Introduction

Anthony Braxton coined the term Creative Orchestra in the early 1970s to describe a specific subset of his “Large Ensemble Musics.” In contrast to his fully notated works for orchestra (or multiple orchestras), his compositions for the Creative Orchestra are characterized by a combination of traditional notation and various degrees of open material and improvisation within an orchestral context. Braxton’s distinction has always been somewhat ambiguous. From the moment he introduced his holistic Tri-Centric Model in the late 1980s, where any composition can be combined, superimposed, or integrated into any other part or composition from his catalog of works, one can say that all of his Large Ensemble Musics can potentially carry the Creative Orchestra label.1

In addition to this musical distinction, Braxton’s term for the Creative Orchestra also carries an important social dimension. In a recent article, I took a closer look at the history of Braxton’s Creative Orchestra concept with a specific focus on the social context in which these works were created.2 I described how Braxton’s term for the Creative Orchestra is historically directly connected to the AACM’s use of the term Creative Music.3 Braxton uses the term as and alternative to “jazz-orchestra” or “swing band” in order to place his work outside the persistent jazz/classical binarity, creating a new historical narrative or framework that is necessary to understand his work on its own terms. I concluded that these social aspects are not separate from the work itself and that looking at Braxton’s Creative Orchestra Music as part of an intricate ‘assemblage’ or constellation of social mediations rather than a historically delineated musical tradition, offers an entirely new perspective on what orchestral practice can be.4

However, to implement such a new narrative, it also takes orchestras to perform these works, and until today, very few classical institutions have programmed Braxton’s orchestral works. Through my research, I was fortunate to have three occasions to perform some of these compositions in three distinctly different institutional contexts. I conducted a student ensemble at the conservatory in Antwerp, I gave a workshop together with Braxton as part of the Darmstadt International Summer Course, and, lastly, together with Ilan Volkov, I co-conducted two performances with the Brussels Philharmonic and the Ictus ensemble. This gave me valuable insights and allowed me to better understand the implications of this repertoire. In what follows, I will give a detailed description of these first-hand experiences, how to approach this radical repertoire, and what the potential obstacles are.

1. Royal Conservatoire Antwerp

My first experience working on Anthony Braxton’s Creative Orchestra repertoire was in 2021-22 when I had the opportunity to work with a student ensemble from the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp (RCA). The goal was to perform a set as part of a larger event at De Singel International Arts Center in Antwerp on June 5th, 2022, celebrating the music of Anthony Braxton, which I helped curate.5 The Creative Orchestra set was the first part of a three-part concert that also included a set of Ghost Trance Music and ended with Braxton himself playing with his saxophone quartet.

For this project, I made a selection of compositions from the Creative Orchestra Music 1976 album, more specifically Compositions No. 56, No. 58, and No. 59. I knew these pieces well from the available recordings,6 and the scores were readily available from Braxton’s Tri-Centric Foundation. The project was intended for graduate-level students. Each year they have the option to participate in several projects for which they receive course credits; the Braxton-Creative Orchestra was one of those projects. Even though I didn’t communicate it as a jazz project, it wasn't very surprising that the interest to participate was strongest within the jazz department. Nevertheless, I insisted on having students from both jazz and classical departments. With the persistent jazz/classical binarity being very strongly embedded in the educational institution of a conservatory, I thought it would be difficult to do so, but having the prospect of a concert at a high-level venue in the presence of the composer was a good incentive for both school departments to present this project for their students to participate in.

The eventual ensemble consisted of 21 musicians, with twelve students from the jazz department and nine from the classical department.7 For the choice of instruments, I stayed close to the instrumentation of the specific compositions, which in the case of No. 56, No. 58, and No. 59 for a large part still reflects that of a big band: heavy in winds and brass and no strings. I accepted a few instruments that weren’t in the scores (electric guitar and bass), and even though not all instruments had parts in every composition, I made sure everyone got a part to play in each piece, sometimes doubling another part or filling in for one that was missing, so, for example, the guitar and bass would play trumpet 4 and trombone 3 in No. 59 because I only had 3 trumpets and 2 trombones in the orchestra. In addition to the dress rehearsal and concert in June, there were two rehearsal periods with three-hour sessions spread over 5 days each. The first rehearsal period took place in November 2021, the second in February 2022. Apart from this being my first experience conducting Braxton’s orchestra repertoire, it was also the first time I conducted a large group of musicians. Not knowing what to expect, I was happy to have a decent amount of rehearsal time spread out over the year.

Since all the students were at a graduate level, reading through the different compositions went fairly easy. From the three compositions I selected, No. 58 was the most difficult to put together with its seemingly straightforward marching melody that gradually, but very precisely, deconstructs into sections of solo-improvisations. During the rehearsals, I also decided to add Composition No. 69Q from his quartet book, a piece I had been playing with my own chamber group, and which turned out to work quite well in an orchestral setting too.

Aside from the scores, moments of collective and individual improvisation are a crucial aspect of Braxton’s Creative Orchestra compositions. Improvisation is integrated into the scores, but in addition to that, at any given moment during a performance, one can always use Braxton's system of Language Music (LM) to improvise outside the score as well.8 Braxton developed a system of cues using a list of twelve so-called “Language Types” to guide collective improvisation. During the rehearsals, I explored different ways of using these cues to guide the orchestra through LM improvisation, also allowing for multi-hierarchical strategies to arise. I ended up applying the following three LM strategies:

-

The conductor cues any of the twelve Language Types, receiving immediate responses from the orchestra as a whole or indicated subgroups (left or right side of the orchestra, only brass, piano-solo, etc.).

-

The orchestra members chose their Language Type, when the conductor cues a number they had chosen, this meant they could play. This situation created unforeseen combinations, ad hoc subgroups, and even solos to emerge, which were not controlled by the conductor.

