Lamento della Ninfa

Caravaggio’s representation of the woman figure isolated in a circle/oval of grief in La Morte della Virgine or of remorse as in the previous portrait of Maddalena Penitente, could find, as mentioned in the second part, its musical translation with the closed and isolated character of the Lamento d’Arianna.

Thirty years later, the three parts of the Lamento di Ninfa included in the Eighth Book Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi, make a clear contrast with the almost direct musical response to the syntactic structure and emotional impact of Rinuccini’s words in the Lamento d’Arianna. After the incursion in the exploration of the surface and the senses inspired by Guarini and Marino’s poetry in his Concerto, Monteverdi turns again to a traditional form and goes back to the darker themes of lamentation of his Sixth Book.

However, Monteverdi’s choice for the lighter poetic form of the canzonetta in Lamento della Ninfa, based on Rinuccini’s canzonetta Non avea Febo ancora,- a nymph lamenting her betrayal by her lover watched by three shepherds who comment on her situation,- seems to combine the freedom of his previous compositional experiments of the Seventh Book, with a concept which was already used in his madrigal T’amo mia vita from the Fifth Book of Madrigals, in its musical distinction between narration and direct speech, and the Scherzi Musicali in its contrast between soli and tutti strophes.

An example of this freedom of form is the incorporation of the original refrain at the end of each strophe, Miserella, ahi! Più no, no; tanto giel soffrir non può, in the texture of the middle section, eliminating it totally from the first and last section. In its free interpretation of the text, removed from the original strophic structure and suggesting a more dynamic balance between music and words, Monteverdi chooses a classical division in three parts: two symmetrical sections sung by the trio of male voices and a middle part in a triple- time aria sung by the soprano, with the incorporation of the refrain sung by the trio in a responsorial way.

Due to the isolation of the female voice expressing the emotional nymph’s struggle, brought to the foreground of the musical structure, (Maddalena in La Morte della Virgine), the male voices assume the role of both commentators and witnesses of the nymphs suffering, (apostles) interacting with her in the middle section, changing the strophic character of Rinuccini’s canzonetta into a small scena in genero rappresentativo.

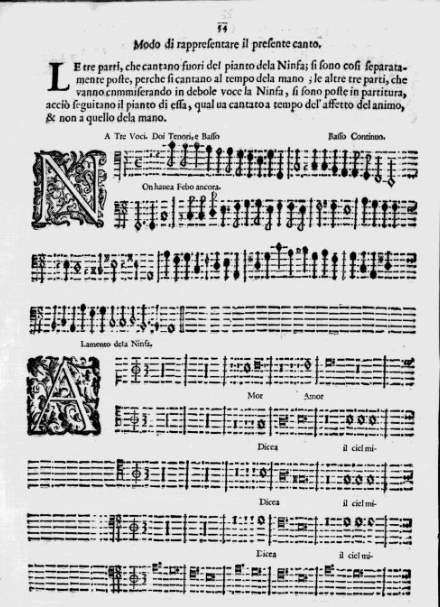

Monteverdi’s indications in Lamento di Ninfa, clarify the differences between the two symmetrical narrative sections sung by the male voices “cantato al segno della mano” (sung to steady pulse) using a homo-rhytmic texture, and the central place occupied by the nymph’s lamentation “cantato all tempo dell animo” ( following the dictates of the heart) in a triple-time aria used over a descending tetrachord ground bass (ostinato).

Similar to the way in which Caravaggio reduces to the minimum or even erases all recognizable landscape or architecture from his dark backgrounds, making in that way the action and the figures of his paintings even more prominent due to the contrasts of dark and light, Monteverdi’s use of the ostinato in the bass line of the Lamento della Ninfa,- in what became a common feature in the seventeenth century opera lamento arias,- works both as an unifying expressive element and simultaneously enhancing the power of the human voice, using the melodic line and not the words, to achieve an emotional representation.

Part 4. Façade, Conclusion

La Morte della Virgine

Thirty years after the conclusion of the interior of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, in the last year of his career which ends with his tragic death, Borromini concludes the façade of the church. His first commission would be his last, a circle that closed a life’s work, in a unique and personal contribution to seventeenth-century baroque architecture.

The same period of time, is what takes Monteverdi from the achievements in Lamento d’Arianna to the theoretic enunciation in the preface of his Eighth Book Madrigali Guerrieri e Amorosi from 1638. One year before the first representation of Arianna in 1608, Caravaggio’s La morte della Virgine from 1606, is bought by the Duke of Mantua, after being rejected by the Order of the Descalced Carmelites which commissioned this work for the church of Santa Maria della Scalla in Rome.

