As far as the musical repertoire of the time is concerned, secular music was undoubtedly the one most strongly characterized by the national “typism” so coveted by the Catholic Kings, especially the repertoire of amorous music that, at their time, had a portentous blooming. These songs with love lyrics were one of the greatest glories of the court of King Fernando and Queen Isabel, highly esteemed and typically Castilian. With three or four voices, alone or accompanied, but also for solo voice or purely instrumental, they were characterized by a simple technique and no artifice. This period also saw the amazing flowering that took place in the field of dance, which has always been the fulcrum of secular music. The alta and baxa dances were the favourite and best known in the court of the Catholic Kings, as well as in the Aragonese court of Naples and, practically, in the courtly environments throughout Europe (we remember the famous Belgian collection of Basses dances where we find a series of dances entitled Portingaloise, Navarroise, Barcelone, La Basse dance du roy d’Espagne).6 Together with the music, they accompanied the great majority of public and private events of the nobility.

In the field of sacred music, the Spanish monarchs always distinguished themselves for their commitment to making the music of their chapels as worthy as possible of “the honour and glory of God”. Here too emerge elements of “typism”. Even though they were not as strong as in secular music, they still represent a clear anticipation of what will be created later. Whilst the whole Spanish sacred repertoire of the late XV century resumes, as far as the musical forms and technique are concerned, the technique of the Flemish composers, the themes of its melodies were almost exclusively drawn from Gregorian melodies and not from profane songs (such as Adiu mes amours or L'ome armé).

This was the fertile climate at the court of the Kings of Spain, on which the rich Renaissance music of the XVI century would nurture its root and that Columbus’ followers will eventually help to project overseas. But let us have a closer look at some of the emergent figures who defined the environment of Spanish music on the eve of the great discovery that would forever change the history of two continents.

6 Higinio Anglés, La musica en la corte de los Reyes Católicos, vol. I-La polifonia religiosa (Madrid: Instituto Diego Velázquez, 1941), p. 62.

“The conquest of Granada and the discovery of the America represented at once an end and a beginning. […] Both reconquest and discovery, which seemed miraculous events to contemporary Spaniards, were in reality a logical outcome of the traditions and aspirations of an early age, […] the ideals, the values and the institutions of medieval Castile.”

John H. Elliott, La Spagna imperiale: 1469-1716 (Bologna: il Mulino, 1982), pp. 44–45.

On October 19, 1469, when they married at the Palacio de los Vivero in Valladolid, Isabella and Ferdinand were two young heirs to the thrones of Castile and Aragon, just eighteen and seventeen years old, respectively. In a few years, at the death of King Henry IV and against his late will, Isabella proclaimed herself Queen of Castile, anticipating the allegation by Juana la Beltraneja, supposedly illegitimate daughter of Henry IV (the Impotent!), who in 1475 claimed the throne for herself. After almost a decade of struggle for succession and civil war in 1479, the entire territory of the Kingdom of Castile was eventually in the hands of Princess Isabella. Ferdinand's ascent to the Aragonese throne in the same year led to the personal union of Aragon and Castile. Isabella and Ferdinand's marriage not only represented the first step for the reunification of Spain after centuries of divisions and internal fights but also opened the doors for a period of growing success for the country, which would eventually elevate Spain to a dominant world power.

Under the rule of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Spain of the last quarter of the XV century was politically and culturally homogenized under the flagship of Catholicism. The introduction of the Spanish Inquisition in 1478, the reconquest of Granada from the Moors and the order for all Spanish Jews to convert to Christianity or face expulsion in 1492, followed by a similar order for Spanish Muslims four years later, created the internal conditions that would make possible the forthcoming colonial activity and would lead Spain to an époque of great prosperity and imperial supremacy.