-

The orchestra is divided into four subgroups, each with a section leader. The section leaders are free to cue any of the Language Types. In this version, the orchestra becomes independent and doesn’t need a conductor anymore.

I was aware of Braxton's holistic Tri-Centric philosophy, where he encourages musicians to try and connect the different compositions. I decided to apply what Braxton calls "coordinate music" for our eventual performance. This is a process where the different compositions are performed separately but connected through improvisation into a continuous suite, using LM to ‘glue’ the pieces together.9 So in practice, when we played the compositions, my role was that of a traditional conductor, keeping time. But, instead of ending each composition, we transitioned from one composition to the next through collective improvisations using the Language Music system.

Performance analysis10

The performance on June 5th, 2022 started with a short section of LM (1st procedure) and then at 02’39’’, went into No. 59. This lasted for about 6 minutes, after which we went back to a longer stretch of LM, this time exploring the 2nd procedure. At 12’21’’, we jumped into No. 69Q, which only lasted for a little more than two minutes and was immediately followed by another stretch of LM. This time we applied the 3rd procedure where I briefly left the stage, and the section leaders in the orchestra took over the role of cueing. This took us past the first half of the performance as I returned to the stage and brought the orchestra into the slow-paced sonic textures of No. 56 at 16’38’’. At 21’20’’, we went back to the last stretch of LM (1st procedure) where I guided the orchestra to the grand finale of the set at 25’15’’ with the exciting march of No. 58, which lasted about 8’. The last note of No. 58 also marked the end of the performance.

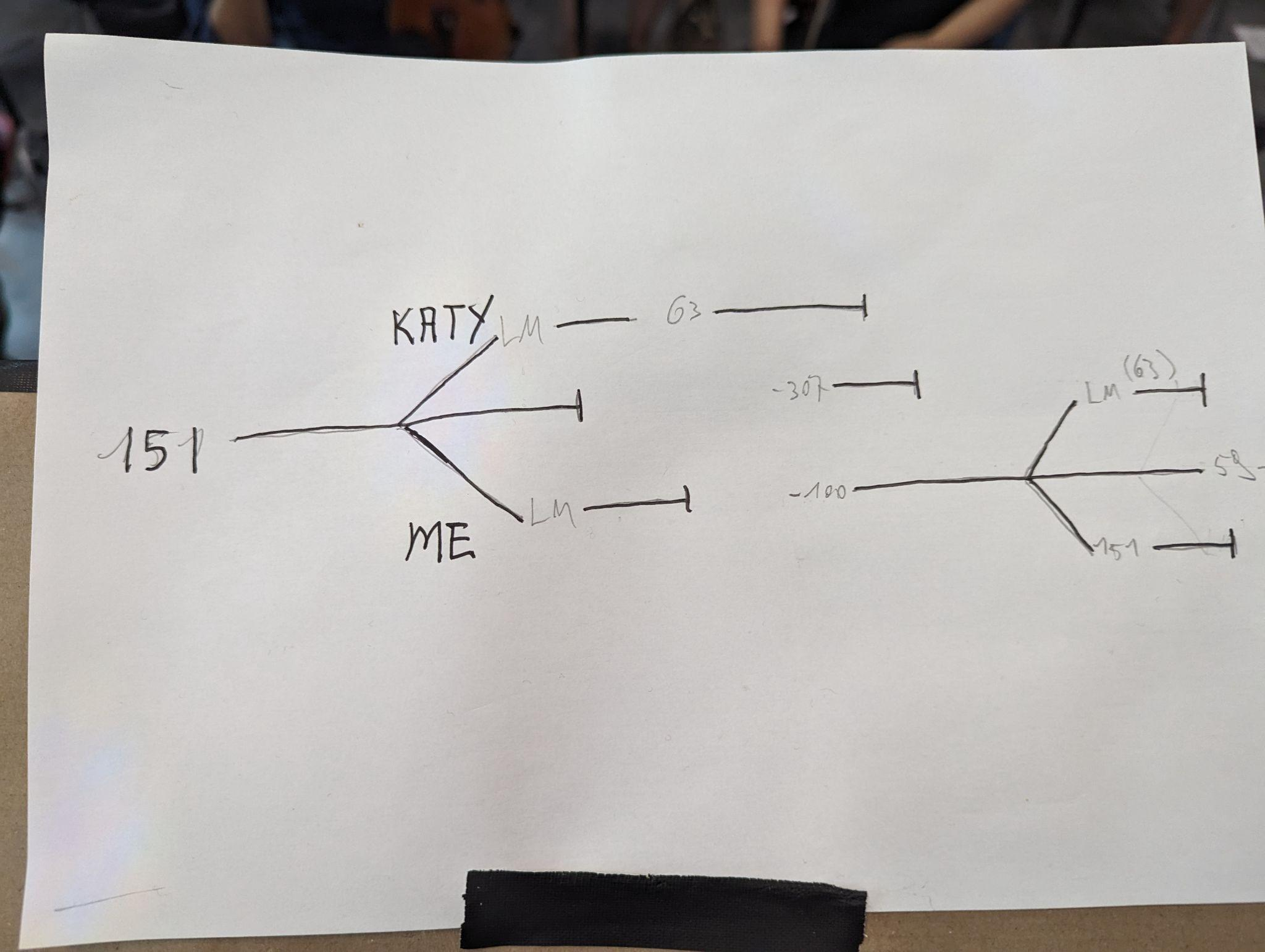

In Braxton’s Tri-Centric Model, his compositions, or "stable logics," are represented by a square, while improvisation, or "mutable logics," is represented by a circle. Any given performance of Braxton’s music also implies a third element, "synthesis logics," represented by a triangle, which results from the combination of both stable and mutable logics and is linked to intuition and the unknown. Braxton often refers to imaginary places and maps when speaking of his music, where the musicians have to ‘navigate’ through it. Using this image of a map as well as Braxton’s Tri-Centric symbols of square-circle-triangle, a visual representation of the RCA-performance could be presented as in fig. b (on the left).

