Collaboration

The definitions of collaboration can vary in their shades of meaning. An etymological viewpoint could define it as "working with" from late Latin collabōrare, composed by con- and labōrare, "to work". Treccani reports as the first definition for collaboration "actively participate together with other individuals in a mainly intellectual work, or in the realisation of an enterprise, an initiative, a production", before defining the term in more specific domains18.

The definition of the term "collaboration" according to the Merriam-Webster English Dictionary is very similar. Their first definition of the word is "to work jointly with others or together, especially in an intellectual endeavor". It well represents the idea of the artistic intention of the collaboration, the composition of a piece involving two minds. Interestingly enough, the third definition given by this source is "to cooperate with an agency or instrumentality which with which one is not immediately connected": it describes the connection of the composers to this research project, which is inherently "mine", but it depends on the work I am doing with them. Both definitions are accurate, but the focus of this research will be the first one19.

The richness of meanings intrinsic to the term "collaboration" reflects the multiple possibilities in its forms and interpersonal dynamics that can occur. Moran and John-Steiner differentiate "social interaction" and "collaboration" based on the higher level of "blending of skills, temperaments, effort and sometimes personalities to realize a shared vision of something new and useful" involved in the second concept20.

Collaboration classification

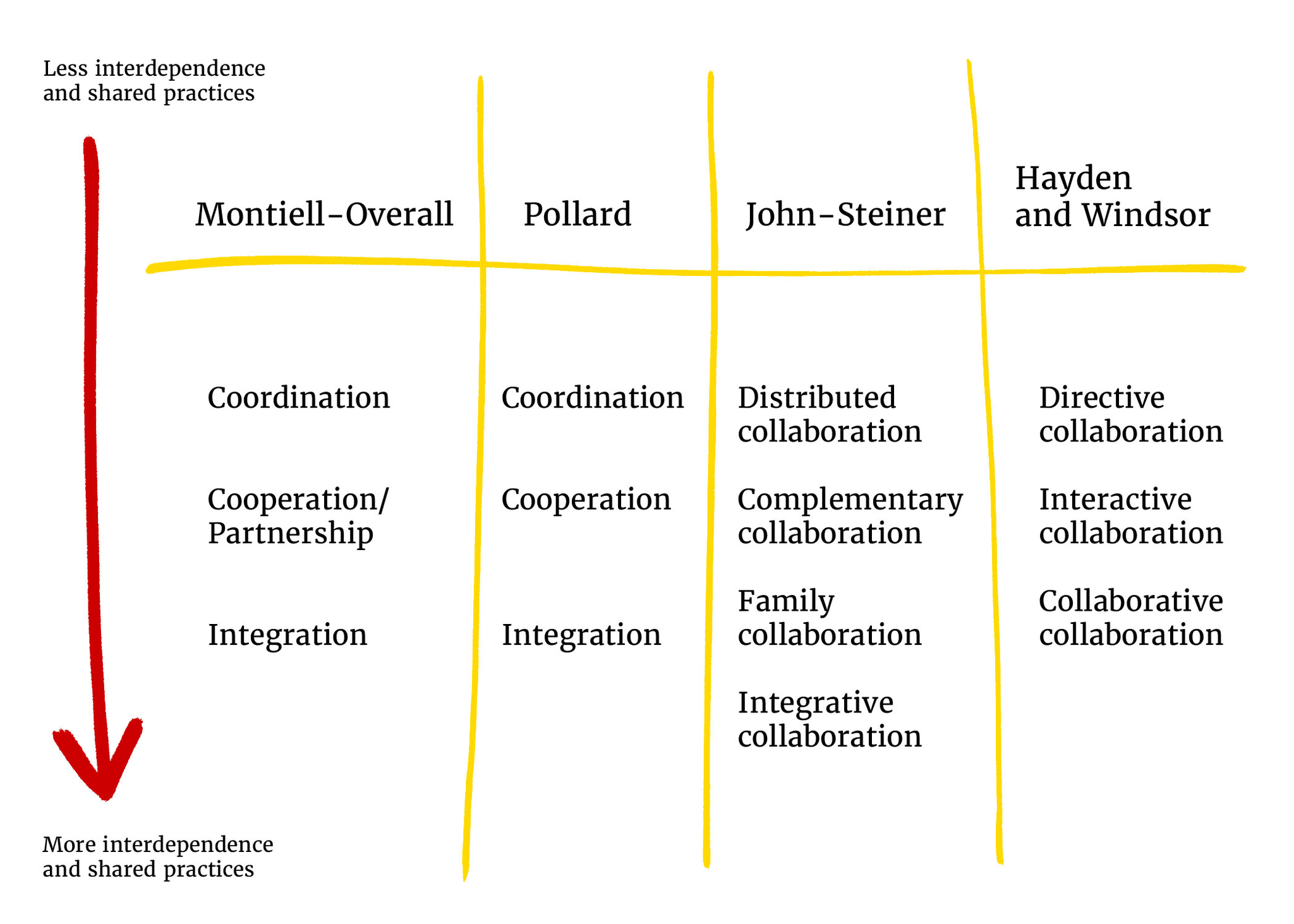

A clear overview of collaboration types is presented in a thesis by Paul Roe, "A Phenomenology of Collaboration in Contemporary Composition and Performance". This source has a quite similar approach to my research, and its theoretical framework was a starting point for my study. Nevertheless, I think that an exhaustive and in-depth taxonomy of collaboration is not needed in the present context, since it aims to fluidly explore different ways of collaboration.

