As set out above, I wrote two different songs from scratch over the course of 3WI. With Marie I was interested in exploring where songs come from for me: I wanted to write a song about writing a song. With Alan I was interested in writing an opener for a live set of co-written songs from my doctoral work. I call the two projects ‘Song To Be Born’ and ‘Song To Open’. These ideas for song projects arose as responses during conversation with Alan and Marie in my first maker meetings with them.

A dialogue with Marie let me put words to the experience of writing a song. She asked open questions about my sensation of song creation such as ‘where does it sit in the body?’ Songwriting for me turned out to be a very bodily experience. I felt ‘raw’ sharing the song idea, but the coaching and questions immediately produced useful insights into my process.

I recited the seven sections, then sang them while improvising some melody. We discussed the developments. The song lacked cohesion for me as well as a melody. Marie was supportive of my ideas but challenged me to go further with them, by insisting that I boil words and music down towards an essence of the experience of songwriting.

Constraints set:

- Make it yours. Use these sections, reeling off the melody, until they become more guttural. What does it feel like, getting guttural with it?

- Revisit this work (once a day or twice a week) and let the song evolve. […] Go for a walk with this sentence, until the words change into a feeling in the stomach region, the words that come from that. Distil what is there.

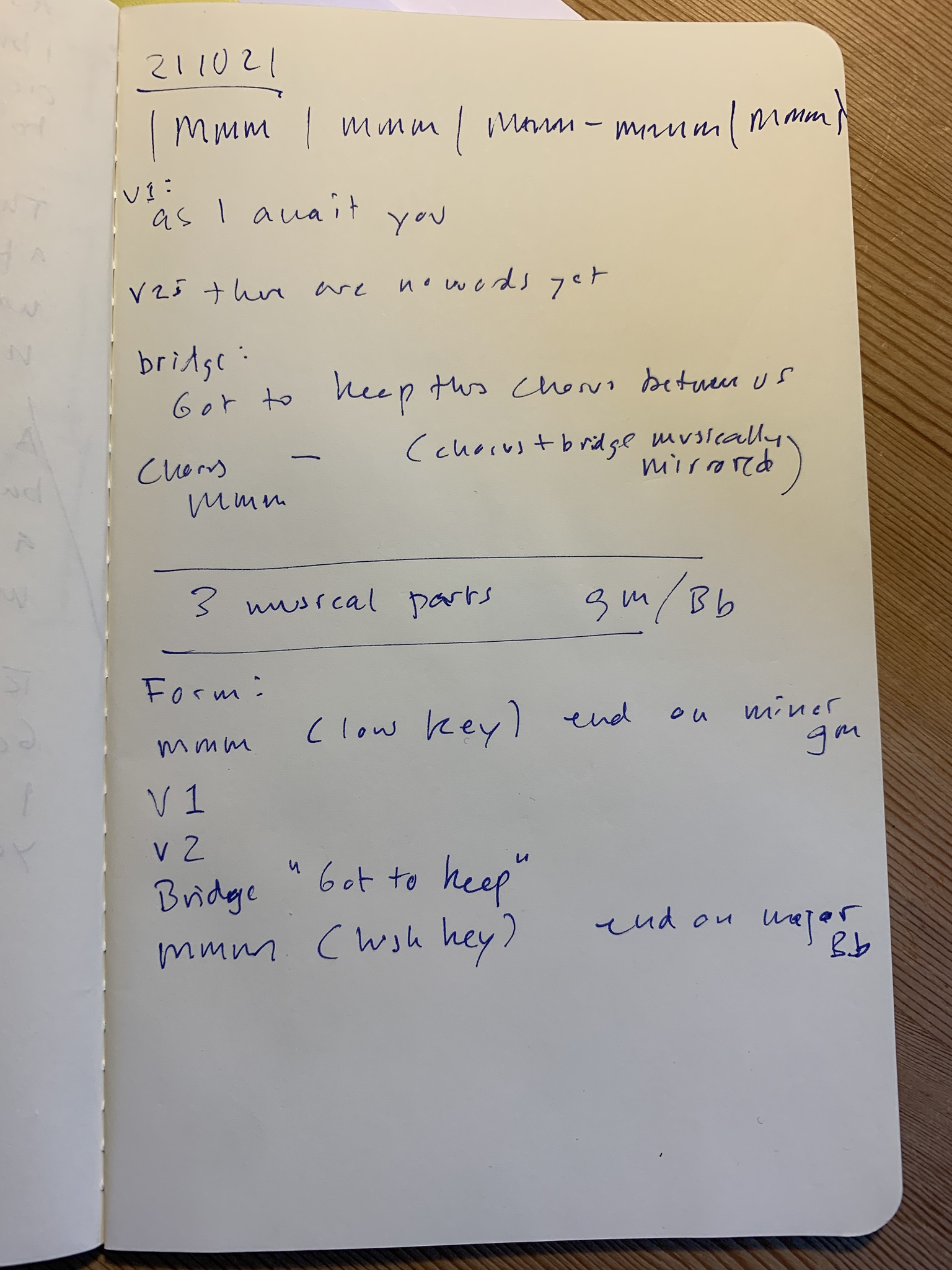

A first cyclical song section was informed by the rhythm of my walking. In a process of ‘boiling down’ the words from the seven text sections, while walking, humming, and singing, I arrived at three sections: two verses and a chorus.

Later a hummed theme was added (see video). In this way, the constraints helped to turn the source material into a song essence.

I thought the song draft was getting close to expressing my experience of making songs.

Marie said something more was needed that underscored the dramatic effect that songwriting can have on a songwriter, the physicality of singing and vocal expression working through the body, sometimes referred to as letting ‘the music play you’ (Carless 2021, 235).