Afterthoughts

Working with the students was an overall very positive experience. None of them (whether jazz or classical) had any previous experience with Braxton’s repertoire, and there was some hesitation towards the experimental aspects of the music. It was clear that the jazz musicians were more at ease with improvisation, but the unusual combination of very precise scores and improvisation pushed all the musicians out of their comfort zone. I decided to spend at least as much time on LM improvisations as on rehearsing the specific scores. Since the instrumentation was heavy in winds and brass, any form of free improvisation has a tendency to become very loud very quickly, so we had to explore different strategies for breaking down the massive sound of the group as a whole, working with dynamics, using space and silence to have individuals or subgroups emerge, etc. None of these strategies are explicitly described within Braxton’s LM system, but they are inherently a part of it and can be explored in many different ways.

In the end, the students were clearly unified in this Creative Orchestra, effectively turning the traditional separation between the jazz and classical departments of the conservatory obsolete. This experience convinced me that allowing for a diversity of practices within the conservatory walls can lead to interesting new pedagogical approaches to music making, from solo to large groups and orchestras.

2. Darmstadt International Summer Course

In August 2023, Anthony Braxton was invited as one of the central guests of the International Summer Course for New Music in Darmstadt, Germany. This bi-annual festival has been historically very influential for the development of post-war Western art music and still today is considered one of the most important gatherings of the international new music community. Anthony Braxton’s extensive body of work has existed largely outside the official discourse and historical canon of Western Art Music. His presence at the Darmstadt Summer Course was an important statement to give his life’s work the attention it deserves. Several performances around his work were planned, as well as a two-day international conference which I co-curated with Prof. Timo Hoyer.11 After my experience performing Creative Orchestra music with the students of the RCA, I suggested to festival director Thomas Schaeffer the idea of organizing a workshop around Braxton’s Creative Orchestra for participants of the Summer Course. He gladly accepted, and in turn, suggested I would co-lead the workshop together with Braxton himself. We decided on a four-day workshop with 3-hour sessions on each day from August 11 to 14, followed by a public performance on August 15.

The workshop was open to all participants of the summer course who could apply through a call published by the festival. There was a total of 33 participants, coming from different parts of the world and mostly with backgrounds in classical/contemporary music (click the program booklet on the for more details).The instrumentation was left open, and as there was a significant string and wind section, the overall instrumentation of this Creative Orchestra came much closer to a classical orchestra than a big band. Carl Testa from the Tri-Centric Foundation had provided me with several possible compositions to use for the workshop. I made a selection of scores and, when in Darmstadt, I sat down with Braxton to decide which pieces to use for the workshop. I suggested Composition No. 151, an extensive piece for a creative orchestra of 25 players, as our central composition or “primary territory” for the workshop.12 I also selected Composition No. 63 (for two soloists and chamber orchestra) and the compositions I had done previously with RCA (Compositions No. 56, No. 58, and No. 59). Braxton accepted my suggestion of Composition No. 151 and Composition No. 63. He then added Composition No. 100 (for 15 instrumentalists) and kept Composition No. 59.13 Since there was a vocalist in the orchestra, I also added the solo-voice line of Composition No. 307 (for soprano and orchestra).14

We started each session with Language Music. Braxton initiated the first rehearsal without explaining much about the system; he immediately had the orchestra play and improvise collectively. Although confusing at first, as most of the musicians were figuring out the different cues and signs on the go, Braxton’s presence and conducting immediately generated a creative and energetic response from the musicians. He then provided more indications about the different signs and mostly gave comments on volume and balance. As a general guideline, Braxton instructed everyone to maintain mezzo piano as the default dynamic. We didn’t work extensively on different strategies of using the LM system as I did with the students in Antwerp.15 Braxton trusted the musicians to bring in their own interpretations and creative responses to his cueing.