It will be in this atmosphere of a cultural and economic renaissance that, sponsored by Isabella and Ferdinand, the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus will discover the New World for Europe in 1492, claiming those rich and unspoiled territories for Spain. Naturally, what no one could expect when Christopher Columbus left for his expedition in search of an alternative way to the Indies, was the geographical impact his discovery would have, and its economic and political repercussions for Spain in the first place but also for the rest of Europe.

The year 1492 represents a symbolic date for the beginning of the imperial adventure of the case of Castile, with the end of the Moors' rule over the Iberian Peninsula – which ended the exhausting era of the reconquest wars – and with the agreement with Christopher Columbus for his proposed journey.

Nevertheless, in order to understand in which atmosphere the Hispano-American culture of the early Sixteenth century nurtured its roots, a look at the Spanish manifestations of intellectualism at the time of the conquest is necessary.

In light of the imperial pomp which developed in Spain during the sixteenth century, trying to visualize the cultural climate that preceded and in which the colonization of the New World was prepared could be misleading. The courtly environment of the Catholic Kings, still unaware of the American wealth, was, in essence, a simple environment, for which the adjective of "real" was used rather broadly. Isabella and Ferdinando did not, in practice, have a specific royal residence, but moved between castles and palaces to maintain and extend their control over the broad domains of their joint families.

The cultural project of the Catholic Kings, which was apparently carried out under the flagship of the Roman Catholic religion, was essentially driven by geopolitical aims and the necessity to create a common feeling in the newly established Kingdom of Spain. Catholicism as a common belief, and the Castilian as a shared and official language of the lands under the Kings’ rule, represent the unifying forces under which Isabel and Ferdinand create the cultural identity of pre-Renaissance Spain.

Historians recognize that Ferdinand, and mainly Isabella, were instrumental to the establishment in their courts of new forms of literacy and art in general, by means of a liberal patronage of writers, poets and musicians (not only Spanish but also coming from Italy, Catalonia, Aragon, Portugal), and also of literary visitors from Germany and Poland. The valet of Isabella, Juan Álvarez Gato (1433-1509), was a recognized poet of whom 104 compositions have been conserved.

