6. ANALYSIS OF TERMS

a. Prelinguistic related terms

a.1. Babbling language is another way to describe the child’s prelinguistic steps. It is the stage in which babies practice sound production. It visualizes the sound which is “babbly” and repetitive. Of course, the creativity observed in the child language is not pure creativity or invention out of nothingness. It is, however, neither a pure imitation or a mechanical involuntary adoption. The child creates as it borrows. A very interesting approach to this topic is made by Lacan and his “Lalanguage” (see chapter 11.4.).

a.2. Exclamations and Interjections (also common in linguistics). Daniel Heller-Roazen makes an interesting approach to the idea of exclamations and interjections. He calls them “speech acts” with no representative action, or, linguistically speaking, distinctive anomalous phonological elements, which do not belong to the set of a language's sounds. They are “excess of phonology” of a specific tongue. Their function depends on the force of their utterance. He believes that, especially children's exclamations are the remains of their babbling language – for example the sounds used to imitate animals or mechanical noises.

There are also such interjections' (brief words or phrases) examples in adult's language, such as click sounds which trigger horses' movement, or the interjection “brrrr” used for cold. The usual result is onomatopoeias, by which humans imitate what is not human. Heller-Roazen concludes that “nowhere is language more itself than at the moment it seems to leave the terrain of its sound and sense assuming the sound shape of what does not – or cannot – have a language of its own. The language opens itself to a non-language that precedes it and that follows it”. (Daniel Heller-Roazen, Echolalias, Zone books, 2025, page 18) In this way, interjections and exclamations become the cells which preserve remnants of the prelinguistic language and show that language is a continuum (see also chapter 11.3).

a.4. Echolalia (also common in aphasic disorders) is the repetition of phonemes, words or patterns. It is a mimetic behaviour taking place without actual consciousness of the action. It is related to cases of aphasia and to children's behaviour before they acquire actual speaking abilities. Echolalia derives from the Greek words “ηχώ” = Echo and λαλιά = speech.

a.5. Inner speech (also common in aphasic disorders) The term belongs to Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and describes a kind of sub-vocalized speech. It is based on the dipole of external/social vs inner speech. Inner speech can take many forms, met both in children and in aphasic people. A standard situation in young children's life where inner speech is met is connected to the moment they go to sleep. It happens that, by speaking to themselves, they say goodbye to their beloved ones, stating that they will meet them again tomorrow. It may sound sad, but this action is connected to speech evolution. Αs written ιn chapter 2.3, through words they learn to calm down their fears and instincts. Inner speech is also often observed in aphasic disorder cases, though, as Jakobson says, there is little information on the subject from a linguistic point of view, since these cases are, for obvious reasons, rarely exposed to linguistic analysis.

b. Deconstruction

b.1. Sound-based terms

b.1.1. Epirotic acapella music is already mentioned in chapter 1.1. as an important personal reference. It is usually a 4-role ancient pentatonic acapella vocal tradition which can be found on the mountains of Epiros. These 4 roles are the “partis”, the “klostis”, the “richtis” and the “isokratis”. The subjects of these songs deal with immigration, death, killing and many others such topics. It is usually sung by non-professionals. These 4-roles can be sung by as many people as it gets.

The main roles are:

(in Greek πάρτης - the one who “takes” the melody): The leading role which is responsible for the main singing line.

(in Greek κλώστης which means weaver): This role “weaves” the melody around the main singing line, using words or phonemes of the main text, usually moving between the tonic and the sub-tonic.

(in Greek ρίχτης the one who “drops”): This role appears at the end of phrases making a descending exclamatory gesture, usually a perfect 4th lower than the drone.

Isokratis (the drone-keeper): The role who keeps the drone, “grounding” the sound.

The inspiration from this tradition varies from strictly musical elements that derive from it (drones, heterophony, exclamations) to the more general atmosphere of the isolated mountainous areas in which this style is met. “Grey earth, serpent” was conceived in this area, mainly while visiting abandoned stone villages, listening to the countless goat herds.

b.1.2. Heterophony is the simultaneous variation of the main melodic line. It is very common in Ottoman music, in which more than one instruments perform the same melodic line with varying embellishments.