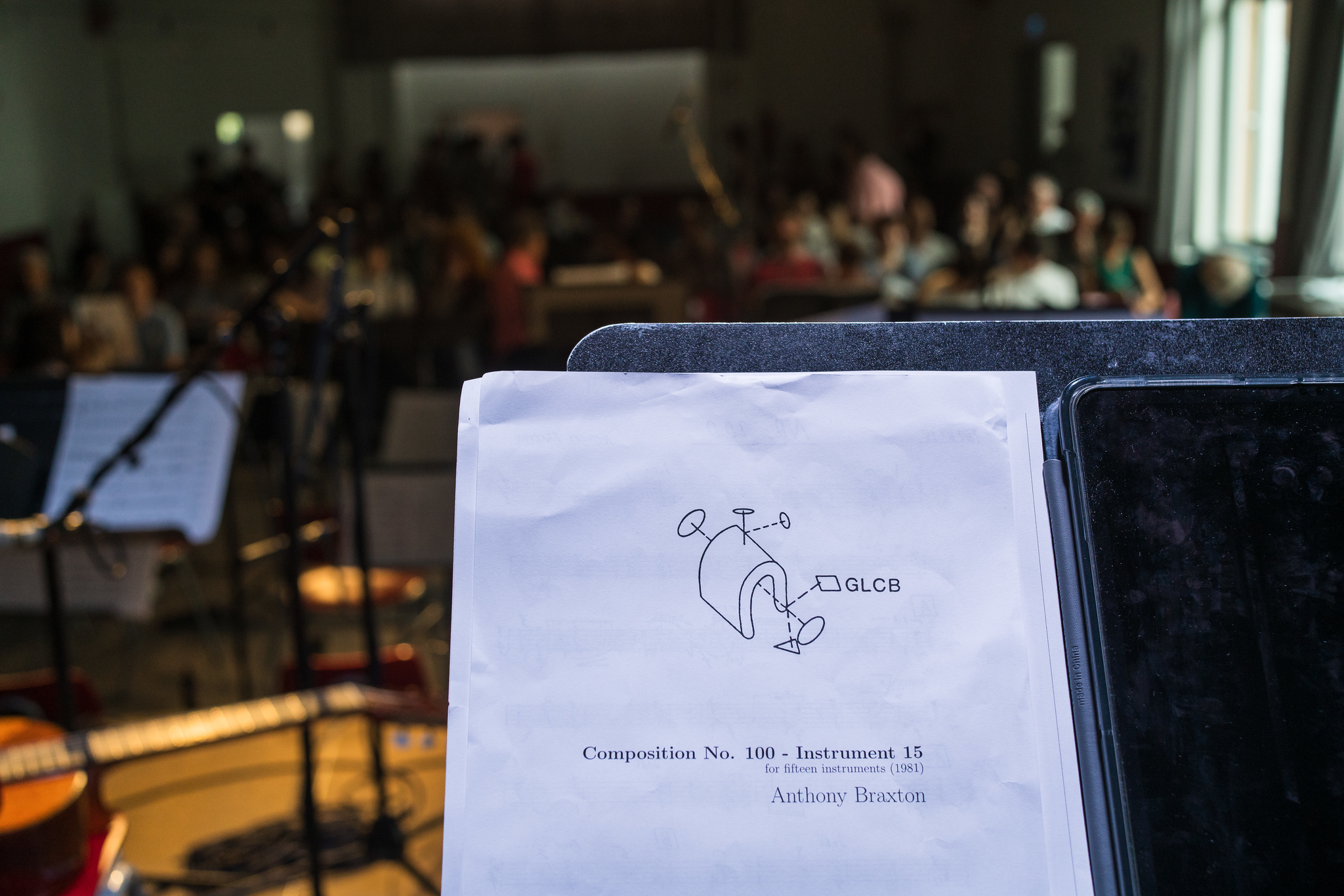

Following these LM sessions, we then started working on the different compositions. The musicians had access to parts for all of the compositions we selected, so they were engaged at all times to participate.16 We rehearsed each piece separately; I conducted Composition No. 151 and Composition No. 63, while Braxton worked on Compositions No. 100 and No. 59. It was a lot of music to go through, so we mainly read through the compositions so that the musicians could become familiar with the material. The notation in some of the pieces is very complex, especially in Compositions No. 151 and No. 100, where many graphic shapes and symbols indicating different kinds of improvisation are integrated into the otherwise conventionally notated parts. During these rehearsals, Braxton was very precise, especially in terms of time and rhythm, often counting out the beats aloud.

For the eventual performance, I suggested the idea of combining the different compositions, following Braxton’s holistic Tri-Centric model. This time, not by moving from one composition to the next in a linear way (as I did with the students in Antwerp) but by allowing different compositions to happen simultaneously. In order to do this in an orchestral context, Braxton developed a multi-hierarchical system of three conductors to lead the ensemble simultaneously. In this Tri-Centric performance, as Braxton calls it, the musicians of the orchestra have to decide individually which conductor to follow. Braxton was excited to try this out in the workshop, and so, on the fourth and last workshop session, we invited composer Katherine Young, a former student of Braxton and herself one of the tutors at the summer school, to join as the third conductor.

Braxton and I agreed on a general performance plan. I would start the orchestra with Composition No. 151 and at some points cue in the singer with Composition No. 307; then Braxton joined in with Compositions No. 100 and No. 59, and Young with Composition No. 63. Other than this general timeline and the assigned compositions, nothing was set in advance. All three conductors could alternate between conducting the compositions and giving LM cues for improvisation. We used whiteboards to give rehearsal marks to clearly indicate where to start when one of us picked up a composition. Whenever we gave a hand cue of a “circle,” it meant we would go into LM. We would also, at points, stop conducting to leave space for the other conductors/compositions to emerge. The musicians were at all times free to choose which conductor to follow.17

Navigating between complex scores, improvisational cues, and multiple conductors presented quite a challenge for the performers in the orchestra. Instead of spending more time having the musicians get used to this process or trying to fix certain combinations of pieces so the musicians could anticipate what would happen in the performance the next day, Braxton cut the last and only rehearsal with the three conductors short, with the words: “This will be interesting tomorrow because I want that unknown, known, and intuition… The intuition should be jumping all over the place!” In other words, he wanted to keep the energy fresh and have the musicians navigate the material in real-time during the performance, a central element in the performance practice of Braxton’s music.18 Braxton puts a great deal of trust in the performers, allowing their individual agency to play a defining role in the eventual progression of the music. He famously stated that you can’t make mistakes in his music,19 but being part of his Creative Orchestra, in return, means having the discipline to accept unknown situations and outcomes and ensuring that trust is mutual. This was very much the case in Darmstadt, where all the participants in the Creative Orchestra were fully engaged. Even though there was confusion at many moments in the rehearsal process, at the same time there was a clear mutual understanding of Braxton’s intentions and a strong willingness to accept this radical openness.

Performance Analysis20

The eventual performance lasted a little over 30 minutes. Apart from the beginning, we quickly drifted away from the general performance plan we had made, with all three conductors and the orchestra musicians navigating their way through the material. Listening back to the recording, it is amazing how the written material and the improvisations (the stable and mutable logics) completely blend together in unforeseen ways (synthesis logics). The performance started with an improvisation, which is actually the beginning of No. 151,21 continuing until approximately 3’45” when Braxton started conducting No. 100. The clear rhythmic/repetitive cells of No. 151 can be recognized when it resurfaces at around 11’28’’ for two minutes or so, and again between 21’52’’ until around 25’. Another recognizable part is the vocal line from No. 307, which appeared first on 07’49’’ and re-emerged throughout the performance. A beautiful moment occurred at 16’45’’ where the voice of No. 307 collided with tonal chords in the strings, most likely rehearsal mark D3 of No. 63, here conducted by Katherine Young. At around 25’16’’, we hear Braxton conducting the recognizable staccato attacks of section B of No. 59 with the guitars acting as soloists. In several sections of the performance, LM types can be recognized. It is impossible here to retrace the exact development from beginning to end, but an overall "Tri-Centric" visualization of the performance would look like fig. d (on the left).