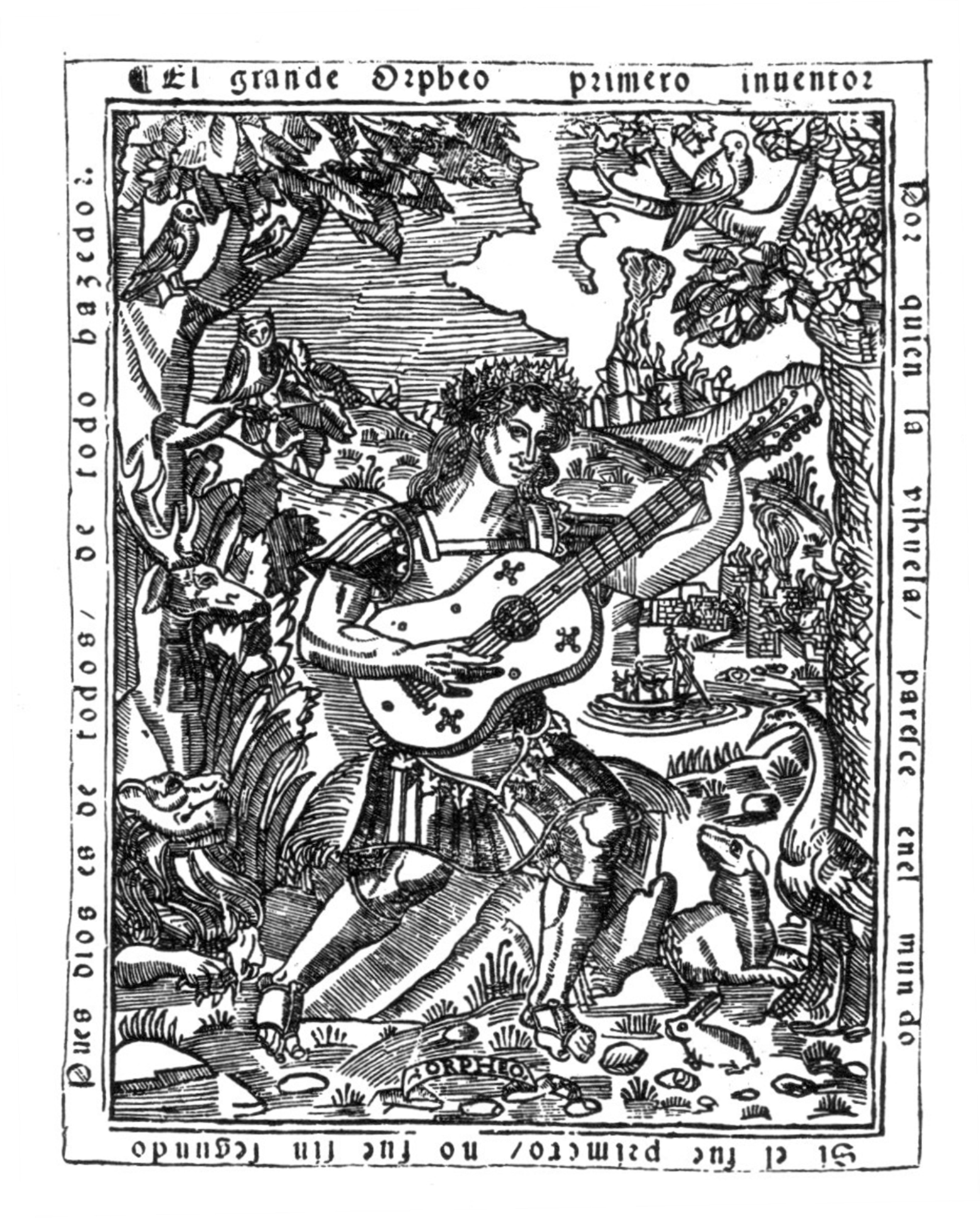

Also, in their concern for courtly music, the Kings supported a nationalist project, aimed at creating the bases for an autochthonous music. For centuries, before their ascent to the throne, it had been very common for kings to go and find singers for their musical chapels in Flanders, Germany and France. For Isabel and Fernando, however, it proved to be very important to build an exclusively national music chapel (Isabel had only cantores and chantres from Castile), aimed at encouraging the development of a "typical" Spanish music. Within this nationalistic approach, a place of honour certainly belongs to the vihuela, musical instrument among the favourites of the Catholic Kings. The oldest images of this instrument, which had as many names as there were places where it was played (viola de ma in Catalunya, viola da mano in Italy, viola de mão in Portugal), are found in the Cantigas de Santa Maria of Alfonso X of Castile, dating back to the 13th century. Unfortunately, there are no manuscripts of music for this instrument dating to the time of the Catholic Kings (the music press in Spain has never had great success, let alone with Spanish composers) but as early as 1536 Luys Milán (c. 1500 – c. 1561) gave to the press his work El Maestro, the earliest known publication of vihuela music, including a number of fantasias, pavans, and vihuela settings of Italian sonnets. In the next forty years, another nine printed books of music for vihuela were to be published.

