In the year of 1284, on the day of St. John and St. Paul the 26th of June, a piper dressed in colorful clothes led 130 children to the mountain of Koppenberg, where they were lost.

In the year 1284, a mysterious man appeared in Hameln. He was wearing a coat of many bright colors. For this reason, he was called the Pied Piper. He claimed to be a rat catcher, and he promised that for a certain sum he would rid the city of all the mice and rats that had infested it. The citizens struck a deal, promising to pay the price that he had demanded. The rat catcher then took a small fife from his pocket and began to blow on it. Rats and mice immediately came out from every house and gathered around him. When he thought that he had them all, he led them to the River Weser, where he pulled up his clothes and walked into the water. The animals all followed him, fell in, and drowned.

Now that the citizens had been freed of their plague, they regretted having promised so much money, and, using all kinds of excuses, they refused to pay him. Finally, he went away, bitter and angry. The piper returned on June 26, Saint John’s and Saint Paul’s Day, early in the morning at seven o’clock now dressed in a hunter’s costume, with a dreadful look on his face and wearing a strange red hat. He sounded his fife in the streets, but this time it wasn’t rats and mice that came to him, but rather children: a great number of boys and girls from their fourth year on. Among them was the mayor’s grown daughter. The swarm followed him, and he led them into a mountain, where he disappeared along with the town’s children.

In total, 130 children were lost. Two, as some say, had lagged behind and came back. One of them was blind and the other mute. The blind one was not able to point out the place, but was able to tell how they had followed the piper. The mute one was able to point out the place, although the child had heard nothing. This cave still exists today.

(Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm)