The work was exhibited to public view at the Duke’s ambassador’s house in Rome, between 1 to 7 April 1607 and later sent to Mantua to join the Duke’s outstanding art collection. Giovanni Magno, the ambassador, describes Caravaggio in one of his letters as "one of the most famous modern painters in Rome, and this painting (La morte della Virgine) one of his best works." In this way, the painting brought to Mantua the fame of the painter and the scandal of its rejection by the church.

Like so many of his contemporaries,- among which the young Peter Paul Rubens who was working at the Duke’s court at the time and had recommended the painting’s acquisition,- Monteverdi, who was still at the time the Duke’s Maestro di Capella, would have likely heard of, if not seen, the novelty and intensity of Caravaggio’s personal interpretation of the theme of the Dormition, "involving the spectator with drama and meaning simultaneously", according to Pamela Askew.

If we could travel back in time and enter the gallery of the ducal palace where the painting was exposed, following the hypothetic steps of Monteverdi coming from the left side of the room, he would first be struck by its size and the natural scale of the figures represented. In its disturbing darkness that seems to keep all light inside a room whose space is only defined by the wooden ceiling beams, his eyes would probably first fall on the dead body of the Virgin, illuminated by a cold light that comes from an hidden source on the left.

The Virgin is lying on a flat wooden support or tavola and is dressed in a simple red dress that reveals a body that is swollen and rigid by the signs of death.The placement of the tavola obliquely to the picture plane, extends her body directly across the line of sight, her stretched left arm, a reminder of Christ’s death in the cross unifying mother and son.

Disposed in a counter diagonal on the right side of the body, the apostles occupy a space that is dense and dark with sorrow, consternation, awareness and absorbed contemplation. This display of emotions shown by their faces and gestures, converge in the middle to the figure of the apostle Paul who raises his hand in full light, the only one that seems to be aware of the Virgin's imortality.

Dominating the upper part of the painting and balancing the overall composition, a huge red cloth hangs from an uncertain point outside the frame. Monteverdi would very likely appreciate this oversized theatrical gesture, the red colour announcing the presence of Christ and his flesh, with its curves echoing in colour and shape the drapery of the Virgin’s red dress, contrasting dramatically in its movement with the rigid stillness of the dead body.

Nevertheless, it would be the figure of the young woman seated in the foreground of the painting where his eyes would probably stay longer, surprised by the novelty of a single mourning female figure, not yet seen in the Italian pictorial tradition. Maddalena who prepares for her task of washing the dead body of the Virgin, suggested by the copper basin beside her, is overwhelmed by her emotions. Isolated from the apostles in her own circle of sorrow, her shaken weeping body detached from the pictorial limits into our own space.

In the Death of the Virgin, Caravaggio has stripped both theme and image to essentials so that a symbiosis of reality and symbol is free to operate in an open field and to direct its impact toward the spectator who, in confronting it, is, ideally, shocked into a recognition of a mystery inherent in a death that appears at once so humble and lacking in formality and yet so majestic and profound.

The division in two main horizontal sections, has a direct correspondence with the first order of the columns in the interior, the undulated cornice on top of the first order announced in full expressive force in the exterior. This horizontal element which could remind us of the nymph’s vocal line in its freedom of form, accompanies in his undulation the shape of the wall. This movement is mostly generated by the juxtaposition of two concave lateral sections and the central convex section of the main entrance, which replicates the sweeling of the space inside. A movement that is accentuated by the verticality of the monumental Corinthian columns which have their continuation in the superior section. This upward impulse seems to converge towards the central medalion with the statue of San Carlo Borromeo, to whom the church is dedicated.

The undulating wall of Borromini's invention gave flexibility to stone, changed the stone wall into an elastic material.

Conclusion

As it was mentioned in the introduction to this research, the purpose of my incursion in the musical, spatial and visual world of Monteverdi, Borromini and Caravaggio, did not have the goal to find answers to the many question my analyses raised, but to show a way to look at the works from different angles then only those that we normally associate with their specific disciplines. Doing that, my space of interpretation expanded enormously, accepting the risks that the freedom I took during my progression could lead me to dead ends but also to associations that were almost surprisingly exciting and logical, like something that has always been there but not yet made visible to my eyes.

Illustrating these words, Caravaggio’s Maddalena Penitent and Narciso, examples of the poetic lyricism of his youth, find their musical counterpart in the imprisonment of sorrow and remorse in a perfect oval, the geometric equivalent of the octave, present in Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Árianna, or the duality between reality and illusion in the duets for two equal voices in his Seventh Book of Madrigals, Concerto.

Included in this same book, Con che suavitá, for solo voice and a triple instrumental choir, seem to defy all classification of genre, introducing a novelty in its interaction between voice and instrumental setting, comparable to the centrifugal and expansive compositions in both Caravaggio's Martirio di San Matteo and Crocifissione di san Pietro.

