Queer orientations

Ahmed suggests that “the stranger has a place by being ‘out of place’ at home” (Ahmed 2006, 141). As mentioned, the connecting costume crafted an experience of sharing a space, like sharing a temporal material-discursive home that was strangely out of place in the public environment. In some situations the costume was ‘a home’ that protected us from outside gazes and in other situations the costume was ‘a place’ that exposed us and showed that we were out of place. Thus, we had to navigate and negotiate how we could be at home in the costume, as a temporal home that was strangely (un)familiar. Internally the ‘costume home’ had defined borders or lines between us and the outside world, but the lines were not visible to the outside world.

Ahmed writes that “it is given that the straight world is already in place and the queer moments, where things come out of line, are fleeing” (Ahmed 2006, 106). Straightness as place-making orientations draw lines for how we expect that we must act in public. When we cross the straight lines of expectation, we potentially queer the moment and as such we appear as being out of line. Even though we might know that we are out of line, the queer moment might still be surprising, unexpected and out of our control. During the twelve hours we experienced many moments that somehow queered us and/or the situation. The queer moments were often evoked or provoked by outside responses or comments as well as how we, placed inside the costume, interpreted the outside responses or comments. For example, fleeting moments where by-passing people looked, stared, saw through, commented on, chit-chatted about, yelled towards or in other ways ignored or noticed us, affected us.

Ahmed continues that “queer orientations might be those that don’t line up, which by seeing the world ‘slantwise’ allows other objects to come into view” (Ahmed 2006, 107). As Ahmed suggests, queer orientation allows us to see outside of the lines and outside the norm. As such, walking in public while connected through a costume allowed us to view the world slantwise or from other perspectives than those of our daily lives. What came into view was that the costume acted as a queer object that orientated our orientations towards material and relational aspects of the costume. I write in the plural to indicate that our orientations were not always in line, as well as that we were not always affected in the same ways. In the queer moments we had to navigate and negotiate the relational encounters with the accidental guests or participants and/or the fleeing relationships that ‘popped up’ around us and that affected us. In other words, the costume orientated us towards human and more-than-human others what were placed outside the costume.

Towardness

Ahmed writes that towardness

is the fact that what I am orientated towards is “not me” that allows me to do this or to do that. The otherness of things is what allows me to do things “with” them. […] Rather that othering being simply a form of negation, it can also be described as a form of extension. The body extends its reach by taking in that which is “not” it, where the “not” involves the acquisition of new capacities and directions––becoming, in other words, “not” simply what I am “not” but what I can “have” and “do.” The “not me” is incorporated into the body, extending its reach. (Ahmed 2006, 115)

Ahmed argues that our orientation towards the otherness of things or objects enables us to do things with them. In the extension we do things that we ‘normally’ do not do, which expands our embodied capacities and (reach)abilities. The otherness – that the placement inside the connecting costume entailed – placed us in different positions that offered us a perspective other than what we have in our daily lives. The positions orientated us towards the otherness and queerness of the costume and of our material-discursive space, which allowed us to co-explore our bodies outside our normal or everyday realm of expectation. In the moments and/or situations where the costume acted as a queer object it enchanted us. Jane Bennett describes enchantment as a “state of wonder [where you] notice new colors, discern details previously ignored, hear extraordinary sounds, as familiar landscapes of sense sharpen and intensify” (Bennett 2001, 5). Thus, as queer object, the costume enchanted our sight of our everyday surroundings and made us encounter sides of the city that are out of our sights as sites for physical or embodied explorations in our daily lives. The enchanting moments or situations were sensations of being captured and captivated by a site and immersed with encountering the site. In these situations we expanded the (reach)abilities of our bodies. However, trajectories or boundaries between Bennett’s enchanting situations and Ahmed’s queering moments were fleeting. As such, in similar yet quite different ways the costume’s queering and enchanting qualities evoked, provoked and opened our sight to explore other or new sides, whereby we had new possibilities of gain new (in)sights. As such, Community Walk was not an either-or of being immersed or queer, but rather a both-and of immersion and queerness and flux between the otherness of perspectives of being positioned inside and outside of the costume.

It is evident that we with the costume and with the placement in public had multiple relational encounters in other or different ways than we have in our daily lives and that also differed from our performance and/or design practices. Placed inside the costume, our towardness allowed us to immerse ourselves in our explorations. In the immersed situation something or someone became visible and included, whereas others stayed out of our sight and were thus invisible and excluded. Placed inside the costumes, our towardness was therefore embodied explorations that included accidental participants and/or excluded them from encountering our material-discursive space. At the same time we could not prevent accidental participants from entering our shared material-discursive space.

In Tribes: Costume Performance and Social Interaction in the Heart of Prague Sofia Pantouvaki reflects on the PQ15 (1) project Tribes (2). Pantouvaki writes that as a costume “action-based event” Tribes had “both ‘informed’ and spontaneous spectators” (Pantouvaki 2027, 26). Situated in

the most touristic part of the heart of Prague […] photography – especially selfies – is a part of the daily landscape. This resulted in the medium of photography becoming a tool for social interaction with the costumed bodies. Therefore, taking photographs became a means for communication between viewer and object of the performance in the Tribes project. […] On the other hand, the photographic lens did not always result in positive feeling for the interaction in provoked. (Pantouvaki 2017, 33)

Even though we did not experience the accidental participants as “occasional spectators” (3) (Pantouvaki 2017, 34) who were orientated towards taking selfies, it also seemed like the photography, at times, entered and interfered with the ‘inside-spheres’ of the tribes. At the same time, and as an orientation, the photography enabled communication and/or exchanges between the costumed bodies, often fully masked, and the occasional spectators. Pantouvaki suggests that “the Tribes exhibition project showed that costume can have unlimited forms as well as an expanded potential for communicating ideas and experiences” (Pantouvaki 2017, 36). Pantouvaki suggest that placing costume encounters in public spaces expands our potentialities. During Community Walk we expanded our capacities and (reach)abilities in different ways and in different situations. Even in situations that made us feel vulnerable and exposed, within the safety of our shared material-discursive space we expanded our reflections towards speculation on how it might be to be vulnerable and exposed in public. How those placed outside of the costume tended towards our otherness affected and somehow expanded our capacities and (reach)abilities, but it remains uncertain whether the people placed outside in any way expanded their capacities and/or (reach)abilities.

Bibliography

References

Ahmed Sara (2010). Orientation matters, In (eds.) Coole D. & Frost S. (2010) New materialism – ontology, agency, and politics, Durham & London: Duke University Press. 234–257.

Ahmed, Sara (2006). Queer phenomenology – orientations, objects, others, Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Bennett, Jane (2001). The enchantment of modern life – attachments, crossings and ethics. Princeton University Press.

Hedemyr, Marika (2023). Mixed Reality in Public Space: Expanding compisition practice in choreography and interaction desing, Malmö University.

Hann, Rachel (2019). Beyond Scenography, Routledge.

Lindgren, Christina (2023). Christina Lindgren: Hedda Gabler, In (Eds) Lindgren, C. & Lotker, S., Costume agency – artistic research project, Oslo National Academy of the Art. 19–34.

Lindgren, Christina & Lotker, Sodja (2023). Costume agency – artistic research project, Oslo National Academy of the Art.

Lotker, Sodja (2023). Sodja Lotker: Devising Garment, In (Eds) Lindgren, C. & Lotker, S., Costume agency – artistic research project, Oslo National Academy of the Art. 35–46.

Lotker, Sodja (2017), The Tribes at the PQ 2015 — Introduction, (2017), In (eds.) Pantouvaki, Sofia & Lotker, Sodja, The Tribes – a walking exhibition, Arts and Theatre Institute. 6–15.

Lagerström, Cecilie (2019). Konsten att gå: Övninaer i uppmärksamt gående. Möklinta: Gidlund.

Marshall, Susan (2021). Insurbortinate Costume, Goldsmiths, University of London.

Pantouvaki (2017). Tribes: Costume Performance and Social Interaction in the Heart of Prague, In (eds.) Pantouvaki, Sofia & Lotker, Sodja, The Tribes – a walking exhibition, Arts and Theatre Institute. 25–39.

Skærbæk, Eva (2011). Navigating in the Landscape of Care: A Critical Reflection on Theory and Practise of Care and Ethics, Health Care Analysis, 19. 41–50.

Skånberg Dahlstedt, Ami (2022). Suriashi as Experimental Pilgrimage in Urban and Other Spaces. University of Roehampton.

Wenger, Etienne (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

Østergaard, Charlotte (2024). Performing Creative work in Public, In (Eds) Andersson, E.C.; Lindqvist, K.; Sandström , I. de Wit & Warkander, P., Creative Work: Conditions, Context and Practice, Routledge, 172–198.

