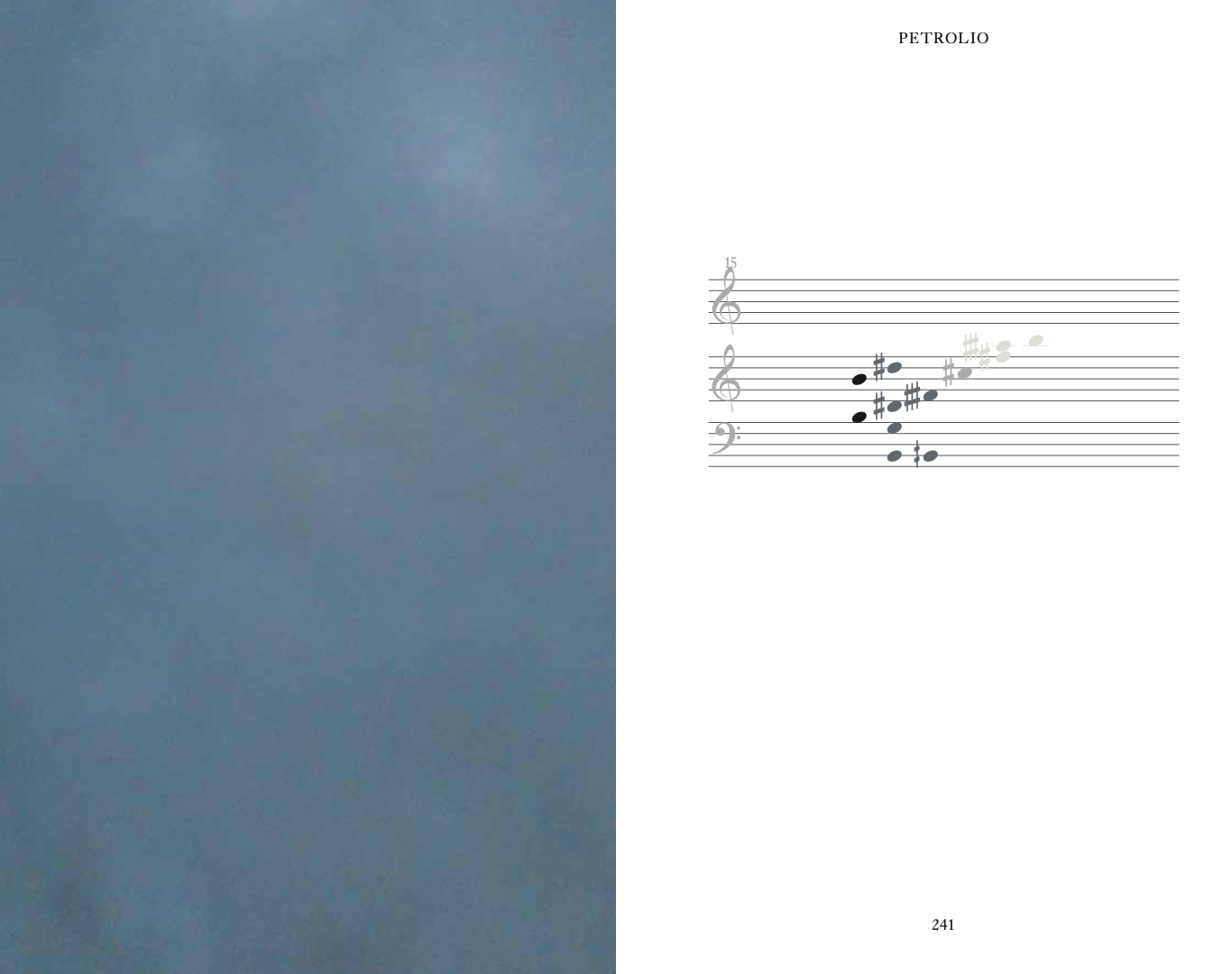

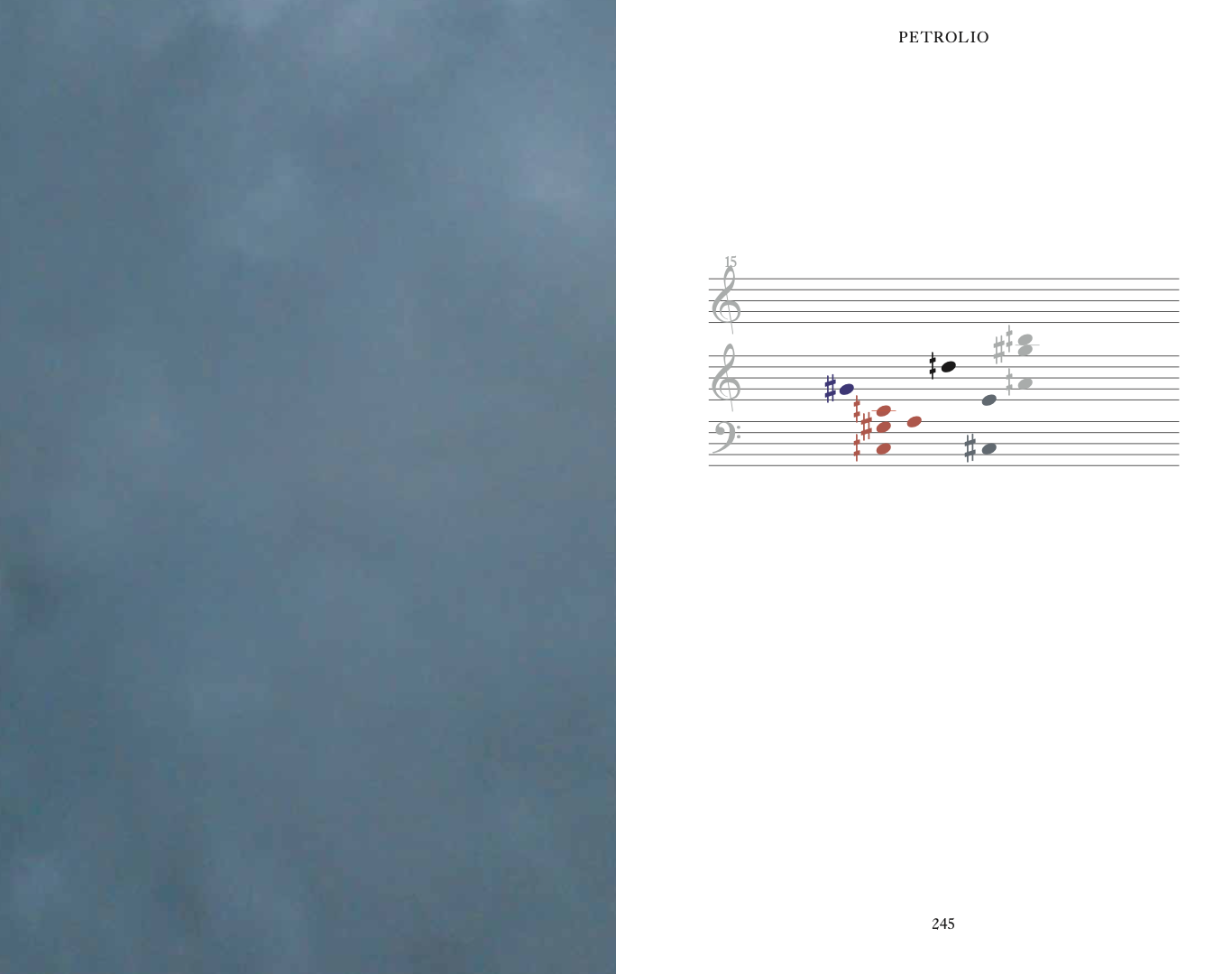

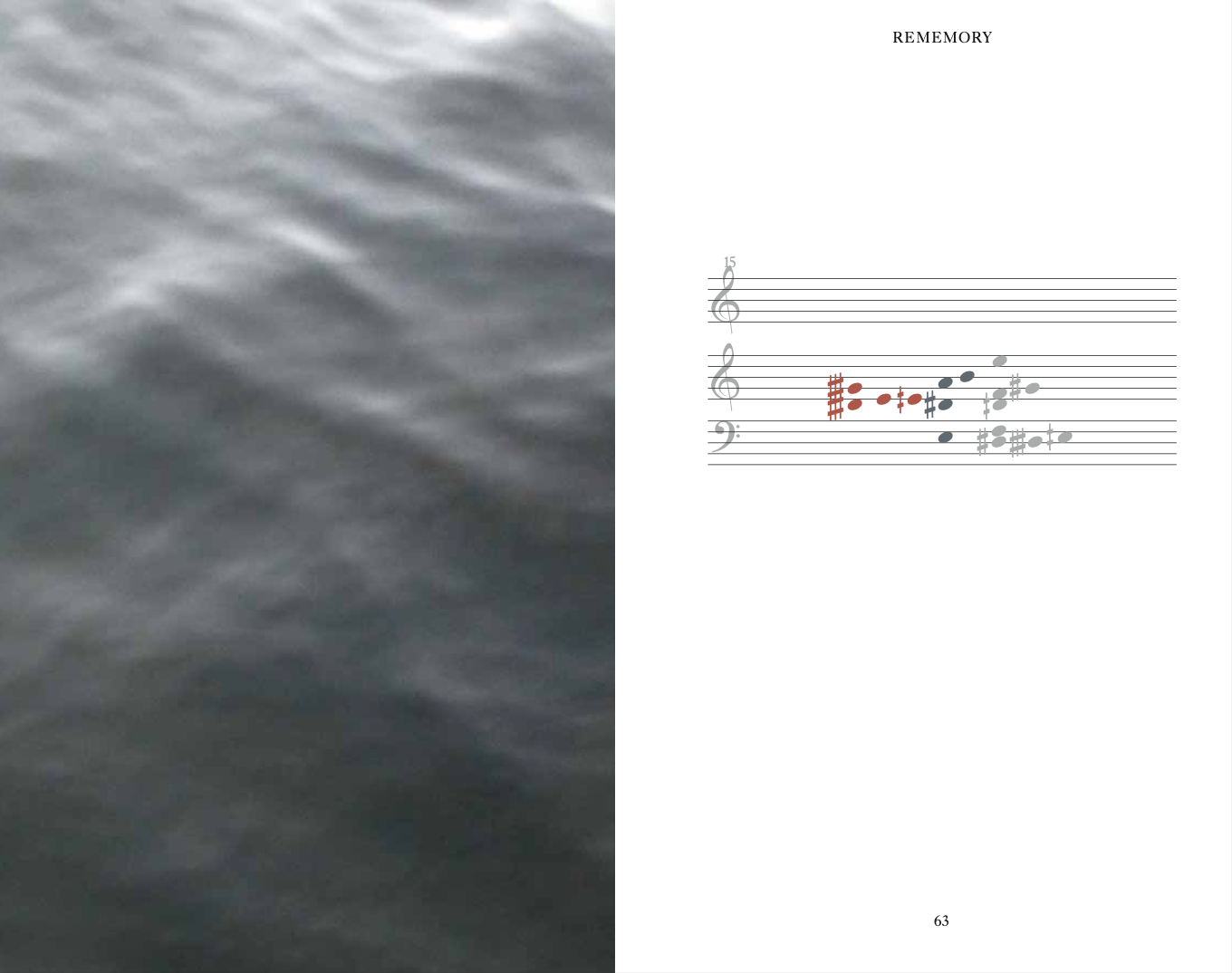

