FIGURE 17 (top): Audio recorder

FIGURE 18 (middle): Contact microphone

FIGURE 19 (bottom): Condenser microphone

From the recordings I could gleam that the base of Fallen Tree A would be my best bet for a sound-based intervention in the wood. Its sound was the clearest. Around that point were also a collection of holes going into the trunk, indicating hidden chambers. Further, I could speculate on the development of rot in the trunks. If I was right in assuming that the rot spread from the base of the tree, then the wood would be denser and less decayed towards the top. The recordings of trunk B reaffirmed me, with dense and flat sounds. The breaking point of the fallen part of tree A is riddled with holes made by the rot, but not in nearly as a developed stage as its corresponding stump. A person could sit inside the hollow of the stump. One could barely put a hand into the breaking point of the fallen tree (figure 21). I could only imagine the cavities would be smaller further along the trunk.

Eventually I walked back to the site and found it empty. I could begin. As shown in the plans for recording, I began by placing a contact microphone on a few spots along the length of the fallen trunks (contact microphones pick up the vibrations going through material, instead of vibrations in the air). With a headset plugged into the recorder I spent the first few minutes of recording by listening to each spot. I heard nothing. It was slightly discouraging. Afterwards I proceeded to knock on the wood around the microphone with a stick. I imagined it would tell me something about the way the wood conducted sound. I did this on five spots.

A group of children were running around the trees when I arrived. They balanced on them, shouted into the tree stumps and beat the logs with long branches. I hesitated for a moment. They were doing exactly what I had come there to do. It made me glad to see that the trees appealed similarly others as well. Not wanting to linger around until they left, I trailed off on another path until I found a bench where I could wait. By the base of a tree next to the bench someone had scattered a collection of objects. Flowers, small lanterns, a miniature statuette and an illustrative plastic dog head on a stick (figure 20). There was a laminated note among them. On grid paper, as from a math book, big handwritten letters spelled Six months in heaven. A grave. I was looking at the burial site of a family pet.

With an audio recorder and a couple of microphones I intended to listen to the dead trees. I wanted to find out if they produced any ambient noise, and how they would conduct sound. This information would make it easier to discern the optimal placement of microphones for recording the actions I had planned.

The next step was to record the sound inside the holes of the tree with an external condenser microphone connected to the recorder (condenser microphones pick up sound in a 75-150-degree cone, making them ideal for recording a specific source of sound). First, I inserted it into a small hole close to the first contact mic recording. Then I lowered it into the hollows of the two stumps. At first, I was awestruck. I could hear the wind! I imagined the wind entering the wood through holes in the surface and passing via a network of tunnels until it reached the microphone. I saw the trunk like an enormous flute, with each of its holes modifying the wind to a different pitch. It eventually dawned on me that what I was hearing was not the wind through the trees, but the wind being picked up by the internal microphones of the audio recorder outside of the tree.

FIGURE 21 (top): Breaking point of the fallen trunk of Tree A

FIGURE 22 (bottom): Condenser mic in small hole on the trunk of Tree A.

The forest provides a type of solace which is scarce in large cities. No other public space gives the same sense of privacy and shelter. This shelter can even be found in a city park, for which only a few regulations prevent it being bulldozed to make room for high rises. It is a space that allows for deeply personal gestures. There we can play, wander and weep. Far away is the gaze of windows and the tumult of streets. Noise decreases there. The dizzying sound of traffic becomes a distant hum, merging with the whistling of the wind and birds. It is as if the trees capture sound and envelop it in bark. Under the shelter of a dome of leaves, light moves and changes as if shone through stained glass. In that light it is calm and silent. Yet there is more to it than that. The nearby graveyard is also calm and silent, but it is filled images of tradition and expectations. I am conditioned to asphalt, high rises and history. These things do not belong in the forest. In the forest I am only a visitor in someone else’s domain. It is the world of branches and undergrowth. The forest belongs to the trees. But among them we can find shelter.

1: Base of the fallen trunk A, contact mic on a patch of exposed wood: A clear, resonant sound within a ca. 30cm radius.

4: Two thirds the length of fallen trunk B, contact mic on exposed wood: A dense sound, like knocking on a wooden table.

As it turned out, it was not possible to switch them off while still giving power to the external microphone. For a moment I relished in an enormous potential, until my technical shortcomings disenchanted me. Regardless, with the recordings from the contact microphones I had the data I needed to plan further. On the plans below are the two projects I considered to be the result of my time on the site.

