5. Love your lover

In this song I draw direct inspiration from chamber music while arranging the score, albeit not while composing the harmonies or the topline.

I felt Love your lover as a bigger sonoric universe than the other songs, with differences in timbre and instrumentation for different sections of the song. In the recorded version, you can hear a string quartet, with an additional recorded violin on top, double bass, piano, sampled flute, clarinet and bassoon, sampled and electronically modified drums, as well as other sounds created in my DAW.

You can hear the whole song of Love your Lover at the first page.

The classical connoisseur will recognise the source material I used for the arrangement.

EXCERPT FROM FIELD LOG:

7.12.23

Ser på noter till Ravel igen.

Lytter til Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis by Vaughan Williams. Mye inspirasjon her! Den lange høye tonen i starten.

Brahms piano trio B dur 3e sats, oktavene er fin inspirasjon for basslinjene på slutten. Veldig store avstander mellom øverste stemme og underste!

Lyssnade på fagott-sonater for å få inspirasjon til bridgen på forskjellige teknikker man kan bruke. Kom frem til at det ikke var så mye å hente…

Ravel - I andra satsen i sin strykekvartett er det noen nydelige strykebakgrunder når man kommer til A og det andre temaet presenteres. Prøver noe á la disse på andre verset!

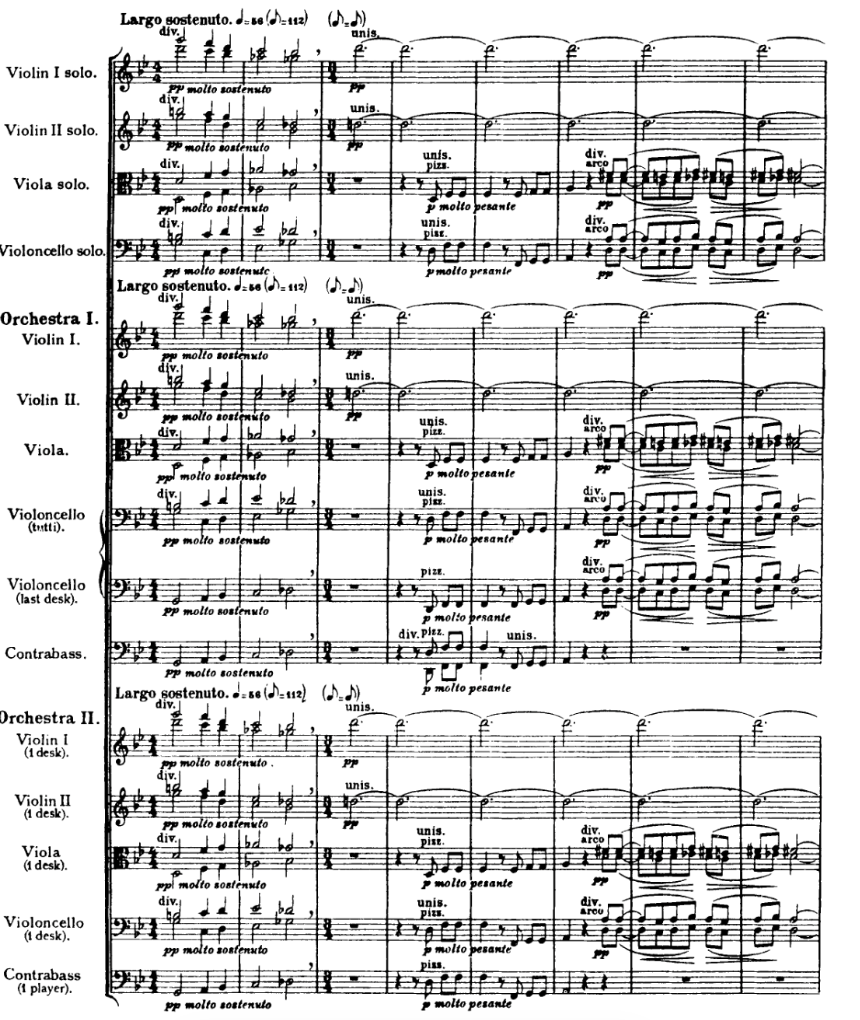

In 1910 Ralph Vaughan Williams composed the beautiful piece Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis. (Vaughan Williams, 1910). Unlike all the other pieces I use as sources in this thesis, this is not set for a chamber ensemble, but for string orchestra. However, it has a rather unusual scoring: not as one large body of orchestra, but as two different string orchestras and a string quartet (the most famous of all chamber groups).