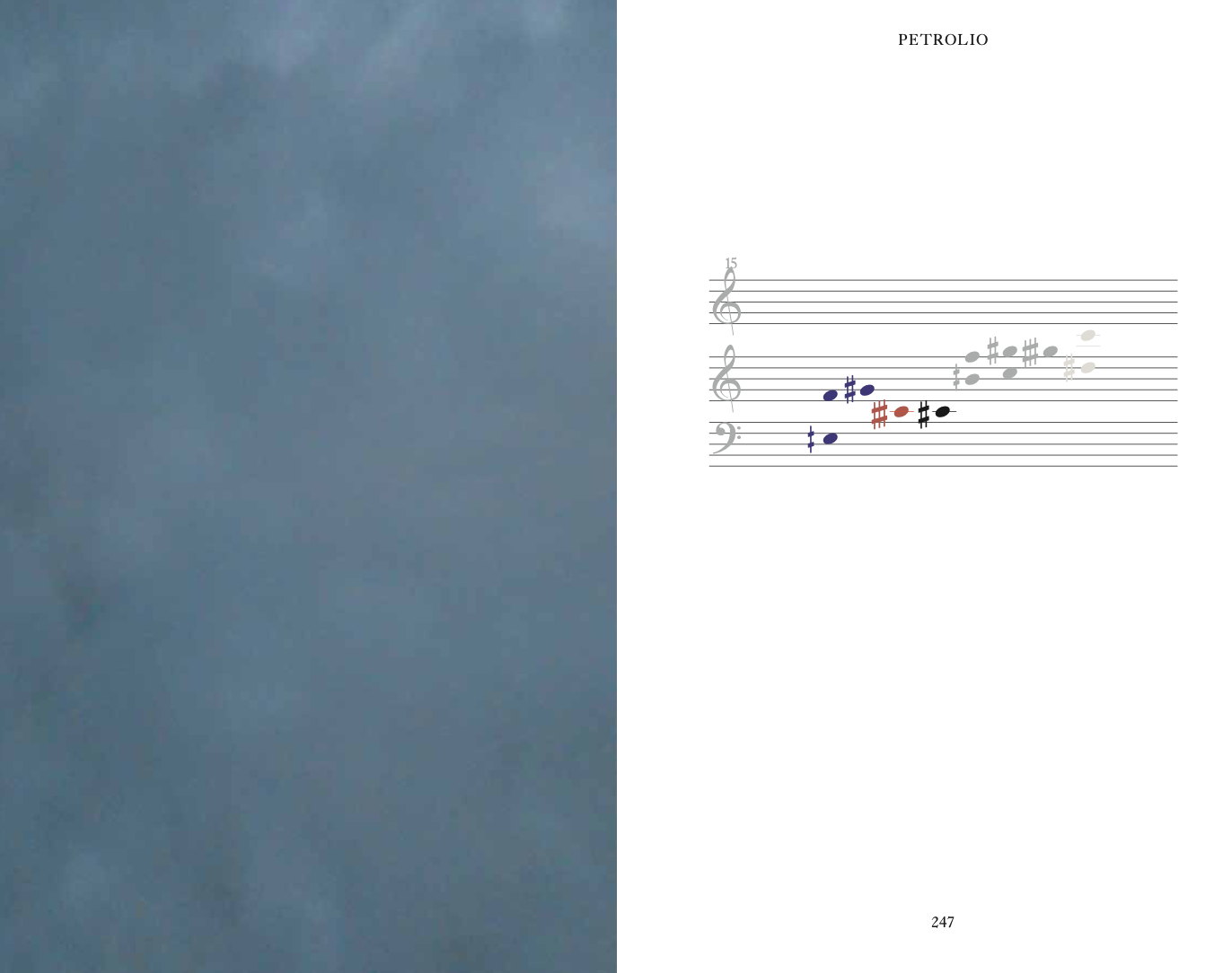

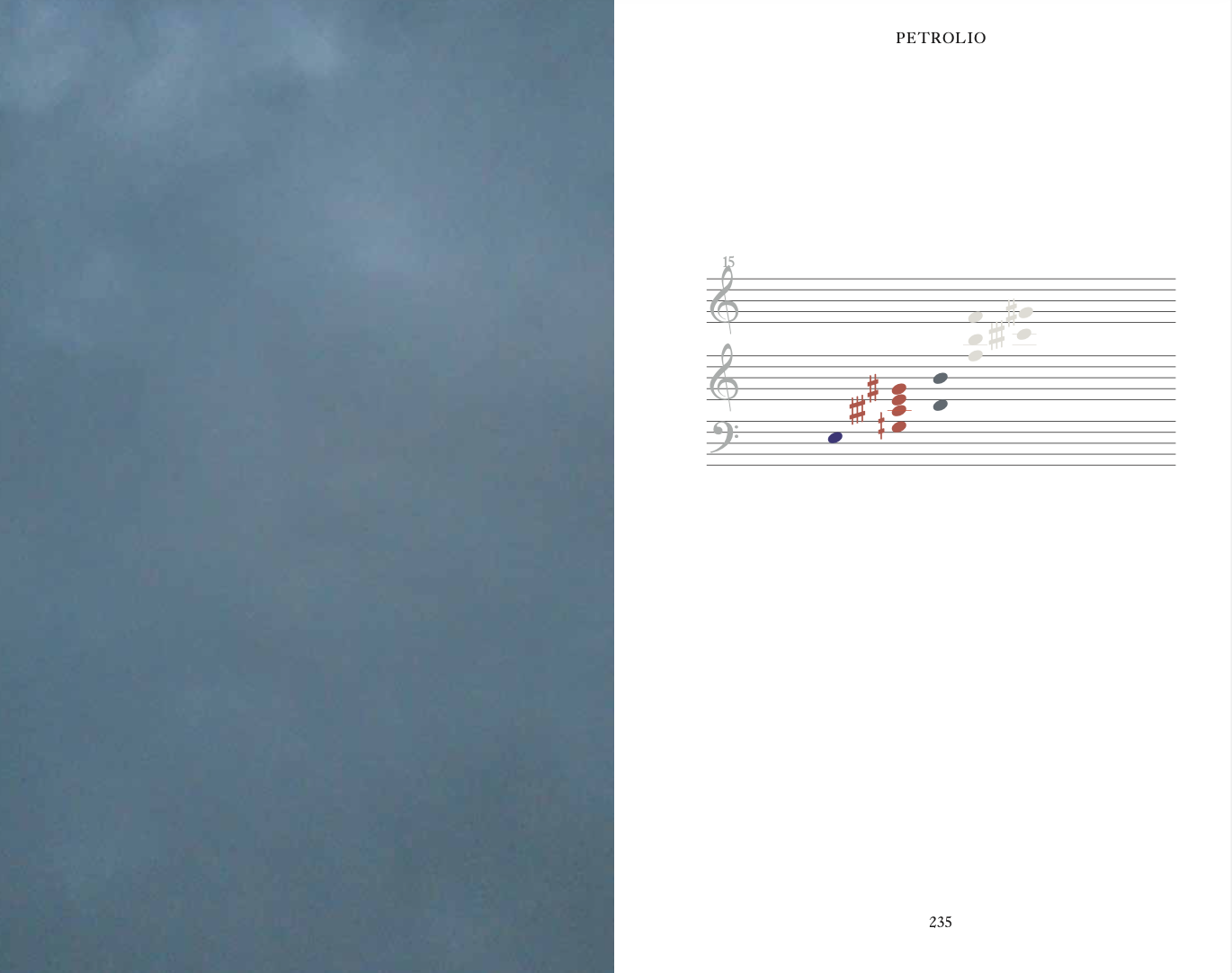