Afterthoughts and testimonials

Working closely with Braxton, watching him rehearse and conduct his own pieces, was a unique opportunity and left a big impression on everyone involved. Braxton’s multi-hierarchical approach to the orchestra, combining improvisation with highly complex scores, and at the same time nurturing a general feeling of trust and self-realization for each individual musician, posed a convincing alternative to the generally accepted notion that a strict, central hierarchy and supervision is the only way to organize larger groups of musicians (or people in general). Violinist and conductor Sinead Hayes, one of the participants in the ‘Words on Music’ workshop of the Summer Course, followed the workshop closely and made an audio-documentary about it, including testimonials from some of the participants as well as from notable audience members and interviews with Braxton himself. Sinead Hayes' podcast can be listened to in its entirety here. I highlighted some of the testimonials below:

Elizabeth Garthman (soprano, US): Rhythm is what we’re aiming for the most. (...) It’s not just chaos, when there are many moments that line up, rhythmically and dynamically, that’s really special. (...) Working with him, being in his presence, it honestly allowed me to find a new joy in singing.

Pablo Jimenez (double bass, Columbia): Fantastic, really really fantastic. On a personal level listening to his music has been incredibly enriching and eye-opening on the different ways that you can make music. Being able to work with him directly is huge.

Tadashi Lewis (clarinet, US): It was cool, it was a lot of stuff but not too overwhelming, it all worked out.

Maria Morfeo (voice, Mexico): It was fantastic, it was really intense. It requires a lot of your attention and your mindfulness.

Émilie Fortin (trumpet, Canada): It was amazing, it went by so fast and it’s the kind of thing you could play for hours.

Kalun Leung (trombone, China): It was very inspiring, and it’s going to inspire me for many years.

Tyshawn Sorey (composer, US): One of the most beautiful things with Anthony’s music, and working in this situation with the creative orchestra, is that all of these compositions, no matter how familiar you are with them, they are going to sound different every time. Not only is that a byproduct of generational relation with the materials that Braxton presents, because a lot of this music has been around for 3 or 4 decades, so with every player the interpretation is going to change, but when you put it into the context of Creative Orchestra Music, the whole dynamic of how the composition works is completely altered in so many beautiful ways and to see this happen with 3 conductors was a very pleasant surprise.

Alvin Singleton (composer, US): This orchestra (...) has got such a great variety of instruments, variety of ages and variety of colours. I’m just hoping they remember this experience and they repeat it wherever they live.

George E. Lewis (composer US): The Darmstadt Ferienkurse has been an amazing experience, but none better than this, because I heard pieces I performed with Anthony in the mid ‘70’s, performed here by Tadashi Lewis, my wonderful son on clarinet.

3. Ictus, Brussels Philharmonic & Ilan Volkov

The Ictus Ensemble, a Brussels-based group specializing in contemporary music, had been following my research on Braxton for several years.22 When they were looking into including a Braxton composition in a new concert program in collaboration with the Brussels Philharmonic Orchestra, I suggested to them his repertoire for Creative Orchestra. This eventually led to a concert program entitled Forces In Motion, which was presented at two occasions at the Concertgebouw in Bruges and DE SINGEL International Arts Center in Antwerp on November 16 and 17, 2023.23 Part of the artistic coordination for this performance landed on my shoulders, and I was fortunate to be able to meet with the conductor for this project, Ilan Volkov, while in Darmstadt. Having had direct experience working with Braxton in Darmstadt, I suggested to Volkov to do a similar “Tri-Centric performance” with the Brussels Philharmonic and Ictus. There have been a handful of previous performances by classical orchestras of Braxton’s work (Volkov had conducted Compositions No. 27 and No. 63 before with the Glasgow Symphony Orchestra), but always in their "origin state" from beginning to end. However, a “Tri-Centric performance” with several pieces combined, using Language Music improvisations and the multi-hierarchical situation of three conductors, had never been done before by a traditional orchestra. So this would be a historic event. Volkov immediately accepted and trusted me with providing the necessary scores and instructions.

I proposed Composition No. 151 again as our "primary territory," as well as sections from Composition No. 63. This time, I also added parts from Composition No. 147 (When Chancey Speaks, The Number 3 Changes Lights) for 16 instrumentalists and 3 soloists. For this performance, the orchestra consisted of 25 musicians (in accordance with the parts of Composition No. 151), 19 of whom were musicians from the Brussels Philharmonic and 6 (including me) from the Ictus Ensemble. Volkov was the chief conductor, I played guitar in the orchestra and functioned as the second conductor to conduct Composition No. 147, and as the third conductor, we had the concertmaster of the orchestra, Henry Raudales, to conduct parts of Composition No. 63. In addition to this, the Ictus musicians had a more autonomous role in the orchestra, like an ensemble within the ensemble. We kept some of Braxton’s smaller compositions from the quartet books (Compositions No. 6F, No. 40F, and No. 69Q), which we had played in previous performances of Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music. Within the context of the Creative Orchestra, I could cue in these pieces at any moment separately from the rest of the orchestra. As one of the Ictus musicians was a singer, soprano Maris Pajuste, I also gave her the solo vocal line from Composition No. 307, which I would cue, or she could insert at any given moment in the performance.

