Carl Reinecke arranged Mozart's piano concert No.26 K.537, 2nd movement “Larghetto”1 and his own performance was preserved on a Welte-Mignon piano roll in 1905 when he

was already 80 years old (Audio 5). “On first listening, some of his modifications have the aural effect of lurching and erratic surging,”2 Peres Da Costa wrote about his first impression

of listening to Reinecke's performance of his arrangement of K.537 “Larghetto”. On this roll, there are plenty of examples of dislocations, arpeggiations, and various types of rubatos.

We discover many more things if we compare it to what he wrote down in his score. The differences between the two are quite significant; Malcolm Bilson said in the lecture video

Knowing the Score: “The interesting [thing] is not how he played, but how he did write it down”.3

1. Carl Reinecke. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Andante aus dem Klavierkonzert A-Dur KV.488, Larghetto aus dem Klavierkonzert D-Dur KV.537 “Krönungskonzert” reprinted, Leipzig: Reinecke Musikverlag, 2008.

2. Peres Da Costa, Off the Record: Performing Practices in Romantic Piano Playing, 269.

3. Malcolm Bilson, “Knowing the Score”, 57:36. https://youtu.be/mVGN_YAX03A?feature=shared&t=3456

Chapter 3: "Larghetto" from Mozart Piano Concerto No.26, K.537, as Interpreted by Reinecke

