I do most of my work in a studio. It’s hard for me to work anywhere else, because my studio has everything I need: work-tables, chairs, a computer, pens, paper, a kettle, cups, and books. My work tends to be a combination of planned and intuitive activities. During the planned parts, I work towards clear goals: I send emails, do admin, draw, create prototypes, arrange events, design and plan publications, etc. When I work more intuitively, I don’t necessarily do different things; I do, however, work at a different pace. Slower, in a more exploratory way.

My mind is quietly whirring in the background while my body carries out practical tasks. Donald Schön’s writings reinforce my belief that the creative process is inherently complex. It involves numerous variables, potential combinations, and final outcomes. What makes things so intriguing is that the artistic result will thoughtfully represent all these choices in a distinctly visible way (1991, 79). The materialisation of the artistic outcome can be traced back to work the artist did in their studio. My own studio, for example, contains the artifacts I used in the Inner Political Landscapes workshop. It is a space for collecting material and processing ideas.

The most important objects in my studio are the walls, especially one in particular. I tend to talk to this wall and with the material that is attached to it. The book Discursive Design contains a very broad definition of the word ‘discourse’:

Discourses are composed by ideas, values, attitudes, and beliefs that are, as mentioned above, manifested through various forms of writing, speaking, gesturing, and acting through objects and technologies (Tharp and Tharp 2018, 76).

My wall dialogue started early on in my project. My first studio was long and narrow, with one wall measuring more than seven metres. There was a window with a view: I could see the cemetery, whose trees are pruned in a way that calls to mind the sylvan silhouettes on the hills surrounding Rome. It’s a view that made me want to daydream, to escape into fantasy. I first realised how important my dialogue with this wall was when I was asked to write about my PhD work (Rundberg 2020) for Ymt, an annual magazine put together by Visual Communication Design students at the Department of Design. Ymt is part of a research-based teaching course in Editorial Design. The title of the article I wrote was ‘All I have to do and (almost) everything I have done so far: First 6 months’.