In my case, my primary inspiration is not from the piece as an orchestral piece, but I used it to attain ideas on how to treat string instruments. In my score, I have used some of the instrumental ideas, but also a general feeling I get by listening to the piece.

Placing the openings of the Fantasia <- and my song -> side by side, you can see certain similarities.

While the key, rhythm, scoring and voicing choices are quite different, I would like to draw attention to two characteristics of the opening bars: In both songs, the scores open with downward, mainly scale wise movement in the upper instrument, countered by upward, scale wise movement in the lowest.

There is also a high, long note being held across several bars in both pieces. I loved this effect in the Fantasia and so chose to deploy it myself, but have combined it with the first figure, placing it from the very beginning of the piece. I have also placed it significantly higher, almost on the threshold of what is comfortable to listen to.

A second piece wherefrom my scoring choices can be traced is Maurice Ravel's iconic String quartet, written in 1903. (Ravel, 1910).

In many places throughout the piece, Ravel uses tremoli in different sections, fleshing out the harmonics in the composition, but also creating an eerie, airy, special timbre in the strings. I love the sound produced by string instruments using this technique, and the way Ravel uses it in the quartet, often set in contrast to other parts playing long legato melodies, is very special. This is the inspiration for the use of tremoli in the middle voices in Love your lover.

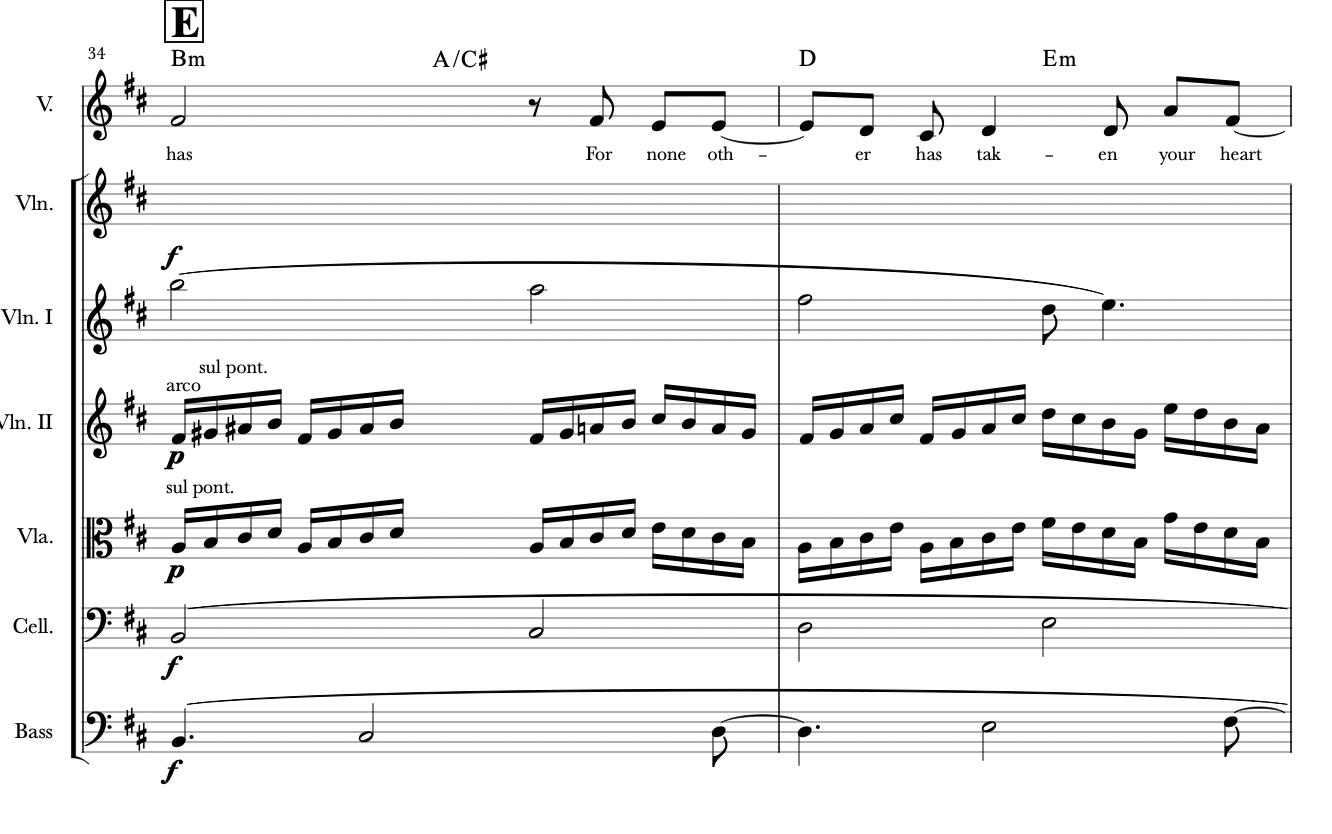

In the second movement we see 16th notes in the middle instruments. These give a sense of a rhythmic pulse, and the arpeggi give the middle voices movement. There is a bright, melodic violin on top.

