I moved to The Netherlands in 2019 with a nearly completed Bachelor’s degree in Composition. During my education at the Superior School of Music of Lisbon (ESML), I had already been feeling that my artistic creation was drifting towards the digital realm, as opposed to pure instrumental writing. I recently had a conversation with my dear friend and peer Zeynep Oktar about scores as an established medium for giving musical indications and we realised that my problem was two-fold: I have a constant score related tip of the tongue syndrome and a, for lack of a better term, classically trained musicians related social anxiety.

When I arrived at the Royal Conservatoire, I started working on a piece for Alto Flute and 8-Channel electronics in a cube shape (I was listening to a lot of Stockhausen at the time…). It was very fitting to work on this piece since my first composition teacher was Anne La Berge, a composer, (Kingma system) flautist and improviser. A pitch and rhythm system was devised to create all the musical material the flute would play but this piece was never completed as a result of a growing demotivation to actually make use of that system. Ultimately, I was getting no joy in writing the score of this piece, even though I somewhat enjoyed the material I was working with. The feeling that a score couldn’t reflect my sound imaginations started looming over me and it, later on, evolved into frustration. Why is it so hard to materialise the constant noise present in my head? It wasn’t the first time I was experiencing such a feeling, it had become a pattern every time I wanted to write a (score-based) piece. I would have an idea, build some kind of pitch and rhythm system, become unhappy with the process but I would still go on with it, even if it lead to a feeling of discontent with the result.

One example is the treatment of pitch in the Western European canon: it is divided in 12 rigorously defined and tuned tones. Everything in between, at least until microtonal practices became more common after the 50s, was not deemed feasible. And even within the realm of microtonality, composers like Ben Johnston still applied heavily formal structures, off-shooting from Webernian serialism, on top of this device, in my view a distortion of what microtonality could represent: a small step towards liberation from the “lattice”.5

The second point made in the previous quote is of special relevance to me. It alludes to the idea that the “lattice” is, in the end, a mere construct and a sort of illusion created by European composers to very meticulously write their ideas. Could it be just an ego-driven solution with the purpose of allowing their work to survive the test of time and acquiring total control over the musical outcome? The drawback is that the composer must “flatten” their sound ideas. Wishart describes this as reification, or the act of taking an abstract concept, like an emotion, and turning it into a quantifiable and easily definable object. A composer must describe their sound thought within a finite parametric system. This in turn reshapes musical priorities:

“Very soon we are beginning to deny the existence of any sub-label reality at all, and such things that we have called 'the emotions', or the highly articulate gestural response in improvised music which we may vaguely refer to as 'spontaneity', become as mysterious as Platonic ideals.” 6