Digital reference:

Alliances and Commonalities 2024

Additional readings:

Ahmed, Sara (2010) Happy Objects, in (eds.) Gregg M. & Seigworth G. J., The Affect Theory Reader, Duke University Press, 9–51.

Alenkær, Rasmus (2023), Pædagogisk værtskab og uro I skolen, Dafolo

Dean, Sally E. & Østergaard, Charlotte (2019). Traces of Tissues at PQ: Interweaving costume design, somatic choreography and site, The Society of British Theater Designers BLUE PAGES PUBLICATION 2019, 16-17.

Gelter, Hans (2013). Theoretical Reflection on the Concept of Hostmanship in the Light of Two Emerging Tourism Regions, In (eds) Garcia-Rosell, J.-C, Hakkarainen, M. Ilolas, H., Paloniemi, P. Tekoniemi- Selkälä, T., & Vähäkuopus, M., Interregional Tourism Cooperation: Experiences from the Barents. Articles Series “Public-Private Partnership in Barents Tourism (BART)”, Multidimensional Tourism Institute, Lapland University Consortium, Lapland Institute for Tourism and Education, Rovaniemi, Finland. 44–52.

Kenway, Jane & Fahey, Johannah (2009). Academic Mobility and Hospitality: The Good Host and the Good Guest, European Educational Research Journal, 8(4). 555–559.

Laloux, Frédéric (2014). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness. Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition.

Macnamara, Looby (2014). 7 ways to think differently – embrace potential, respond to life, discover abundance, Permanent Publication.

Medema, Monique & Zwaan, Brendade (2020). Exploring the concept of hostmanship through “50 cups of coffee”, Research in Hospitality Management, 10:1. 21-28.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (2005/1962). Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge.

Neimanis, Astrid (2023/2012). Hydrofeminism: eller, om at blive en krop af vand. Laboratoriet for Æstetik og Økologi.

O’Gorman, Kevin D. (2007). The hospitality phenomenon: philosophical enlightenment? International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1(3). 189–202.

Pellegrinelli, Carmen; Parolin, Laura Lucia & Castagna, Marina (2022). The Aesthetic Dimension of Care: Arts and the Pandemic, Organizational Aesthetics 11(1). 180-198.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (2003/1991). Situeret Læring – og andre tekster, (translated by Nake, B. from Situated learning. Legitimate Peripheral Participation published by the press syndicate of the University of Cambridge), København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Leah Lundquist, Leah; Sandfort, Jodi; Lopez, Cris; Odor, Marcela Sotela ; Seashore, Karen; Mein, Jen & Lowe, Myron (2013), Cultivating Change in the Academy: Practicing the Art of Hosting Conversations that Matter within the University of Minnesota, University of Minnesota.

Raymond, Christopher M.; Kaaronen, Roope; Giusti, Matteo; Linder, Noah & Barthe, Stephan (2012), Engaging with the pragmatics of relational thinking, leverage points and transformations – Reply to West et al., Ecosystems and people,17(1). 1–5.

Skærbæk, Eva (2002). Who Cares – ethical interactions and sexual difference. Højskolen I Østfold.

Telter, Elisabeth (2000). The philosophy if hospitableness, In (Eds.) I.C. Lashley & A. Morrison In the search for hospitality: Theoretical perspectives and debates, Routledge. 38–55.

Wenger, Etienne (1998). Communitis of practice: learning as a socialsystem, The systems Thinkers, 9(5). 1–5.

West, Simon; Haider, Jamila L.; Stålhammer Sanna & Woroniecki, Stephen (2020). A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations, Ecosystems and people, 16(1). 304–325.

Østergaard, Charlotte (2023). Community Walk, Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space – Catalogue. 304–305.

Note: some clips from this edit will also appear in videos within other pathways. These shorter video edits delve into specific topics explored within their respective pathways.

The material-discursive space

Sara Ahmed writes that “bodies as well as objects take shape through being orientated towards each other, an orientation that may be experienced as the cohabitation or sharing of space” (Ahmed 2010, 245). It was through the object – the connecting costume – that a shared material-discursive space emerged between us; a shared space that orientated us towards each other and towards exploring how we could co-inhabit the costume.

To summarise what I have unfolded in other paths, placed inside the costume the visuality of the costume provoked a heightened self-awareness and sense of exposure. At the same time the inward orientation created a relaxed and trustful atmosphere between us that sparked our willingness to explore the costume. Thus, the inward orientation orientated us towards our relationship and our connectedness or dependence. The twelve-hour walk fostered multiple encounters with human and more-than-human others that were placed outside the costume; encounters that threw us in multiple directions and that created sensations and experiences of, for example, exposure, vulnerability, curiosity, open-mindedness or playfulness. The sensations and experiences we had inside the costume were, at times, caused by the outside responses that included how we interpretated these outside responses. The interplay and/or counterplay between the inside and outside perspectives resulted in us constantly re-orientating ourselves and thus we had to navigate and negotiate between our inward experiences and the outward expressions.

