Spatial structure

In this sense, the choice of this church fitted perfectly as a structure and guidance to my own thougths, confirmed after my first visit to Rome: the experience of a space materialized in stone and light, which being build upon the human scale simultaneously has the reach of a spiritual revelation.

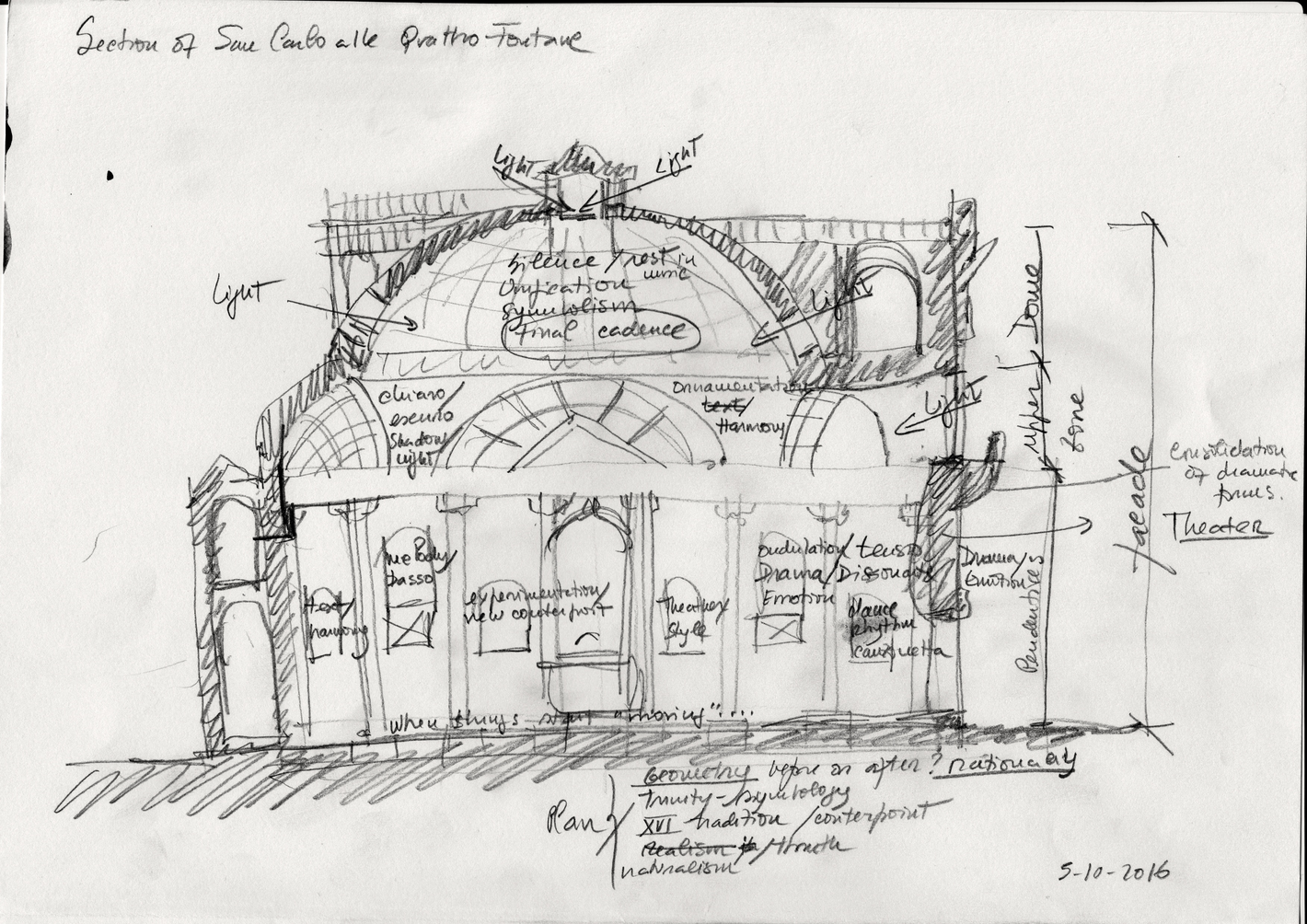

Therefore, used both as structure and source of inspiration, this research will be divided in four parts corresponding to the different levels of Borromini’s church, parts which should be seen interconnected to each other and will be described and related in musical, visual and spatial terms.