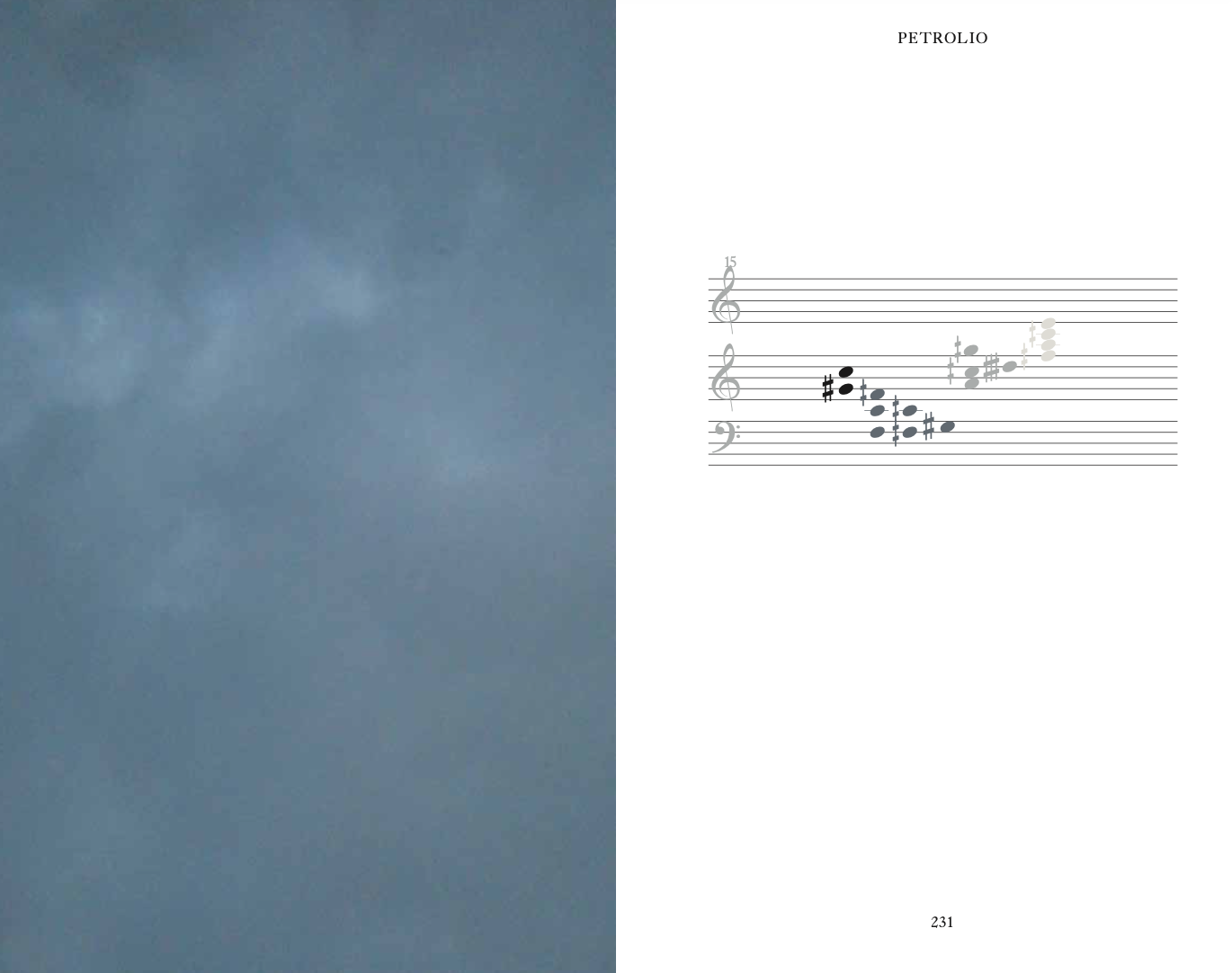

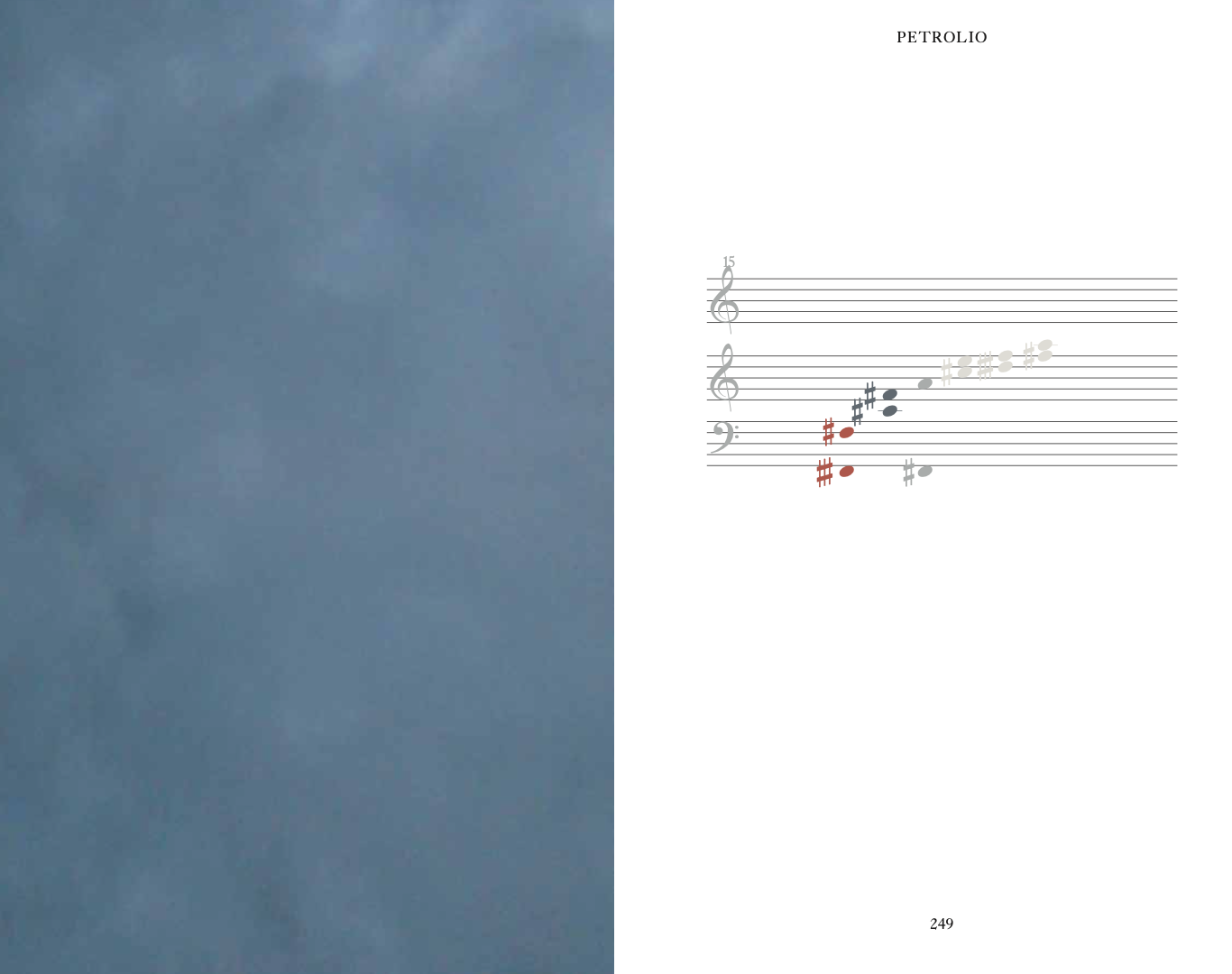

The piece begins with a layer of chords in the strings from the chapters "PETROLIO" and "REMEMORY". Despite their respective idiosyncratic expressive power, they form, in my mind, a sort of ice layer beneath, in which the musical material in the second violins moves, interrupted by a kind of harmonization in the rear desks of the string sections.