A very typical heterophonic sound is the one produced by the combination of Partis and Klostis, in the case of Epirotic music. A very personal experience relates to listening to herds of goats of an Epirotic village, functioning as an atonal goat-choir, producing rough heterophonic textures.

b.1.3. Echo and distortion are sound phenomena which can also be applied in an a capella environment. A certain voice layer can, for example, at the same time distort another layer (see “Hecuba” analysis at the next chapter).

b.1.4. Ornamentation. The term widely varies according to the tradition we meet it. In Epirotic music, such embellishments are omnipresent. In my own music I am using the term in an “augmented” sense. Although ornaments are supplementary to a main music line, I often give them principal role.

b.2. Linguistics-based terms

b.2.1. Prosody.Τhe root word of “prosody” is "ωδή", which in Greek means song. According to Christopher Pluck, prosody is the “intonation contour” of an utterance. In general, prosody can refer to the direction of a phrase, the emotion, intention of what is being recited (question / statement).

Since I started working both in the frame of conventional theatre and ancient tragedy productions, one of my main concerns was to deal with the actors' voices, especially prosody. In many occasions I have composed their contours, speaking tessitura and dynamics. Actors are usually not trained in classical singing and score reading. On the other hand, they are more than flexible in being playful with their speaking qualities. From a personal theatre practice, the prosodic approach gradually developed into a primary vocal-based composition concern.

Musicologist Gary Tomlinson distinguishes prosody in “linguistic” and “affective”. The first is closely connected with grammar and syntax, whereas the second relates to the communicative emotive attitude. This latter is also connected to the ancient gesture-calls of the protodiscourse (i.e. the first human attempts for the creation of a language). It can involve acoustic aspects such as pitch or rhythm, but excludes phonology. The pitch fluctuation, the length and the rest of the contour’s information indicate the emotional expression. These intonations/melodies create a certain acoustic Gestalt.

It is also interesting that Tomlinson connects these “tunes” to the infants’ socialization, which creates a connection to the idea of Lacan’s Lalanguage (see chapter 11.4).

b.2.2. Lexiplasia is a step further than onomatopoeia. It results from the Greek words λέξη = word + πλάθω = create, which describes the creation of new words.

b.2.3. Shadow language is a self-invented term, based on the choice of certain syllables or phonemes from a word or phrase and the subtraction of the rest of the textual material. The chosen material, according to the general emotional and sound-texture words, form a secondary text, which sometimes exists as a heterophony around the main text, or, sometimes, as an individual entity.

b.2.4. Clouds is a self-invented sound-term, describing the creation of complex sound events, consisting of more than one voices speaking or singing at the same time. The aim is to create a sound event with clearly distinct components. At the same time, they should be perceived as a thick block with its own character.

b.3. Law based terms

b.3.1. Specificatio is a term which comes from the field of law (property law). The Greek version is Eidopoeia with its roots in the words είδος = genre + ποιώ = create. It describes the process according to which someone transforms a thing (res) into something new, to such an extent, that the value of the transformation is higher than the value of the thing (for example a sculptοr's work on a piece of stone is worth more than the piece of the stone itself).

This term accompanies me since my law studies, because, in a broad sense, when applied to music, it describes new entities produced through the interaction of smaller units.

b.4. Nature-based terms

b.4.1. Geophony is a sound layer consisting of the sound of the natural world (wind, rivers etc).

b.4.2. Biophony is a sound layer consisting of the sounds of living organisms (birds, goats, cows). The sound of goat herds is an important sound metaphor for two pieces that will be analyzed in the next chapter.

b.5. Gesture-based approaches

An important part of the sound material produced, in the context of the pieces discussed, is “gesture-based”. A musical gesture could be described as a “sounding movement”.

According to Garry Tomlinson, the first gesture-calls (see term b.2.1.) appear at the Acheulean period (1.7 million until 200.000 ago). These gesture calls originate from animal vocalizations that slowly passed to humans through mimesis. These gestures gradually turned into meaningful utterances which then developed into grammar. Their acoustic nature is said to be onomatopoeic. Gesture calls include laughs, sighs, groans, in other words, exclamations, which are also referred by Roman Jakobson as “the cells” that preserve prelinguistic language (see term a.2.). Gesture-calls are less “versatile” than words, with limited semantic possibilities, since they do not signal anything beyond their internal state.