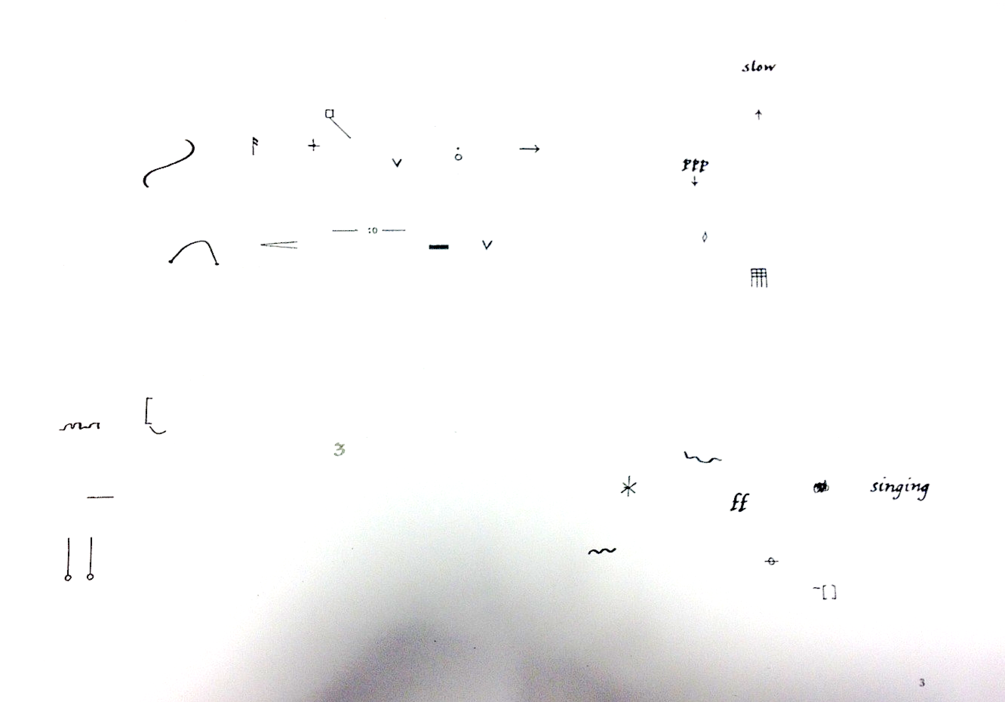

Now, I have a greater awareness that there exist many ways of engaging with a score as a concept but at the time, when studying in Lisbon and generally throughout my whole music education, an over-reliance on traditionally notated music was always present. But this was the construct (or “lattice”) that the faculty, institution, and subsequently myself, were working on. There is an inherent supposition of a “right” way of engaging with notation and scoring that has to do with putting intangible thoughts on a grid. Artistic creation becomes about finding a new way of cleverly permutating artificially constructed sound parameters. Music exists only on a pitch and duration paradigm and music performance turns into a contest of which player can play a passaggio more eloquently or getting all the musical parameters described on a traditional score right. To me, this is uninteresting. As an artist, I first and foremost want the individual identities of each performer to shine through. I see my work as a universe with certain constraints, built but not imposed by me, in which each player still has liberty to interpret the material given to them and, in a group context, performers are able to dynamically create relationships amongst one another, thus creating bonds of kinship and a space of shared values.

With this in mind, computer-assisted music brought the promise of liberation. I saw it as a medium where my sound fetishes could be fully realised. I didn’t have to worry about idiomatic instrumental writing, scoring or setting up rehearsal times with musicians. In the end, speakers are just there, ready to be used at the flick of a switch. When working on my acousmatic piece How to make a dadaist poem (which interestingly enough began as a piece for Cor Anglais and electronics) I felt an unrelenting pleasure in being able to generate and edit sounds on the fly, tweaking parameters such as loudness or reverb size to maximum precision, imagining how I would create an immersive environment on an 8-channel speaker system and, most important perhaps, having immediate feedback on how it sounded when playing it back through my speakers, even if at 2 a.m on a Tuesday. After starting to be more acquainted with Max/MSP and, more generally, the field of creative coding I could access another level of creative control, one that included being able to build sound textures from the very sample. And if computers complain they tell you exactly what’s the mistake, even if sometimes coated in a message that could be equated to prophecies from the oracle of Delphi. This leads me to writing about my first creation as a student at the Royal Conservatoire.

Coming back to my own experiences, all of these pre-compositional and compositional conundrums additionally caused insecurities when my own pieces needed to be rehearsed and performed. The act of having to gather people in a room, at a certain date, who would, out of the pure kindness of their hearts, use their own free time to play my “discontentment” piece was very confrontational. In a way, I owed these people more than a half-put-together score. At the same time, I wasn’t emotionally mature enough to coherently and structurally express my ideas in words, sound-wise or conceptually. It’s a feedback loop. The discontent felt towards the score became anxiety when having to ask people to play said score, which became an unhappiness felt towards the sound ideas tentatively expressed in the score, which became a discontent towards my compositional skills… and so on. Like my friend Zeynep said in a conversation we had:

“(...) maybe you don't know what you want, but you just want to try something. (...) you have a thought. You try to translate it into this really narrow thing, which is like this traditional writing method. And sometimes you just cannot find a way to put things. Like sometimes there's a feeling, but you cannot put it into words. I feel like music in your mind sometimes is like that (...) But maybe you can talk about it [as opposed to writing it].”

In On sonic art, composer Trevor Wishart speaks about “lattice-oriented” notation. According to him, the act of music composition, namely in the Western European context, developed so as to only exist on a very definable set of axis which do not allow for continuous steps to be made. He writes:

“The result is that music, at least as seen in the score, appears to take place on a two-dimensional lattice.3 Two things should be said about this lattice formulation. First of all it is our conception of what constitutes a valid musical object which forces 'musical sounds' onto this lattice; secondly, despite our intentions, the lattice only remains an approximate representation of what takes place in actual sound experience (except in the extremely controlled conditions of a synthesis studio).” 4