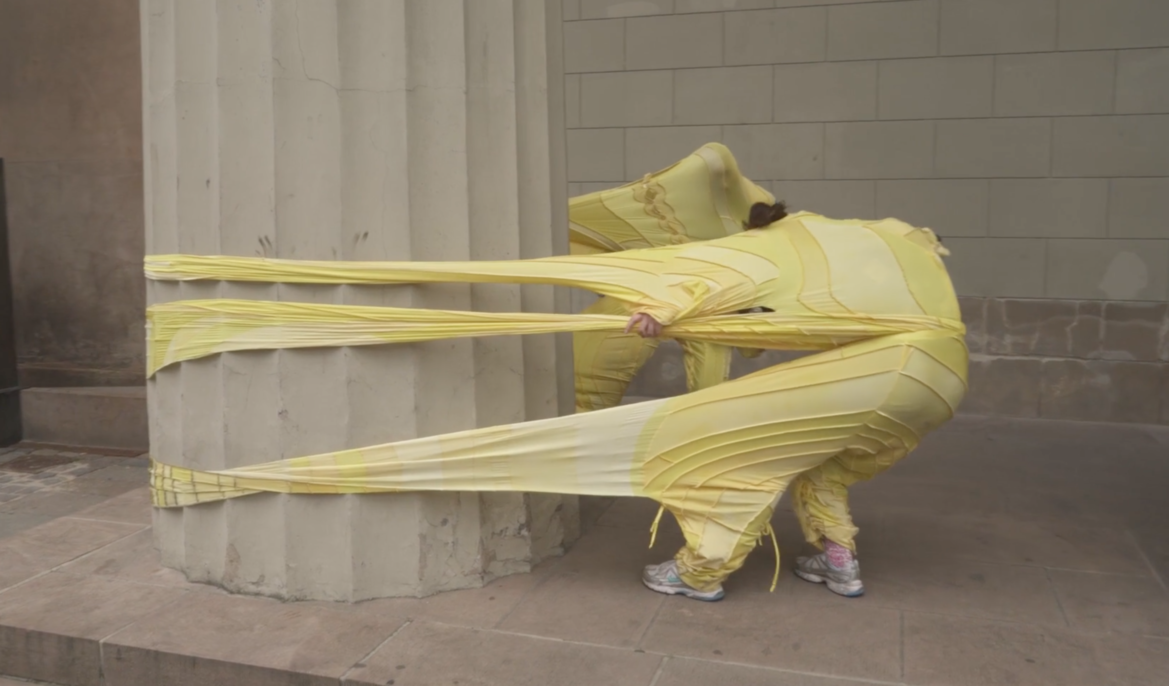

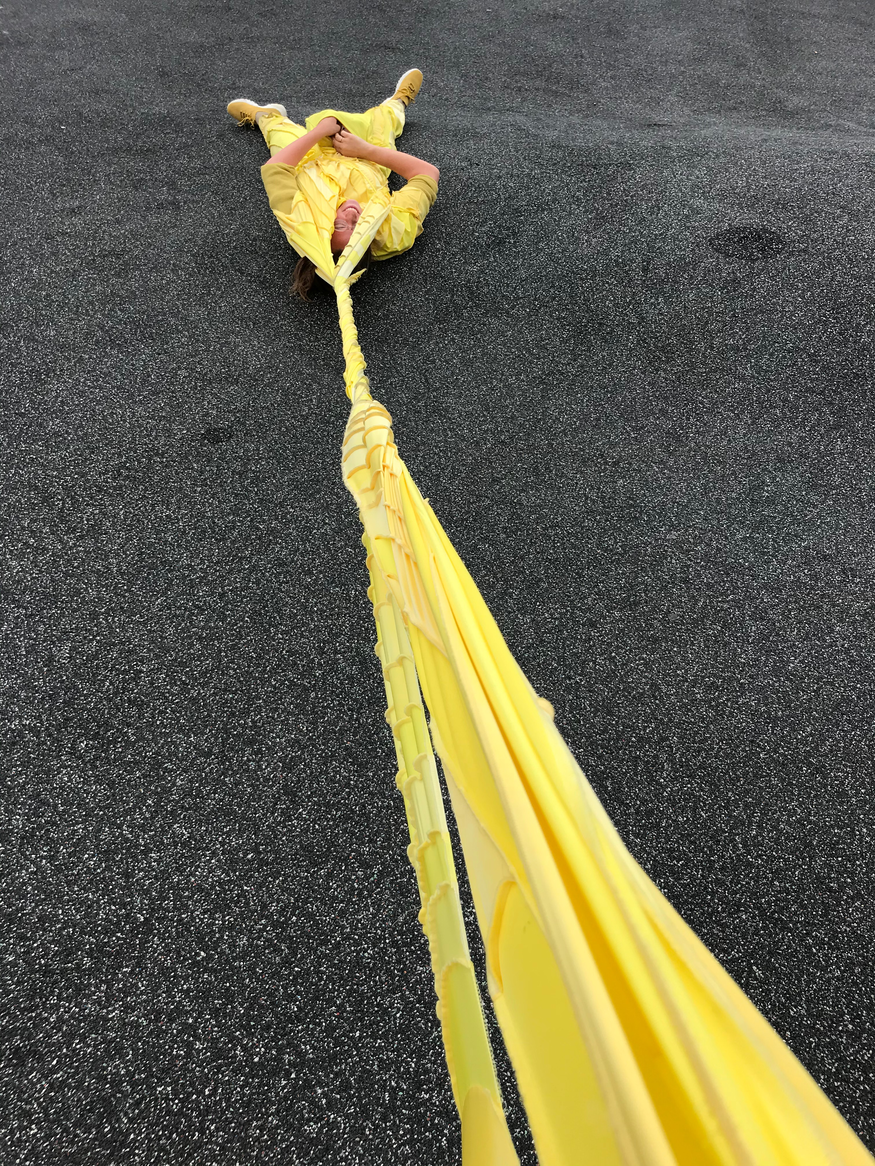

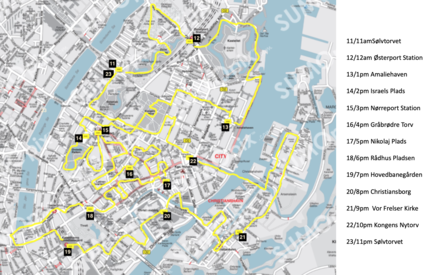

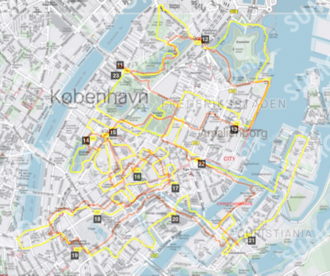

In the artistic project Community Walk (2020), that was part of the Metropolis festival Wa(l)king Copenhagen, I walked for twelve hours (11:00–23:00) in the central area of Copenhagen (Denmark) dressed in a bright yellow costume that connected me to twelve different guests, one at a time. The invited guests were designers, performers, choreographers and visual artists, and I walked with each guest for one hour. As series of connected pairs, we navigated and negotiated with the costume in the unpredictability of the public space.

In this artistic project I use Sara Ahmed’s concept of “orientation” to explore how crafting is an orientation towards something specific and how the costume during Community Walk fostered bodily orientations that threw us in different directions. Additionally, with Ahmed’s orientation I approach what hosting with communal hospitality implies. For example, by exploring how I navigated between being a curious participant and being the responsible host.

The participating guests were Agnes Saaby Thomsen, Aleksandra Lewon, Anna Stamp, Benjamin Skop, Camille Marchadour, Daniel Jeremiah Persson, Jeppe Worning, Josefine Ibsen, Julienne Doko, Lars Gade, Paul James Rooney and Tanya Rydell Montan.

Video edit of the twelve hour Community Walk

This 36-minute video is a condensed version of the twelve-hour Community Walk, showcasing all twelve participants. It features a variety of locations we explored and captures some of our encounters with both humans and more-than-humans. The video perspective shifts with the final participant, as I held the camera while walking.

Videographer: Benjamin Skop. Videoediting: Charlotte Østergaard.

Participants (in alphabetical order): Agnes Saaby Thomsen, Aleksandra Lewon, Anna Stamp, Benjamin Skop, Camille Marchadour, Daniel Jeremiah Persson, Jeppe Worning, Josefine Ibsen, Julienne Doko, Lars Gade, Paul James Rooney and Tanya Rydell Montan.

(1) The 13th Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space (The Czech Republic), June 18–28, 2015.

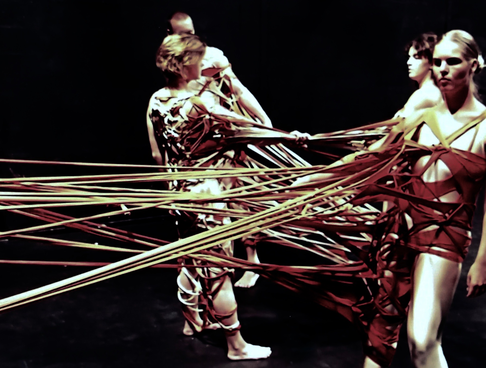

(2) Tribes – a walking costume exhibition – was curated by dramaturge and artistic director of the Prague Quadrennial Sodja Lotker. Lotker writes that “the core idea was to use the city – Prague – as a gallery/exhibition space and costumed living people as exhibited artefacts, as an experimental exhibition, a play on what makes an exhibition of performance design” (Lotker 2017, 7). There was an open call to contribute to and participate in Tribes that, as Pantouvaki describes, ‘‘invited a minimum of 4 people” that “are fully masked” and “have a dress code” (costumes of similar aesthetics) as well as “a behavior code (unified was of acting)” (Pantouvaki 2017, 27). During PQ15 “83 tribe walks happened/took place during the 11 days. Some days there were only 6 walks, some days there were over 20” (Lotker 2017, 10). It should be noted that all 83 tribes followed a pre-planned walking route devised by the PQ15 team.

(3) Pantouvaki notes that the audience “consisted of both ‘informed’ and spontaneous spectators” (Pantouvaki 2017, 26). Pantouvaki continues that “the audience that happened to be present at a specific place in a given moment of a day in which a tribe would pass by would become occasional spectators; these individuals became audience members because of the momentum. […] [T]he spectators’ bodies were engaged in experiences of the Tribes through their own movement. […] [E]very spectator had the opportunity to watch as much of the performance as they wished” (Pantouvaki 2017, 34).

Orientation(s)

In this path I unfold how Sara Ahmed’s concept of “orientation” informs the artistic project Community Walk. For example, that positions or placements are our starting points and that my hosting orientation framed and informed our explorations with the costume. Before I do so, I would like to share that hosting stems from a genuine wish to share experiences with other people and from an urge to explore relational aspects of costume, such as exploring what happens when we are connected with a costume and thus share a material-discursive space.

Positions as starting points

In Queer Phenomenology – orientation, objects, others Sara Ahmed writes that to be orientated depends on taking points of view as given (Ahmed 2006, 14). Thus, our orientation towards things or objects – whether they are human or more-than-human – depends on the view we have from our placement or position. For instance, what we see, take for granted, assume and/or expect informs our viewpoint or orientation. Ahmed continues that

orientations are about how we begin: how we proceed from “here,” which affects how what is “there” appears, how it presents itself. In other words, we encounter “things” as coming from different sides, as well as having different sides. (Ahmed 2006, 8)

Ahmed suggests that how things appear to us depends on the view we have from our position. As we encounter things how things appear are our starting point. For example, how a costume appear to us affects what we expect or assume that the costume will enable us to do.

In collaborations the challenge is that as we arrive to collaborate, we will most likely not see, expect and assume the same. For example, in Community Walk we encountered the connecting costume, our expectations and assumptions regarding what the costume would enable us to do was most likely different. I had crafted the costume and the guests had only images – that I had e-mailed them – and as such our (in)sights to the material qualities of connecting costume were different. Thus, our starting points, or orientations towards the connecting costume, were different. In other words, our point of departure was informed by the (in)sights or overview we had of the costume.

