This research project investigates how a speculative approach to scientific/mathematical models of physical dimensions and their interrelationships can be used as a generative tool in contemporary art. The exploration is situated within a cross-disciplinary arena that incorporates artistic strategies from New Media Art, Interactive Installation, and Performance, merging them into an expanded and interconnected site that I have chosen to call a “performative installation”. Throughout, I engage with formal, digital, narrative, and interactive practices to investigate how speculative fabulation and interdimensional movement can work as reflective tools within these performative installations.

The narrative and digital installation-based structures in the performative installation constitute the mediums from which one can explore movement between various dimensionalities: from the very concrete one (line), two (plane), and three-dimensional (space), to the more complex, expanded dimensionalities of Hyperspace. [1] These geometrical modulations in experiencing and sensing point towards possibilities for physical embodiment and movement in the space of the artwork, which are entangled with movements in thinking and imagination. Here, the research project explores a methodology of interdimensional artistic speculation designed to traverse established aesthetic, formal, and conceptual boundaries, and in turn, possibly offer a way to reflect more broadly.

The digital object to the right renders an approximation of a four-dimensional cube, a Hypercube. If a fourth spatial dimension exists, we cannot experience it from the perspective of our three-dimensional constitution. It occurs in theoretical physics, as a mathematical possibility, and in speculative fiction as a potential of being embedded in something beyond our senses. [2] We can only seem to grasp a fragmented approximation. The avant-garde explored various possibilities of depicting this impossible, hidden, extradimensional perspective throughout the first half of the 20th century. [3] I am interested in dialoguing with this history and exploring how to work with hyperspace as a contemporary artist. Especially now, as our physical selves merge with the virtual information sphere and we navigate the complex, unseen fabric of today’s physical-digital entanglements.

So, I look at this 3D computer rendition of the fourth spatial dimension. It uses movement and change to point towards the inaccessible, making the cube fold into itself, so that the central cube becomes the surrounding one, and back, repeatedly. I look at it. I meditate on it. I speculate on how to make the PhD work into an artistic space — a “performative installation”, an entangled perspective, operating exactly like this. And because it is an impossible space/perspective I want to reach, I return to the attempt again and again in my artistic research, much like the folding hypercube itself.

In this return, I can identify that my artistic practice and research gravitate towards articulating a related folding of subject and object: a place where the surroundings become the central agent, where an individual becomes a network or context, where the artist becomes the artwork, or the audience becomes the generators of art. [4]

As such, the project is curious about how things are interconnected. How do we put ourselves in an active, entangled relation to that which is both within and beyond our reach? Can a hyperspatial perspective be a way to reflect on our contemporary hybrid, networked, complex lives? How can that be done? Who or what is it that does that reflection? Why is this important?

Why is this important? Behind and around all our activities as humans—as family members, professionals, artists, academics, going about our very important daily activities—there are a range of interconnected crises brewing, imploring us to respond: Our climate cannot sustain the human-made waste anymore, biodiversity is plummeting, pandemic waves flow through human/animal biologies, socioeconomic inequality is increasing, and democratic mechanisms are eroding. Our responses, both on an individual level and through the constructed nation-states and institutions of the western, international community, seem staggeringly inadequate. How, then, is it possible to respond?

This project suggests that we need to find a way of thinking and experiencing differently, a way of moving out of fixed worldviews – or, as Donna Haraway says, it is most pressing that “we invent new practices of imagination, resistance, revolt, repair, and mourning". [5]

How then, is it possible for the performative installations to heed this call for new practices of imagination?

Initially, the project suggests that engagement with expanded dimensions can place us at the edge of the known and invite us to relate to what lies beyond our cognitive or perceptual scopes. Instead of negating or othering, we might connect, even without fully comprehending or owning it in our understanding. In this way, the project aims to offer a reflective tool for exploring how we relate as part of our environment, which is complex and entangled between the physical, virtual, technological, and biological realms.