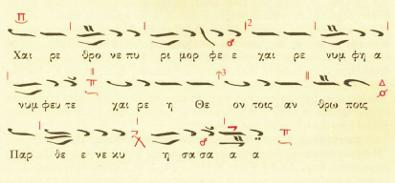

b.5.1. Byzantine quality characters

While the gesture-based theatre practice was developing, my interest in Byzantine music had begun. Historically, Byzantine music is vocal, also based on the experience and (within stylistic limits) the improvising skills of the chanter.

Byzantine music has been developing ever since its first appearance. Archbishop Chrisanthos, who introduced the current Byzantine notation, writes in his treatise, published in 1832: ''Ichos (in Greek meaning sound) is ’’ψόφος’’ (In Greek meaning ‘’sound’’ and ‘’death’’ as well) coming from living and lifeless creatures. ‘’Ψόφος’’ is the passion of rapped air caused by falling objects...Musicians, from time to time, imitate these "falls''. This definition of music belongs to Aristotle, and is found in his work “on soul, book 2, chapter H”.

Looking, again, at the linguistic level, in Byzantine music practice, the western term of ‘’cadence’’ corresponds to the word ‘’κατάληξη’’, which means ‘’ending’’. The western ‘’rest’’ corresponds to the Byzantine ‘’σιωπή’’, which means ‘’silence’’. The sign which indicates double or triple speed is called ‘’γοργόν’’, which means ‘’fast’’. There are more examples in which terms of everyday experience are directly transferred to the music without the use of any technical curtain. These are indications found on the linguistic level, showing the linguistic “physicality” of this music tradition.

The music characters (the notes) give clear indication not only about the pitch, but for the interpretation as well, which is up to the chanters. This leaves space to the approach and the aesthetics, of the chanter. Even more, Byzantine music remained purely sung, not played by instruments, which kept it closer to the human experience (Georgios Kiriakakis, Composition and Contemporary Music in the department of Music Art and Science, University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki).

Example of the Byzantine notation system

The ''characters of quality'' or ''expression'', are also called ''χειρονομίες'', which is translated as gestures. In addition, this Greek word also indicates the movement of the hand which shows vocal ornaments and shapes. It actually took its name from the gesture-showers of ecclesiastic choruses, who used their hands to indicate the direction of the gesture that was hiding in the old system of Byzantine notation (before 1832). In the treatise of 1832, which was already mentioned, many of these gestural characters disappeared, since the quality characters became were strictly notated.

This pool of information, the gestural approach, the space for improvisation and the physicality of Byzantine music, drew my attention and triggered my inspiration for the development of the gestural approach.

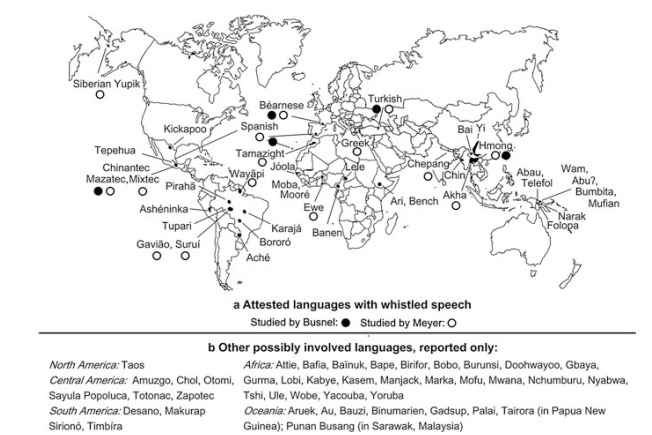

b.5.2. Whistling languages

Another important reference are the so-called “whistling languages”. Byzantine music, no matter how “physical”, remains a concrete music system with deep technical roots. I had been thinking for a long time what could be a new source for material and inspiration to this direction. An answer came some years ago from a small mountain village 3 hours from Athens, on the isle of Evoia, where an ancient tradition is still kept – the “whistled language”.

The village is called “Antiá” and their language is called “Sfyria”. Whistled languages are preserved by Unesco as the world's most endangered languages. In Antia there are about 20 people remaining who still know this type of communication. The way people in this village communicate was discovered in 1969 when an airplane crashed close to the village. Rescuers heard the whistles and that's how Sfyria became broadly known. A theory says that this communication code goes back to 2.500 BC, to the Greek-Persian war. After their defeat, Persians had to find shelter on the mountains. They are supposed to have communicated this way to avoid being understood by the Greek enemies. The residents of this village are supposed to be Persian descendants. Another source attributes this theory to the effort of this village to separate itself as having a unique-origin”.