Ahmed’s use of the word side suggests that there are sides that are invisible or unknow to us and thus our sight is always partial. Thus, whoever we are – the participant performers or the participating host – as we arrived there are sides of the costume and/or of the event that we had no sight of and that was unknown to us.

The participating host

As mentioned (in Crafting Orientations), my ambition with Community Walk was to challenge myself by wearing a costume that was not too comfortable for me and exploring the costume in a public environment. However, not only did I place myself in a situation that was challenging to me, but I also invited participants to join me in this unfamiliar setting or situation.

Sara Ahmed writes that

in a familiar room we have already extended ourselves. […] If we are in a strange room, one whose contours are not part of our memory map, the situation is not easy. […] [T]he work of inhabiting space involves a dynamic negotiation between what is familiar and unfamiliar. (Ahmed 2006, 7)

Ahmed points out that in familiar rooms or situations we have already extended ourselves and thus we are more at ease in our bodies than we are in those situations that are unfamiliar to us. In unfamiliar spaces and situations we cannot necessarily draw on our embodied map and we must thus navigate and negotiate how we inhabit the space. In Community Walk we had to inhabit the costume and the shared material-discursive space through dynamic negotiations of what was familiar and unfamiliar to us, individually and collectively. As host I had to navigate familiarities and unfamiliarities of the costume, the participants, our shared space and the public surroundings, and negotiate the creativities that the situations evoked between us. As series of connected pairs we had to navigate and negotiate the potential unpredictabilities that occurred in the situations.

As participating host my ambition was to explore who we became, how we acted and/or negotiated as creative partners in public and how the public environment orientated and affected our creative doings.

Participating and hosting

Even though it was an active choice, I did not reflect upon whether it was a good idea to place myself at the centre. I did not question whether I was able to host and participate simultaneously or what this double role required of me. I had no prior experience of walking in a costume for twelve hours and I did not know what to expect, for example what the event would provoke and/or evoke in me, in the participants, in us as series of connected pairs and/or in those people that we would meet or pass. Still, the duration of the event was quite different than I had imagined. I had expected moments of exhaustion. Instead, I experienced that my energy was constantly amplified by the arrival of new participants. Each time I had to be attentive, tune and re-attune myself to the participant that just arrived, and I was genuinely curious to explore which (new) perspectives and creative suggestions this person had to offer. During the twelve hours I was engaging with the twelve participants and my energy or focus was more directed towards them than towards myself. Consequently, I forgot daily actions like eating, drinking, and even going to the toilet.

Even though I knew all twelve participants, with each participant I arrived at a new encounter, and they arrived at the encounter with me. As a pair we arrived at the beginning of our ‘walking and talking’ journey, where we opened creative ‘doors’, however in each of the twelve walks we never opened the exact same ‘doors’ as we did in the previous walks. Thus, even though I had created a structure that I repeated with all twelve participants, the twelve journeys or walks were not just a repetition.

As we constantly moved or walked through different areas of central Copenhagen, new surroundings, new surfaces and structures, new nature/urban elements, new by-passing people and may other ‘things’ were temporarily present as potentialities or as sites for explorations. During the twelve hours the city showed different sides of itself, from noisy streets with busy commuters to silent parks with soundscapes of birds, from streets with no people to pedestrian streets packed with people, from streets where people socialized at cafés in relaxed manners to streets with hectic night life. During the twelve hours we walked under the sun, under greyish clouds and under the moon and the stars. At places I sensed the touch of the wind, but I always sensed the presence of the participating partner that I was connected to.

With each participant I explored how I related to them, how we related to each other, how my invitations could create a trustful and playful atmosphere between us and how the framing framed us. As host I invited the participants to become co-creators who could initiate and host actions and/or explorations that interested them.

Ritual transformations

As the consistent participant I experienced that some rituals transformed, particularly the transition ritual changed during the day (Østergaard 2024, 183). In the first couple of transition situations I experienced some awkwardness or uncertainty between the arriving and the departing participant in terms of how to handle and hand over the costume. The awkwardness transferred to me as a sense of insecurity of how I should act or perhaps it was the other way around? In costume fitting situations I always, in a careful and respectful manners, offer my assistance and if requested I accommodate the dressing. Being placed inside the costume I was unable to offer the same kind of assistance. Moreover, placing the transition situation in public, they were not comparable to fitting situations. Still, the situation reminded me of how I act in costume fitting situations, and it was uncomfortable and felt somewhat unethical that I, the host, did not know how to act or whether I acted in an adequate manner (Ibid). At the same time, I did not want to direct or dictate how the transition should be performed.

As such, the transition ritual departed from the caretaking that I normally undertake in fitting situations, implying that I had specific expectations towards myself – expectations that I was unable to fulfil. Over time the ritual transformed from a somewhat awkward situation to become a relational ritual between the departing and arriving participant, where one helped the other to get dressed in the costume. It became an act of care – that happened between participants, several of whom did not know one another prior to the act – and a generous invitation from the departing to the arriving participant to step into their part of the costume and to continue the walking exploration. Witnessing the transformation of this ritual was touching.

Durational placements

Ahmed writes that “orientations shapes what bodies do, whiles bodies are shaped by orientations they already have” (Ahmed 2006, 58). As we arrive, we have an orientation that will shape what we can or will do. In Community Walk we did not arrive with the same orientation and thus we did not proceed from the same here. The fact that I placed myself in the centre (walked for twelve hours) and the participants were placed as visiting guests (walked for one hour) meant that we did not enter the costume at the same time and the duration of our participation in were different. Therefore, as a new guest arrived our orientation towards the costume as a material-discursive space were different. A few of the participating guests had been part of the artistic project AweAre–- a movement quintet, but most of the participants only had images to guide their interpretations of what the connecting costume enabled us to do. My intention was to explore whether there was any difference between having some knowledge of wearing a connecting costume and ‘jumping in’ rather unprepared and spontaneously. As it turned out, the unpredictability of the public affected and orientated the experiences of the costume in ways quite different than placing the exploration in the safety of a rehearsal space. Thus, there were not noticeable differences between the participants that had worn other versions of connecting costume and those that had not.

Ahmed writes that to

turn towards objects within phenomenology […] is not about the characteristics of such objects, which we can define in terms of type, the kind of objects they are, or their functions, which names not only the “tendency” of the objects, what they do, but also, what they allow us to do. (Ahmed 2006, 33)

In this extract Ahmed suggests that objects in a phenomenological sense are not about their characteristics or functionalities but about what they allow us to do. Still, to turn towards phenomenology is to experience what the specificities of costume – for example its materialities and compositional properties – do to our bodies and what these properties allow us to do.

In Beyond Costume Rachel Hann (1) writes that

both the experience of dressing within costume and interpreting its semantic overtones, offer a means of positioning costume as a mode of place orientation where costume affect performers as part of a reciprocal conditioning between body and fabric. (Hann 2019, 48)

Hann points to what costume communicates and how costume affects performers bodies. Moreover, Hann suggest that “costume choreographs action, while the choreography activates costume” (Hann 2019, 48). This can be interpreted as stating that costume is a device that enables designers, performers and other performance-makers to develop choreographies or embodied dramaturgies. In line with Hann, in Costume Agency – artistic research project (2) costume designer Christina Lindgren and dramaturg Sodja Lotker suggest that in costume performance-making processes of performativity come from the material (3) (Lotker 2023, 35), including that costume is a tool to discover new sides of characters (4) and new concepts for the interpretation of dramatic texts (Lindgren 2023, 28). As such Lindgren and Lotker argue that costume allows us to generate performances.

In the context of Community Walk my former experiences with other connecting costumes gave me knowledge of the bi-stretch textile materials in combination with the spatial composition had stretching and bouncing tendencies that potentially made us playful. Susan Marshall (5) suggests that being playful with costume is to be “mentally flexible, spontaneous, curious and persistent” (Marshall 2021, 63–64). I suggest that when we are spontaneous, we are flexible, instinctive and intuitive in our responses, and when being curious our attitude is perhaps a bit more persistent, analytical and/or reflective. In Marshall’s case the costumes are modular, and the playfulness explored some of the very many different possible ways in which the modules could be combined and worn primarily by one person. The knowledge I gained from other connecting costume versions was that playfulness meant being curious towards how the stretching (com)positions orientated and affected us bodily and collectively. It is also about being willing to spontaneously bounce with the materialities and with the wearing partner(s), as a game of bouncing and navigating together. Thus, I expected that our explorations with the connecting costume in Community Walk would be playful.