3.2 Reinecke's Arrangement "Larghetto" for Solo Piano and His Recording

table (名) 仕事台、表、テーブル

table (動) 棚上げする、遅らせる、延期する、先送りする

table of contents (名) 内容、中身、目次

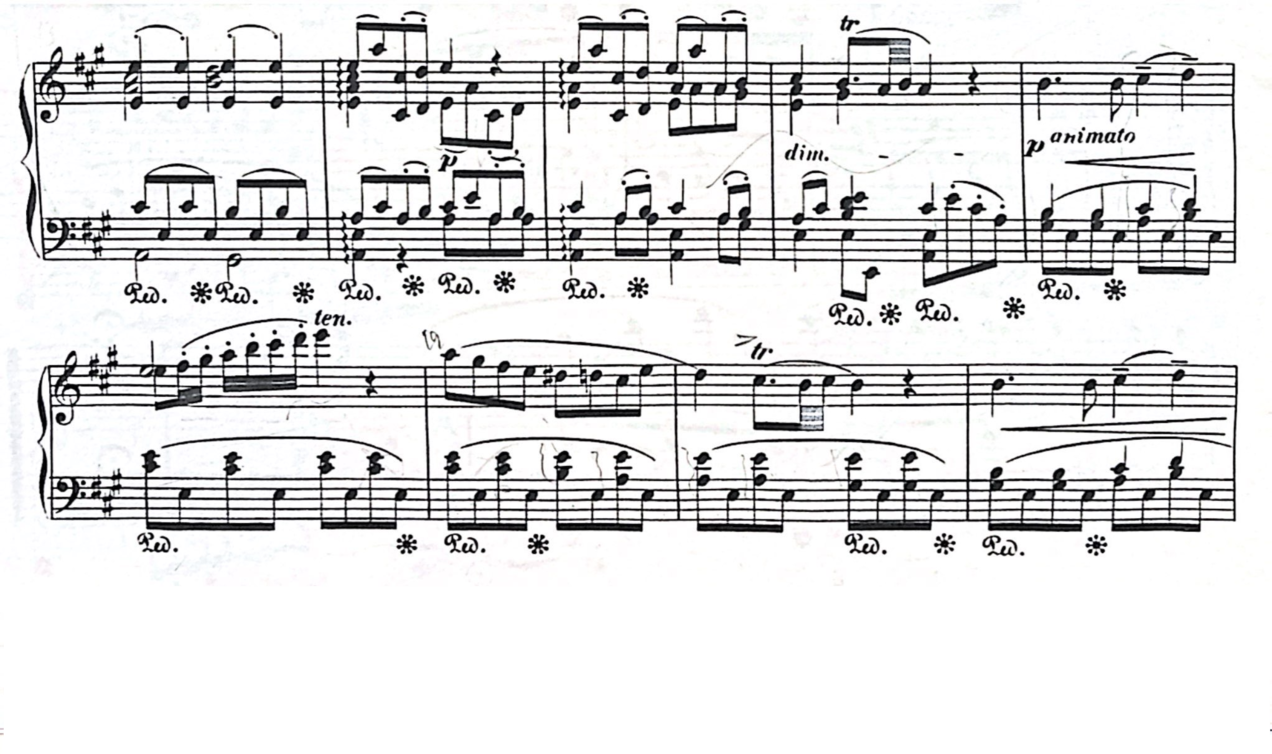

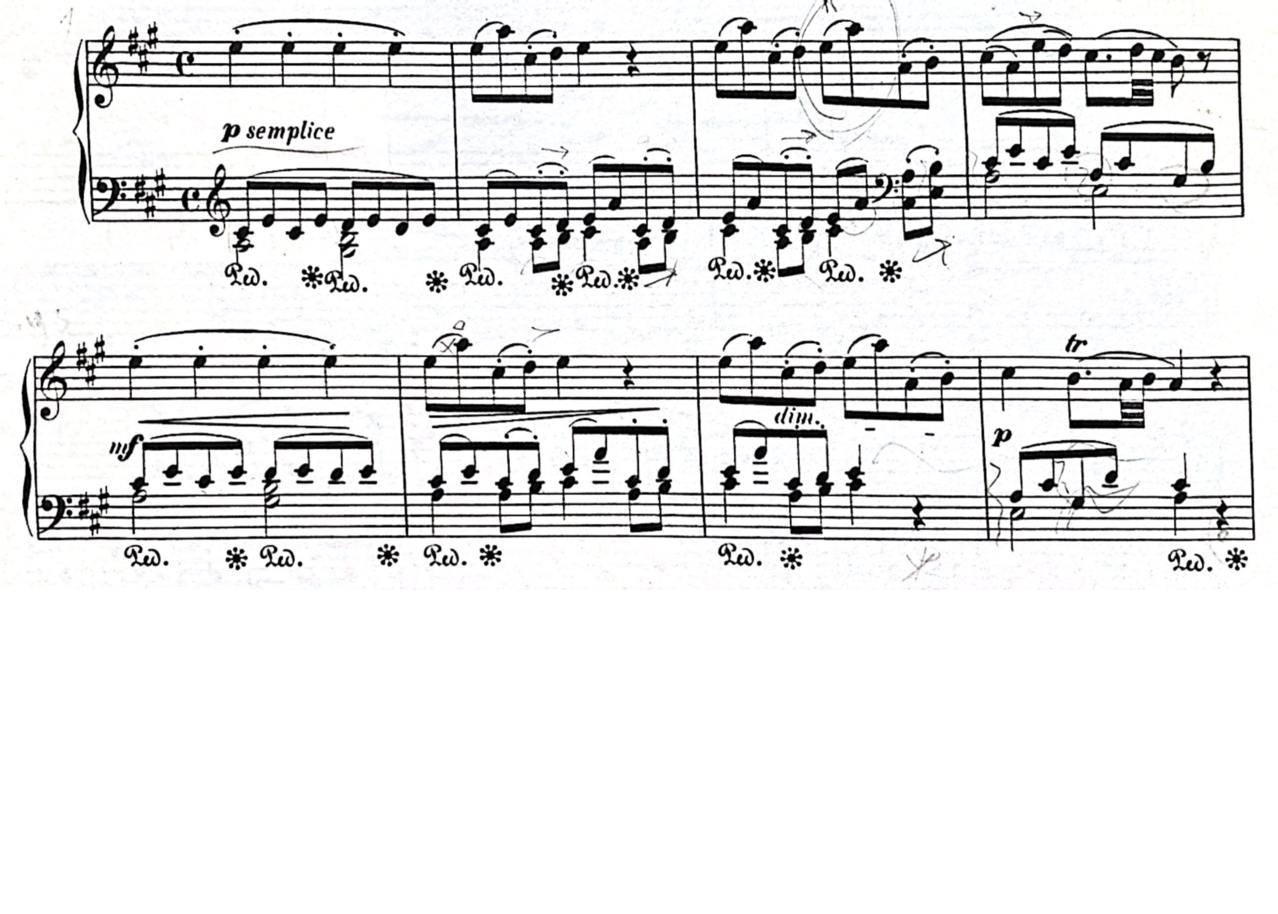

Bars 13-30 from Mozart’s piano concerto No.26 K.537 Larghetto, arranged by Carl Reinecke

Also, please note that Reinecke skipped bars 8-16 in the recording.