Walking while singing, I moved my way vocally into a form of guttural siren, more of a primal scream than singing, which in turn became high- to low-pitched gliding ‘notes’ added to the song as a musical part in pitch with the existing sections (this new section now a musical peak that was a contrast to the existing sections). I doubled the song length, first adding different verses, but then repeating existing verses in different sequencing. This became the song I presented in our fourth maker meeting (audio clip). The constraints had been generative adding to the song form.

The evolving constraints were essential to the writing of this song. Otherwise, ineffable processes internal to the non-verbal ‘feeling ways of awareness’ of the songwriter (Blumenfeld-Jones 2016: 322), such as bodily and kinaesthetic feeling and perceptions as well as emotions, were made explicit through coaching. Walking and singing to work creatively with the source material influenced rhythm, pacing of word, and melody, and helped to structure the song. It made the process very embodied because the landscape typography and the resulting pace of the walking affected my breathing. It became a practice-phenomenological exploration of how songwriting ‘starts’ in me, and the sensuous findings are reported in the song and its emotional centre ‘I can always sing you | You always sing me’.

Coming to the session, I had the intention, as I put it in my work log, to write ‘a song that serves as an opener, a prologue, to a catalogue of co-written material with interlocutors’. Alan suggested a reference from the ‘Sirens’ episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses in which a nonsensical introduction to a chapter serves as a sort of overture. Here, motifs and little phrases were picked from the text of the subsequent chapter, and combined into fragmented writing. These elements reappear later in a context that made sense of them, but the overture treats the language not in terms of sense but in terms of musicality. The meeting was a good start, although I felt unprepared as I did not know how to fragment my existing songs.

