The Interview and its stages

This section consists of a report of the interview with Clara Scarafia I conducted in June 2023’: I will explain why her story will be the social element of my form of performance. I will go over the format of this interview, which consists of three stages:

- Monologue, where the interviewee talks about the social element freely, without interruption or time limit

- Researcher’s questions, where the interviewer asks his own questions concerning the social element

- Artisitic translation: where we outline the forms and feelings of the recurring emotions enucleated from the previous two parts of the interview, which will then serve to associate with the musical part.

I will not explicitly discuss the emotional content of this dialogue because, as also stated in previous sections of this research, I do not have professional psychological expertise, and the kind of show I intend to create does not purport to take on a therapeutic function. Therefore, although the content of the interview is interesting and full of very strong emotional suggestions, I will never address Clara's feelings with an analytical process, as her words are sufficient and exhaustive to understand her thinking. Any emotional reference that will be reported will be my perception, my interpretation of this reality, hence it will not be an objective truth. Furthermore, the entire interview, can be viewed along with subtitles and transcribed texts in the section called Appendix: Interview with Clara Scarafia. What follows, then, will serve as a demonstration of how I chose to organize my work, why I did it, and how I plan to incorporate the information I've gathered into my performance.

I have known Clara for ten years, since high school; I consider her one of the most important people in my life. We have spent crucial years together in our growth as teenagers and our first move away from home, living together for three years in our "new city," Turin. Such a long history of course is marked by contrasting events, moments of great joy, and moments that overwhelm you, that change your life and your perception forever. One of these moments was the Clara’s father’s death from suicide on March 22, 2022, a day that is now fixed in my memory permanently. I vividly remember my mother's call in the morning, where she reported to me that the lifeless body of Clara's father had been found in a hotel room. She had also told me that Clara did not know yet, that her mother would wait (our mothers work together) because it was the first day (if not the first it was still one of the first days) of Clara's new job, and as soon as she told her I would be available to go to her, so as not to leave her alone. One of the longest days I can remember. What should I have said? Would I have endured seeing her in such pain? What if I had said something insensitive? A series of constant questions accompanied me from morning and tore through until 7 p.m., the time I picked her up from her workplace. From then on I only listened to her words, her reflections, her courage. That evening, together with Clara's other very close friends, we shared her story, and it was something that I would not just call hurtful, but humanly wonderful: on that day I understood the meaning of the word community, its importance, and its beauty. I have always thought back to that story, also because we have talked about it several times, and as I was envisioning this research I thought that the social element I wanted to address in my performance should be Clara's story because it is the example of how an individual story, even if it is painful, can donate something different and important in the lives of others. Thus about a year after that fateful evening, I asked Clara if she would like to talk about her story again, because I wanted to do a show about her, particularly about that specific story. And that's what we did.

The interview took place over two days, the 2nd and the 5th of June 2023, at Clara Scarafia's home in Castiglion Fibocchi (Arezzo, Italy). The first two parts of the interview and the last one were conducted on these two days, respectively.

Since I had experienced Clara's story very closely, I feared that my view as a friend would erode my ability to gather new nuances. I was worried that my vision might somehow override Clara's reality, that I might have been led to prejudice or hasty and false conclusions by the thoughts I had constructed about her confidence. The risk, when you are very familiar with a person, is that you think you know every side of his or her personality because that person has told us so much about their life that you think they are intelligible to our vision. So, wanting to portray Clara's story with the respect it deserves, I needed to start with a new narration that was free from my preconceptions and on which I could make a new reflection. So in this first part of the interview, which I dubbed "Monologue," I decided that I would not speak, I would not ask some questions, I would not pose my point of view: I needed Clara to be able to conduct a free narrative, without limits, where she could pass inside every tunnel of her mind without being afraid of being off-topic or verbose. The only information Clara had was that I would turn the camera on when she was ready, and that she could tell, without any time limit or censorship, her story concerning her father's death.

Clara begins her talk by taking inspiration from a concept that struck her at a semiotics conference, they said this: "Semioticians, psychologists, and sociologists now agree on the idea that human beings live immersed in a primarily narrative reality; for example, in the field of psychology it is noted that difficulties in narrativizing one's life experience can generate a state of severe depression, or even a decision to commit suicide - the result of a condition in which, precisely, 'here is nothing left that can be told.' " 1She then finds in her father's behavior this association between the lack of narrativization and the possible depressive disorder that can result in suicide. The monologue continues using the artifice of the example: in fact, to exemplify this concept of narrativization she cites this time the story of ZeroCalcare's (Italian cartoonist) two graphic novels "Macerie prime" and "Macerie prime sei mesi dopo." In this story, the protagonist never actively participates in the dialogue and does not narrate herself – as if she does not have to power to do so. Clara explains how it later turns out that this character attempted suicide, after a long period that she had disappeared from the lives of the other protagonists. She concludes the monologue, still referencing ZeroCalcare's story, by stating how important it is to be present in the lives of people who are facing hardship, in whatever way. However, reflecting on the fact that his father received a lot of help from his peers, she states that, unfortunately, the support is not the only solution.