The first thing that strikes me is the vertical misalignment of notes, which can be heard

throughout the performance: it is relatively rare to find a place where the vertical material

is perfectly together. The chords in the left-hand accompaniment are not played simultaneously

but rather with an unnotated arpeggiation. The first four quarter notes “E” in the right hand have

added portato notation, which is not present in the original, and these are played with even

more delay than the arpeggios in the left hand, following the practices of the 19th-century we

saw in the previous chapter. In the figures "E-A-C#-D" that appear alternately in the left and right

hands in bars 2 and 3, we can hear the earlier rubato—the slur on the first two notes, "E-A"

extends the first note "E" longer than its value each time, and the portato on the third and

fourth “C#-D” pushes it forward to create the direction to the first beat of the next bars. The

alternating appearance of rubato on the figures creates dislocations between the left and right

hands, which in turn creates a kind of musical tension despite the gradual impression. The

extent of the rubato also changes, with each repeated figure having the high points in the

phrase more expressive and emphasized. However, during those moments, the left-hand

arpeggios and the dislocation between both hands—which is different from the earlier rubato—

always continue, so it is difficult to hear what effects such vertical displacements are having just

by listening the first time.

The question then arises about the “semplice” indication Reinecke added at the beginning of

the movement. Indeed, this movement has simplicity in its melody, chords, and form that

is appropriate for this term, but to our modern ears, his performance is far from simple; instead,

it sounds rather expressive and sometimes chaotic. For Reinecke, such dislocation,

unnotated arpeggios, and rubato not found in the score clearly did not contradict “semplice”.

If we analyze Reinecke’s work in detail, we can find many such examples of how he

actually used the freedom-making ingredients discussed in the previous chapter (dislocation,

unnotated arpeggios, early or late types of rubato). In general, it is surprising how

abundantly he interweaves these elements into his performance. The result gives us the

expressive, chaotic, tolerant and intimate impression, in keeping with the word “Larghetto” and

different from the clean, innocent performance of Mozart we are used to hearing today. He also

seems to have succeeded in creating musical impetus and tension in the relaxed atmosphere.

Including the note-inégals, the earlier rubato gives the melody the impression that he is saying

something sincere. The gap between the two hands is mainly the result of dislocation

and unwritten arpeggios rather than coming from the independence of each hand. The

significant gap between his playing and the notation is almost shocking. The fact that he used so

many unwritten arpeggios, dislocations, and rubato in his performance of the pieces he arranged

clearly indicates that, for him, these performance practices were tacit knowledge and things not

to be visually notated in the score.

The “animato” added in bar 17 seems to be his written indication of a tempo modification.

Here, he has increased the tempo to give the music more thrust in his performance. From bar 18,

he plays the left-hand accompaniment differently to the recording from his score to partly

repeated single “E” notes, contrasting with the arpeggiated chords in the left hand in earlier

sections. This change supported the running up 16th notes figure in the right hand and made the

music forward. In some eighth or sixteenthnote passages in bars 19, 23 and 25, he plays them as

in note-inégals.

The “un poco slentando” in bar 27 is also understandable as a written tempo modification

(the same as with the “animato” in bar 17), and Reinecke indeed slows down there a bit. However,

he regularly relaxes the tempo a little at the end of phrases or sections and then returns to it or

changes it slightly at the beginning of the following phrases again, even if nothing is written down.

Thus, this is not to say that significant tempo changes are distinguishable in some places from

other places where there are indications. He frequently makes subtle tempo changes (whether

this is considered subtle or not is subjective to the individual) to make the beginning or end of a

phrase clearer or to change the character between sections.