Part 1. Plan, Tradition and innovation

Part 2. Transition zone, Contrast and expansion

Part 3. Dome, Illusion and the exploration of the surface

Part 4. Façade, Conclusion

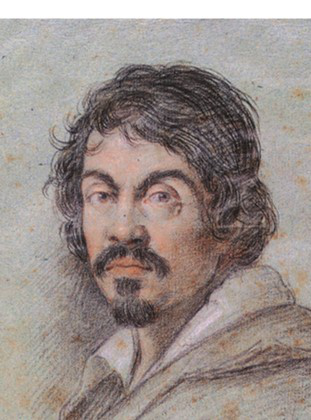

As a visual counterpart to Monteverdi’s work, I have made a selection of Caravaggio paintings from a period starting with the late works of his youth’s naturalistic phase, Maddalena Penittente (1594-5) and Narciso (1597-8) and ending with the major sacred large scale paintings of his Roman period, from which La morte della Virgine (1604-6) can in many ways be seen as his last and most expressive work, before his exile in Naples after 1606.

The order of these paintings is not chronologic but follows the need to illustrate a specific formal or expressive aspect, common to all three artistic forms and is based on my personal impressions during my trips to Rome and Paris, where the selected paintings can be seen.

In this way, departing from the selected musical examples and the related visual/spatial works, I took the liberty to let them lead the way to the development of my ideas; a personal interpretation in many cases following an intuitive approach, without specific restrictions or goals.

That proved to be, in my opinion, both a necessary and fertile decision due to the freedom it opened, from which this research only goal is to be one of many possible interpretations.

Introduction

Knowing that contrasts are what moves our souls, and that such is the aim of all good music- as Boethius asserts: “Music is a part of us, and either ennobles or degrades our behaviour”- I set myself with no little study and zeal to rediscover this style.

With these words from the preface of his eight book of Madrigals, Madrigali Guerrieri et Amorosi from 1638, Claudio Monteverdi was enunciating one of the fundaments of his musical construction, the power of the contrasting passions and emotions. A thirty year journey that started, according to his own words, with the only surviving scena from the opera Arianna from 1607-8, the Lamento d’Arianna.

Following Monteverdi’s progression from this point on, in a method where practice and theory developed together and influenced each other, this research will be centred on the identification of what I called an "Architecture of emotions": a methodical and in many ways experimental construction where tradition and innovation seemed to coexist in equal terms, using the human emotion as an inspirational force and directed to the expression of the human passions.

Borromini and Caravaggio

From the beginning of this research centred in Monteverdi’s music, a different perspective was needed in order to understand the challenges posed not only to the composer but also to painters, poets and architects that lived in the transitional period from late sixteenth- century Renaissance to seventeenth- century Baroque. In this way, looking for a broader view and therefore a more complete picture of the expressive elements I was looking for in the music.

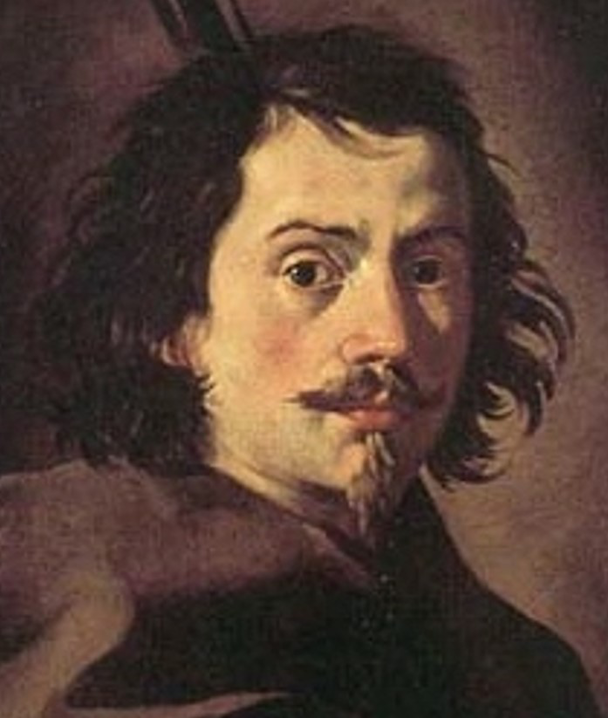

Doing that, two names stood out as the most equivalent visual and spatial counterparts to Monteverdi’s "musical architecture": the painter Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio and the architect Francesco Borromini.