In my 2nd verse, I wrote similar 16th-notes for the violin 2 and viola (maybe with more emphasis on the melodic content).

You can also see that I’ve written sul ponte (playing with the bow close to the bridge).

When I first practised with the string quartet, sul tasto got too screechy and unintelligible on the fast passages. We tried changing to sul tasto (playing with the bow close to the fingerboard). While a little more concrete than I had imagined, it was more pleasurable to listen to.

The second verse is also where I introduce the rhythmic section and synth bass for the first time. Skriv tid i første video, med lenke til dit.

As the strings are very bright and piercing, I wanted the drums to be contrasting and to introduce another, rounder, more muffled dimension. On the electronic drums I chose to add high-cut filters on many of the different components.

The bassline, I had determined already at the piano-version demo stage of this song, was to use a Brahmsque-move at this stage. A trick Johannes Brahms often uses is to anticipate the next harmony in the bass. You can hear at 00.45 when Radu Lupu plays Brahms op 119 no 1, that the bass shifts one eighth note earlier than the right hand. (Brahms, 1893/1987).

I was also surprised that I didn’t seem to need much drums.

The second violin and the viola simply played the part I would mostly associate with a high hat or a shaker, and together with the early bass downbeats in the piano, the whole song already had forward drive.

I sent the two middle string instruments to a return track with a rhythmic delay, to heighten this rhythmic effect, and increase the sense of the “tremoli”-like playing discussed in the previous section.

In the pre-choruses I intended to change character drastically. The piano is introduced for the first time in the 1st pre-chorus, with a deep resounding bass note and dark chords, and far in the background are three wind instruments commenting each other and uniting at the build-up to the chorus. Time instruction again.

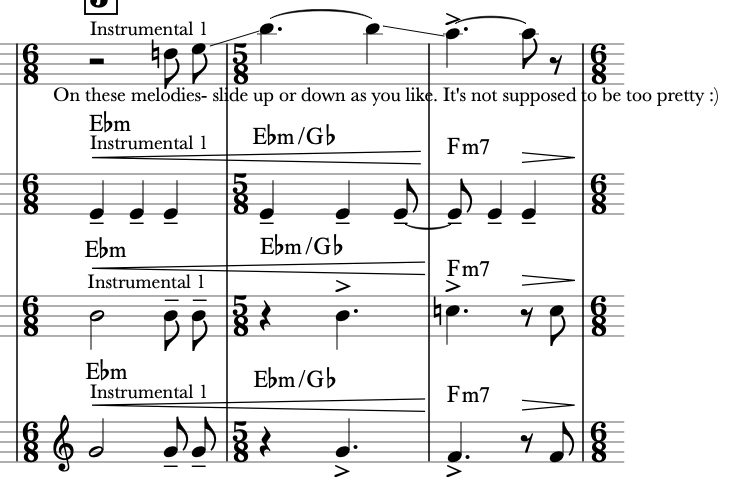

For the bridge I wanted something completely different.

I decided to try a flirtation with the first piece I cited, the Fantasia by Vaughan Williams.

I let the first part of the bridge modulate from Bminor to an easy Bmajor. But quite early in the bridge, at Tidskode i video 1, I changed the mode from B major to B phrygian. This is indeed the mode of the renaissance piece by Thomas Tallis, upon which the Fantasia by Vaughan Williams is built. I tried a few different variations, and ended up with the Spanish phrygian scale instead of the usual one.