ENTANGLED MIND

To substantiate this approach, I have drawn on the network perspectives of new-materialist and object-oriented thinkers such as Haraway, Karen Barad and Bruno Latour. However, what helps me grasp this best and historically situate the thinking is how cybernetics thinker Gregory Bateson discussed the concept of Mind in the 1970s. [6] Bateson repeatedly emphasised that our epistemological view is skewed and that this is detrimental to both the climate and social equality. He suggested that the problem lies in how we view the relationship between organism and environment. He proposed a larger mind, a basic cybernetic unit, that transcends the body of the organism, which he called “organism-plus-environment”. [7] You cannot explain any behaviour by drawing the line by the human alone. The mind or consciousness at work in any situation must encompass all the elements that contribute to a particular behaviour. A famous illustration of this idea, introduced by Bateson, is the image of a blind person and their walking stick. To explain the action of the blind person walking, you would need to include the street - the stick - the arm of the person - the brain of the person - the feet of the person - the street - the stick - the arm - the brain - the feet, and so on, in an ongoing loop. [8]

I have been exploring this cybernetic approach as a playful, speculative practice. When I write this text on the computer, I attempt to be aware of the mind that encompasses the table - the laptop hard drive and processor - the laptop screen - the keyboard - the fingers writing - the arms - the eyes - the brain - the back - the chair - the table - the laptop hard drive and processor - the laptop screen - the keyboard - and so on. When the activity changes, so does the mind that is involved, leading to a shifting, expanded, entangled way of being.

Bateson suggests that our default as humans might be to align individual, subjective agency with the need for a neutral, objective position; a feeling of being separate and distant from our surroundings. We think we need to have a completely conscious, rational overview to respond adequately, or that such a “conscious purpose” [9] is even possible. Bateson argues that, since this might not be how things are, the output of our otherwise well-intended actions ends up being different from what we anticipated, even quite detrimental. If we are, in fact, an entangled part of the world, we have to actively relate to what we do not have a conscious overview of. In one way, decentralising the importance of our conscious, rational brain as only a small element in Mind, and in another way, expanding ourselves to include blind spots and half-perceptions. A subconscious outside of the body, instead of a psychoanalytically internalised one. [10] As this project suggests, it is a bit like being in this hypercube, folding into an invisible dimension, or as close to it as can be.

A curious thing that Bateson often repeats in his transcribed speeches is that, even though he can lecture about this “organism-plus-environment” as the smallest unit of Mind, he still feels separated from his audience, aware of himself as a singular person on a podium. Likewise, I experience that this entangled position rings true, yet still feels impossible to fully embody, at least rationally. But what about aesthetically?

This project proposes that one response can be a speculative, imaginative, embodied artistic methodology that is not fixed but constantly moving towards, within a field of paradoxes and contradictions, shifting between the virtual and the embodied. Moving towards or attuning ourselves to this ‘impossible’ way of experiencing our position/constitution might have the potential to influence how we reflect and thus change how we act. There might at least be potential for a more embodied, insightful reflection on where we divide and cut our consciousness and the world. We might become more response-able, as Donna Haraway would put it. [11] This is what I wish to invite the audiences and participants into when entering the performative installations.

And here we come to the question of how this can be done through artistic research specifically.

While mediating my artistic research project, I attempt to communicate transparently and generously, without cutting and isolating areas in a way I find counter to the premise of the project. On a fundamental level, the project assumes that our spatial and mental perspectives are connected: that the way we are embodied and embedded in time and space is entangled with our understanding and ability to reflect. We understand the world through our physical embeddedness, and vice versa. When we perceive the way in which we are embedded differently, this might also change our thoughts and actions. Additionally, if we find ourselves in a new material/digital/biological/spatial constellation, this will, in turn, affect how we perceive the way we are embedded. This is why an artistic research project that builds physical environments, worlds, and experiences might offer something complementary to a purely theoretical proposition in academic research.

INTERDIMENSIONAL ARTISTIC SPECULATION

I suggest that the formal, aesthetic interdimensional exploration in modernism, which I draw on and develop, can be formulated as a type of expanded, speculative movement through the spatial, digital, and narrative media of the performative installations. To develop a methodological map that thoroughly accounts for how I engage with speculation, as well as to be more suited to a contemporary, expanded media project, I have included the method of SF / Speculative Fabulation and entangled it with interdimensional movement. Together, they make up the methodology of INTERDIMENSIONAL ARTISTIC SPECULATION.