However, I had no experience of wearing and exploring a connecting costume in an urban setting. I did not know how such a placement and the duration of twelve hours would affect me physically. Moreover, situated or placed in a public environment implied that I could not predict or control what would happen. The question was how I could partake and at the same time host a situation that was unknown to me, and that to some extent was uncontrollable. How could I create conditions that orientated us towards attending and exploring what the costume allowed us to do?

Hosting orientations

My intention in Community Walk was to place the twelve participating guests and myself as horizontally as possible in the costume. Ahmed writes that

spaces too are orientated in the sense that certain bodies are “in place” in this or that place. […] Orientations affect how subjects and objects materialize or come to take shape in the way that they do. (Ahmed 2010, 235)

In the context of hosting, even though we most likely arrived with different orientations, I suggest that the costume as material-discursive spaces are orientated by how hosts host. For example, the host’s invitation indicates to the guests what they are invited to do and how they are expected to act to be in place. In the situation the attitude of the host indicates whether the guests are in place, out of place or whether the placemaking is a negotiable and shared explorative matter. As such, the host’s invitation frames the place or space, and the host’s attitude will orientate and affect what the guests and the host are able to do together as well as how the space materializes.

Invitations can open, provoke, inspire, excite, confuse, limit or in other ways orientate guests’ interpretations, assumptions or imaginations of what being in place implies. Even though the host has framed the situation, the host cannot assume, expect or know how the invitation will orientate guests. The guests arrive with their partial sight of the site that is partially informed by the host’s invitation, and that is most likely also partially informed by the guests’ former experiences of situations that might be alike. Still, an invitation will orientate how the guest and the host – individually and collectively – enter situations or events. As they arrive their orientations will affect how they can proceed and progress. In other words, an invitation will orientate the orientations we have as we arrive. As we proceed, our orientations will affect how we attune and/or (re)orientate ourselves towards each other, towards the connecting costume as the material-discursive space that we will share and explore together. Moreover, our orientations – as our starting points – affect how humans or more-than-human others materialise themselves to us.

As an attempt to create a shared space or starting point for Community Walk, I crafted the connecting costume and five rituals (described in Starting points and framings) to frame the event. The framing was a crucial part of my invitation and through the initiation the guests were informed about the conditions of their participation. As they arrived their orientation might, or might not, have been informed by my invitation. I write might since it is reasonable to suggest that the guests’ orientation was also shaped by, for example, experiences and/or encounters that happened five minutes or five years prior to their arrival. No matter what kind of orientations the guest arrived with, it still mattered how I invited the guests into the costume as well as how I hosted the situation, since the hosting attitude informs what the guests are able to do.

As mentioned, my ambition was to create a horizontal relationship between us. As a host with good intentions, how could I guide and direct my guests to enter the costume and the material-discursive space? Ahmed notes that “within the concept of direction is a concept of ‘straightness’. To follow a line might be a way of becoming straight, by not deviating at any point” (Ahmed 2006, 16). ‘Straightness’ implies that the host has articulated and/or unarticulated expectations towards the guest, such as expectations regarding how the guest must be in line or place and/or what kind of actions are considered as stepping in or out of line. The framing or the hosting encompasses rules, values, cultures, expectations and directions to guide the guests that indicates how the event is expected to proceed. ‘Straightness’ as a hosting attitude or strategy is therefore not just a guideline but is a direction to ensure that guests stay in line. ‘Straightness’ as the hosting strategy or hosting orientation potentially controls, limits and imprisons guests in the realm of expectations. On the other hand, if ‘straightness’ is used as a critical tool towards the hosting intentions, it asks the host to consider how strict the directions are and whether the host is willing to re-orientate the hosting directions and thus (re)negotiate and re-orientate the hosting attitude. Therefore, not only in the preparation of, but also during an event like Community Walk, the host must be critical towards the ‘straightness’ of hosting intentions to discover which expectations and assumptions might be ‘hidden’ in the directions, invitations, framings and/or attitudes.

(1) Rachel Hann (PhD) is a cultural scenographer and current AHRC Fellow based at Northumbria University, Newcastle (UK). She researches more-than-human cultures of performance design, climate crisis and trans performance.

(2) The Costume Agency project (2018–2022) explored “how costume performs” (Lindgren & Lotker 2023, 13). The project was initiated and facilitated by costume designer Christina Lindgren and dramaturge Sodja Lotker (PhD) and was supported by Norwegian Artistic Research Program and Oslo National Academy of the Arts. In the eight workshops multiple costume designers (professionals and students) and performers were invited to join and contribute to the research.

(3) In workshop #2 Lindgren & Lotker explored costume and materials though devising methods.

(4) In workshop #1 Lindgren & Locker worked with act 4, scene 4 of Henrik Ibsen’s drama Hedda Gabler (Lindgren 2023, 20). By repeating the scene, they (the researchers and actors) explored how changing Hedda Gabler’s costume (six different versions) affected the character (and actor playing Hedda Gabler) and the three other characters/actors in the scene.

(5) In the thesis Insubordinate Costume costume designer Susan Marshall (PhD) explores how performers and designers become inventive and playful with her modular costumes.

Crafting Orientations

Craft as orientations

Sara Ahmed writes that “to be oriented in a certain way is how certain things come to be significant, come to be objects for me” (Ahmed 2010, 235). Ahmed suggests that our orientation determines whether we notice things that are nearby or that surround us. Orientation is the way that our attitude and attunement are directed and how certain things materialise and become a bodily presence to us. Thus, in crafting processes we must attend to our orientation.

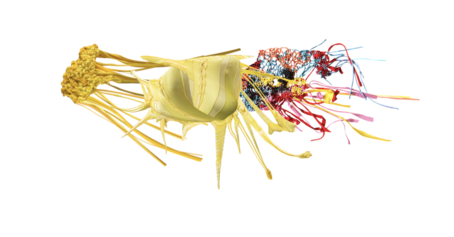

Like Ahmed’s object, textile materialities become significant to me when I craft. Crafting orients me towards sensorial experiences and compositional potentialities of specific textile materials. The sensorial experiences of specific textiles orientate me towards my body, which might be implicit. On the other hand, these orientations that bounce back and forth between the textiles and my body are essential. This bouncing awakens my sensorial orientations and sparks an urge to collaborate or co-create with the textiles. As a gift, the textile materials spark my imagination. Sparked by the bouncing orientations, I imagine outlines of costumes: for example aesthetic and visual expressions, functionalities and assumptions of sensorial experiences. The way that I am orientated in a specific situation affects how I envision a costume and how I will craft a costume. For example, while crafting the AweAre costume (link) my ambition was to make kin with the textile materials. I was orientated towards listening with the textile materials, aiming to spark a dialogue with and between them and the crafting techniques. I was orientated towards a metaphorical and imaginative dialogue with the textiles on how to craft or shape the AweAre costume.

Ahmed notes that “the things we are orientated towards is what we face, or what is available to us within our field of vision” (Ahmed 2006, 115). For example, the way that I face textiles and crafting will orientate how I envision a costume and/or the things that are available in the situation, which will orient how I can and will craft a costume. Things include, for example, material, compositional and functional considerations. The things that are available are always contextual and situational. In Community Walk some of the things or considerations were the duration and spatial elements that were entailed in the invitation to participate in, and contribute to, the Wa(l)king Copenhagen festival. As I will unfold below, the festival context orientated me towards crafting a connecting costume that I would wear and share with twelve different guests in the urban landscape.

Wa(l)king Copenhagen – the festival context

The Wa(l)king Copenhagen festival was developed by Metropolis (1) as a response to the Danish Covid-19 lockdown. Metropolis invited 100 different artists to over 100 days (starting 1 May 2020) to artistically (a)wake or (re)activate an area, chosen by the invited artists, in central Copenhagen for twelve hours. I was invited on 7 July 2020 – Community Walk was on 30 July 2020 – which offered little time to plan and organise my contribution. However, the awareness of the fact that I was the only costume designer who was invited to participate in the festival, immediately orientated me towards envisioning a connecting costume creating a material-discursive space between two people in the public environment. Due to the personal nature of the invitation I pictured myself as being ‘in the centre’, and that twelve different guests would join the walking-exploration with the costume for one hour each. As opposed to the artistic project AweAre – a movement quintet, I was orientated towards wearing and experiencing the bodily effects of being connected and of sharing a material-discursive space for twelve hours with twelve different people.

Crafting the connecting costume for Community Walk

The connecting costume that I envisioned was recognisable in its idiom and was crafted in flexible or stretchable textiles. My ambition was that the costume should depict clothing that was so common that it somehow disappeared in the public environment and that it was as visible and/or readable as a traffic light. The immediate impulse was to craft the costume in bright yellow, but since the AweAre costume also was crafted in yellow nuances I searched for textiles in bright reds, greens and blues. However, I kept returning to the bright yellow bi-stetch materials that I had in stock.