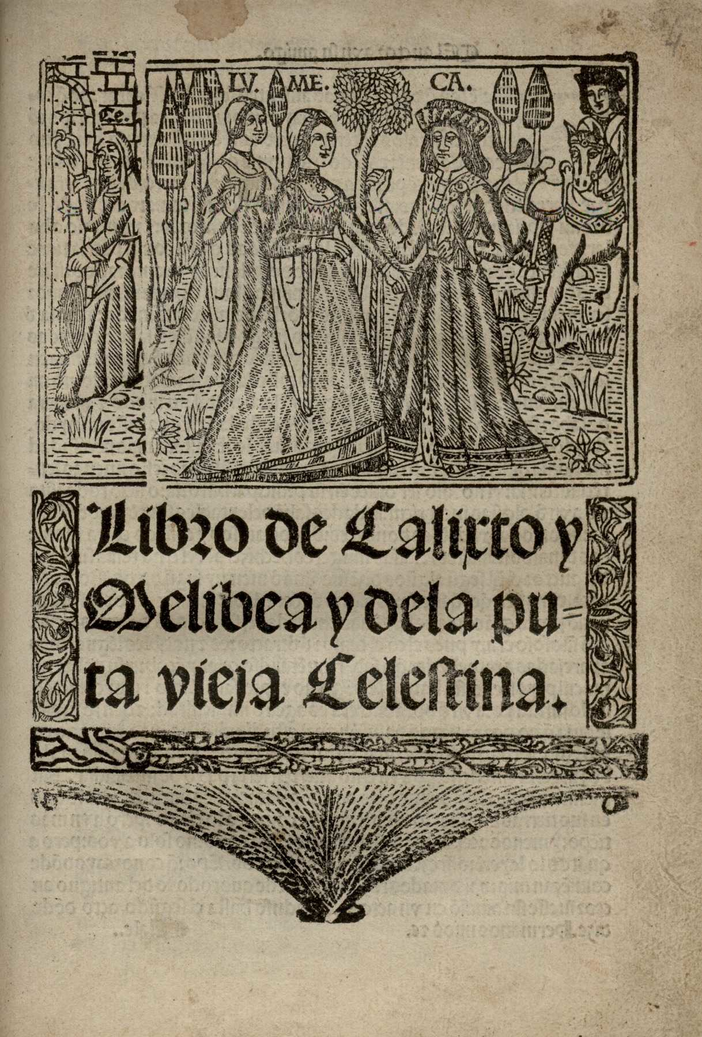

What is certainly true is that Spain under the rule of the Catholic Kings, as the rest of Europe, was beginning to make the slow transition from the medieval age, with the primacy of didactic style and strictly religious themes, to the courtly and renaissance age, with its celebration of courtly love and the triumph of theatre and profane poetry. It is not fortuitous that two key works of Spanish literature of those times, the Coplas by Jorge Manrique, and mainly the Celestina by Fernando de Rojas2 saw the light in the last decades of the century, and that the first grammar of modern European language, the Gramática Castellana (Castilian grammar) by Antonio Nebrija, dedicated to Isabella, was justly published in the febrile year of 1492. The court of Ferdinand and Isabel had its own poet in the figure of Pedro de Cartagena (1456–1486), of whom 88 compositions have been conserved, including canciones, villancicos, esparsas (monostrophic poems of troubadour descent), motes (mots), and several decires amatorios (love declarations), some of which of moral theme and other burlesque.3

Of course, Isabel's literary patronage is only explained as part of her attraction for all aspects of culture: from architecture to the plastic arts, from music to the celebration of religious and profane events, from her late commitment to learning Latin to her favor for the diffusion of the Castilian, that strived in speaking and writing with neatness. In the same field, we must place her obsession to elevate the cultural atmosphere of the court, supporting the establishment of outstanding humanists and favouring the creation of libraries; and the tenacity with which she insisted for her children to receive a careful education.4

Art patronage at the courts of Castile was extended to a number of painters, the most famous of which was probably the Master of the Virgin of the Catholic Monarchs, the author of the panel commissioned by the Kings, which portraits Ferdinand V and Isabel with their Saint patrons, the Infant Don Juan and the Chief Inquisitor.5 The Kings also sponsored the work of several foreign painters active in Spain, like Juan de Borgoña (1470–1536), native of the Duchy of Burgundy (before it ceased to exist as an independent state), whose earliest documented work was painted in 1495 for the cloister of the Cathedral of Toledo. He worked in Spain until his death in 1536 and is considered the author who brought into Castile the painting style of the Italian Quattrocento.