There were three rehearsals of one hour and a half. I started the first rehearsal with a quick introduction to LM. We then rehearsed the different compositions separately, but quite early on started collaging the different pieces together, adding LM and exploring the multiple conductor situation. Moving away from the score and making their own musical choices was perhaps the most difficult for the musicians of the orchestra, so we spent a good deal of rehearsal time on improvisation, not only in terms of dynamics and balance but also on creating sharp and spontaneous responses to sudden graphic shapes in the score or LM cues. In comparison to the Darmstadt performance, we decided a few more things in advance for our concerts in Bruges and Antwerp. Since it was part of a larger concert program, we had to keep to a maximum duration of 30 minutes. Volkov and I used a chronometer to keep track of time. I made an overall performance structure with Volkov starting with Composition No. 151. I started conducting Composition No. 147 at around ⅓’rd of the performance, and Raudales came in at ⅔’s with Composition No. 63. In between these moments, I also inserted the additional Ictus pieces, the order of which was left open. Volkov and I would at times stop conducting and move to LM and then pick up a different page, sometimes going back or moving several pages forward. The 3rd conductor Raudales stuck to conducting Composition No. 63 and didn’t add any LM. The conductors used whiteboards to clearly mark where in the score they started conducting.

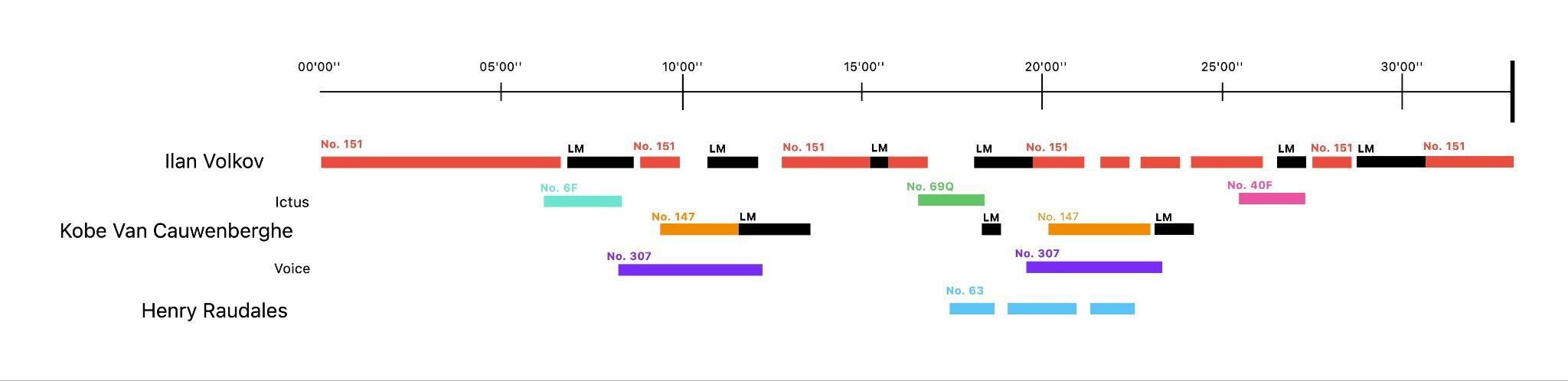

Performance Analysis24

The performance in Bruges was filmed, and based on the footage, I made a detailed analysis of the full performance (see fig. d). For the first six minutes of the performance, Volkov conducted No. 151. I then cued in the Ictus players to start No. 6F. Shortly after that, Volkov switched to LM with the rest of the orchestra. When No. 6F wound down at around 08’15’’, the solo voice part from No. 307 emerged, and Volkov brought part of the orchestra back into No. 151. At 09’30’’, I started conducting No. 147; Volkov paused No. 151 while the vocal line continued for a few minutes more. Just before 11’, Volkov started giving LM cues again. Shortly after this, I moved from No. 147 into LM as well. After a brief pause, Volkov picked up No. 151, bringing back the full orchestra as soon as I stopped cueing LM. Apart from a brief LM interruption, the orchestra remained in No. 151 with Volkov until I brought in Ictus again at 16’45’’ with No. 69Q. Volkov paused as we moved into the densest part of the performance when, at 17’35’’, the 3rd conductor Raudales started conducting No. 63, which he continued with two brief pauses until 22’33’’. While Raudales conducted, the Ictus musicians moved from No. 69Q into LM, and Volkov also started giving LM cues. The singer picked up the vocal line from No. 307 again, and at the same time, Volkov started conducting No. 151, while I brought in No. 147. From here on, Volkov mostly stayed with No. 151, but with short breaks to leave space for the other material to emerge. The density reduced when I ended No. 147 shortly after Raudales stopped No. 63, but I then continued briefly with LM. I brought in the Ictus musicians one last time, now with No. 40F, a little after 25’ while Volkov went back to LM. For the last five minutes of the performance, the full orchestra returned to Volkov, who alternated No. 151 with a brief LM section and finally ended the performance in No. 151.

When comparing the (audio-only) recording from Antwerp to the version from Bruges, performed one day earlier, it clearly shows how vastly different both performances were in terms of their development because of the multi-layered and multi-hierarchical possibilities of Braxton’s music and the many choices that are made on the spot by the conductors and the individual players. Feedback from musicians and audience members who attended both performances often favored the performance in Bruges, citing its heightened energy and musical intensity. This is maybe due to the fact that it was the first performance, and everybody was a bit more ‘on edge’. The difference in acoustics between both venues also might have played a role in how it was perceived. I personally experienced the second performance as having more musical depth, I felt the orchestra was listening more attentively while navigating the material, which made it texturally richer. We kept the same compositions and overall structure for both performances, so even though in a linear representation the blocks would likely shift around quite a bit, a general "Tri-Centric map" of both performances still looks the same (see fig. e).

Afterthoughts - Working with the orchestra

The preparation for this performance was again very different from the previous ones. For the performance with students in Antwerp, I had a lot of rehearsal time, and I kept the repertoire relatively simple so we could really dig in and explore the material in a fairly straightforward way. In Darmstadt, the participants of the summer course came from different corners of the world specifically to learn New Music, new scores, and to experiment. They were very eager to absorb Braxton's experimental approach to orchestral performance practice, and having his presence there obviously also created a special kind of energy around his work. With the Brussels Philharmonic, I entered the institutional world of the classical orchestra, which created its own set of challenges.

