Se det summer af sol over engen (lyrics: Holger Drachmann / melody: Stephen Foster) - concert with participating audience, The Village, September 2022

I sne står urt og busk i skjul, melody: J.P.E. Hartmann, arr: J. Anderskov, studio recording, take 15

Se det summer af sol over engen, abstracted version (lyrics: Holger Drachmann / melody: Stephen Foster)

- studie recording, without audience, The Village, September 2022

Process considerations

During the process of preparing concerts and recordings, restructuring the song material, altering the musical accompaniment of the songs, recording the music, and testing the concert format with the audience, a wealth of reflections and insights have emerged. I will attempt to outline these working methods and insights below, although many are of a nature that is challenging to convey transparently in writing.

[ Solo ]

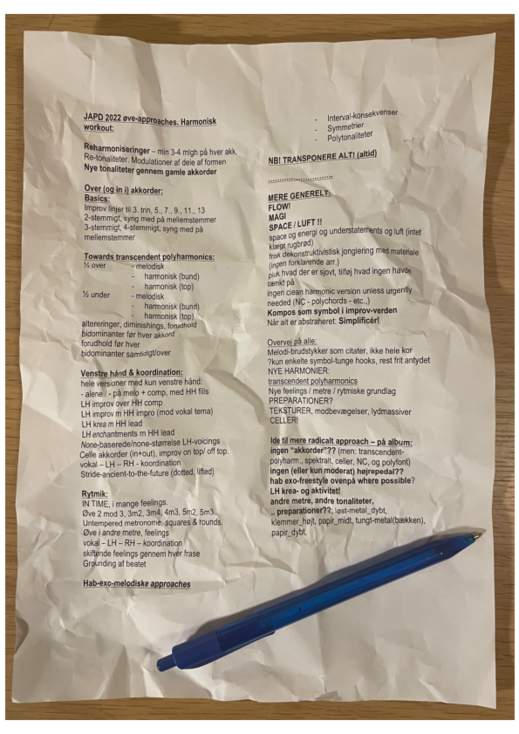

In preparing for how to instruct musicians and singers, as well as for the decision-making processes associated with the musical arrangements themselves, I revisited a piano methodological complex that I have developed over the years, which I’ve labelled towards transcendent polyharmonics in my own notes. This approach involves a series of exercises that all have a multi-dimensional purpose: to deeply familiarise oneself with the material while deconstructing any associations or habitual arrangements linked to it. Overall, the exercises aim to foster a profound auditory and tactile understanding of the material, and to enable the performer to experience an essential core behind the “normal arrangement” of the song. This practice involves a high degree of improvisation, within a wide range of strict dogmas, as I will outline in the following.

Some of the dogmas stem from common jazz pedagogical thinking, such as, for example, improvising melodic lines that ‘must’ pass through the third on every chord – and in the next chorus, the fifth step, then the seventh, ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth steps of the chord. Other exercises are rooted in didactics from the French organ improvisation tradition, such as improvising three- or four-part versions, and singing along with alternatingly the alto, tenor, and bass parts in the improvised arrangement.

Still other exercises are far more destabilising in their effect on the music, and thus on the new associations evoked in the arrangements: For instance, all harmonies might be shifted by half- or whole-scale steps (up or down), while the melody remains in the original key. Alternatively, harmonies could be replaced with diminished, augmented, altered, or bidominant functions related to either the preceding, following, or current harmony.

Some exercises transform the song into an arena for in-depth coordination exercises, systematically exploring the relationships between pulse sensations in the left hand, right hand, voice, and feet. For example: In which of these four locations (left hand, right hand, voice, feet) is the pulse sensation located? Where is the original melodic melody? Where is improvisation / embellishments / paraphrasing taking place? It might involve exercises where tempos, time signatures and feeling/subdivisions are altered.

Harmonisation dogmas might require certain intervals within harmonies to be used or avoided over longer passages. Systematic reharmonisation practices might involve finding five to eight radically different harmonic possibilities at each point in the song – which in turn can be the subject of the melodic studies above.

Additionally, I apply structural and doctrinal concepts described in my previous projects, Habitable Exomusics (which addresses linear and rhythmic concepts) and Sonic Complexion (which explores textural, harmonic, and timbral concepts).[1]

Still other concepts involve dismantling the idea of chord structures entirely: What can replace chord-based thinking or a harmonic dimension whatsoever, if the song is still to be experienced as related to its ‘original’ version?

To illustrate how these approaches could sound, and on what level the transformations operate, it is recommended to listen to the four versions of “I sne står urt og busk i skjul,” on the left side of this text.