Contrasting with these two paintings are the representations of the mystic moments of the conversion of the apostles Matteo and Paolo, and above all the suspended time of the Virgin’s Dormition. In these examples, Caravaggio's representation of the transitional moments, is made by setting the figures in a deep dark space that evokes stillness and silence, broken by a conducted light that either indicates the way or blinds, or a red curtain that evokes both the Virgin’s imortality and the theatrical nature of the staged mourning scene.

The symbolism of Caravaggio’s large scale paintings, “making the visible most powerfuIly evoking the invisible”, in the words of Pamela Askew, reverberates in the illuminated space of Borromini’s church of San Carlino, in its “musical” interpretation of the trinitarian theme,Tree et uno asieme, finding its most expressive feature in the surface of the Dome which stucco figures seems to quietly expand in a silenced Universe.

In its interaction with the city outside and therefore the human world, the complex harmony achieved inside the church is brought to the exterior and left exposed in a theatrical, interactive façade, which comes alive by the sharp contrasts of light and shadow and the dynamism of the curved surfaces.

Epilogue and aknowledgments

Being a personal interpretation, this research has giving me the opportunity to bring together my first passion for the visual Arts throughout my youth, with a two year course in a school of Arts, my following studies and practice as an architect and my career shift to music and singing.

By connecting these three artistic forms, the path I followed in this research was one that used intuition as both a starting point and an important instrument of analysis, in the same way that an architect departures from a first sketch, an embryonic image waiting for function, symbol and geometry to be further materialized into space and form.

A further exciting development, is the fact that the theme of my research will be the basis for a new concert program, with the tittel "Architectuur van emoties", to commemorate in 2020 the 25th jubilee of the baroque ensemble La Primavera, from which I am a member since 2005.

The concert will be divided in four parts, corresponding to the four levels of San Carlo alle Quatro Fontane: Monteverdi madrigals, duets and solo works, with the projection of the related Caravaggio paintings, together with complementary texts and poetry. With this, the ensemble aims to enlarge the knowledge and the enjoyment of Monteverdi's music by means of a complementary visual and spatial experience.

As last, I would like to thank everyone who had a role in the realization of my work. In order of "appearance", my friend and colleague Ana Sanchez Donate for challenging me to follow the master research program at the Royal Conservatoire of the Hague, my friend architect Francisco Teixeira Bastos who convinced me to accept the challenge, my two supervisors Johannes Boer and Erwin Roebroeks for all their time, great advise, expertise and encouragement to follow and deepen my own ideas and intuition. My friend the theorbist Regina Albanez, with whom I share the love and admiration for Monteverdi's music and the discussion of my ideas, my friend Madalena Pereira for sharing the experience of the works of Borromini and Caravaggio in Rome and the intense moments of artistic communion. The ensemble La Primavera for their enthusiasm, support and believing in my project from the beginning. My colleagues of the master circle and the lector Paul Craenen, for their important feedback these last two years.

My colleague Mike Weston, for all his kindness, encouragement and last revision of my texts and as last and above all, my husband Ivo de Zwaan, for all his help, good and practical advise, patience and revision of my work.

In my personal interpretation of the "architectural" language of these three creators of emotions, I could only end this research with its more obvious conclusion: the image of the perfect musical octave of Borromini's dome, in its simultaneous presence of silence and light.

The most important aspect of Music is the silence, because it is where all tension is created. And in this silence is God.

Regina Albanez next page

Façade of San Carlo alle Quatro Fontane

A similar formal contrast between a rigid structure and one made free by opposition present in the Lamento di Ninfa, can be found in the relation between Maddalena and the Virgin in Caravaggio’s painting, with the juxtaposition of two contrasting forms showed by the outspread body of the Virgin (durus) and Maddalena’s doubled over in a circle (mollis), the curve used as an compositional element with a clear expressive purpose.

In Borromini’s façade for the church of San Carlino, this contrast and the use of the curve for expressive and structural reasons, materializes in many aspects of its formal construction. The two sides corresponding to the two adjacent streets, which limits the whole convent of the Trinitarian order, present a classical structure with prominent sober lines; the "homo-rhythmic" structure of the vertical elements on one side and the decorative elements based on the trinitarian theme of the interior, “tre in uno”, on the other side (first and third section of the lamento, cantato al segno della mano).

The central section, corresponding to the Church’s main entrance and finished thirty years after the conclusion of the interior and lateral facades, is the confluence of this two obliquely plans and can be seen as the interaction of the complexity of the church's interior brought to the exterior, materialized in a theatrical and dramatic gesture (central section, cantato al tempo del animo).

|