Many questions arose around the scores that needed answers right away. Braxton’s (orchestral) scores are, to a large extent, traditionally notated, but there’s a lot of space for open interpretation in sections where he uses graphic notation and all kinds of geometric shapes. Braxton rarely gives clear instructions as to how to interpret these; he expects an intuitive approach to his extended notation which needs to be dealt with during the rehearsals. For Ilan Volkov, this was quite clear, as we kept in touch via email after our meeting in Darmstadt and had a video call the week before the first rehearsal. I also met with the Ictus musicians separately to make sure they had all the necessary information. However, it was much harder to know in advance how the orchestra musicians would respond to Braxton’s scores and to the fact that they were required to improvise as well. It occurred to me that the traditional hierarchy of a classical orchestra is not easily bypassed. The institutional machine of the orchestra meant that I was never in touch with the orchestra musicians directly before the first rehearsal but always through the orchestra office, to whom I relayed as much of the relevant information as I could. Another interesting situation arose when the orchestra was asked to provide a third conductor for the performance. Following the orchestral hierarchy, it was necessary for them to ask their concertmaster first, even though in Braxton’s multi-hierarchical approach that could have been anyone from the orchestra. Chief conductor Ilan Volkov understood Braxton’s multi-hierarchical intentions well. Ironically it was because of Volkov’s undisputed hierarchical position as conductor within the orchestra that he could implement Braxton’s multi-hierarchical ideas. It might have been much harder for me as an outsider to convince the orchestra to do so.

This institutional reality made it difficult to anticipate what to expect, but throughout the rehearsals and performances, it quickly became clear that most of the musicians of the orchestra were very happy to explore Braxton’s radical and experimental orchestral concepts. With Volkov’s assured guidance, complemented by the experience of the Ictus musicians in performing complex scores, the orchestra musicians quickly familiarized themselves with the ‘stable logics’ of Braxton’s written music. The craft of a professional orchestra gave a sharpness to the reading of the scores which was sometimes lacking in the previous performances I did, elevating Braxton’s music to new heights. Navigating these scores with up to three conductors in addition to giving rapid in-the-moment improvisative responses posed a bigger challenge for the orchestra musicians, but also here they quickly gained in confidence throughout the brief rehearsal process and the two performances.

In general, it is difficult to find qualitative standards of how to judge these performances, what ‘worked’ better, what was more ‘successful’, not in the least because there simply isn’t much performance history to compare it to. I therefore generally refrained from imposing value judgements on the quality of any given performance.25 My primary focus was to perform the music and to learn from those experiences. In retrospect I would still have liked to spend more time working on collective improvisation and, more specifically, to focus on listening as part of the improvisative act. This needs to be learned through playing and rehearsing, like any traditional orchestra piece. However, working purely on improvisation without a score, means there’s no clearly indicated 'double bar' or ‘end point’ to the rehearsal process. Allowing for this kind of ongoing musical and social process, which lies at the heart of any improvisatory practice, is something to which the institutional and hierarchised structure of the classical orchestra is generally not very well attuned. However, these performances offered a tantalizing glimpse into the possibilities when such institutional boundaries are transcended.

Afterwards, I sent out a survey to the musicians to ask about how they experienced Braxton’s experimental approach to the orchestra. The responses were unequivocally positive, describing it as very interesting, enriching, funny, and how they were surprised at how well it worked, given their little experience in improvised music. When asked whether they would like the orchestra to perform this repertoire more regularly, they all affirmed, one stating that “the orchestra has a responsibility to give attention to this kind of repertoire and make it more known.” Another musician expressed his experience of the project in detail, which I would like to cite at length here:

I loved the feeling of having a little bit of freedom in a normally very constrained world, the fact that I had the possibility to make choices and decide what I was going to play, or to not play, and also do experiments, try to connect with other players in language music, see if they respond or not. But also, as a very classical orchestra musician with no experience in improvisation, it was good for me to have the structure of the written music and the conductors, and not feel completely on my own. I knew that I was going to feel restricted in my improvisations, lacking imagination and reactivity, but it improved through the rehearsals and concerts, even if it’s of course a long process. From my point of view, it has been an extremely positive experience.