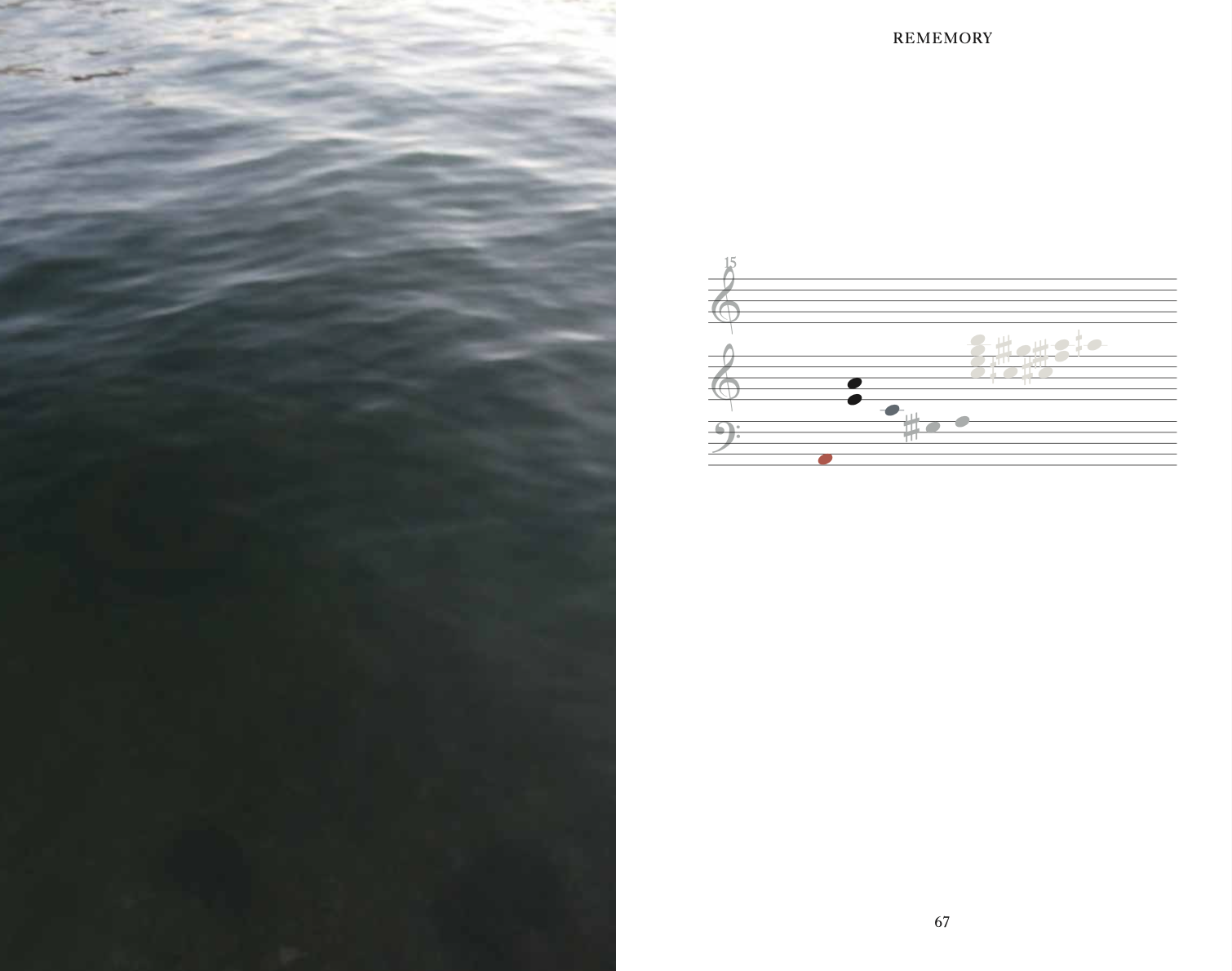

"PETROLIO" is a very special chord group for me because it brings a certain calmness and at the same time, harbors a fascinating lively relief in the overtones, which resembles an oil slick on water. It's a chord group that can be examined very craftily and structurally. The expression is not necessarily gripping. "REMEMORY" chords, on the other hand, behave very differently. They are so directly palpable and filled with expression in my ears, unlike any other chord group. They have something very immediate; one cannot escape them.

In these measures, I don't orchestrate the chords from bottom to top but rather try to get as close as possible to the expression of the main notes in the recording through the placement, playing technique, and positioning in the orchestra.

For example, in measure 1, I place the main tones of the chord in the double basses - because they are very high there and have fewer strong overtones, resulting in a weaker, paler, less radiant expression. Similar to the quality of the expression in the recording.

In measure 3, for the second chord, I distribute the main notes of the chord among different instrument groups. So, once again, I don't orchestrate from bottom to top. Instead, I want the main notes to sound embracingly from all directions.

The main notes of the chord are generally played ordinario, while the rest is played c.l.cr.

So I always try to adapt the instrumentation to the expression, be it sonically through the pitch, dynamically through the playing technique, or spatially through the orchestral layout. Furthermore, I attempt to juxtapose contrasting expressive qualities in the chord work so that they can mutually reinforce each other in their expressions.

In measure 14, I partially place the violas higher than the first violins. Additionally, I use a chord from a different chapter with a contrasting expression. All string players play c.l. or c.l.cr. The expression is completely different and would be less expressive, or at least less surprising, in its character without the preceding chords from "PETROLIO" and "REMEMORY" to set the stage.

