Assembling a Praxis:

Choreographic Thinking & Curatorial Agency

Lauren O'Neal, University of the Arts Helsinki

Research Summary

(2022)

Note: This document—which can be found in each exposition (this is the most recent version)—was intended primarily for the doctoral pre-examination process. Much of the content can be found in the dissertation. Read the summary if it's helpful. Otherwise, feel free to go back to the Being & Feeling (Alone, Together) exposition from the landing page.

This Research Summary is also available as a PDF.

Introduction

My research centers on choreographic thinking within curatorial practice, with a specific focus on curatorial process. Choreographic thinking, for me, is characterized by movement and arrangement, embodiment and encounter. What happens when you curate from this position?

My curatorial work is part of an expanded art practice, which includes creating objects and performances, teaching, and developing cultural programs—situations that encourage others to make, view, and experience the arts. Each activity informs the other in an ongoing, indirect feedback loop. My methodology is in conversation with durational and spatial art practices, including installation and dance, among other disciplines, but the primary focus is on my curatorial projects: how they are produced via a choreographic ethos, and what they might produce, in turn.

Choreographic curation is exploratory in spirit, responsive to context, and open-ended. The choreographic allows potential (action) to infiltrate the curatorial, shifting it to an activation instead of an answer. Curation under these conditions becomes an embodied form of inquiry: a way to ask questions, make introductions, and invite possibilities, using the platform of the gallery space as laboratory, rehearsal room, studio, and stage. It seeks, rather than seeks to answer.

Making, Movement, and Meaning

As a curator, I consider questions of composition, space, time, interaction, and agency. My interest in the choreographic emerged when I began to pay more attention to the connections between my dance and movement practices and my work in the studio—activities that have been concurrent, but rarely connected. My involvement as a performer in museum and gallery-based performances has also contributed to my research.

I have gained insights about curatorial practice from participating as an audience member and contributing artist in a variety of settings. Influences include visiting an exhibition of the collaborative photographic work of Wendy Ewald at the Addison Gallery of American Art, attending a production of Athol Fugard’s The Road to Mecca, being immersed in the expansiveness of Fred Moten’s lectures, experiencing Ann Hamilton’s Event of a Thread at Park Ave. Armory, threading my way through clothes while hanging upside down in Trisha Brown’s The Floor of the Forest at the Institute of Contemporary Art’s Dance/Draw exhibition, and leaning forward in anticipation while watching Einstein on the Beach 36 years after it was first performed, among other experiences.

Doctoral artistic research has been an opportunity to connect these areas of inquiry, and to develop insights about how these practices (moving, making, participating, curating) intersect and inform each other.

I do my aesthetic thinking and making through movement: it spatializes my awareness and gives room for concepts to emerge, assemble, and rearrange. My artistic research practice is hyphenate: moving-thinking-making-seeking-mapping-building-writing-arranging-researching-experimenting-configuring-assembling-testing-tweaking-assessing: a choreography of intersection.

Erin Manning sees the hyphen as a generative force, a differential that “brings making to thinking and thinking to making.”[1] She argues:

Different practices must retain their singularity… when they do come together…it is important to inquire into what the hyphenation does to their singularity. We find research-creation to be a fertile field for thinking this coming-into-relation of difference. Problems that arise include: How does a practice that involves making open the way for a different idea of what can be termed knowledge? How is the creation of concepts, in the context of the philosophical, itself a creative process?... In what way does the hyphen make operational interstitial modes of existence?[2]

The role of intersection is key: within the gallery, I arrange elements of exhibitions into relational configurations to delineate possible (overlapping) territories.

Drawing From/On/Alongside: Dance, Performance & Curating

My investigation contributes to a broader discourse around the ways the visual arts and the performing arts intersect: the shared histories, methods, or vocabularies, how different domains together produce new, interdisciplinarity art forms, and how creation and reception shift when activity in one domain is theorized or produced through the mesh of another.

This project benefits from recent writing on curation that address connections between curation and performance, as well as select texts and activities from the fields of museum studies, architecture, museology, poetry, and queer studies, among other sources.