This is the more "traditional" stage of the interview, where questions of various kinds are asked in order to reconstruct the story from different points of view. The goal of this part, like the previous one, is to enucleate the most recurring states of mind within this story, thus looking for the element that can be made universally relevant: I may not understand what it means to lose a parent, yet I can understand the pain and so I can empathize with a person who has a different story than mine. To begin this interview therefore I wanted to start with the concept of universality. In particular, I had prepared questions about the relationship with friends and the freedom of being able to talk about the suicide. I was also very interested in Clara's perceptions of the other's people judgment might feel and, more generally, to know if she imagined what their emotional perceptions were regarding this story. I tried not to follow an orderly schedule because I always wanted to let Clara have total freedom to narrate but, compared to before, I allowed myself to ask her for insights, to get as clear a picture as possible.

In this interview, starting with her relationship with the outside world, we reconstructed the day of her father's death, both emotionally and narratively, going into who she had spoken to, how she felt in doing so, and how, fortunately, she immediately felt protected by her loved ones. The first feelings she felt were more physical in nature than emotional, as she says, "I was really feeling a physical sensation of almost a very strong tingle."2. Next, we also reviewed the days after the incident, highlighting a desire to seek many distractions, to avoid reflecting on her father's dead, and to try to feel good: she describes this as a survival mode, how it was essential to allow herself time not to think, seeking fun and excess, to afford moments of true happiness. However, she also talks about some moments of the day, such as the night, where thinking did not let her rest: there are thus characterized by a strong feeling of oppression, where distraction is not possible. We then again returned to talk about the relationship with the outside world, how free she felt to be able to express her reflections but at the same time how she always tried not to make those who were listening to her feel uncomfortable, because she recognized the emotional magnitude of the suicide topic. Still concerning the relationship with the outside world, we also discussed what is generally expected of a person who suffers such a bereavement: Clara's reaction therefore is primarily a physical one, which as she explains, is related to the sense of injustice3 derived from the impotence of finding herself in a position she did not choose and from which she received consequences that she had to resolve on her own.

Reflecting on my emotional perception of these two parts of the interview, I chose the emotional states of mind that would be addressed in the last step of the interview. The first emotion is anger, which, although it was never formally addressed in the interview, I believe can also gather in its shades of meaning the "sense of injustice," "the feeling of oppression," and the feelings of a physical nature described by Clara. The second feeling/state of mind I chose to explore was the desire for escape/survival spirit/dissociation (which from now on we will just call dissociation). Finally, Clara had the opportunity to deal with other feelings in the last part of the interview, choosing the state of mind of loneliness.

This last part of the interview is devoted to the study of the emotions enucleated in the previous two parts. The goal is to try to describe these moods through all the related sensations, their causes, and consequences always trying to include them within the narrative of the story. Thus at first Clara will give a personal meaning to each feeling and after that she will try to express them through artistic concepts, having the possibility of drawing shapes, pictures, or quoting songs, books, movies, and any form of art that can be representative of such feeling. This part will serve the purpose of gathering the emotional material that will enable the musical association between the mentioned feelings and the piano works. These, in turn, will constitute the narrative setting of the performance.

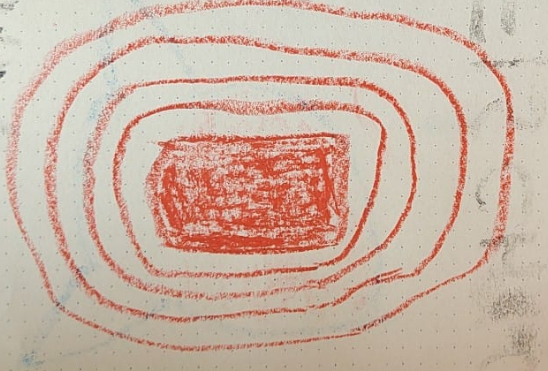

Clara begins to explain her relationship with anger in general, describing the role it played during her adolescence and how it also manifested itself in her relationship with her father. She also explains how in her case anger has a generally positive approach, "because it pushes me to change, to fix something"4. Clara then expresses the physical sensation she associates with anger, as an energy that forces on her shoulders and needs to be discharged. After her father's death, however, she speaks of a different anger, one that spills over into the resolution of bureaucratic problems related to the affair, an anger that then never actually takes shape. An emotion that stems from an uncontrollable sinking feeling, the consequence of which can be very dangerous and therefore needs to be directed into controlled actions that can mitigate this destructive force. Clara reports that after her father's death, she had only one episode, coinciding with her father's birthday anniversary, where anger took over, and thus she was unable to channel it. Trying instead to represent anger artistically, we see that it is represented by an expanding red rectangle, growing inside our bodies until it bursts. The sound Clara reports is that of a teapot whistle, "it's like some hot air, a lot of hot air condensed in one spot that then rips you apart"5. Lastly, he mentions the characters of Stitch in the animated cartoon "Lilo and Stitch" and Princess Flame in the animated series "Adventure Time", showing how the anger of these characters arises from situations of severe discomfort that nevertheless, thanks to their intelligence, can be conveyed to become better people.