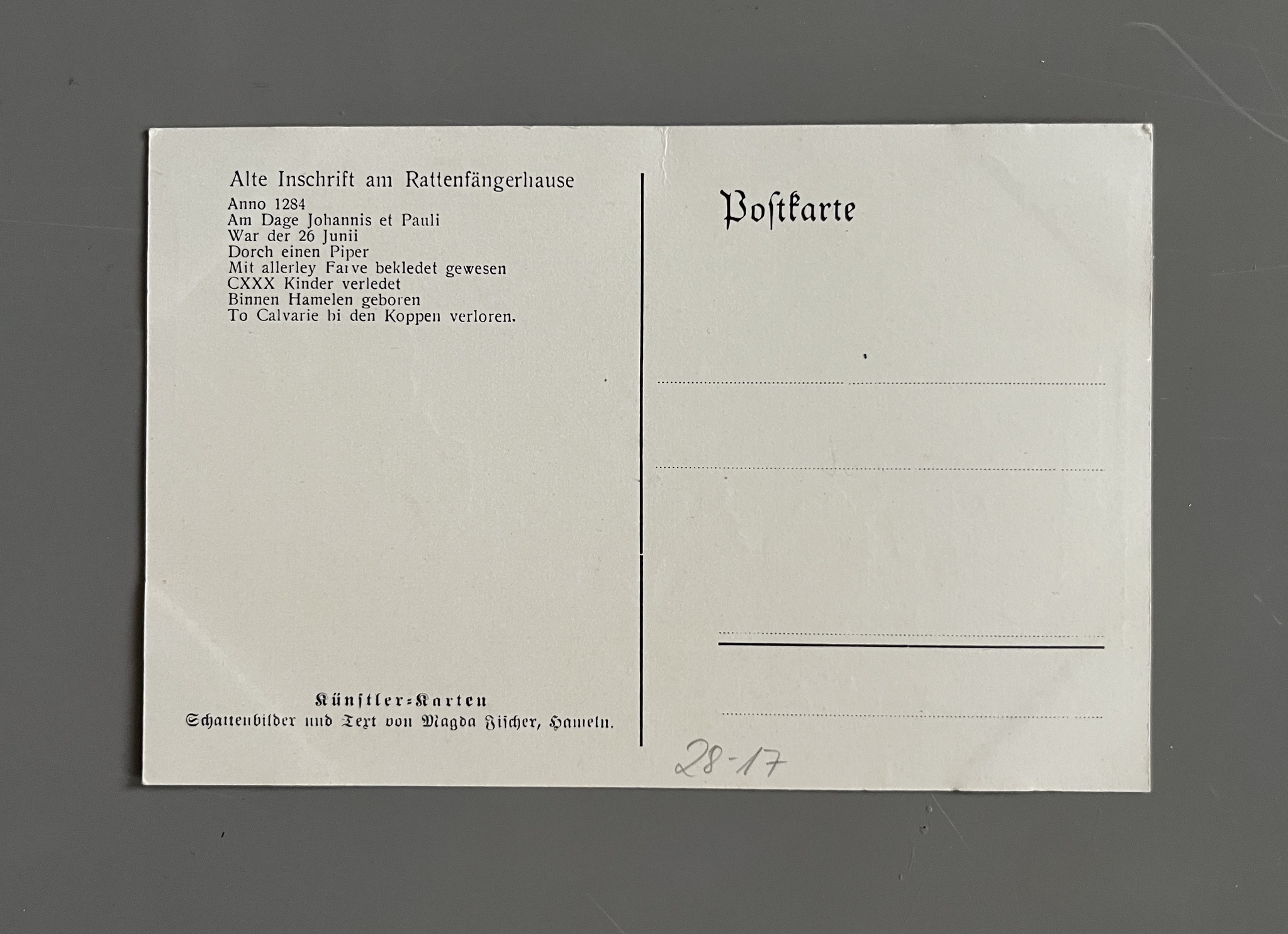

Mene-tekel. Take warning. Still today, you will find a memorial plaque on the wall of the “Rattenfängerhause” in the German city of Hameln displaying the initial text of this exposition—asking us to remember the day of St. John and St. Paul in the year 1284, when 130 children disappeared into the mountain of Koppenberg, seduced by the piper and his instrument. Writings on the wall that serve as a memento periculum instrumentalis.

The story of the Pied Piper is rich and offers several readings. Hence the story outlines various vectors to follow—some of which are mentioned below.

One vector leads us in the direction of how the city of Hameln (representing a sedimented culture) is brought to its knees by a nomadic piper (a softener of the sedimented), who takes away the future of this corrupt stagnated culture, literally, by leading the next generation, the children, into the mountain.

In relation to this, another vector aims towards how people in positions of power (historically and in present times) are linked to decisions that turn other bodies into pests; at first, the city council calls out the rats as pests that should be exterminated and makes the agreement with the piper. Later on, the city council breaks its promise, and hence the culture of the city is revealed as being rotten. The piper then decides to mirror the “solution” suggested by the city itself, this time by exterminating another kind of pest; the children of this rotten culture—pointing towards the two surviving children (the blind and the mute) as possible renewers of the culture; those being marginalized bodies within the old culture and not a part of the sedimented majority of this old culture.

“How long can a culture persist without the new? What happens if the young are no longer capable of producing surprises?”

(Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, 2009)

The idea of extermination as a “final solution” has fascist undertones and latches on to ideas of superiority and how (some) humans within a Western paradigm are often considered as being separate from (and superior to) other bodies. In this way, the story could also be read as a very relevant reminder about the entangledness of things. That we are, in fact, connected with other bodies (including the rats), and that we cannot separate ourselves from each other. Reminding us, perhaps, that we cannot “clean” our way out of our own cultural mess?

A third line of thought sees the Pied Piper as being someone who makes use of Western musical instruments in a weaponized way—a body that is capable of instrumentalizing other bodies through the use of a resonating instrumental fife body .

Memento periculum instrumentalis

Remember the dangers of instruments

Within this exposition, all of these vectors mentioned above are interwoven into a dynamic kind of tissue that is folded through time(s) in attempts to soften what has become sedimented, and thereby (perhaps) outlining more possible threads to follow.

In a Western context, agency is often delegated to human bodies when encountering other bodies (including the bodies of musical instruments), and within Western institutions, the paradigm of being a “master” of an instrument is predominant, leaving little or no agency to the instrument’s body. Within this research project, the before-mentioned dynamics are turned upside down (and inside out), turning the instrument body into a body of agency with the capacity to control other bodies including the human one.

Hence, this research seeks to excrete notions of Eurocentric universalism and firstness through a reciprocal process of othering, in which the Western instruments are approached as being estranged paranormal, parasitic, and pathological bodies.

This is not to be interpreted as if we (people of Western institutions) don’t carry a responsibility when encountering instruments, but merely as a way to designate speculative (and perhaps more tangible) bodies to what is otherwise being internalized and often camouflaged by its own oversaturation.