2 Whether the author was real or fictitious is outside the context of this study

3 Ana M. Rodado Ruiz, “La métrica cancioneril en la época de los Reyes Catolicos: la poesía de Pedro de Cartagena,” Ars Metrica, no. 5 (2012): pp. 1–24.

4 Nicasio Salvador Miguel, El mecenazgo literario de Isabel la Católica. In: F. Checa Cremades (comm.). Isabel la católica. La magnificencia de un reinado (Catálogo de la Exposición celebrada en Valladolid, Medina del Campo y Madrigal de las Altas Torres, febrero-junio de 2004). Salamanca, 2004, pp. 75-86.

––––––. La actividad literaria en la corte de Isabel la Católica. In: N. Salvador Miguel (comm.). Isabel la Católica. Los libros de la Reina (Catálogo de la Exposición celebrada en Burgos, diciembre de 2004-enero de 2005). Oviedo, 2004, pp. 171-196.

5 Due to the widespread influence of northern art in Castile, the extensive borrowings from the Masters of Netherlandish art do not necessarily lead us to suppose that he had lived outside Spain. For a long time attributed to Fernando Gallego (ca. 1440–1507), the altarpiece is assumed today to have been created by a follower of the Salamancan master, whose origins and nationality remain uncertain. Nevertheless, the high quality of the paintings attributed to the Master and the likely patronage of the Catholic Kings leave no doubts the fact that he was an important artist. Ferdinand and Isabel apparently commissioned also the retable “The Marriage at Cana”, where the prominent display of their heraldic devices and those of Maximilian I was probably meant to commemorate the marriage of their younger daughter, Juana of Castile, to Philip the Fair, Maximilian’s son (September 1496), and that of their son, Juan of Castile, to Margaret of Austria, Maximilian’s daughter (April 1497).

See J. Brown and R. G. Mann, Spanish Paintings of the Fifteenth through Nineteenth Centuries, The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue (Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 92-93.

Among the protection of the arts, it is necessary to also place the patronage dispensed by the Kings to music, as musicians had become indispensable in ceremonial and courtly spectacles, as well as in those cancioneril poems that were accompanied by music. Throughout her reign, Isabel was surrounded by a prominent body of atabaleros, trumpetists and minstrels; she considered music a form of regal propaganda and she worried, as per age-long tradition, about the musical education of his children, whose houses she endowed of numerous instrumentalists and composers who had the responsibility of rejoicing their moments of idleness and of educating them in the musical field. Just as an example, Prince John, at the young age of twelve, already counted with a musical chapel composed of 8 members.

After almost eight centuries of Muslim domination, and battles between Muslims and Christians, the siege of Granada (1481-1492), which ended with the capitulation of the last reduced Muslim of the Iberian Peninsula, was an event of the utmost importance, which opened the doors to the expulsion of the Moors in 1502/1503, assisted by the Holy Inquisition. As early as 1492, the Spanish Court of Inquisition had been responsible for the conversion or expulsion of the Jews from the peninsula, helping the crown of Aragon to see forgiven the numerous debts contracted by the King with Jewish bankers to marry his son with Isabella of Castile.

As for the "discovery" of America, that modern scholars interpret more accurately as an introduction of the Americas to Western Europe, we will discuss in the following chapters the profound impact it had not only in the geopolitical reorganization of the world but also in the concept that humanity had of its own planetary habitat.

To quote one of the greatest historians of Imperial Spain, «the conquest of Granada and the discovery of America represented both a beginning and an end».1 Whilst the successful entry into Granada marks the end of the reconquest of Spanish territory, it also inaugurates a new phase of the crusade against the Moors, with the Inquisition and the advances on African soil. On the other hand, the discovery of the New World marked the beginning of the Spaniard transoceanic colonization, while at home it ended the era of Castilian expansionism.

1 John H. Elliott, La Spagna imperiale: 1469-1716 (Bologna: il Mulino, 1982), p. 47.

All translation are my own except when mentioned otherwise.