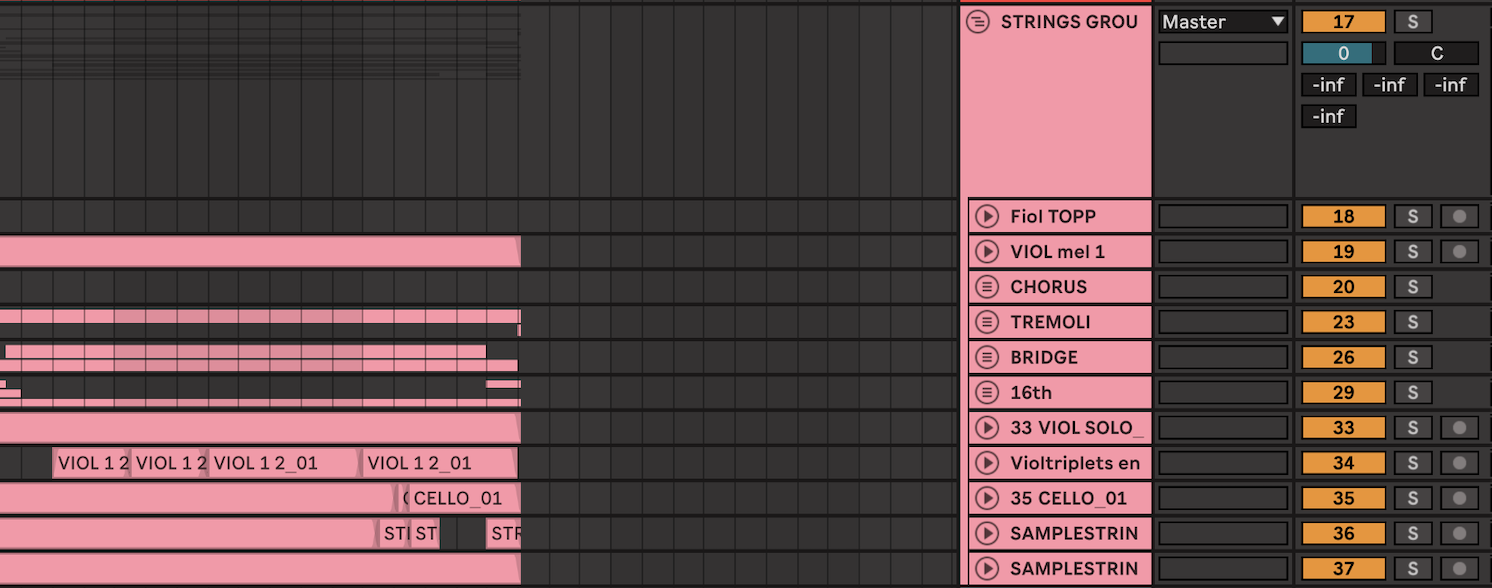

For example: the two outermost voices moving towards each other (violin 1 and cello in the beginning, later bass) I wanted relatively dry and direct. The only reverb I added on these, were on a return track so that the sound did not move away in the mix. The middle voices playing tremolo, I tried with a much wetter reverb straight on the track. Comparison between the first bars of the versions.

I treated subsequent sections in the same way. I have placed an arrow on the string section, where you can identify different subgroups and subtracks within the overall group. Each of these has their own, unique treatment. For example, the chorus is almost completely dry in all instruments. In the bridge, the violin solo is granted more space and a different placement from the violin playing triplets, which I wanted to mesh into everything else. The 16th group, as already mentioned, are dry from reverb but are sent to a delay on a return track.

Live version

Video, press on image to play ->

For the live version I played in my masters concert, I had to limit myself to four string players, and three violins instead of two and a viola. Some changes had to be made in textures and rearrangements of the voicings. For example, as you can see in the first bars, I cut the long high note on the violin referred to in the earlier part of this chapter. Other instrumental adaptations are that the drums are played live, and that instead of woodwind instruments in the bridge, a euphonium is played far in the back of the stage.

All of the previously discussed mixing choices were possible in a recorded version. It is much more difficult to achieve live. While I had highly experienced and amazing sound technicians in my master’s concert that made a beautiful mix in the hall, we didn’t have time to set the sound details of each song. More intricate mixing work would have required a long pre-production of several weeks, and so I settled for a more general mix of the strings.

5.3. Stop motion

Stop Motion is a quite different song from most of the others. Already from its conception, it was less classically inspired than the other songs. I wanted to write a rhythmically driven song based on one note.

I myself do not exactly know where to place this song on a genre-map, but would probably opt for something jazz-pop inspired.

The different genre-references I feel in the song made it difficult to understand which sonic direction it should go in. In most of the other songs, as we have seen, I had a clear reference to pieces or composers, but not in Stop Motion. Even from the vague popular music-genres I mentioned, I didn’t have a specific song or expression in mind.

The only thing I knew for sure, was that I wanted a frantic, hectic feeling, largely driven by the drums.

The easiest way to understand the evolution of the sound to the song, is a timeline. Following are different incarnations of the song, and its development over time.

The overall impression after trying this out, was that it fell far outside my sonic universe, by no fault of the musicians. It was simply the setup that was not right for my expression. Although I had chosen what instruments I wanted based on my feeling of the song, they were not right. Underneath I list some of the things I wanted to keep or discard from the first attempt.