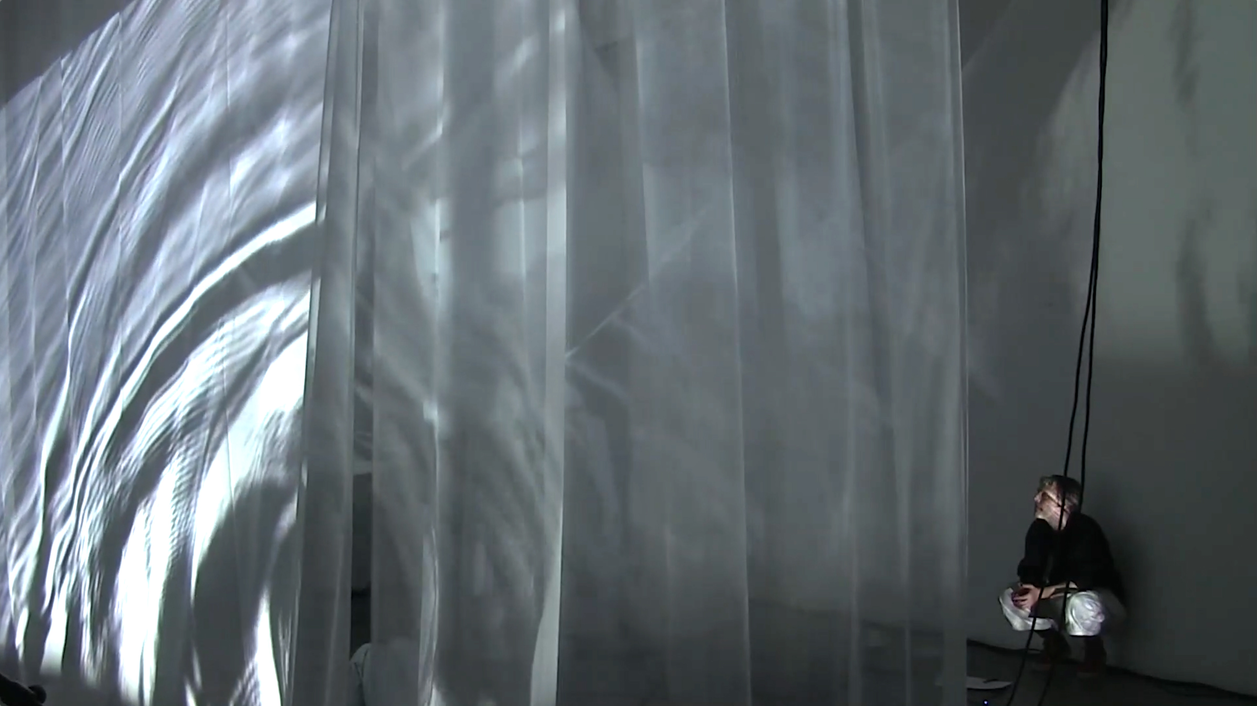

SF: Speculative Fabulation / Science Fiction / Science Fact / String Figuring, as articulated by Donna Haraway, mainly accounts for how speculative / imaginative practices merge across the scientific and aesthetic realms. Literary theorist Robert Scholes articulated Speculative Fabulation to account for how narratives in speculative fiction balance the realistic or cognitive with the imaginative, thus stimulating reflection on the actual world. He also describes how aesthetic literary realms become co-productive in relation to the actual world they speculate on. [12] Thus, SF has helped me to substantiate my engagement with interdimensional artistic speculation and clarify how the project traverses the imaginative with the actual, moving through narrative topologies as well as spatial ones. As such, the interdimensional artistic speculation occurring through the performative installations comprises both an artistic research methodology and an artistic research site. It is a performative, shifting installation created through interlinked constellations of various artistic media. These include immersive architecture, tactile materials like rope and fabric, human bodily movement, and narrative gestures through monologue, conversation, and role play. It also involves interactive and augmented digital dynamics, using sensors, visual programming, video projection, lights, motors, and speakers.

At times, this speculative interdimensional movement occurs very literally through the consideration of elements in the installation, such as 1D lines/ropes, 2D planes/projection screens, as well as space and time via movement and distance within the installations. At other times, the performative installations fold into expanded hyper-dimensions. This project suggests that this can be achieved through digital augmentation: The digital, interactive setup makes the space perform in a layered and expansive way, where it acts and moves beyond the normative limits of gravity, temporality, and spatiality. This has the effect of making participants and audiences shift between feeling materially embodied in the concrete space and feeling as if they are in a virtual, abstracted, almost internalised space. Additionally, the project proposes that the performative installation can achieve this hyperspatial folding through speculative text or narrative: Here, the movement between perspectives occurs through different speculative fabulations or embodiments, suggested via narratives and concepts during the performance. For example, suggestions might include entering the linear dimension of a rope, becoming a flat shadow, or transforming into an expanded more-than-human entity.