Recent curatorial theory on curating and performance includes Maren Butte et al., Assign & Arrange: Methodologies of Presentation in Art and Dance and Florian Malzacher’s and Joanna Warsza’s Empty Stages, Crowded Flats: Performativity as Curatorial Strategy. This emphasis is also reflected in exhibitions such as Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done[3] at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (2018-2019) and Objects and Bodies at Rest and in Motion[4] at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm (2014). Although I am not conducting a comprehensive review of these discourses, I am in dialogue with their concerns.

While discussions of curation increasingly reference concepts and vocabularies from dance and the performing arts (and vice versa), many of these do not move past the singular case study. My research project was initiated because I was eager to develop these passing references into a more robust theoretical structure from which to develop and analyze my work.

Additionally, most of these examples focus on the implications of integrating the performing arts into museum settings. In contrast, my project examines what it means to use aspects of performing arts discourse as a curatorial framework. I explore curating through and with the mesh of choreographic thinking (versus curating choreography in museums), and consider how that impacts the process, and potentially the outcome, of a curatorial project.

When the Curatorial Becomes Entangled With the Choreographic

Maria Lind, Beatrice von Bismarck, Paul O’Neill, and others have written about ‘curating’ and ‘the curatorial,’ and what the expanded field of the curatorial might entail. These notions are already entangled with the choreographic.

Lind proposes the curatorial as a methodology, such as that used by artists in postproduction, drawing from “the principles of montage, employing disparate images, objects, and other material and immaterial phenomenon within a particular time and space-related framework.” She concedes that this activity has choreographic aspects, as it “includes elements of choreography, orchestration, and administrative logistics—like all practices that work with defining, preserving, and mediating cultural heritage in a wider sense.”[5]

The (choreographic) curatorial also emphasizes the encounter. Beatrice von Bismarck and Benjamin Meyer-Krahmer underscore the relational aspect of the curatorial (emphasis added):

A curatorial situation is always one of hospitality. It implies invitation—to artists, artworks, curators, audiences, and institutions; it receives, welcomes, and temporarily brings people and objects together, some of which have left their habitual surroundings and find themselves in the process of relocation in the sense of being a guest. Thus, the curatorial situation provides both the time and the space for encounter between entities unfamiliar with one another.[6]

As Raqs Media Collective imagines this curatorial encounter as a collision: “We come face to face with the ‘curatorial’ whenever we witness within ourselves or around us the collision of artistic forms… Contact and confrontation, in art, as in life, are an occasion for the multiplication of misunderstandings, for epidemics of meaning.[7]

This curatorial focus on contact and encounter—the relational core of the curatorial—is echoed in theories of the choreographic. Jenn Joy observes, “To engage choreographically is to position oneself in relation to another, to participate in a scene of address that anticipates and requires a particular mode of attention.”[8]

An expanded notion of choreography makes way for the choreographic-curatorial: a situated partnership that is responsive to the environment and context. While this approach is an embodied one, Adesola Akinleye observes that it can happen with, but also beyond the body:

The orchestration of choreography appears to happen in, on and beyond the ‘body’ of the agent. Choreography conducts these partnerships, coming to be associated with dance because of the way dance so easily traverses doer, environment and onlooker. Choreography draws on qualities of observer/observed/felt to create affiliations of understanding (and communication) between environment, dancer, choreographer, and audience.[9]

The choreographic-curatorial considers not only the exhibition, but the motivations, contexts, and interactions of all the components, both logistical and conceptual. “Agents” in the curatorial encounter can be any motivating force, which is why Akinleye’s perspectives are so familiar to me as a curator.

Centering the choreographic within curatorial practice is strategy for thinking, or for structuring the event of thinking. It is a tendency—a way to be inquisitive—rather than a given set of protocols, reactions, and outcomes. Erin Manning notes that “a choreographic practice challenges the presupposition that movement is secondary to form, subjective or objective. The choreographic…is a technique that assists us in rethinking how a creative process activates conditions for its emergence as event.”[10]

To curate choreographically is not so much to curate dancing bodies in galleries, but to use movement, arrangement, and responsiveness to produce generative, exploratory, and open-ended exchanges of art objects, ideas, and people within an exhibition context.