Like Claudio Monteverdi, they were taught and trained in the successful art forms of the humanist background of the sixteenth century, and have felt to some extent, the influence of the traditional artistic language of their common Lombard origins. Also, they all seemed to share the view that innovation could not be fully effective without the examples and impulses of the past, aspects which will be developed in the first part of this research.

Their direct influences reflect this duality between tradition and innovation in their own work. Monteverdi’s teacher Ingegneri, from whom he learned all contrapuntal idiom and the love of a clear, concise structural organization, combined with the progressive styles of Marenzio and Luzzaschi; Caravaggio’s Lombard influences, present in the naturalistic paintings of his youth, and the influences of Barocci and Zuccaro in Rome; Borromini’s formation as a stone mason, the importance of the Gothic legacy felt during his youth working at the cathedral of Milan, followed by the learning years as an architect with his mentor Carlo Madeno at St Peter's Church, combined with his profound admiration of Michelangelo's work in Rome.

The specific demands of a work that was mainly commissioned, either by patronage or the Church, in combination with their methodical and in many ways obsessive personalities, result in a personal language that is bound to the ideals of a common humanist background but simultaneously freed from the conventions tied to the representation of these same ideals. A possible evidence of this, is the approval and influence of their work in their specific fields as well the resistance they all found to their new and in many ways controversial ideas.

As far as it is known, there is no evidence that they ever met or had some sort of contact with each other. However, it seems quite obvious due to the recognition they got, that they knew or heard about each other’s work. Borromini, for example, must have known Caravaggio’s sacred paintings in display throughout several chapels in Rome, being three of his master pieces, the paintings for the Contarelli chapel, in a nearby church of two of Borromini’s important sites, Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza and Sant’Agnese in the Piazza Navona.

A fact is that Caravaggio’s La Morte della Virgine, from 1605-6, was bought by Vicenzo Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua after its rejection by the religious order that commissioned the painting, to join the Duke's art collection when Monteverdi was still employed as his Maestro di Capella. This fact will be further presented in the fourth part of this research.

In part three, another link will be named between the composer and Caravaggio; the influential poet Marino, who they both knew and in some ways admired, as expressed in the gradual importance of Marino’s settings from Monteverdi’s Sixth Book of Madrigals on, or through the direct reference by the poet of Caravaggio's paintings.

One could point out that the differences between each of these artists specific disciplines are larger than those that they share. However, to the advantage of my research, is the setting in a period where a common artistic and cultural background seems to have moved painters, architects, musicians and poets into a common goal, working together in the same environment at the courts of princes, cardinals and private patrons; namely, to pursue a language that could respond to new demands of communication at the level of the human emotions, and could expand its conventional limits through elements of contrast, movement, tension and illusion.

In a broader view, it can be argued that music, can only be perceived in its totality at the very end of its realization and therefore dependent on time, an important factor that does not affect the other two disciplines. However, in my opinion, the perception of architecture as a dynamic and not static experience, is as much dependent on time as music is; a building can only be understood in its totality with the experience of its parts, which implies a specific journey throughout interior and exterior. The "operatic" narratives of Caravaggio's large sacred works, suggest a similar dynamic experience, in order to fully apprehend the narrative itself as well the multiple layers of its symbolic representation.

A complementary aspect of this dynamic perspective, is pointed out by John Varriano in Caravaggio- The art of realism, by the presence of the spectator implied in nearly all Caravaggio's works. According to this author, in paintings approached on the diagonal Caravaggio frequently arranged his figures along structured axes, as well as the effort to unify pictorial and spectatorial space by replicating in most part of his paintings the original sources of light of the places to where they were originally conceived.

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane.

It was the century of triumphant purpose over detail. Particulars where subordinated to a grand whole. The arts were working towards a single end, dominated always by architecture. The architect emerged as the great coordinator.

If I were to choose one work that could illustrate these words by James Lees- Milne and has in its essence the coexistence of elements of change as well as traditional, it would be the first independent commission of Francesco Borromini in Rome, the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane.

Generally considered in art history one of the most important buildings of the Baroque, San Carlino - the way it is known in Rome,- has, in the words of the architect Paolo Portoghesi,"a small scale but all the qualities of great architecture". Borromini’s almost sculptural treatment of space, combine contrasting surfaces, structural and visual continuity between different parts, expansion by means of contrasting curved surfaces of the walls, an illusory perspective upwards and rhythmic variation in both structural and decorative elements. All aspects which I intend to transpose and relate with a selection of Monteverdi’s own musical examples.