There are few more places in the world with similar communication traditions.

This language is also called the “language of birds”, because of the obvious connotation. Julien Meyer has done great research on the subject, from a linguistic point of view.

Whistled language is a perfect pool of sound information, as a combination of an instinctive communication code with refined sound quality, intact through the centuries. I had the honour to have an extensive conversation with Panagiotis Tzanavaris, the founder of the whistling language corporation for the preservation of the Greek whistling language “Sfyria”, in June 2023. He believes that the roots of this language relate to the morphological characteristics of the place. It is not a coincidence that all the areas in which whistled language has been developed are rough and mountainous. People working as breeders lead their herds to steep and isolated areas, and this is the communication code they developed, to be heard along big distances.

Whistled language is a spectacular human creation that combines the instinctive need for communication with musicality, but, without any musical intention. A musical event is brought up, without the intention of being musical. It is a case in which the sound is strongly attached to the semantic aspect it serves. The grammar and the syntax of the language is completely adapted to the whistling system. There is, as it seems, a collection of contours and “ways” to communicate. Certain skills are needed, since, for this type of whistling, the larynx, the teeth and the lips coordinate. According to Panagiotis Tzanavaris, with some months of training, a native Greek speaker will manage to whistle the Sfyria.

Another interesting factor is the frequency band of all of the whistling languages. It has been found to be between 0.9 to 4 kHz, much less than the frequency band covered by the human voice (0.1–16 kHz).The pitches of whistlers are concentrated in a narrow bandwidth where the hearing in human beings is more sensitive and selective. These “concentrated” in terms of bandwidth, signals, form a narrow-pitch universe, which is also inspiring for developing music gestures concentrated in a narrow bandwidth (see piece “Shadows for a while” analyzed in the next chapter).

Whistling languages are secondary (derivative) language systems, based on the primary language of the country in which they have been developed. Nevertheless, it is impossible to ignore the musicality of the additional (whistled) information. On the one hand, sound becomes the vehicle to convey information. I cannot help thinking what would happen If one would isolate these contours, these music lines, from their semantic information. They would then turn into a kind of an a-semic language reminding of the wordless open-form writings of the Argentinian Mirtha Dermisache.

Without the semantic aspect of the meanings conveyed, the whistling language would remain a collection of colourful contours in a spectrogram. They could be used as tool for the construction of motives, or even larger-scale forms. Whistling language is a tool, but a metaphor as well, that opens up a new window to the concept of sound gesture, especially in relation to its semantic (non) aspect.

b.5.3. The use of symbols

At his last big venture before his death, Carl Jung writes “man and his symbols”, together with close associates of his. In this book, Jung brings together symbols, mythology and his theory of the unconscious, summarizing and bringing together the most important aspects of his theory. He discusses symbols as the key which unlocks meanings of our dreams, belonging to humans' collective unconscious. As Carl Liungman writes, the meaning of a symbol is something collective.

My engagement in theatre practice and prosody and the gradual visual representation of sound, brought up the general idea of the “shape” as a tool. The influence of Byzantine music and its quality characters, which are basically directions-shapes, gradually made this aspect more important in my work. Jungs' writings, together with all my pre-existing thoughts on shape and gesture, turned my attention to the shape per se, even more to the idea of symbol – a shape with a global archaic meaning.

c. Linguistic castration

c.1. Secret languages exist within the dynamic process of linguistic castration. It can be seen as a “stasis”. There have been cases that young speakers preserve and resist every attempt of passing from the prelinguistic stage to mature speech. This can lead to the creation of a separate, “frozen” language. This is observed in cases of siblings living in relative isolation. Roman Jakobson describes the case of an isolated Estonian farm, in which three brothers, between the age of 5 to 12 retained the speech of their early childhood. In other cases, the siblings can speak the adult language fluently, but maintain this “frozen” language, their “secret language” as a well-kept secret.