I'm trying to create sculptures within the orchestra within these two chords. Musically, this is achieved through fast runs in the woodwinds and strings, as well as visually through high bow speed indications in the strings.

0 - - 1 - - 2 - - 3 - - 4 - - 5 - - 6 = indicates the velocity of the bowing:

0 = no velocity

0.5 = very very slow = approx. 60 sec. per bow (unstable tone) 1 = very slow = approx. 15 sec. per bow (stable tone)

2 = slow = approx. 3 sec. per bow

3 = medium velocity = approx. 1 bow per sec.

4 = fast = approx. 1.5 bows per sec.

5 = very fast = approx. 2 bows per sec.

6 = as fast as possible = approx. 2.5 bows per sec.

All numbers lower than 1 should result in an unstable, dusty sound.

No matter what the indicated speed is, the entire length of the bow should always be used. The indication ”6” does not mean a normal tremolo!

Additionally, the choreographical conducting begins, creating sound waves that move through the orchestra.

Measures 33 - 34: Brass, oboes, and clarinets, as well as the rear desks of the second violins, viola, cello, and double basses, follow the choreographical conducting. The first desks of the second violins, viola, and cello play arpeggios or long runs together with flutes, oboe, and Es-clarinet. They run simultaneously in opposite directions. The first violins have a string movement from 4 - 1, reinforcing the choreographic conducting moving from left to right with an accent and visual moment from the left side.

Measures 35 - 36: This is followed by a musically homogeneous crescendo and decrescendo, barely with a visual moment and without choreographic conducting.

Measures 37 - 38: All woodwinds now play arpeggios through the chord in opposite directions and tempi. The low brass is excluded. Otherwise, the handling is the same as in measures 33 - 34.

Measures 39 - 40: This is followed by a musically homogeneous crescendo and decrescendo, barely with a visual moment and without choreographic conducting.

The handling is similar to the preceding measures, but now choreographic waves from the right are also added. In this case, a string movement from 4 - 1 is written into the left side of the orchestra, in the cellos and double basses. This is followed by two musically homogeneous crescendos and decrescendos, solely with a visual element in the first desks of the first violins, viola, and cello. A softer, lying sound follows in measures 49/50 with a wing movement in the first desks. The following bars are variations of the same concept.

These two examples are constructed similarly to the piece FLÜGEL. Pulling - releasing - floating. However, here this only occurs on the visual level and not in the chord progression. here I did not select the chords based on their pulling, releasing, and floating characteristics, but solely sought chords with warm tonal qualities within the spectrum.

Lisa Streich

ISHJÄRTA

video excerpt from concert

8th of June 20235

Berliner Philharmoniker

conductor: Kirill Petrenko

In contrast to the opening measures where chords from "PETROLIO" are also used, here the chords are orchestrated from bottom to top. The intention is to create an undulating mass with less surface and relief character compared to the beginning. All instruments are utilized to the fullest extent in their most resonant registers. Within this mass, isolated desks move in individual counterpoints that lead from bottom to top and back down again, in tones specific to the chords and at various tempos.

In the last two chords (b. 178 - 186), the bow speed decreases to 0.3, which restores more surface to the chords, thus aligning them with the expression of the beginning.

With this orchestra and this conductor, there were no precarious moments I felt. The choreographical moments naturally provided moments of variability, but at no point did I feel that control was lost.

This means, conversely to what I had thought, that with the best orchestras and conductors, one can/must write even more extremely to fully exploit these possibilities.

In this piece though, my first intention was to exploit to the fullest the intonational capabilities of the Berlin Philharmonics.

RÉSUMÉ

Here I have discussed some premieres of recent years, and a premiere is always a very special moment because it's only then that a work truly comes to life. On the one hand, this is the greatest gift, but it's also the greatest challenge because it's the first time I am truly facing this creation and experiencing everything I was curious about, and where I have left doors open for the music to become autonomous because I have let go of control. Premieres can be easier or more difficult than expected. Often, doors open during the concerts: some things appear much richer than expected, while other details are swallowed by the overall expression. Some passages are filled with the attention of the audience, while others receive less. The most beautiful thing is when an expression emerges that I hadn't anticipated, but which may be very important for the work and opens up other perspectives. Then, this is no longer my music, but rather a music that comes to life and brings forth its own soul, and that is actually what I am seeking when I inscribe these details of uncertainty or precarity into the music: the unpredictability of a concert. And the more variables there are that can interact with each other, the more possibilities there are I think, to hear and experience a piece. This is the most important aspect for me in music I believe, as it somehow conveys that there are many different truths to one thing.