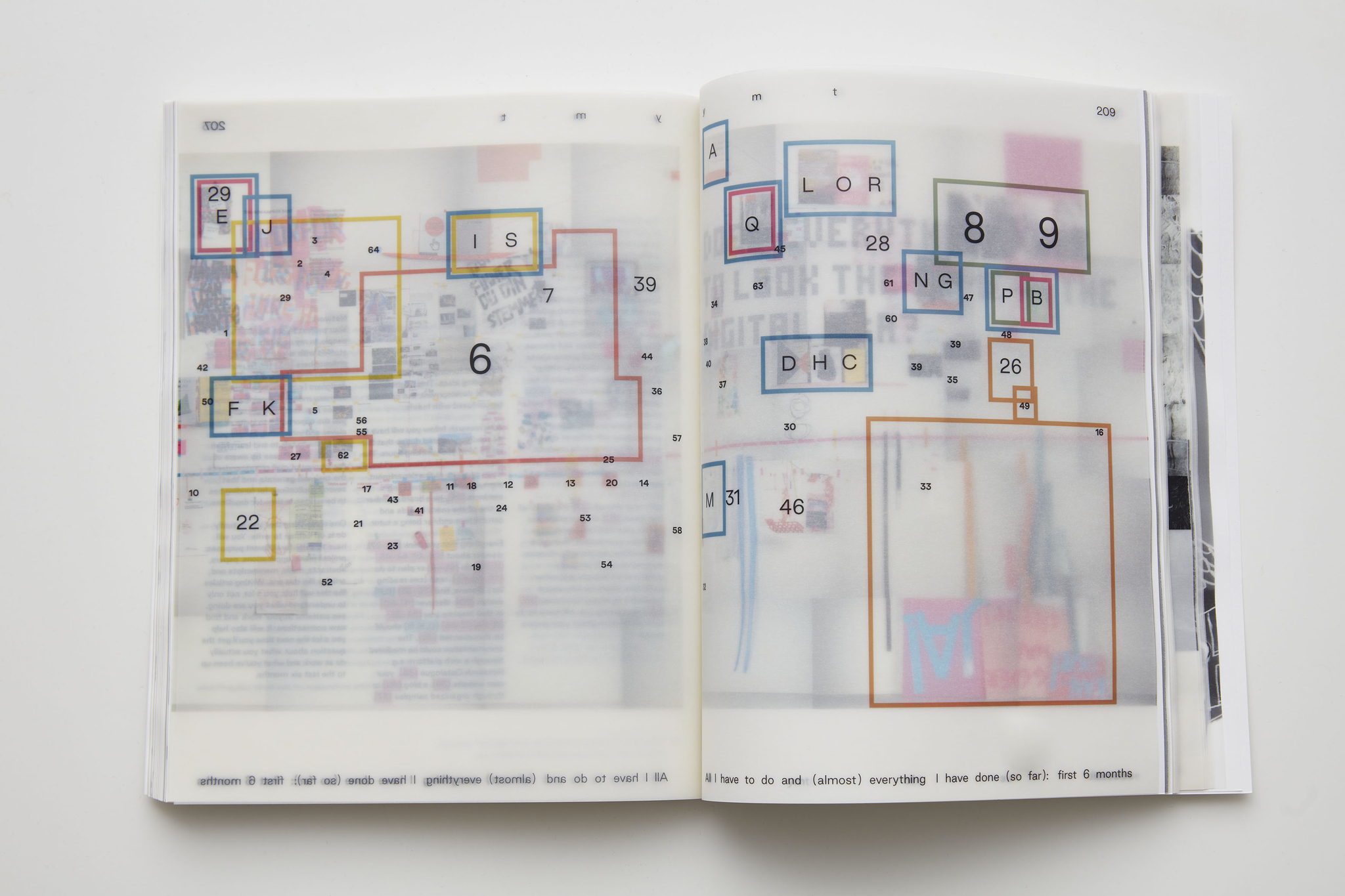

Vilde Valland and Caroline Thanh Tran, two students, photographed and documented (fig. 2.1) the wall for the magazine, while I wrote the actual article. For the article’s accompanying image, I designed a matrix that was printed onto the image of the wall, where the research material was grouped, numbered, and sorted. The magazine was beautifully designed by the students in the course, and printed on transparent paper (fig. 2.2-13), which made the images and the text blend into each other.

The image that accompanied the article became a starting point for me to continue my conversation with the wall—with my notes, objects, papers, books, shelves, hand-drawn diagrams, strings, tape, etc. The wall’s main element was a timeline, with a one-month mark every ten centimetres. I often think about Karel Martens and his walls. This Dutch designer, born in 1939, also seems to have a lot of things in his studio. He’s a collector of things, of trinkets. Portraits of him are often taken in his studio, against the backdrop of his infamous walls. Martens has made a short film (Martens 2000) about the walls of his studio,4 with still images cut into sequences. The camera zooms in and out of old news-paper clippings, bits of plastic, colour swatches, print proofs, paper bags, patterns. A drum beats in the background. Just like I do, Martens engages in dialogue with his walls and his things. He thinks about shapes, collects items. By sharing his wall-work with us, he invites us to participate in his art—a process that leaves me feeling awestruck.

The walls in my own studio (both the one I occupy now and the ones I worked from earlier on in the project) serve multiple functions. They allow me to organise my material and make sense of work through visual communication (fig. 2.14).

I am reminded of things that are out of sight, things that have disappeared into the periphery. Everything is visible at all times. I can search for things even when I’m not quite sure what I’m looking for. During my PhD project, my tutors monitored my process: I had put up portraits of them on the wall. The dialogical process helps me understand themes, contexts, situations. What have I come across here? What is the common denominator between, say, a small sculpture of a state archive and a plastic snack-bar fork? Donald Schön describes ‘reflection-in-action’:

He [the designer] shapes the situation, in accordance with his initial appreciation of it, the situation ‘talks back’, and he responds to the situation’s back-talk (1991, 79).

The walls are a filter through which a project is repeatedly refined. Over the course of my project, I had three different studios. Multiple documentations of these studios’ walls are stored in the Research Catalogue.5 These photos and photo montages clearly illustrate the hermeneutical process within my project: they demonstrate that my view was never static.

The first image I uploaded to the Research Catalogue (Rundberg 2019b) was the one used for Ymt magazine. The Research Catalogue process page (Rundberg 2022) allowed me to digitally continue my wall dialogue, even when I moved to a new studio. The archived digital versions of the walls offered me a different perspective on what I was doing, which can be difficult to achieve in an actual studio in real life. Digitalisation creates distance. I could suddenly compare previous versions of previous walls with the wall of the studio I occupied that day. When I scrolled back through these past images, I could see that some of my wall’s Post-it notes had been with me from day one, for example. The entire process was clearly ambiguous, and rarely logical or linear.

The artistic work conducted during this study fits into different categories:

The studio (as a whole), the wall—a -dialogue between me, the analogue and the digital, and an outward-oriented practice.

To further delve into the Research Catalogue process page—take a look here.