Images

The visual expression of Japanese culture.

When we meet a new culture and we open to the unknown worlds, we curiously sharpen our senses. What we find new, exciting or surprising, we try to register with our eyes, ears, the senses of smell, taste and touch. What seems to be familiar we feel a level of comfort with - a homecoming of sorts, as remote as it might be. What we cannot understand, classify or contextualize we are naturally forced to just take in, or maybe rather allow it to absorb us?

The visual dimension of embracing something new seems to me the most immediate form of perception. A picture is registered in the brain in an instant. Just like a sound enters our acoustic awareness. We may understand or not understand what is presented before our eyes, but we are subject to an almost involuntary swift perception leaving us with an aesthetic response, creating a feeling, an emotion. Whatever we experience leaves an impression within.

As we choose to learn more about the cultural context of the artwork viewed, its historical background, the technicalities of the methods used in creating the painting or a woodblock print, the thought accompanying the artist, his or her biography, all these elements contribute to our deeper understanding. This more conscious approach might give us more pleasure of encountering the art the next time, as we can read better between the lines, find new meanings, place what we see in a richer context but also may temporarily peel the layers of mystery away, leaving us with a somewhat bare structure. There are as many options as viewers.

But… if and when we find ourselves in a new place, in a faraway land, without any difficulty, any premeditated effort involved, we let images overwhelm us. The exoticism gets into our visual archive as it imposes itself on our sense of sight. We get pulled into that new scenery just as we may feel tempted to take a careful step back in order to anchor ourselves in the safety of our cultural background. Both processes happen quite involuntarily and can be simultaneous.

Visual art, just like music has the power to communicate in an immediate manner. And as we either welcome that new impression, fall for it, feel drawn to view again or reject; as we try to understand consciously what triggered our response of attraction or dislike: the seeing is done. Directly. Just like with the music we have just heard: the hearing is done at that very moment. It can never be un-done, reversed.

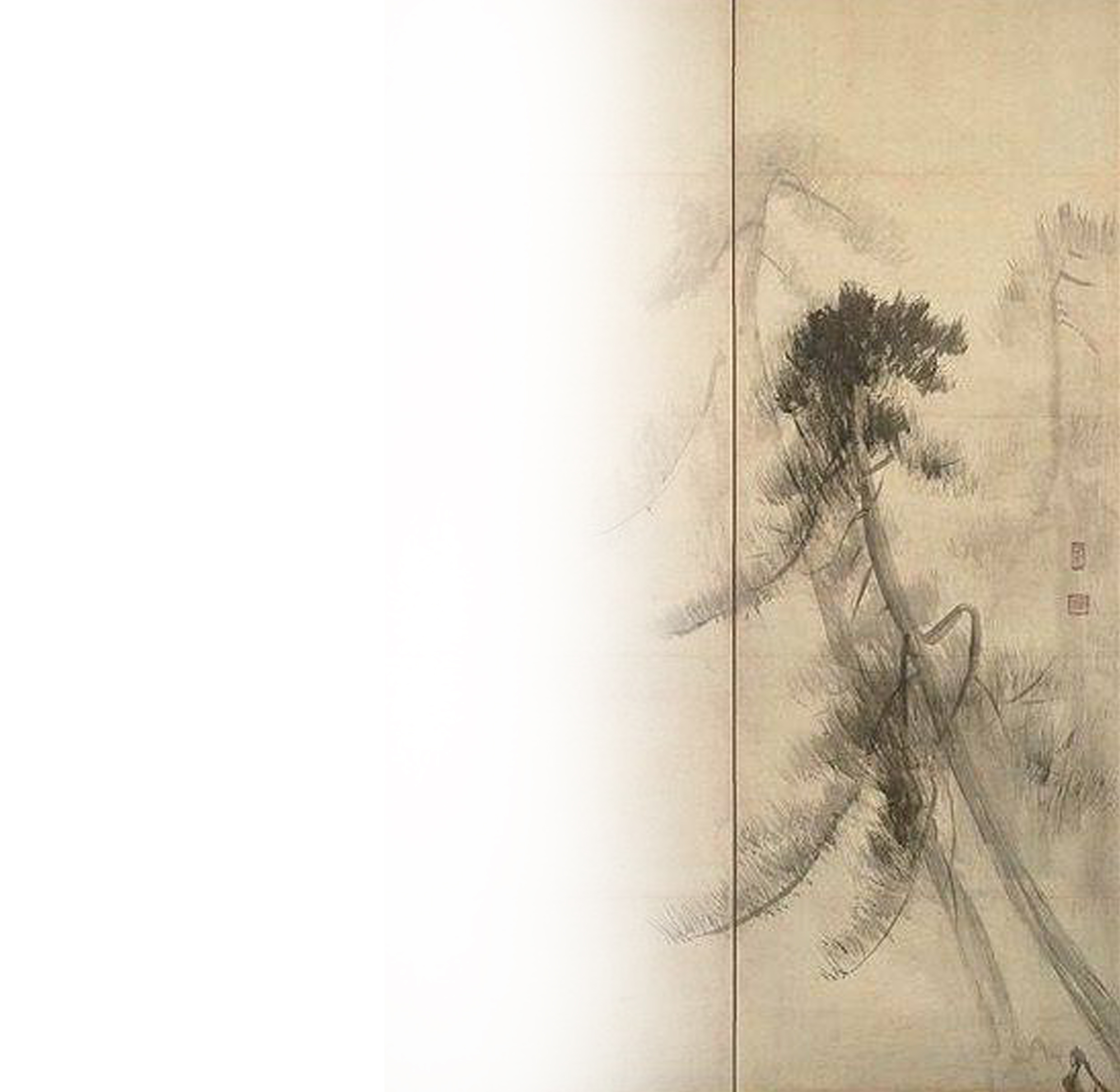

It is my impression, that master painters and calligraphers of the past were acutely aware of the impact that an image might have on their highly imagery sensitized audience. And they used that knowledge in bringing their art closer to the public, serving, amongst others, the most common appreciation: for the natural world. Nature became a medium of their message. It happened in many forms: in decorating of objects or design of textiles, in paintings of seasonal subjects; four-season paintings shiki-e, twelve- month painting tsukinami-e.

“The manner in which the seasonal associations of waka, particularly those of flowers and plants, permeated Heian aristocratic culture is perhaps most dramatically demonstrated in the design and colours of the woman’s multi-layered kimono now referred to as the (…) twelve- layered dress. Each layer of the robe had a specific colour combination, appropriate to each season” 2.1

“In the Heian period, aristocrats not only “wore“ the seasons, but were surrounded by waka- based seasonal references inside their palace-style residences.” 2.2

So, if the culture is so sensitive to the visual stimuli that it perpetually seeks various platforms to express it, why should I not look for imagery element in the poem itself? Or... should I rather look for poetry in the image?