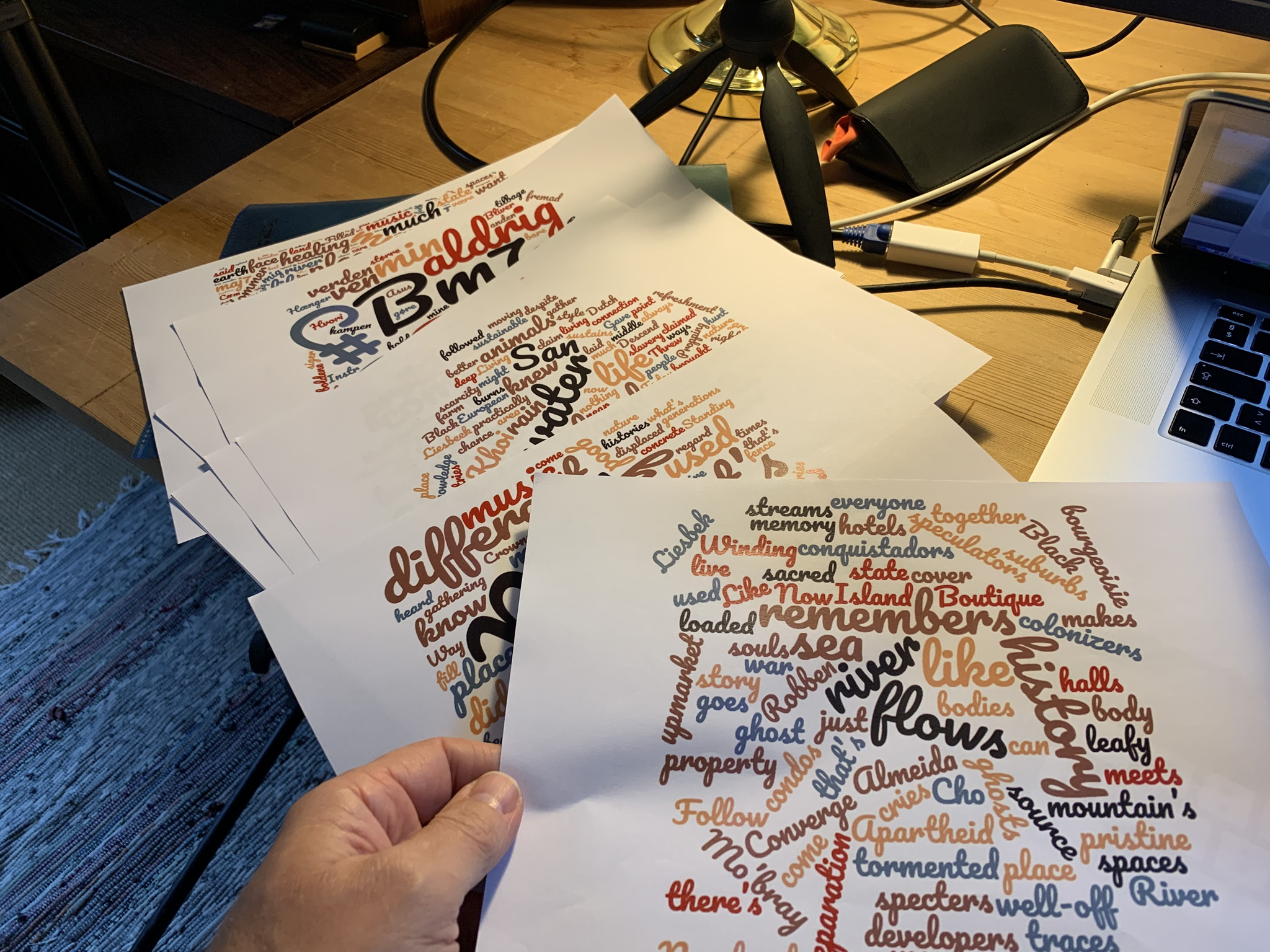

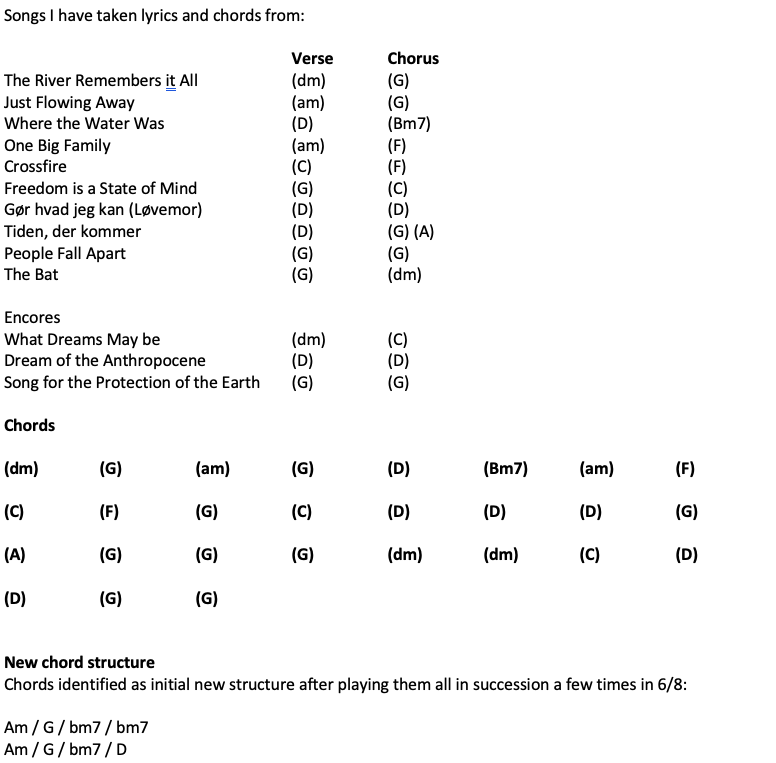

I identified a group of songs from my doctoral project I could envision performing as a live set. To break the sequencing in each song I used a word cloud generator. From separate cloud images of each lyric, I chose two to three words or expressions for each song.

To find chords for the song I took a defining chord from the verse and from the chorus of each of the existing songs, two or three chords per song. I listed them all and played them in sequence to find new chord patterns from the existing material.

These elaborate self-imposed constraints allowed ‘a way in’ (Darke 1979) to working with the constraints set by Alan.