So, wrapped in garments of folded speculative tissue taking off from the ill tidings of the past and the “writing on the wall” warning us in the present, this project investigates Western musical instruments as being critical and even dangerous sites that should be approached with the greatest caution. Approached as liminal interfaces between the living and the dead suspended between past(s) and present(s), turning these instruments into paranormal and parasitic sites, which should be treated as such.

Instruments as pathological contaminated bodies of parasitic discourse ready to jump at you and embed themselves in you, sedimenting within you and subsequently playing you.

Instruments as haunted sites saturated with ghostlike matters of toxoplasmatic ectoplasm, fostering ghosts that will possess you. Dead and alive in the past as well as in the present, and if you are not careful, you will find yourself walking among the living dead straight into the mountain, sedimenting around you, turning soft tissue into stone.

Instruments as pathological and possessed bodies with the capacity to inflict pain on to other bodies.

Throughout history, there are more examples of instruments and instrumental bodies being capable of possessing and controlling bodies. The harps and singing of the sirens (being part bird part human), and in a Scandinavian context, the violin playing Nøkken (a shapeshifting body of horse and human) are both examples of instruments being used as ways to instrumentalize, control, and ultimately do harm to other bodies.

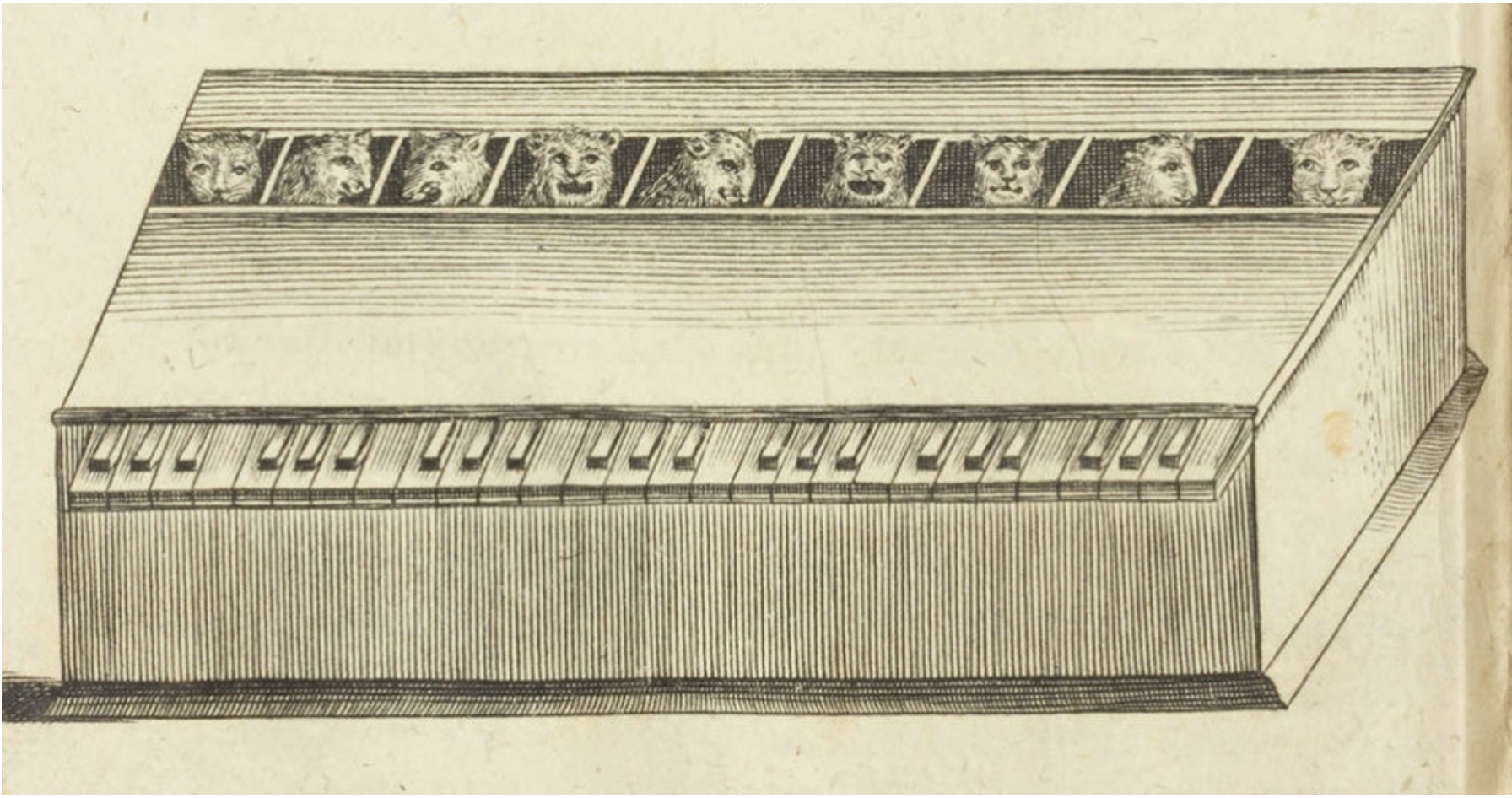

An example of the latter is the Cat Piano; an instrument suspended between fiction and reality: a Fictophone1

Within the Cat Piano, the poor cats were fixed, controlled, and tortured by a nail driven through their tails, thereby generating sounds. And using instruments to control bodies is also well known from the hunt or battlefield, where the sounds of instruments would tell bodies to retreat, advance, or to kill other bodies.

In a colonial context, we also find the sound of Western musical instruments being used as a way to control and fixate other bodies. In Dylan Robinson’s work Hungry Listening, 2020 (p.57–58), we find the following passage:

“the regimentation of activity at residential schools was instituted through the use of bells to organize daily activity. In the memory of one residential school survivor from Shingwauk residential school in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, this regimentation is re- membered as an unremitting demand that Indigenous children’s bodies conform with clock-defined time.

On weekdays, the rising bell rings at six o´clock; at six-thirty another bell calls bigger girls to help with the work in the kitchen and dining-room and the bigger boys to help with the work at the barn; at seven o´clock, the bell is rung again to call all to breakfast, and at seven-thirty prayers are conducted... At eight forty-five the warning bell for classroom work is rung, and at nine o’clock all who have not been assigned to some special duties enter their respective classrooms. Bells are rung again at recess, at noon, and at various times in the after-noon, each ring having a definite meaning, well understood by all, un-til the final bells of the day are rung for evening study, choir practice, lights out, and go-to-bed.” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015, 518–19)