Following on from the premise of interconnection: The fact that the project is situated in a post-60s expanded field of cross-disciplinary practices is integral, constructing the performative installations as a multi-media mesh that weaves Installation, New Media, Performance, and Text into one another. As such, the participants are invited into shifting relationships with the media modulations of the work. Another way to articulate this is to say that they are invited to move between various perspectives or dimensionalities. At points, they are even invited to move further into complex, expanded dimensionalities that are “strange,” “half-hidden” or “impossible”. All combined, this forms the speculative, hyperspatial folding space of the performative installation.

MORE-THAN-HUMAN-BEINGS

In this intermedial and interdimensional folding, where the roles of subject and surroundings, artwork and viewer shift, a more expanded perspective has emerged through the developmental inquiry: Can the performative installation be encountered as an entangled, more-than-human body/mind? [13] And, in turn, what might the body and voice of the more-than-human tell us humans about how we construct identities, subjectivities, and concepts, and about how we divide and cut our consciousness and the world? If we are in a paradigm shift that seeks to consider the "perspective of the larger cybernetic Mind" and move beyond a mere negation or instrumentalisation of the more-than-human, surely the consequence must be more than just being “nice to nature”. If we are to consider the "voices of the more-than-human", we must explore what it takes to listen, how to connect, and expand on what these voices and conversations really are. We must also be open to aligning the workings of life and society with these expanded, networked modalities.

Concurrent with this, the project has increasingly focused on a new-materialist notion of how to give voice to interdimensional/intermedial performative installations, speculatively transforming them into larger environment beings that talk and express themselves through the media modalities of the work. The artistic results have therefore taken the form of actual speculative fabulations: a series of larger more-than-human beings that the audience can become part of and listen to from within. These include “Marie Sikveland as a Room”, “Store Lungegårdsvannet”, “The Art Academy”, and the “Earth Being of Nordnes” in Bergen.

As such, the artistic research project might hold a layered reflective potential, extending through all levels of the work. This includes the artistic researcher, the participants and performers, as well as broader new-materialist-type agencies. This type of reflection is aesthetic, embodied, expanded, distributed, and transgressive. It might explore how to stretch the mind and imagination and, in turn, examine how much one can stretch in relation to one’s surroundings.

Here, the role of the artist and researcher might also expand and decentralise, transforming into that of an interpreter and mediator of the artistic research. This could be argued to be the way all artistic research is, or should be, conducted: research through the art. [14]

SUMMARY OF CHAPTER

This chapter lays out the key inquiries of the PhD, specifically how a speculative approach to scientific and mathematical models of physical dimensions and their interrelationships can serve as a generative tool in artistic research, inviting more expanded and entangled ways of reflecting.

The project contextually engages with early 20th-century modernist explorations of a fourth-dimensional space, or hyperspace. The chapter explains how this served as a starting point for developing a more expanded methodology of INTERDIMENSIONAL ARTISTIC SPECULATION as a contemporary artistic approach, and shows how this methodology has been engaged within an intermedial arena of PERFORMATIVE INSTALLATIONS.

Finally, the chapter elaborates on how this development has led to transgressive formal and reflective folds in the artworks, which in turn raise a new materialist question of how the performative installations can transform into MORE-THAN-HUMAN BEINGS that express themselves through the media of the work. The artistic results have thus taken the form of speculative fabulations—larger environmental beings with whom the audience can engage and listen to from within.

- PhD Candidate: Sidsel Christensen

- Project title: INTERDIMENSIONAL ARTISTIC REFLECTION: Speculative movements through Spatial, Digital and Narrative Media

- Host institution: The Art Academy – Department of Contemporary Art, Faculty of Art, Music and Design, University of Bergen

- PhD supervisors: Brandon LaBelle, Frans Jacobi and Sher Doruff

[1] The term "Hyperspace" is used in the popular presentation of theoretical physics where quantum mechanics meets general relativity, such as in String Theory and M-theory, to describe dimensions beyond the four of space-time. It is also employed in speculative science fiction to depict parallel hidden dimensions and faster-than-light travel. I am interested in using this term because its application spans both science and science fiction. However, throughout the reflection I also use the terms extra-dimensional and expanded dimensions to refer to dimensions beyond the space-time we can perceive.