I will limit it to a general schematic classification, to give the reader a wider contextualisation.

Based on the literature review, Roe collects different categorisations of possibilities for collaborative structures, patterns, and categories of collaboration (fig 1)21.

Attitudes about differences of opinion

Only once the project ended, I came across insightful literature about collaboration, which would have affected my choices if I had found it before the start of the process.

Interesting perspectives on relational dynamics in partnerships are proposed by Elizabeth Creamer, in a study where she analyses how divergent opinions can enhance the outcomes of collaboration26.

She profiles three groups of partnerships, based on their members' reactions to disagreement:

Like-minded, who believe that "differences of opinion are impossible or unlikely";

Triangulators, who recognise that divergent opinions are possible, but are convinced that they would not happen on important matters;

Multiplists, are partners that expect different opinions and consider them part of the process.

The author suggests that collaborative groups where this attitude prevails are those “where the link between negotiating differences and innovation is most evident”.

The first two groups try to avoid divergences and aim for continuous agreement on choices and ideas, their members are convergent thinkers. Conversely, the last group's members are "divergent thinkers who are comfortable with leaving some differences in perspective unresolved"27.

Creamer proposes that “deliberately constituting an interdisciplinary team, establishing clear authorship guidelines, and creating a culture where it is easy to talk about different viewpoints” are the keys to obtaining an environment where different opinions are valued and enriching.

In this study, I was aware of the probable emergence of different perspectives, and I tried to create an environment where they could be accepted and valorised.

In the conclusions of her study, Creamer lists five practical recommendations to enhance the multiplicity of ideas in collaboration28:

Create groups where members are equally experts in different but overlapping fields;

Nourish personal relational dynamics that support commitment and well-being;

Aim to build an environment where differences of opinion are enhanced by choosing an interdisciplinary team;

Make clear that every member of the group is responsible and invited to give feedback anytime;

Give space to informal conversations and exchanges.

Complementarity

The first and the last suggestions presented by Creamer are particularly meaningful, especially after having experienced the two collaborations that underlie this study: the need for balance in skills and knowledge and the necessity to include informal settings in collaborations are some of the conclusions I took from this project.