Looking at a Danish colonial context, we find the following passage in Birgit Jul Fryd Johansen’s thesis from 1988 titled “Slave Schools in the Danish West Indies 1839–1853” (p. 36, source: Das Missons Blatt):

“A detailed description of how the children were taught was written by Brother Warner, 28 February 1842,77 from Friedensthal, St Croix. He described a full day at school, but unfortunately the editor only printed the first part which dealt with the arrival of the children and the Bible lesson.

Brother Warner worked at La Princess with Gardin and Gruhl in the beginning of 1840, but from May he alone was in charge of the school. There were 140 children in the beginning but as the other schools opened the number dropped to 100 (see also p. 41f). Warner described Stow’s training system by saying that it not only was supposed to give the children a certain amount of facts but should train their character by actually using what they learned. School began at 9 a.m. The playing children, some coming from quite a distance, all gathered and lined up in two rows, one for girls and one for boys, at the sound of Mr. Warner ringing the hand bell. He blew an ebony whistle to stop the talking and at a given sign the children marched in, singing a song chosen for that purpose. Girls through one door and boys through the other. Each class followed their leader (sometimes called monitor) around in the classroom, still singing and in step, and ‘in a military order they walk to their seats’ in the gallery. As the words arms and hands appeared in the song they formed their hands in praise of the Lord. At the sound of the bell, they all knelt down in prayer with folded hands and closed eyes. ‘The teacher prays slowly, and the children repeat every word after him’. At another signal from the bell, the children sat down, and the Bible lesson began.”

By Mr. Warner ringing the bell, and sounding the ebony whistle, the bodies of (140) children are instrumentalized and fixated by the sound of the instruments; “to tattoo authority on colonized bodies via the ears,” as Mark M. Smith has written written.2

The notion of sedimentation is used throughout this exposition as a vessel of both dissemination and reflection. Sometimes used as a metaphor and sometimes used in a more concrete sense, as the process in which soft matter gradually (over time) turns into hard matter.

The continuum of soft and sedimented, and how soft matter through history becomes sedimented, constitutes the overall framework of this research project. And with an interest in the notion of instrumentalization and what Western music instruments can mean, control, and do to other bodies, the instruments are approached from a (safer?) distance in the hope of emolliating the site, softening the sedimented within the instruments, softening this silent contagious and haunted body.