I did not want the costume design to represent or repeat more classical aesthetic choices or designs of mine, such as resembling the AweAre costume or other connecting costume versions that I had crafted prior (2). As mentioned, my intention was to explore the costume from ‘inside’ and, at the same time, I did not want the costume to be too comfortable for me to wear in the sense that it reproduced clothing that I have in my wardrobe and that I wear in my daily life.

I imagined that the costume should resemble relaxed sportswear like track suits, not too tight or bodily revealing, the kind of casual clothing that many people of different ages wear in their daily life in public: not fashionable and not pointing towards specific sports activities.

The connecting ‘track suit’ costume that I envisioned consists of two visually similar jumpsuits that were connected at three points: arm, torso and leg. I wanted the jumpsuits to be functional and flexible in the sense that it would be easy to enter or jump into, that the size enabled the participants to wear the costume over their own clothing and that the fit was easy to adjust to the measures of the twelve participants. As it may or may not appear, the costume that I imagined orientated me towards quite specific visual, functional and material aspects. In principle, I could have made a sketch or a technical drawing and hired someone to produce the costume. I did not. Instead, I made a prototype of the jumpsuit to test how to make an adjustable size, to test the placement of the three connecting points and to test other functionalities, such as the length of the opening and the number of buttons, including testing size-adjusting mechanisms to tighten the waistline and make the pants/legs shorter. With these functionalities in place the costume could have been easy and quick to craft. However, I had far from enough yellow bi-stretch material in stock to make two similar jumpsuits. There was no time to order additional bi-stretch textile from any supplier and no fabric stores in Copenhagen had any bright yellow bi-stretch. Thus, I decided to dye whatever whiteish bi-stretch textile I had in stock. Due to the fibre combinations of the textiles the dying of the different fabrics turned out as a pallet of yellow nuances. From the textile pallet I created or sewed a yellow-collage piece of fabric. With some fiddling, there was just enough fabric to sew two jumpsuits. The leftover pieces of fabric I sewed together, and the length of the sampled pieces decided the length of the connecting parts of the costume. In the end the two jumpsuits appeared visually alike, but they were not as similar as I had imagined. However, I was pleased with the collage-pattern look: the collage-look referred to track suits but did not look too much like mass-produced clothing. The limitations of the bi-stretch available in the situation, meant that the ‘track suit’ connecting costume version had a visuality of its own – a look that I could not or did not envision prior to crafting the costume.

Walking with costume

As mentioned, the festival Wa(l)king Copenhagen was a response to the Covid-19 pandemic: it was an artistic invitation to (re)wake the city by walking. In Konsten att gå (The Art of Walking) artistic researcher Cecilia Lagerström writes that there is a growing number of artists who use walking as a central theme in their artistic practice (1) (Lagerström 2019). The growing interest in walking was, for example, very visible at Alliances and Commonalities 2024 (2) where the conference conveners – due to the fact that many proposals centred around walking – decided to create an additional stand “on walks, and walking.” It can be argued that research on walking as, for example, an artistic expression or shared experiences or events is more visible as a ‘trend’ in dance, choreography and site-specific performance contexts (3) than it is in costume practice and/or costume research. However, the PQ15 project Tribe (4) (further unfolded in The material-discursive space) shows that walking dressed in costume in a public space contributes other or new aspects to walking and costume discourses. Sofia Pantouvaki writes that “without the text, Tribes succeeded in proving the performative as well as the narrative and communicative potential of costume thorough the language of the body as a result of embodied experience and everyday life encounters” (Pantuouvaki 2017, 36). Moreover, as an exhibition project “Tribes invited costume to escape the boundaries of the conventional exhibition space in order to be more communicative in direct connection with the public” (Pantouvaki 2017, 37). Pantouvaki suggests that placing costume in events like Tribes in public spaces positions costume in other ways than in theatre or exhibition contexts that enables, for example, costume to escape the boundaries of (dramatic) text and/or static exhibition displays.

It can be argued that by the naming the artistic project Community Walk I missed the opportunity to highlight that costume was paramount. On the other hand, walking became the medium to encounter and approach costume from the perspective of hosting and participating in communal (5) acts. The costume became a technical device that connected me to twelve different artists and walking in public became the technique that orientated me towards exploring how I could act as a responsible host during the communal acts. Placing the event in public amplified the view that being accountable for the event I sat in motion do not imply that I can predict or control what will happen during the event. Still, as the host I was responsible for how I responded to the unpredictability and uncontrollability that the public environment. For example, when by-passing people approached us or commented our appearance, I did not expect my fellows to respond, however, I was responsible for how I responded. By responding curiously but not too inviting, for example with a smile, and sometime just ignoring the by-passing people’s comments I politely excluded them from getting too close. Even though some people became accidental participants, they remained positioned as by-passers and as by-passers they affected our common doings, for example re-orientated our dialogues or our physical explorations. I suggest that how I responded to the unpredictability and uncontrollability of the public orientated our orientations, or rather with my responses I acknowledge the unpredictability and uncontrollability of the public while at the same time I indicated that I was orientated towards the material-discursive space that I shared with the fellow artists.

I had invited the fellow artists to join me since I was curious to explore how the costume and the event would spark their creativities. As host I was responsible for creating conditions that enabled the fellow artists to respond to the costume and the event and, importantly, I had to repeat my invitations. As it turned out the costume and the event sparked the fellow artists’ creativities in multiple and often surprising ways. As co-creators they invited other people and more-than-human elements to momentarily entangle with us and the costume – these entangled moments became part of our common doings and was a share act of communal hospitality towards human and more-than-human others. Thus, as host I had to host with hospitality towards the communal doings of the twelve co-creators that with their creative orientations offered perspectives that were different to mine. With their creative orientations the co-creators expanded our common doings and our communal costume doings with and towards human and more-than-human others. As such, Community Walk taught me that I as host must be hospital towards what we share by being willing to re-orientate my creative doings in order to open a space where our creativities can flourish together. I am accountable; I must be willing to re-orientate my creative expectations and thus let go of creative control.

I finished crafting the costume a few days before the event, which potentially offered me time to rehearse in the costume. However, placing myself ‘in the centre’ was an ambition to challenge myself to explore a connecting costume on new and other terms and/or perspectives than I had done prior (3). Another intention was to place the twelve participating guests and myself as equally or horizontally as possible in the material-discursive space. Thus, I did not rehearse any walking in public prior to the event, in the hope of enabling a more spontaneous and intuitive walk.

The spatial orientations of crafting

Previously I suggested that crafting is a matter of the crafter’s orientation and thus crafts and design people must attend to our orientation. I unfolded that the Metropolis invitation orientated me towards crafting a connecting costume and towards placing myself in an unfamiliar situation. The crafting process or strategy that I described is perhaps in line with more classical design processes where a costume design concept is informed by the performance context. However, crafting costume involves more than the conceptual framework of the design/performance and more-than-textiles.

Ahmed’s orientation starts at the writing table with tools like a pen and paper, which are aspects that enable her to write. Like writing, crafting is an activity that orientates the crafter towards things that enable the labour of crafting. The video highlights and values the spatial conditions and the tools that enabled me to craft the costume for Community Walk.

Video (3:31): The choreography of crafting.

A video in four ‘acts’ with the things that enable crafting:

The pattern making: paper, scissors, ruler, pencil.

The dying of fabric: dye, pot, water, spoon, stove, electricity.

The cutting of fabric: scissors, patterns, needles.

The sewing the costume: machines, scissors, threads, needles.

(2) The connecting costume in the slideshow were crafted during the KUV (kunstnerisk udviklings virksomhed translates to artistic research) project Textile Techniques as Potential for Developing Costume Design (link). The slideshow shows connecting costume versions in-process and In the images of dance and acting students (from the Danish National School of Performing Arts) that explore some of these connecting costume prototypes.

(3) In other contexts I have physically explored costume through wearing – alone and collaboratively with colleagues and/or with students. These explorations were often situated in private and ‘controlled’ settings – for example in indoor studios or rehearsal spaces – with a duration of one to three hours. However, I was not entirely without experience of rehearsing with costume in an urban setting. In the performance project “Traces of Tissues” we – Sally E. Dean, six performers and I – had all rehearsals taking place in different parks in the United Kingdom, Denmark and the Czech Republic. Nonetheless, in “Traces of Tissues” I was mainly placed outside in the role of co-curator with Dean of the performance material that the six performers co-produced.