My Own Curatorial Knowing and Being

In contrast to the representational aspirations of curating, Irit Rogoff notes that the curatorial is a “trajectory of activity”[11]—it is about the ongoing work of knowledge production (and the production of subjectivity as well), not the end-product: “The curatorial as an epistemic structure… is a series of existing knowledges that come together momentarily to produce what we are calling the event of knowledge.”[12]

Artistic research aims to produce new knowledge. This research project attempts to clarify what it is that I know in the curatorial realm. Knowledge in artistic research and choreographic curation is ongoing: a continuous activity rather than an arrival. How do you codify or capture this mobile knowledge? This question has come to encompass a wider concern with the choreographic qualities of artistic research.

Perhaps choreographic-curatorial produces what Simon Sheikh calls spaces for thinking: “Whereas knowledge is circulated and maintained through a number of normative practices – disciplines as it were – thinking is here meant to imply networks of indiscipline, lines of flight and utopian questionings.[13] Choreographic curatorial practice works in concert with artworks, artists, audiences, spaces, and situations, which each have agencies and epistemological territories of their own. This collaborative space-making can take the form of pedagogy, or community building, or political discourse. It produces effects in relation to agents beyond the curatorial field itself.

My own best curatorial practice is long-form, happening not just in one singular project, but over the course of many. It is most effective when it is embedded in a specific place. It is inherently about a regular encounter with a public, or with collective publics, with an awareness of institutional and social contexts.

To some degree, my project is as much an attempt to share a poetics of choreographic curation as it is an effort to prove that such a thing exists in the first place.

Methodologies, Themes, and Questions on Choreographic Curating

In this research, I theorize my approach to choreographic curation through the production and close examination of three curatorial projects produced while I was the director and curator at the Lamont Gallery at Phillips Exeter Academy. This situation allowed me to consider areas of my research as they appeared in different forms, over time. I had access to the process of curation in a way that simply looking from the outside at someone else’s curatorial work could not provide. Admittedly, this approach comes with biases, but this is an artistic endeavor, not a sociological one.

The projects serve as research methodology, research activity, and research outcome. The research unfolds through a series of loosely assembled gestures (rather than a set of repeatable steps). It is supplemented by ‘alongside’ research activities such as cultural production and performance. Collectively, these activities enable me to map and advance my practice.