[ Ensemble, studie ]

In the studio, during the collective recording process, it became clear that the material offered even more possibilities for development. Several songs were deconstructed in their overall form syntax or in the narrative progression: Can we evoke the entire song with just a single phrase allowing the audience to hear it in full for their inner ears, even though only one phrase is actually played? How little is needed for the song to be vividly clear to the listener, even if we haven’t played it? In other moments, how can we bring the song forth in a more complete form without causing the surrounding abstraction to collapse? How much needs to be agreed upon up front by the musicians? How little can we agree on if the improvised, spontaneous reaction to the moment is to stand vibrating at the centre of the statement?

When we let the normal arrangement of the song fade away, when is it a metaphorical common understanding that we should start from, and when is it more appropriate to construct an actual re-composition that we refer to, before we start improvising over the material? Composing a completely new arrangement of a song is not a problem, but allowing the song to mutate through continuous collective renegotiation sometimes required a metaphorical or metaphysical common understanding to be established.

[ Audience ]

During interactions with the audience, first in the studio and later in concert situations outside the studio, new insights emerged. Firstly, there is the ubiquitous question of clarity. How can we make it as clear as possible to the audience when they should sing along, using the simplest means possible? When some performers act as guides for the audience through the song while others introduce contrasting musical elements, it becomes crucial to show the audience who to follow, when, and for how long.

We also noticed that the mere presence of a singing audience can have a gravitational effect on the improvised dialogue in progress, in a way where the performers sometimes have to remind themselves and each other that contrast is still allowed/needed, even when the audience is singing along.

An important question arose regarding the freedom of the singers in the ensemble. The audience often perceives deviations from the song’s familiar version by one of the ensemble singers as confusing, yet the ability to create contrast between the audience’s and the ensemble singers’ singing is essential to the project’s aesthetic. Finding a way to communicate this nonverbally, in real time, while maintaining the principle that the audience receives no prior instructions, remains a consideration. A question in itself is what kind of freedom the singers in the ensemble have. The audience will often perceive a deviation from the normal version of the song by one of the ensemble singers as a confusing sign, but at the same time, the very possibility of contrast between the audience’s singing and the ensemble singers’ singing is essential to the aesthetics of the project. How this can be communicated, wordlessly, is still under consideration at the moment, as I try to maintain a dogma that the audience is not instructed in advance on what is expected of them.

This also highlights a paradox that the ensemble singers face, where they are soloists with a great deal of freedom, but at the same time bound by being synchronised by the audience, continuously.

One potential solution is for at least one instrumentalist to take over the role of carrying the melody, allowing the singers to deviate without disorienting the audience. But this soes not entirely resolve the somewhat paradoxical situation of the ensemble singers.

Another vital consideration that arose from our interaction with the audience is that, at times, clear prior agreements on who carries the melody are essential to allow the emergence of the kind of spontaneous musical freedom central to the project’s aesthetic.

A couple of times, we performed scaled-down versions of the project, such as in a duo format, where similar dynamics were at play. With only two performers, the gravitational pull towards the ‘normal version’ of the song can seem even stronger, making introductions and improvisations feel unnecessarily short. Additionally, with just one singer, it becomes even harder to communicate to the audience that not everything the singer does has to be followed by the audience – without becoming overly explanatory in the artistic statements. And, this one singer also has an even greater communicative task of clarifying whether it’s time for the audience to sing along or not until later.

Different concert venues and situations offered huge differences in the audience’s “song readiness.” In some places, the melody only had to be hinted at a little bit before the audience broke into song. Although this was premature in relation to our original plans, it could seem charming and vigorous. With only two performers, the piano accompaniment also tended to gravitate towards the functional (carrying the melody) and away from the creative, reinterpretive (building a world, enchanting the known through unexpected choices). Additionally, it became more difficult to establish an independent, audience-contrasting rhythm with only one instrumental performer. I realised that for the project to be able to scale up or down while retaining its essence, three performers seem to be the minimum number needed to maintain the desired contrast between the audience and the ensemble. This may be due to the reason that the desired contrast between audience and performers requires that some performers clearly take the audience’s side in the opposition, while other performers operate directly against it.

[1] Both are published at Research Catalogue: Habitable Exomusics (completed 2015) is to be found at https://www.researchcatalogue.net/profile/show-exposition?exposition=397815, and Sonic Complexion (completed 2020) at https://www.researchcatalogue.net/profile/show-exposition?exposition=740085. See also an overview of published research (primarily artistic research) at https://jacobanderskov.dk/?page_id=927.