(1) On their website Metropolis write that “Metropolis is a meeting point for performance, art, city and landscapes – an art-based laboratory for the performative, site-specific, international art. Copenhagen International Theatre is behind Metropolis and has initiated and created a large number of festivals and projects in Copenhagen.”

During the festival I collaborated with the Metropolis team: Trevor Davis, Katrien Verwilt and Louise Kaare Jacobsen.

(1) Lagerström writes that walking in public “invite[s] the surroundings and passing observers to influence the wanderer” (Lagerström 2019, 22). It is interesting that Lagerström (in the book) has the need to introduce the term “teatermarkörer” (Lagerström 2019, 80) – which I suggest translates to theatre marker – instead of costume/costuming. Lagerström suggests that ‘theatre markers’ “move something [an event] away from the usual [everyday] situation or environment” (Lagerström 2019, 48) and when using ‘theatre makers’ or costume and make-up indicates that a performative (inter)event(ion) is occurring in a public environment. Moreover, the ‘theatre markers’ implies that the wanderer appears as stranger and evokes or provokes diverse reactions from spectators (Lagerström 2019, 77). I have translated the Lagerström quotes from Swedish.

(2) The conference was held at Stockholm University of the Arts, Sweden. October 17–19 2024.

(3) For example, in Suriashi as Experimental Pilgrimage in Urban and Other Spaces (2022) choreographer Ami Skånberg writes that the aim is that her practice-led-thesis “contributes to the burgeoning field of walking arts practice, bringing a Japanese dance-based practice into a dialogue with debates and practices of Western dancing and walking” (Skånsberg 2022, 3). In Mixed reality in Public Space Expanding Composition Practice in Choreography and Interaction Design (2023) choreographer Marika Hedemyr studied and created walking experiences for audiences where mobile phone-based augmented reality (AR) become mixed with reality (MR). Skånsberg’s practice springs from Japanese traditions whereas Hedemyr’s emerges from site-specific performance contexts.

(4) During the PQ15 festival 83 groups of masked and costumed people walked in the centre of Prague.

(5) As mentioned, Community Walk pointed towards Wenger‘s “community of practice” and how we participate in practice and towards how I understand the Danish word fællesskab (community). Embedded in the Danish word fællesskab (community) is that you invest yourself in what we (as a smaller or larger community) do in common.

The walking and talking ritual

The main ritual of Community Walk was walking and talking. ‘Walking’ was an invitation to physically sense each other through the costume and jointly navigate and negotiate the costume, people who we passed or who passed us and the urban/nature elements.

‘Talking’ was an ambition to have dialogues on what constitutes communities as my contribution to Wa(l)king Copenhagen was to ‘take the temperature’ on the state of our communities. I did not search for answers, and I did not intend to lead our dialogues in a specific direction. My ambition was to spark fluent dialogues between us. However, in this research I do not intend to unfold or discuss the state of our communities, and I will not retell or reveal the participants’ personal stories.

My interest lies in how the concept ‘walking and talking’ orientated the walking explorations. UU described that ‘walking and talking’ was almost “like holding hands”. UU reflected that this style of walking and talking side by side, more resembled their daily life than their performance practice.

In the situations of literally ‘just’ walking and talking, the connecting part of the costume dangled between us, indicating that we forgot or did not pay attention to the costume. On the other hand, the dangling connection touched the ground and created subtle sensations – at times almost imperceptible – of different pavements, structures and coatings such as cement, tiles, cobblestones, pebbles and grass. We hardly addressed these sensations, but the awareness of the dangling connection slipped in and out of my attention throughout the twelve hours. As such, these subtle sensations made me aware of different surfaces and thus created spatial orientations.

Several of the participants reflected that ‘walking and talking’ was like two tracks of communication that battled to become the driving force (Østergaard 2024, 177). At the same time, UU reflected that

“if you didn't feel like talking or didn't feel like moving, you could switch between them. In some way, the physical connection could almost interrupt the conversation. In any case, I did not experience it [talking] as a limitation, more an expansion and increasing of one's possibilities.”

As was the case with UU, I experienced that the participants quickly and naturally switched between and/or blended verbal and physical dialogues.

Starting points and framings

Community Walk brief (30 July 2020)

On the Metropolis website I introduced Community Walk:

In a time when we are encouraged to keep distance from other people, Community Walk is an investigation of the physical presence of other people. How do we meet and greet when familiar rituals such as handshakes and hugs are discouraged? How do we recognise the presence of other people when we individually and collectively perform social control in the fear of an invading but hidden enemy? Over 12 hours, I will together with 12 guests explore proximities in and distances of communities. Caused by the places and the people we pass; we will have physical and verbal dialogues on the concept of community. What is the “state” of our communities? (I have translated the text from Danish)

I invited six women and six men to participate. The participants were either trained/educated and working as dancers, performers, actors and/or choreographers, or educated and working as designers within costume, scenography, fashion or visual art. The participants were between twenty-two to fifty-six years old, had different European backgrounds and identify themselves as male, female or queer.

Three of the participants had been a part of AweAre – a movement quintet, and I invited them to have a shared reference point. I had collaborated with several of the participants in other performance or artistic contexts. For example, one had hired me to design costumes for several performances, one I had hired to perform in a performance project, and several participants and I had been hired by performance collectives or theatre institutions to collaborate on different performance projects. Together with one of the participants we had co-created several independent textile/costume experimental projects. A few of the participants were former students and several of the participants I consider friends.

The Metropolis festival paid the invited artists a fee, which I used to hire a videographer, who was also the last participant, to document Community Walk with video and photo. Thus, the third person in Community Walk was the videographer that followed us a by walking behind, in front and/or beside us. The participants signed an informed consent contract that Community Walk and the video/photo documentation would form part of this artistic research. Throughout this artistic project I will use the gender-neutral pronouns ‘their’ and ‘they’, not only to anonymize the participants but in respect of the different pronouns they use for themselves.

Naming the project

In naming my contribution to the festival, I wanted to point towards the notion that walking is an act of doing something in common which potentially create a sense of community. As I use and understand the Danish word fællesskab (1) (community), imply that when you invest yourself in what we do in common you also offer something to the common doing. By investing ourselves in the common doing we collectively create a community or relational space.

Apart from that, I was inspired by how educational theorist Etienne Wenger, in the context of “community of practice” (2) (Wenger 1998), describes participation. Wenger suggest that participating involves

the social experience of living in the world in terms of membership in social communities and active involvement in social enterprises. Participation in this sense is both personal and social. It is a complex process that combines doing, talking, thinking, feeling, and belonging. It involves our whole person, including our bodies, minds, emotions, and social relations. (Wenger 1998, 55–56)

With Wenger’s definition of how we as humans participate in communities of practice, I decided to use the English word community. Therefore, in the name Community Walk, the concept of community contains both a reference to Wenger and to the Danish words fælles (common) and fællesskab (community).

The walking routes

In preparation for Community Walk I planned a detailed walking route that led from one transitional location to the next (3). At each location a new participant would enter the costume. As the transitional places had to be easy to find, I chose places like squares and train stations.

My overall ambition was that Community Walk related to walking routes and/or outdoor places where I meet friends and that were part of my daily walks/routines during the Covid-19 lockdowns. The walking route travelled through various urban environments, for example different parks and squares, pedestrian streets, sidewalks of busy roads and quiet streets and harbour sites.

The five rituals

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic governmental restrictions, audiences were not allowed the gather. Consequently, Metropolis arranged that audiences could follow the Wa(l)king Copenhagen festival via live streams on Facebook. Thus, every artist that contributed to the festival, was asked to live stream five to ten minutes every hour – in total each artist produced thirteen live streams. During Community Walk we had no idea whether any audiences followed our live streams. With the insights that I gained during Community Walk I would have organised the live stream situation differently. However, in this artistic research the focus is not to discuss the live stream situation and its implications. Still, the requirement to live stream had an impact on how I framed Community Walk.

As a framing I created five simple rituals that I repeated with each participant.

- Welcome ritual: greeting a new participant.

- Transition ritual: undressing/dressing, passing on the costume to the next participant.

- Testimony ritual: the departing participant shortly reflected on their experiences of the walk. This ritual mainly served Wa(l)king Copenhagen but as it turned out it has also formed a valuable part of the documentation for my research.

- Farewell ritual: greeting the departing participant. I asked each departing participant how they wanted the new participant and I to bid them farewell.

- Walking and talking ritual: exploring the costume and jointly navigating elements, the environment and people who we passed by or who passed by us. In the introduction to the participants, I wrote, for example, that “walking and talking” would be about physically exploring how we could sense each other through the costume, and that, prompted by the places and the people who we passed, we would physically and verbally reflect on the concept of ‘community’.