- Keep: I really liked the hectic drum groove.

- Discard: The sound of the keyboard and the bass, not quite inside my sonic universe.

- Discard: The guitar felt out of place. This was by no fault of the musician, he played it in this manner at my request. I wanted the guitarist to try out a funky way of playing.

- Keep: the solo in two layers in the instrumental post-chorus, in some form or the other. In this version one was the guitar. I liked the melodies I had written, and I liked that the two different voices had very different characters and weren’t played by similar instruments.

- Keep: I also liked the quarter notes in the instrumental parts, suggested by the keyboardist. They accentuated the polyrhythmic elements, but again, rhodes was not the right instrument.

The band version became almost an elimination by trying-process. I got a great job from my fellow musicians, but I realised that the direction was not right for my project as a whole. I had to keep looking.

3. Loop station solo version

Video. press on image to play ->

For a concert at Kilden, I was asked to perform something solo. I decided to do a loop-pedal version of the song. In some ways, it meant going back to my basic idea of the song.

Working with a loop pedal, you are by definition repeating the same sounds over again, and I felt the risk of losing variation. I still felt the instrumental choices were not quite accurate. Of course, you can also hear in this video that I should work with my mixing on the looping station.

I also had to delete an instrumental part. I recorded a 4 bars long loop in 4/4 on the loop station. While the chords are the same in the instrumental part, the time signature changes to ⅝ for one bar, 6/8 for two, and then back to 5/4 again. The loop station cannot change time signature, and so my choice was between cutting the instrumental part or trying to play the instrumental part without any loops. The instrumental part is supposed to be a top point in the energy during the song, and I thought that would be difficult to achieve with the second choice, and so decided to skip it instead.

4. Loop station with drums

<- Video, press on image to play

The summer of 2023 I went on a small tour performing a set of my own songs, including Stop Motion. I thought it would be useful to try out this song, as one of the newer songs of the set, with the loopstation and drums.

Now, I started to feel that things were at least in the right direction, if still not landed. I loved the frantic, fretted drums in combination with some clear sounds, and everything was lifted to another level compared to the solo version of the last video. It also felt like enough different elements in the song within the loop station, although they were not the right ones.

The main problem still remained though: I still didn’t know what the sonic universe of the song would be, and how to tie it in with the others.

5. DAW version with recorded drums

In the autumn I started the recording process with the drums as the first instrument. With the drums in place, I was free to start experimenting with different sounds in my DAW.

It was only at this stage that I realised that the sound I had been searching for, was closer to home than I had previously thought. Until now I had almost believed that the song had to be placed under a different project, because it was so different from the others.

It was as I tried many different sounds for the bass, the 8th notes, the melodies and the harmonic information at the chorus and post-chorus, that I also experimented with string samples and felt a spark of recognition. It had somehow entered into my very own sonic universe, and it felt “right”. It felt like something I hadn’t really heard before, yet still familiar to me.

Here you can hear and see a screen recording of the process at this stage. Press on image to play ->

The string samples I have available were difficult to work with in this song, because they have a delayed onset or attack, which made them untight and lagging in the overall sound. They are also orchestral samples, which gave a larger and more expanded sound than I wanted.

Even with these flaws, I was going in the right direction. I wanted to convert this to sheet music, and record it with a string quartet and a double bass.

The sheet music I wrote for the recording with this string quartet (plus a violin doing an overdub), gave quite sparing information. I wanted to save myself some time and wrote very little on how to play apart from the notes themselves.

I also sent an audio demo version to listen to, with all the accents and dynamics I wanted, and assumed that it would be natural to imitate the demo.

However, I assumed incorrectly. The performers played very true to the non-informative and “neutral” sheet music. Audio information seemed secondary to the printed score.

6. Latest demo. Not finished yet, but finding its place

As I had recorded a string quartet, I felt that it fit the song well. Both the string quartet and the bass are recordings of practice sessions, to there will be a final recording at a later point. I still liked how different the quartet was to the orchestra samples, not only because they were live and the other version was made of samples, but because there is a different focus in the sound.

The latest bounce you hear here, is not a demo version, and far from finished. However, I do feel that the character is going in the right direction there.

The sheet music I wrote for the recording with this string quartet (plus an extra violin part recorded as an overdub), gave quite sparing information. I wanted to save myself some time and wrote very little on how to play apart from the notes themselves.

I also sent an audio demo version to listen to, with all the accents and dynamics I wanted, and assumed that it would be natural to imitate the demo.

However, I assumed incorrectly. The performers played very true to the non-informative and “neutral” sheet music. Audio information seemed secondary to a printed score.