What follows are 3 case studies which relate to the concept of secret language creation:

c.1.1 The Louis Wolfson case is an impressive example of the creation of an own personal language. Sadly this was done because of the schizophrenic tendencies of Louis Wolfson (1931-). The story starts in the first years of his life, when he gradually developed such a resentment to his mother, that he couldn't even listen to the English language (his mother's and his native language). He trained himself in French, German, Russian and Hebrew and developed mechanisms / filterings that led to instant phonetic transformations of the English language. Whenever he would listen to an English word, a mechanism, often passing through more than one languages, would take over, processing the word and transforming it into a hybrid word, so that he could manage listening to it. Surprisingly enough, he describes these processes in detail in his book “Le Schizo et les langues” (Le Schizo et les langues, Louis Wolfson, Gallimard, 1970).

Wolfson imposed on himself a self-exile from his mother tongue, by creating a secret language, in order to make his life tolerable.

c.2.2 Hildegard von Bingen's “Lingua Ignota”. Glossolalia, angelic language, secret codes, are references to her so-called “uknown language”. Hildegard von Bingen created an own alphabet in order to represent it. Latin, Greek, old Hebrew, Cryptography are amongst the nuances traced.

Hildegard herself writes about her words' inventions: “I do not hear them with my outer ears or perceive them by the thoughts of my heart or by any combination of my five senses, but only in my soul, with my eyes open. So I never suffer that defect of ecstacy, but I see them day and night, wide awake”.

There is a long list of all her invented words. Here are some examples:

aieganz = angel

amzia = wasp

arrezenpholianz = archbishop

bizioliz = drunkard

fuscal = foot

loifol = people

maiz = mother

peueriz = father

scaurin = night

This is an example Hildegard’s language application to music. The word ‘loifol” (=people) is the only one directly coming from lingua ignota. The rest of the words are not found in her vocabulary, which possibly indicates that the list was larger.

O orzchis Ecclesia, armis divinis praecincta, et hyacinto ornata, tu es caldemia stigmatum loifolum...

(translation by Barbara Newman, 1987)

O measureless Church, girded with divine arms and adorned with jacinth, you are the fragrance of the wounds of nations...

Language invention and poetical distortion of the natural language is an existing, not only contemporary process. James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, even Tolkien, who, with his linguistic background in Germanic languages, created a whole new “elvish” language, through “glossopoeia” are some famous examples. Claude Vivier is known for entering the field of "language invention", in the piece "Kopernicus".

In Middle Ages, female language invention was connected to curse or schizophrenia. The theme of ecstatic speaking has been very dear to operas (eg Monteverdi’s Arianna, Donizetti’s Lucia) and contemporary music as well. In his piece “Infito Nero”, Sciarrino creates a haunting sound-environment, in which Mary Magdalene De Pazzi (1566-1607) spits out words when falling in ecstasy.

c.3.3. Glossolalia. The term results from the Greek words γλώσσα = tongue and λαλιά = speech. It literally means “speaking in tongues”. It is a practice met mainly in Pentecostal Evangelical church, according to which the possessed speaker creates sounds / phonemes / words of divine origin. It is actually considered to be a divine language, an ability to use language that normally the speaker does not know.

It was a common thought within the Greco-Roman world that divine beings spoke languages different from human languages. These languages are reminiscent of glossolalia, sometimes explained as angelic or divine language, mentioned also in the case of Hildegard von Bingen. Glossolalic phenomena are said to have occurred within the ancient Greek world, such as Eleusinian mysteries.

Carl Jung also refers to glossolalia as part of a patient’s ecstatic trance: “In reconstructing her somnambulistic ego we are entirely dependent on her subsequent statements, for in the first place the spontaneous utterances of the ego associated with the waking state are few and mostly disjointed, and in the second place many of the ecstasies pass off without pantomime and without speech, so that no conclusions about inner processes can be drawn from external appearances. S.W. is almost totally amnesic in regard to the automatic phenomena during ecstasy, in so far as these fall within the sphere of personalities foreign to her ego. But she usually has a clear memory of all the other phenomena directly connected with her ego, such as talking in a loud voice, glossolalia”.

d. Aphasic disorders

Before becoming specific about the terms and how I used them, it is useful to briefly mention the main types of aphasia and their general characteristics.