Final thoughts

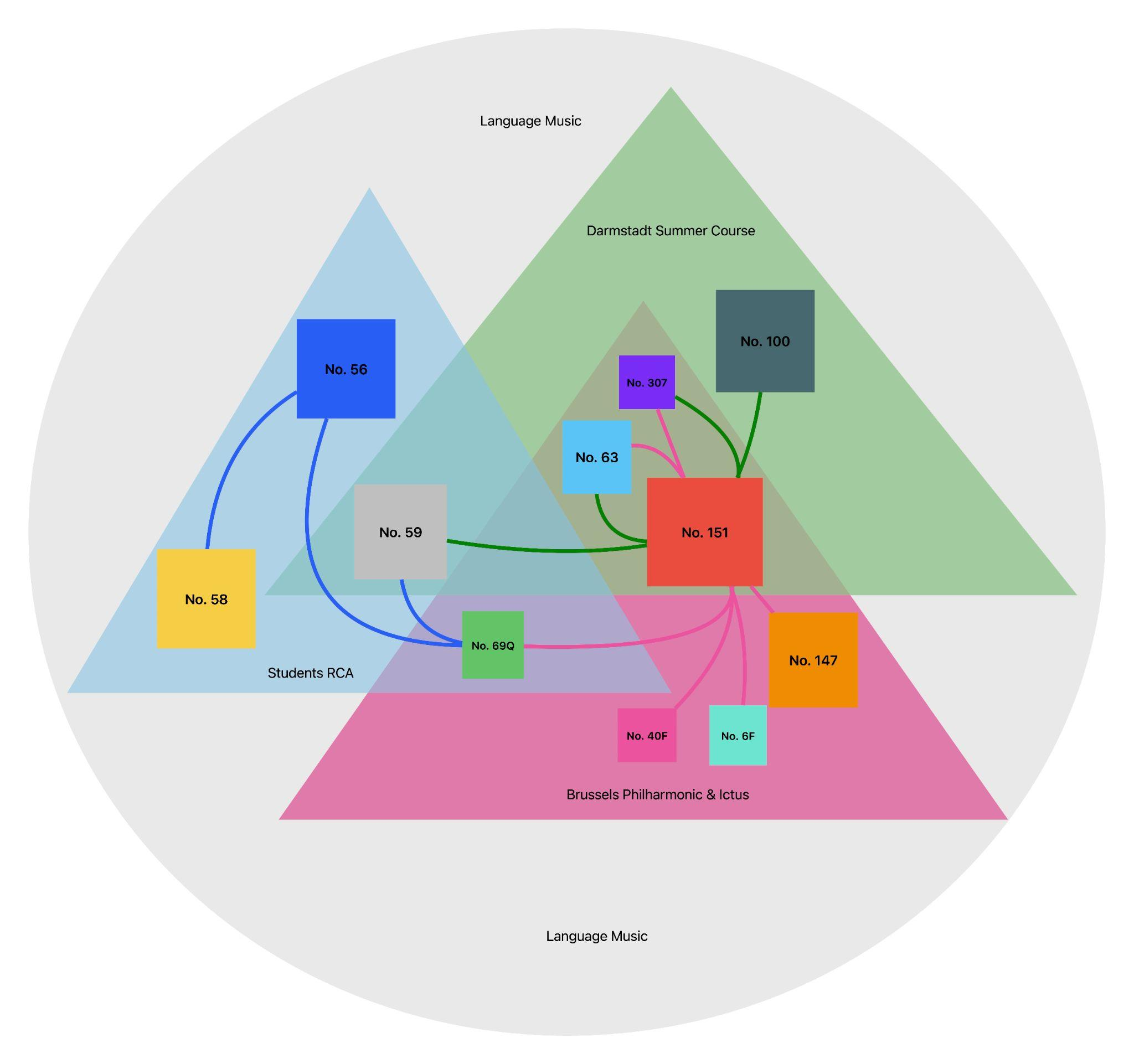

The three experiences with Braxton’s Creative Orchestra repertoire, as described above, generated vastly different results, but given the differences in context and eventual outcome, the performances retained a clearly recognizable Braxton aura as they were still very much connected within his musical philosophy of "Tri-Centric Modelling." Mapping out these three performances all together shows the navigational routes that were undertaken and how the different compositions connected and overlapped (see fig. f below).

Revisiting the recordings of the different performances clearly highlights Braxton’s fascination for orchestration and timbre, showing a deep affinity with a wide scope of orchestral traditions. The RCA student performance echoed the classic big band sound, reminiscent of Braxton’s renowned Creative Orchestra Music 1976. The Darmstadt Creative Orchestra, under Braxton’s own direction, became a nexus for young, global musicians, demonstrating remarkable individuality and collective orchestral experimentalism. The Brussels Philharmonic and Ictus engagements showed how this repertoire can equally find a ‘home’ in the hands of a symphonic orchestra, propelling both Braxton’s music and the classical orchestra into uncharted territories.

My primary goal in exploring this repertoire was to perform Braxton’s works the way he had intended it, regardless of what the artistic outcome would be, in order to contribute to establishing a performance practice of his Creative Orchestra concept. I therefore generally refrained from judging whether a given performance was better or more ‘successful’, but looking back at these experiences it is evident to me that a successful performance practice of these works should consider the fact that the artistic outcome is at least as much determined by the social process of preforming Braxton's music - and everything that entails - as it is the result of an interpretation of a set of written scores.

On a micro-social level, when Braxton’s musical philosophy and concepts are taken seriously, the Creative Orchestra becomes a small community that reflects society at large. The performers have the possibility to disagree and find ways to play in disagreement. The conductor(s) facilitate(s) the process, rather than lead it. It requires a great deal of mutual trust, not knowing where the music will take you.26 The ensemble's ability to operate in this manner significantly influences the musical result. It demands a unique discipline to cultivate a space of trust among a diverse group of musicians; a discipline that goes beyond playing the right notes and keeping time. Such dynamics resonate with broader institutional levels where the conditions can be enhanced to allow for this level of trust and the kind of socio-musical interaction that Braxton proposes.27 I witnessed how removing the genre barrier between the jazz and classical departments within the Antwerp Conservatoire opened up new possibilities for student orchestras to operate in a general sense of openness beyond the expectations imposed by such genre boundaries. Braxton’s presence at an internationally important festival such as the Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt forged a historic setting for a workshop centered on his Creative Orchestra Music, engaging young participants from around the globe. Having worked with Braxton directly, this experience in turn paved the way to undertake an equially historical multi-hierarchical performance with the otherwise very strict hierarchical structure of the symphonic orchestra. Once these conditions were met, I witnessed a great willingness among the orchestra musicians to explore Braxton’s radical ideas for the orchestra.

In short, these three practical experiences were a confirmation that performing Braxton’s repertoire, applying his multi-hierarchical strategies, and exploring the combination of composition and improvisation in an orchestral context offer an enriching perspective on what orchestral practice can be. When Braxton’s terms are taken seriously both on the local level among the musicians as well as on a higher institutional level, there are no limits to what the orchestra can achieve.

Below are pictures from the performance in Darmstadt as well as from Bruges and Antwerp (with Ictus and Brussels Philharmonic). Pictures from the performance with students from the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp, can be found here. Go to the Creative Orchestra Event Space to find recordings of all the performances.