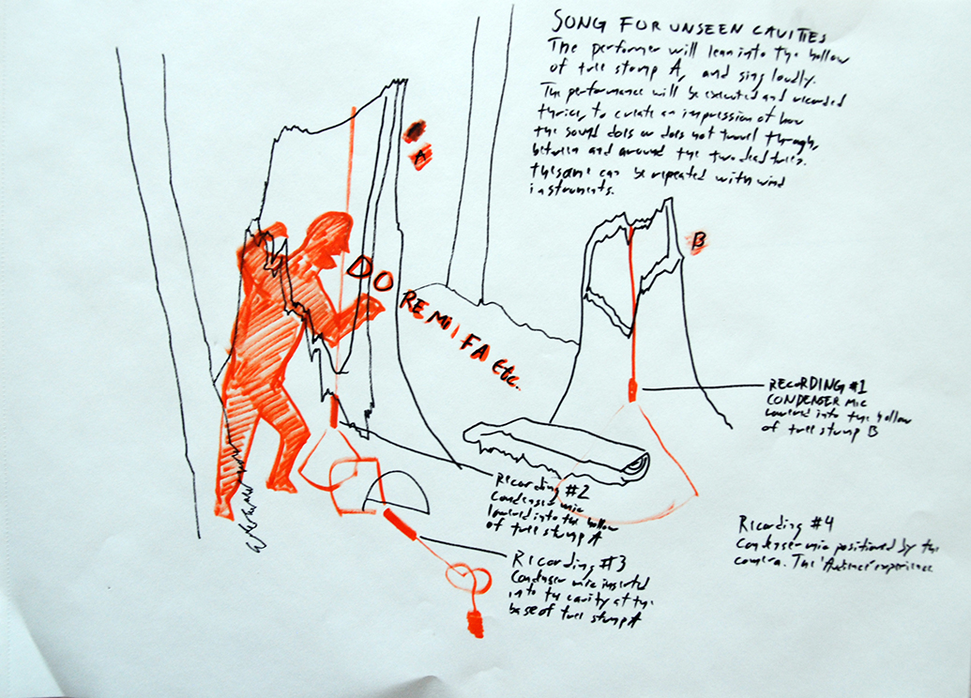

In Song for unseen cavities I planned on singing into the stump of Tree A. I wanted to find out how sound travelled in and around the trees. The action would be documented with video and sound recording. I would repeat the song four times, with an audio recorder in different locations each time. The frame of the video would focus on the location of the recorder. The locations were the inside the stump of tree B, inside the stump of Tree A, where I was singing, then in the small hole at the base of Tree A and finally at a distance together with the camera positioned to show an overview of the scene.

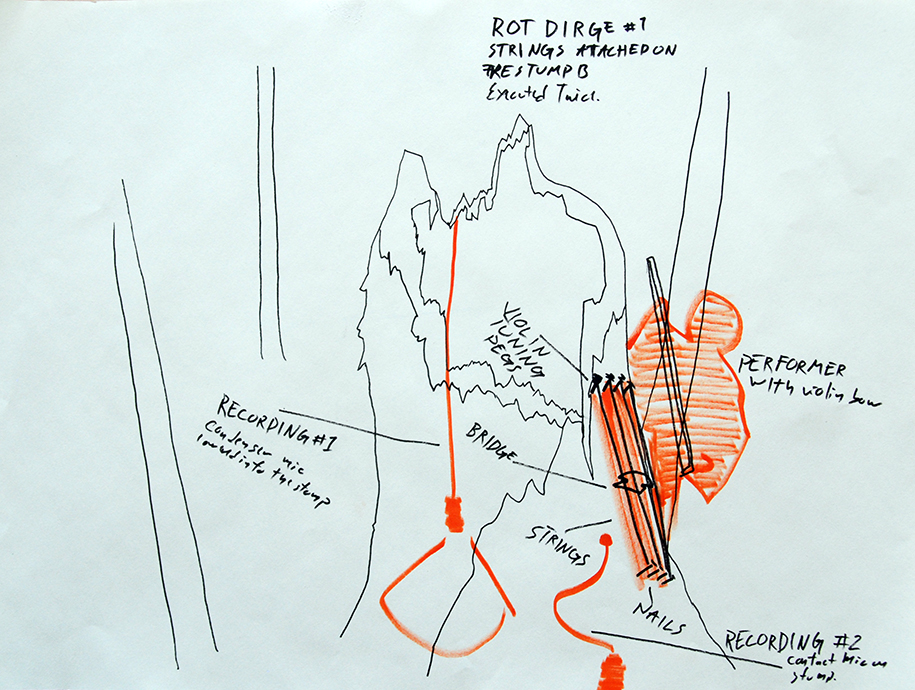

In Rot Dirge 1&2 I intended to attach violin strings to two different locations on the trees. The first being the base of the fallen part of Tree A. My recordings with the contact microphone lead me to believe that it was the spot most optimal for conducting sound. The second location was on the stump of Tree B. I was curious if the size of its hole would somehow amplify the sound. To attach the strings, I would drive nails into the wood on one end, and on the other drill holes in which I would insert tuning pegs. I planned on using a bridge I had made for another instrument to conduct the sound into the tree. With the strings in place I would improvise a tune recorded in a similar way to the singing.

A note on intervention

These actions, particularly Rot Dirge, involve imposing myself on the ecosystem present in the dead trees. I stand at the risk of disturbing whatever lives in there. If I had drilled holes in a living tree, I would have invited the very rot that felled the dead trees. In their current state, the dead trees are slowly decomposing. I trust that a few more holes will not interfere too much. In any case, developments in tree trunks happen so slowly that had I caused damage I would probably never learn of it.