Broca's aphasia: Broca's aphasia acquired its name by Paul Broca (1824-1880), one of the first researchers in the field of aphasia. Broca found out in which part of the brain speech is created. Also named “motor aphasia”, by its definition it shows that not all speaking abilities are lost. Patients' difficulties include the struggle to use many words coherently, stumbling, or limited vocabulary. It is also called non-fluent aphasia.

Wernicke's aphasia: Carl Wernicke (1848-1905), was another significant aphasia researcher. This type of aphasia completely affects speech, since patients rearrange it in a way that it cannot be understood, creating a so-called “logorrhea” stream, an unstoppable stream of thoughts triggered by the patient's situation.

Anomic aphasia: Patients have difficulty in finding the right word when they speak or write.

Global aphasia: People with this type of aphasia have difficulty in putting many words together, and, sometimes, they have comprehension issues. They neither read, nor write.

Related terms

d.1. Logorrhea (metioned in Wernicke aphasia)

d.2. Stuttering is the difficulty of creating coherent meanings, resulting in repetitions and stretched sounds.

d.3. Apophenia is the tendency to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated things (Carroll, Robert T., The Skeptic's Dictionary online). Apophenia is related to schizophrenic disorders and conspiracy theory tendencies.

d.4. Alalia results from the Greek words “α” standing for “not” and λαλιά=speech. It describes a complete inability to speak.

d.5 Types of speech amnesia (common also in linguistics) Other terms related to aphasia, mentioned by Jakobson, (obsolete, but still, triggering my personal sound experimentation) are:

d.5.1. sound amnesia – refers to sound disturbances. The patient cannot separate two words with close sound but different meanings.

d.5.2. word amnesia – refers to word meaning confusion. Words with close meanings replace the correct word. For example, Jakobson mentions a case in which a patient substitutes every word that describes a useful activity with the word “to build”.

d.5.3. agrammatism – refers to the tendency for grammatical and syntactical errors.

If, despite these disturbances, the brain's functions are still retained in a weaker stage (reminding us of the unconscious) then three new sub-categories arise:

d.5.4. sound paraphasia

d.5.5.verbal paraphasia

d.5.6. paragrammatism

In all these cases, the semantic aspect of the linguistic units is injured: The distinctive value of the phonemes, the lexical meaning of the vocabulary, grammar and syntax of a language.

This meaning's or sound's disturbance both result in:

d.5.7. expansion of homonymy,

d.5.8. expanded ambiguity - polysemy of the word.

d.5.9. What also expands is paronymy (phonologically similar words), which happens because of the narrowing down of the phonemes and words used.

e. Terms applying to more than one specific fields

e.1. Redundant sound information (common in the prelinguistic stage, whistled languages, and sound-based terms)

Jakobson states that “It is impossible to explain the perception of speech isolated from the pitch variations and noises”. From another point of view, the same approach is found in Meyer's book on whistling language. Meyer says that “background noise is ubiquitous in natural environments. Rural background noise is known to be rather variable, even when it does not include mechanical sources of noise. This depends on the geographical situation, the terrain, the vegetation, meteorological circumstances, bio-noises such as animal calls (biophony) and hydronoises such as rivers or sea rumble (geophony)”. He refers to this layer of sound as an organic element of the general soundscape in which whistling language exists. The same thought is supported by the fact that speech anyway has a lot of redundant information. We can low-pass or high-pass filter it, 100% below, or 100% over 1500Hz and still recognize 100% what is being said.

The conception of “geophony” (2.4.1.), “biophony” (2.4.2.) and “redundant speech information” is an approach to the sound phenomenon as a totality. In all of the three cases sound cannot be isolated from its natural environment.

e.2. Classes of sound perception (common in sound-based terms and aphasic disorders)

Jakobson writes that pitch variations in sound phenomena can result in three different categories:

-sounds as musically utilized sound phenomena (music)

-sounds as linguistically utilized sound phenomena (speech)

-sound phenomena which have neither musical nor linguistic value, still acting as simple marks or different sounds (eg street noise)

These observations can be connected to the ideas of Sprechstimme and Sprechgesang. The distinctions of pitch can vary from musical values to elements of differentiating meaning, especially in tonal languages. In the first case we perceive intervals, musical motives, scale components etc. In the second case, we perceive linguistic fluctuation, statements, questions, even meaning's differentiation.