How to soften matter sedimented within Western musical instruments, materializing as ectoplasm through toxoplasmatic pathogens, jumping at you, engulfing you, embedding itself in your body, your spinal cord, brain and apparatus, oversaturating the horizon?

How to render visible matters of toxoplasmatic ectoplasm; this ghostlike parasitic matter of Eurocentric discourse suspended between the living and the dead? Occupying and possessing both the past and present?

“For indeed, no one has yet determined what the body can do, that is, experience has not yet taught anyone what the body can do from the laws of Nature alone, insofar as Nature is only considered to be corporeal, and what the body can do only if it is determined by the mind. For no one has yet come to know the structure of the body so accurately that he could explain all its functions – not to mention that many things are observed in the lower animals which far surpass human ingenuity, and that sleepwalkers do a great many things in their sleep which they would not dare to awake. This shows well enough that the body itself, simply from the laws of its own nature, can do many things which its mind wonders at.

Again, no one knows how, or by what means, the mind moves the body, nor how many degrees of motion it can give the body, nor with what speed it can move it. So, it follows that when men say that this or that action of the body arises from the mind, which has dominion over the body, they do not know what they are saying, and they do nothing but confess, in fine-sounding words, that they are ignorant of the true cause of that action, and that they wonder at it.”

(Benedict De Spinoza—Proposition II, part III. Of the Affects, Ethics, 1677)

What can an Instrument Do?

Before going any further, let us consider the different definitions of what an instrument can be according to wiktionary

(visited October 24th, 2023).

Please notice toxoplasmatic ectoplasma at play, sedimented within the walking-dead presumption of a female violin player and a male dentist and ditto scientist.

To the right:

Recorder encased in acrylic from the Instruments series (2020-present)

The project is divided into various parts unfolded partly as autoethnographic speculative essays, folded timelines, and artistic outcomes other than text. Via the index below, you can visit the different sites:

· inquiries into matters of toxoplasmatic ectoplasm

Since this project is derived from embodied and personal experiences of sedimentation, I feel a need to declare something about myself.

Name:

Niels Lyhne Løkkegaard (he/him)

Born:

1979, in the village of Farup, close to Ribe in the Western part of Jutland situated within the Waddensea region.

Born as the second eldest of four brothers.

My parents both worked as schoolteachers.

My mother also grew up on the west coast of Jutland, and my father grew up in the coastal city of Esbjerg (30 km from Ribe).

Since my parents weren’t allowed to play music (my mother’s family didn´t have the money, and my father’s family were against it due to religious reasons), it was paramount for my parents that my brothers and I should have the opportunity to play music.

Out of good intentions we were sent to music school—I played the reorder from the age of seven and switched to alto saxophone at the age of ten.

I don’t think I was ever really interested in those instruments, but I soon found out that when I played them on stage, I got positive feedback, which was nice. So, music for me, in the beginning, was not about the affection for an instrument (or for music for music’s sake). It was more about receiving that positive attention.

Gradually I became better at playing my instrument, and after high school, I found myself, at the age of 20, entering the RMC in Copenhagen, studying as a saxophone player.

It came easy to me, entering into a sort of robotic mode, where I would practice and practice, but I was not really reflecting on how I felt about this path of life, and hence I lived in a kind of state of numbness.

During my education, I began to write my own music, and I realized that something was “off.” It was like I couldn’t really play my own music; it was like the saxophone was playing me, rather than me playing the saxophone. At the time, I didn’t realize what was happening, but looking back now, I realize that I had reached the point of saturation and was encountering the results of sedimentation.

I graduated from the conservatory and entered a professional life as a soloist and ensemble player but was never at ease with the instrument—there was a feeling of dissonance or disconnect.

In the following years, I tried to close the gap between me and my saxophone, but it seemed impossible—each time I picked up the saxophone, it was like a saxophonistic omni-exoskeleton was playing me from both the outside and from within.

I found out that if I wanted to attain a more meaningful way of life, I would have to stop playing the saxophone.

I did so, and it allowed me to move on and take other paths, allowing me to escape the numbness.

Since then, the dynamics between saturation points, softening, and sedimentation, and how to operate within that dynamic, have been key drivers, both within my artistic and educational practices.