[2] Unlike the fourth temporal dimension of space-time, which was established as scientifically real when Albert Einstein’s theory of General Relativity (1915) was proven in 1919 by the observation of light bending around a solar eclipse.

[3] One central source of this historical mapping is from art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson. She mentions artists working with the fourth dimension all the way back to early abstraction, for example Kandinsky, and that the idea greatly impacted the development of cubism and suprematist abstraction, through the art of Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, Picasso, Malevich, as well as in the art of Marcel Duchamp. In 1936, Hungarian artist and poet Charles Tamkó Sirato wrote the “Dimensionist” manifesto in Paris, and got many leading avant-garde artists to sign it, amongst others Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Francis Picabia, Kandinsky, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró, and László Moholy-Nagy.

Linda Dalrymple Henderson, "The Image and Imagination of the Fourth Dimension in Twentieth-Century Art and Culture" (paper presented at the conference "The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art," Princeton University, 2009)

[4] This tendency might not be a unique quality of my approach but rather an integral part of the historic, medium-specific context from which I work as an artist. I see my own intermedial art practice as a natural continuation of the questions and strategies developed through the expanded practices of the 1960s onwards. Following philosopher Josefine Wikström’s critical concept of performance in her book Practices of Relations in Task-Dance and The Event-Score (2020), where she aligns this period of dematerialisation and the breakdown of medium-specific boundaries in art with the development of modernity and the history of philosophy, I am interested in exploring this perspective. I look at how the breakdown of boundaries between art, audience, artist, context, and content was a material, aesthetic way to reflect the philosophical subject-object questions in broader thinking. I will elaborate on this in the chapters “Conversations with The Field” and “Performative Installations as Multimedia Sites”.

[5] Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 51.

[6] “If you want to explain or understand anything in human behaviour, you are always dealing with total circuits, completed circuits. This is the elementary cybernetic thought.” Gregory Bateson, "Form, Substance, and Difference," 1970, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind (The University of Chicago Press, 1972), 465.

[7] Gregory Bateson, "Form, Substance, and Difference," 1970, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind (The University of Chicago Press, 1972), 455.

[8] Gregory Bateson, "Form, Substance, and Difference," 1970, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind (The University of Chicago Press, 1972), 465.

[9] Gregory Bateson, "Form, Substance, and Difference," 1970, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind (The University of Chicago Press, 1972), 439.

[10] The externalised subconscious is a reflection achieved through practising "organism-plus-environment", but Bateson also discusses it, so it is by no means original. He writes, "The individual mind is imminent not only in the body but also in pathways and messages outside the body; and there is a larger Mind of which the individual mind is only a subsystem.”

Gregory Bateson, "Form, Substance, and Difference," 1970, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind (The University of Chicago Press, 1972), 467.

[11] Donna J. Haraway, Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 2.

[12] I will reference and elaborate on Donna Haraway’s ideas in the chapter “Conversations with the Field” and on Robert Sholes’s theories in the chapter “Interdimensional Artistic Speculation”.

[13] In 1996 ecologist and philosopher David Abram coined the phrase "the more-than-human world" as a way of referring to earthly nature. Now the term more-than-human is often used by scholars to include a wider range of forms, from the natural and biological to the mechanical and digital. I follow this more expanded terminology in this project.

David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (New York: Pantheon Books, 1996).

Marek Tamm and Zoltán Boldizsár Simon, "More-Than-Human History: Philosophy of History at the Time of the Anthropocene," in *Philosophy of History: Twenty-First-Century Perspectives*, ed. Jouni-Matti Kuukkanen (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 203.

[14] Professor Hendrik Anne Borgdorff defines research through the art, saying “We can justifiably speak of artistic research (‘research in the arts’) when that artistic practice is not only the result of the research, but also its methodological vehicle, when the research unfolds in and through the acts of creating and performing. This is a distinguishing feature of this research type within the whole of academic research». I position this PhD project in line with this definition, and also explore the edges of this framework throughout this reflection.

Hendrik Anne Borgdorff, The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012), 147.

Credits: All material, technical and documentation work of the PhD has been done together with Sidsel Christensen. Where no name is mentioned in credits, Sidsel has done the work or documentation.

From development of the artistic result "The Panel Discussion of Another Dimension"

Documentation by Sofie Hviid Vinther.