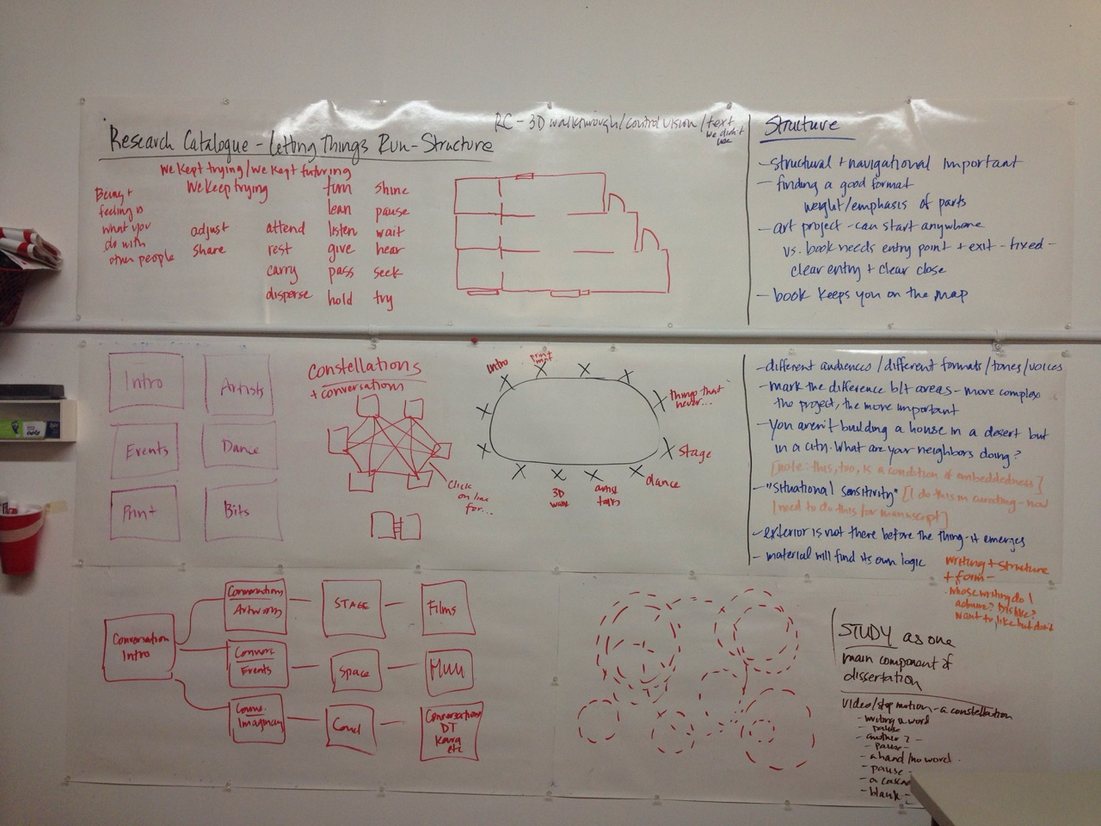

The dissemination of the doctoral artistic research includes the printed text (the thesis or dissertation) and the accompanying online expositions in the Research Catalogue, with reflective analysis in relation to project materials and exhibition images.

Themes and questions in this inquiry include:

What does choreographic thinking produce in the curatorial? What is the nature of the thinking process (material, spatial, textual, other) that contributes to the curatorial arc?

Knowing and being: What types of knowledge and non-knowledge can curating in a choreographic manner produce or encourage? What subjectivities arise?

Is there a curatorial dramaturgy? What kind of dramaturgical scaffold is possible or necessary when choreographic thinking drives curation?

The role of objects. What can objects do? Can objects or exhibitions be speech acts? Or choreo-acts? What is the object of knowledge, or research?

The temporal dimension of curating as understood as attention and intention. What is the impact of individual and institutional time, slowness, speed, and inaccessibility?

How does choreographic curatorial practice queer or recalibrate the process? Is there a ‘wayward curating’ that challenges or reconfigures normative systems of display, vision, and discursivity? How does curating resist?

The relationship between artistic research and choreographic thinking in the curatorial realm, including invisible and speculative research.

Assumptions & Conditions: What I Am Doing (and Not)

I am not completely derailing commonly understood notions of curation and exhibition development, but I am pushing at the boundaries to create more flexible structures.

My curatorial practice is set within specific, local settings, in non-commercial, academic, and non-spectacular spaces. I am not concerned at this point with the global art market, nomadic curatorial practices, the lure of the art star, or the biennial. Those trends undoubtedly influence all art practice today, but they are not my area of inquiry.

I am not overturning the institutions in which curating takes place. To some degree, I enjoy the challenges, and the structures, that institutional settings provide. I do not balance on these supports uncritically. In developing and enacting what I am claiming is a flexible, movement-centered curation, I do critique these ‘naturalized,’ static, and colonialist conditions of the gallery and the academic institution. I grant that they are inherently problematic. This body of research is to illuminate my own practice, and in doing so to lay the ground for future research that is outside the scope of this project.

I take artistic license with interdisciplinarity. I am in dialogue with different discourses, from dance and theater to poetry and architecture. I connect them in a loose weave to analyze and further my practice. I am most in my element when taking ideas from one domain and applying them, however inelegantly, to another. These awkward pairings—between the choreographic and the gallery, between the dramaturgical and the art object—are not made lightly. They are a way for me to move, literally and conceptually. They are a means for ideas to move.