I presented the process and outcome. Alan suggested I keep deferring sense, because the personal and co-written songs of my doctoral project involve how people feel and explore meaning-making processes through songwriting. ‘Song To Open’ would derive from this knowledge but resist organisation into linguistic sense. I had not tried to defer sense in a song before. I had troubled melodic composition in my doctoral work by using a melody game that used dice and play to find melodic strands to work with. But now I was asked to also take a ludic approach to words (to defer logical sense), and I chose to do this through the randomisation of the word cloud generator, not knowing what would come back, but that it should at least have familiar elements.

I think my sense of frustration was in part Alan’s intention in setting the constraint, as he said that I could then arrive at something ‘in a different register than the semantic sense typical of the other [PhD] material’: something that still revealed something about the songwriting practice, because it could communicate in sung form even if in a fragmented or nonsensical way. In the audio clip from the meeting, I explain how my approach to Alan’s attempts to frustrate the ‘sincerity’ in my writing practice led to my applying further constraints, even if, for Alan, sincerity reasserted itself.

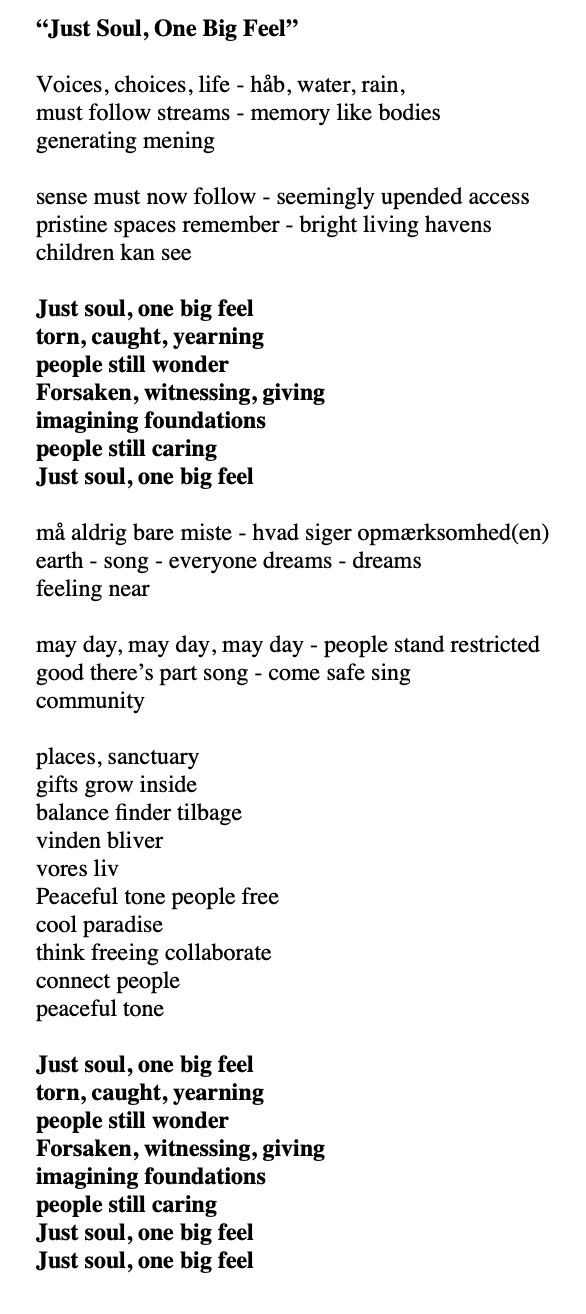

Because sense in ‘Song To Open’ was fleeting, it was difficult for me to feel or find the song’s emotional centre. I would force this process for maker meeting four by re-fragmenting/rewriting the draft. I put the existing fragmented lines together in verse and chorus units, paying attention to emotion but still deferring linguistic sense. I used one fragmented phrase, ‘just soul, one big feel’, as a chorus hook line to express the song’s emotional centre as well as commenting on the inherent sincerity in the songwriting of the source material. The co-written songs in the doctoral project were about different lived experiences, and I wanted this to be expressed in a way that I could feel — making musical and sensuous, if not literal, sense.

I ended up with a singable song (video clip), although one that was hard to memorise, as there was no logical progression in the lyric to the song. The process taught me that I gravitate towards songwriting as a meaning-making process, not a process that defers (literal) sense.

This is reflected when I play the song now, several months on. The song does not allow me to revisit a certain feeling or sentiment I was dealing with in the songwriting moment. While it successfully defers logical sense, it also defers a sense of gratification that I as a singer and songwriter am used to navigating towards, and which also helps me curate which songs will make it into a live set or onto an album.

However, the continuous addition of decisive constraints to defer the meaning-making elements of my confessional songwriting practice generated a materially new way of working (e.g. by incorporating a word cloud generator). This was interesting, and it could prove useful in future songwriting projects.