During the live stream situation, that included the welcome, transition, testimony and farewell rituals, I asked each participant to share a few insights to our dialogues and to share their experiences of being connected through a costume. The participants’ statements in the live stream situation, are part of the data that I call ‘testimonies’, where the other part includes short self-recorded respond on the experience that I asked each participant to send me in the hours after their participation. In the differnt pathways I quote the participants’ statements from their testimonies and from interviews I did with each of them individually after Community Walk.

Hosting as sharing

Sara Ahmed’s reflections on “the politics of sharing” (Ahmed 2006, 123) originates from an analysis of orientalism and whiteness as a straightening device that produces straight lines and reproduces racial hierarchies (Ahmed 2006, 121). Whiteness and the racial oppression it produced is highly relevant to acknowledge as a white person; however, this is not the topic of this research. Still, I am white, and I experience the world from this perspective. As such, I must always discover and uncover the bias that my whiteness produces. I must constantly be willing to re-learn and re-educate myself. In the context of hosting, Ahmed’s arguments on the politics of sharing and its implications are useful.

Sharing

I have suggested that the costume created a shared space between us. Ahmed writes that

while sharing is often described as participation in something (we share this or that thing, or we have this or that thing in common), and even as the joy of taking part, sharing involves division, or the ownership of parts. To have a share in something is to be invested in the value of that thing. […] So the word “share,” which seems to point to commonality, depends on both cutting and on division, where things are cut up and distributed among others. (Ahmed 2006, 123)

Ahmed notes that sharing is cutting, dividing and having a share in or part of something. Ahmed reminds me that there was an uneven share between us who participated and in the relationships that emerged with by-passing people and urban/nature elements. As such, it seems crucial to explore what, with whom and what parts were shared. Even though the costume created an intimate and shared space between us, Community Walk was place in public, which meant we never possessed the spaces that we walked through and/or the places where we temporarily paused. Public spaces are in principle accessible to everyone. However, it is debatable whether we – the public – always share the public places with those human and more-than-human others that are present. In several situations during Community Walk it seemed as if sameness was a matter that mattered in public. Even though we shared the public space with other people we had to navigate their responses. In some situations it felt as if we, perhaps due to our appearance, existed in a parallel space where we had to negotiate whether we had some kind of share and/or how we could share the public space or places with these people.

Walking in public connected through and with a costume, we shared experiences of appearing queerer than alike, of being included and excluded and of including or excluding others in our shared space. Even though we shared the experiences of walking in public it did not our experiences was shared. The shared space was a relational encounter between us and we firstly had to become aware of our own expectations towards our creative relationship. Secondly, placed in public, many ‘things’ happened simultaneously, which often disturbed and prohibited us from focusing only on exploring our relationship with costume, and thus our shared space. Thirdly, we only had one hour together which implied that we often did not manage to share our different expectation and how we experienced our encounter(s).

Sharing part(iality)

In Community Walk I had divided the twelve hours into twelve parts. In the interview NN reflected that “at first, what struck me the most was to jump into the chain of actions and the knowledge of my place within this twelve-hour history.” NN unfolded that the participants had a partial whereas I had the full twelve-hour experience of the event. Nonetheless, for one hour we co-authored the encounters we had. In our shared space, we experienced that these encounters, at times, were co-authored by accidental guests and/or were the effects of by-passing people with whom we shared the public space. However, it is doubtful that the accidental guests experienced that they co-authored or even shared an encounter with us.

In their interview KK proposed that “the costume was like an archive that gathered all the different information. The costume became the connector and the vessel.” KK suggested that the costume collected our different experiences which indicates that there were connections and perhaps a sharing between everyone who participated in Community Walk – even though most of the participants did not meet and/or did not know each other. KK proposed that the costume as an archive crafted a metaphorical space between the twelve participants. In the interview situations it was clear that the costume had crafted a space between us, and the participants shared how the costume space resonated in their embodied memories. Most of the participants reflected that our one-hour explorative walk transformed our relationship into a more playful one than in our prior encounters. They felt enriched and surprised that our encounters made them daring and inventive in the way that they and we encountered the public space, and several mentioned our dialogues as inspiring.

Despite my own involvement throughout the twelve-hour walk, my experience was also partial. I can never fully grasp or know what the twelve participants experienced and thus I can never fully unfold Community Walk and its implications. I can uncover my partial perspective of the experiences and encounters that I shared with the twelve participants. Ahmed reminds me that “the gift of life is often a gift of parts, which are unevenly distributed” (2006, 123). Even with my partial perspective I spent time with each of the twelve participants while they only spent time with me. As such, I had the gift of exploring the costume with twelve different participants and the twelve participants gave me the gift of participating and responding to the costume, our shared spaces and the encounter(s) we had with others in different ways. Moreover, as the consistent participant, I received the gift of exploring the complexities of hosting an event like Community Walk.

Hospitality as sharing points

In Navigating in the Landscape of Care: A Critical Reflection on Theory and Practise of Care and Ethics Eva Skærbæk writes that “every one of us holds some of the life of the other in our hand” (2011, 44). Skærbæk translates a well-known quote by the Danish theologian and philosopher K.E. Løgstrup which I relate to as a part of my cultural baggage. Skærbæk unfolds Løgstrup’s words by suggesting that “we are interdependent in the sense that we influence each other with what we do and say and by what we do not say and do; we are each other’s authors” (Skærbæk 2011, 44). Skærbæk suggest that we co-author each other’s experiences, which implies hospitality is more than the duty of the host; it is an ethical demand and a call to attend to the fact that we affect each other. For example, how we are hospitable towards other people affects what we can do and become together. I therefore suggest that embedded in hospitality is not just an expectation of but a demand for reciprocity in the exchange between the guest and the host, where they orientate themselves towards their relationship as socio-cultural exchanges. However, in the socio-cultural exchanges the host (1) cannot hide behind a role but must reveal and invest themselves in the relationships with the guest by being hospital (gæstfri) towards cultures and the potential unfamiliarity or otherness of the guest. Moreover, the host must recognise that they depend on and will affect the guest. Even though in their exchange the guest and the host co-author each other’s experiences, the host is still accountable.

Being an accountable host suggests that the host must attend to their socio-cultural expectations towards guests, as these expectations will inform how the host’s hospitality is orientated. Moreover, as an accountable host the host must create conditions that enable the guest to respond creatively and the host must embrace that the guest might respond in ways that are not in line with the host’s expectations. As such, the host must decide how they respond to the guest and the host must act and respond accordingly. I argue that the host – as an act of curiosity and generosity towards the gust – must step aside to explore the creative (in)sights of the guests. By stepping aside, the roles or positions of host and guest become less fixed, which in turn enables entanglements between hosting and guesting, allowing them to become sharing points and openings for exchange.

Communal sharings

In Community Walk I had to step aside to orientate my orientation towards what the participants wanted to offer to our shared space. Moreover, the stepping aside included being beside as a participating partner and exploring what we could do in common. As such, as creative partners the participants’ contributions were paramount. The participants co-authored Community Walk and as co-authors they illuminated sides of the sight that would have remained out of my sight without their valuable (in)sights. Thus their (in)sights expanded my sight of the material-discursive space that we shared and explored in public.

Ahmed suggests that “a queer genealogy would take the very ‘affect’ of mixing, or coming into contact with things that resides on different lines, as opening up new kinds of connections” (2006, 154–155). To use Ahmed’s words, in Community Walk the costume and the shared material-discursive space that it evoked invited our creativities to mix. As we mixed our creative lines, other lines opened that mixed or blurred the borders between who was inside and outside of the costume. As participating host I followed the participants’ crossings, which made me cross lines that I could not have crossed singlehandedly.

As the consistent participant in the series of co-creative pairs, Community Walk displayed a series of we’s (we in plural) that – like small communities – had multiple voices, encounters, qualities and other. In the series of intimate communities (I refer to the Danish word fællesskab that I unfold in Starting points and framings), I had to embrace multi-directional qualities of our communal encounter and multiple times during the twelve hours I had to re-orientate myself – attuning myself towards the guests – as an affect and/or respond to the twelve participants and their creative views. This involved re-orientating my hospitality to include views that were directed or orientated towards sights I did not see.

As a community of participants I learned from and with the participants, for example from their different ways of co-inhabiting the costume and our shared material-discursive space. As such, Community Walk acted unexpectedly and surprisingly as an intervention towards me. The event or artistic project placed me in an unusual situation and the position of participating host amplified that I gained another kind of knowledge placed inside explorative situations than by merely observing or witnessing from the outside. Hence, as researcher and as human, Community Walk felt immensely transformative.