Finally, I am not crafting a manual of curatorial practice. I disagree with the requirement that new knowledge is always something that can be easily communicated, scaled up, or reproduced. This project will likely expose gaps in my attempts to grasp choreographic curation, shortcomings in my ability to convey it completely, inadvertent omissions of details that I will not know to be important until years later, and full-scale chasms where a leap of faith will be required—an acknowledgement of shared, yet incomplete understanding: I kind of get it, you nod. (If I squint and tilt my head) I see what you mean.

A Lot Has Happened / What Happens Now?

A great deal has happened since the beginning of this project. We have been in a global pandemic for over two years. We continue to be surrounded by extreme civic and political discord and deeply entrenched racial and gender violence. We are living at the precipice of environmental catastrophe. We have experienced grief, loss, confusion, and uncertainty. Cultural institutions are struggling to address these profound structural inequities and redress the longstanding legacies of systemic exclusion. My doctoral research has been shaped by these recent contexts, even though I address them more directly in my work as an educator than in this specific research project.

These conversations are not new, but the pandemic has made them more urgent. I am not entirely convinced that the museum and curatorial practice are structures that can be decolonized. I suspect it is time for them to be dismantled completely.

Works Cited:

Akinleye, Adesola. Dance, Architecture and Engineering. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Butte, Maren, Kirsten Maar, Fiona McGovern, Marie-France Rafael, and Jörn Schafaff. Assign & Arrange: Methodologies of Presentation in Art and Dance. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014.

Forsythe, William, “Choreographic Objects.” William Forsythe: Choreographic Objects. Louise Neri and Eva Respini. Boston: The Institute of Contemporary Art, 2018.

Joy, Jenn. The Choreographic. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014.

Lind, Maria, ed. Performing the Curatorial: Within and Beyond Art. Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2012.

Malzacher, Florian and Joanna Warsza, eds. Empty Stages, Crowded Flats: Performativity as Curatorial Strategy. Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 2017.

Manning, Erin. Always More Than One: Individuation’s Dance. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

———. The Minor Gesture. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Raqs Media Collective. “On the Curatorial, From the Trapeze.” The Curatorial: A Philosophy of Curating. Edited by Jean-Paul Martinon. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Rogoff, Irit. “Curating/Curatorial: A Conversation Between Beatrice von Bismarck and Irit Rogoff.” Cultures of the Curatorial. Edited by Beatrice von Bismarck, Jörn Schafaff and Thomas Weski. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012.

Sheikh, Simon. “Objects of Study or Commodification of Knowledge? Remarks on Artistic Research.” Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 2, no. 2 (Spring 2009). http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n2/sheikh.html

von Bismarck, Beatrice and Benjamin Meyer-Krahmer, eds. Cultures of the Curatorial 3: Hospitality: Hosting Relations in Exhibitions. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2015.

[3] Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done, curated by Ana Janevski and Thomas J. Lax: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3927.

[4] Objects and Bodies at Rest and in Motion, curated by Magnus af Petersens and Andreas Nilsson: https://www.modernamuseet.se/stockholm/en/exhibitions/objects-bodies-rest-motion/.

[5] Maria Lind ed., Performing the Curatorial: Within and Beyond Art (Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2012), 12.

[6] Von Bismarck, Beatrice and Benjamin Meyer-Krahmer, eds. Cultures of the Curatorial 3: Hospitality: Hosting Relations in Exhibitions (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2015), 8.

[7] Raqs Media Collective, “On the Curatorial, From the Trapeze,” in The Curatorial: A Philosophy of Curating, ed. Jean-Paul Martinon (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 18.

[10] Erin Manning, Always More Than One: Individuation’s Dance (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 7.

[11] Irit Rogoff, “Curating/Curatorial: A Conversation between Beatrice von Bismarck and Irit Rogoff,” in Cultures of the Curatorial, eds. Beatrice von Bismarck, Jörn Schafaff and Thomas Weski (Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2012), 23.

[13] Simon Sheikh, “Objects of Study or Commodification of Knowledge? Remarks on Artistic Research,” in Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 2, no. 2 (Spring 2009), http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n2/sheikh.html