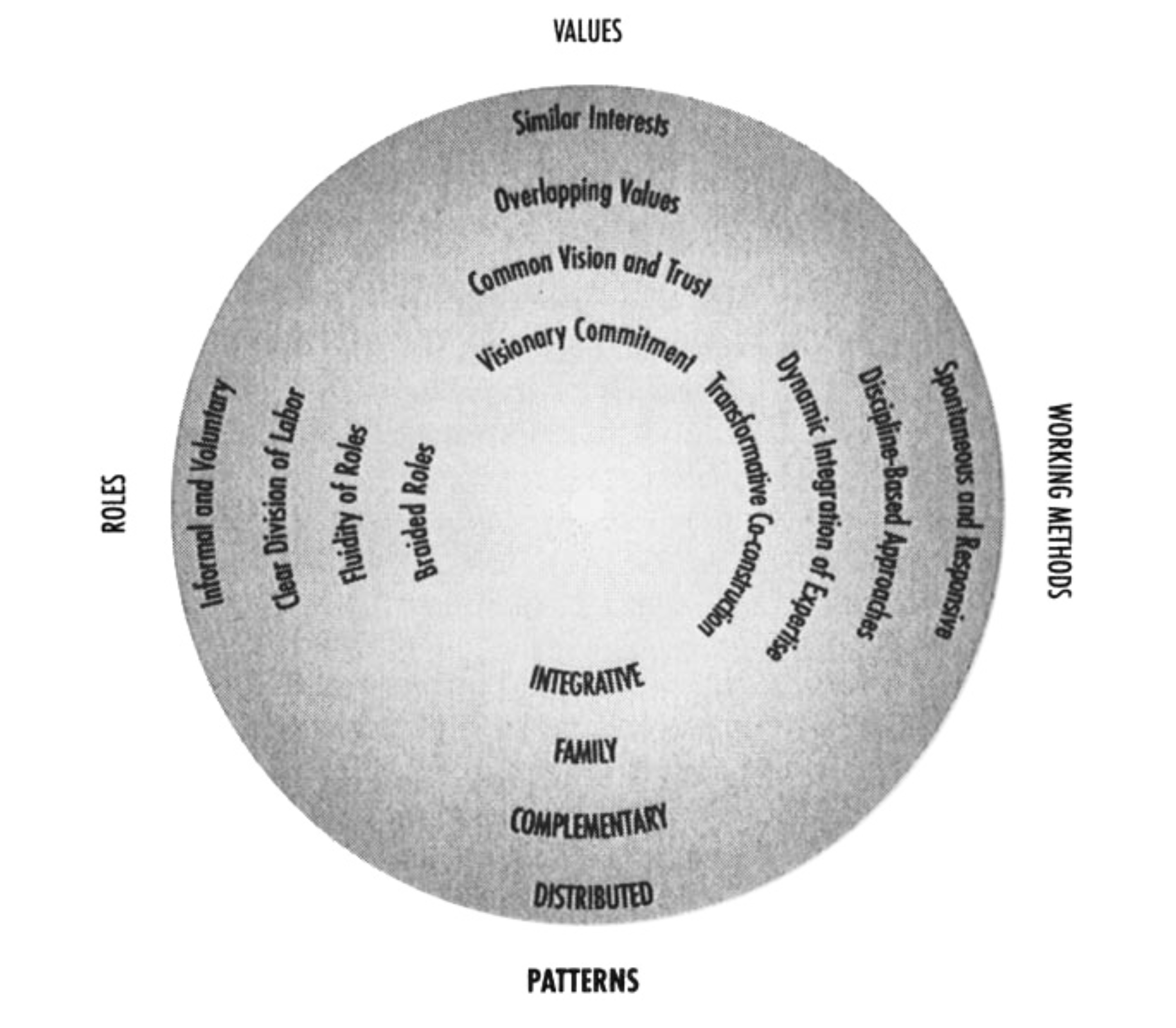

In the 7th chapter of Creative Collaboration29, John-Steiner supports Vygotsky's idea of proximal development, interestingly stressing the element of complementarity. This concept applies not only to fields of expertise but also to the process of discovering the other and learning from it, developing socially, emotionally, and personally. Complementary needs can lead to interdependence, and, subsequently, to a more likely creation of new meanings.

Autoethnography

The central point of autoethnographic practice is [...] «The praise of we, its comprehension through awareness of the self and of one's own experiences»30.

I would a posteriori define this study as "autoethnography". While involved in it, I did not realise how much it reflected myself, my path, and my personal growth. I was aiming for something more "scientific". Before diving into it, I want, however, to specify what autoethnography is to me now.

In the Prologo of his work, Gariglio highlights that "ethnography merges the recognition of others' expert knowledge and the reciprocal recognition in the diversity of approaches."31

I agree with him when he states, supported by other authors, that art and science share more than anything the use of imagination, creativity, and rigour, including reflection on experiences, actions, and their contexts, and therefore a complete separation of their approaches would be limited and useless, especially between art, literature, and social sciences. The present study integrates different disciplines: the chosen methodology comes from social sciences and psychology, and the bibliography comes from different focus areas.

Gariglio also defines autoethnography based on three main points32:

The researcher's roles of "tool", "object" and "measure" at once;

The central role of writing, with narration as a tool to better interpret experiences;

Essentiality of memory work by the researcher: remembering what happened and interpreting it, confronting it with the current ideas and opinions of the researcher and other individuals is a prerogative of autoethnography.

My project fits this definition, and even its title, chosen way before reading this source, shows how writing has an essential role in it: Collabographies.

My collaborations

Categorisation and classification

John-Steiner34 gives a comprehensive overview of different kinds of possible collaborative practices based on the variation of parameters such as the age or experience of one of the collaborators (Example: Copland and Bernstein from 193735), the number of participants, aims of the collaboration, individual engagement into the process and the specific dynamic balances originating from any collaborative practice.

The reciprocal regard toward the collaborator underlies all the case studies I found in the literature. It might seem obvious, but without respect and interest for others' ideas and thoughts, collaboration is not possible: the essential element of openness to the other would be missing. It could be interesting, as much as painful for the participants, to study collaborations between individuals who despise each other, but it is not the aim of the present study.

I kept this in mind when choosing my collaborators: I wanted to find composers who also were people I felt comfortable with, individuals I could agree and disagree with without damaging the reciprocal consideration throughout the process.

From the three meetings I had, I chose – mainly for a matter of time – to work with only two composers: Gaspar Polo Baader and Jasper de Bock.

The two collaborations I report in this research developed over a relatively short period: 10 months, compared to the decades of partnership presented as examples in many sources. The short time spent together was not enough for deep trust building and ease in risk-taking as collaborators, although the overall atmosphere was favorable to learning and experimenting. As newborn collaborations, my partnerships exceeded expectations but left room for considerable improvement. Instead of aiming for quick and superficial artistic outcomes, I preferred focusing on the comprehension of collaboration development to learn how to direct future projects.

Before diving deeper into the partnerships, I will present the adopted methodology to document and analyse the collaborations.