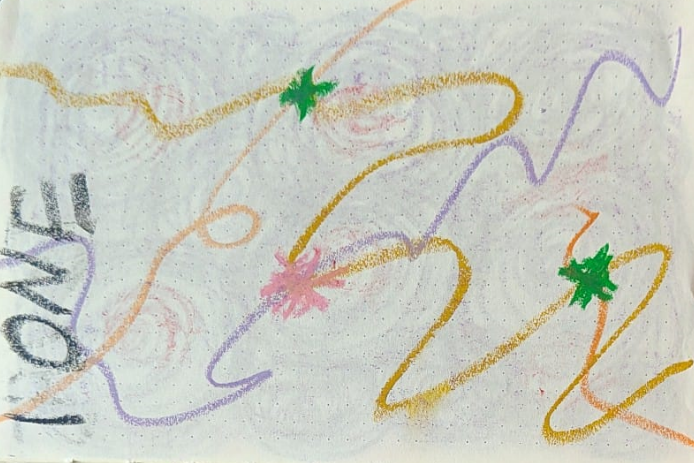

Clara describes distraction (which we also find in the interview under the name escapism) as that state of mind that allows you to access different forms of reality, through, for example, literature, music, and film. Dissociation, on the other hand, is different, where one's cognition becomes disconnected from reality, "I've been like two days that it's like I'm not there"6. She physically describes distraction as "stagnant, calm, serene water of the pond that you look at it, now and then there's some ripple however it stays there, it's calm"7 while dissociation is something indescribable because it results in apathy, then absence. However, both of these two states of mind have in common the suspension of reality, which can be positive in the case of distraction and negative in the case of dissociation. In Clara’s drawing this suspention is represented as a purple curtain, something strongly stable and secure, where, in the case of distraction, we find in it new feelings (colored by the red asterisks) that enrich and improve us; for dissociation there are no new feelings, the curtain completely anesthetizes reality, resulting in apathy. Under the purple curtain instead is reality (which she draws on the adjacent page), defined as "a whole series of variables of issues, of situations, of feelings that are all completely different and they all come from different parts; sometimes they don't end because anyway, it's sudden stuff that then goes away"8. In the rest of the interview, Clara takes a lot of films as examples, partly to explain the phenomenon of dissociation in itself (Like Donnie Darko) but at the same time she goes over through her 'film diary' all the filmography watched after her father's death. Clara explains how films are both a way to escape from reality but also a way to reflect on her reality, touching on related feelings or taking films that are part of her past or even films that talk about issues close to her story. The interview closes with a scene from Wes Anderson's film "The Tenenbaum" where one of the main characters attempts suicide.

Throughout the interview, Clara articulates the nuanced aspects of loneliness, attributing it to both internal and societal factors and she perceives loneliness as a pervasive emotion that permeates various aspects of life, contrasting it with more tangible feelings like grief or societal rejection. She suggests that loneliness, while universal, manifests uniquely for each individual, influenced by personal experiences and societal dynamics. By drawing numerous blue swirls that pile up against each other, she depicts loneliness as a force that pulls you down and puts you at risk of becoming blind to reality, “I have the impression that when the whirlpool pulls you in, it's very difficult to remember that there is something else outside”9. Clara discusses her reluctance to fully empathize with her father's loneliness, fearing the potential impact on her mental well-being so she consciously distances herself from delving too deeply into her father's emotional state, recognizing the potential for personal hurt. Clara's introspection reveals the delicate balance between empathy and self-preservation in navigating complex emotions. She reflects on her ongoing struggle with loneliness and the efforts required to mitigate its effects acknowledging the cyclical nature of loneliness and describing moments of isolation interspersed with periods of connection and support. Clara concludes the interview by drawing what it feels like to come out of the vortex, representing all that is not loneliness: wavy lines that support you, that lead you to recognize those incentives that you could not see before, while inside the vortex. The lines are not straight because there is an awareness that it is always possible to fall back into the vortex from loneliness but there is a hope that coming out of it you will still find those stimuli that make life worth living.

Musical Combination

In this chapter, I will explain the process of selecting musical pieces that will serve as the musical and emotional backbone of my performance, building on the sentiments discussed in the previous chapter. The approach to this selection is varied, considering factors such as compositional style, nuanced agogic indications, evocative timbres, and insights into the composer's life. At the heart of this decision-making process is the concept of emotional resonance: the identification of pieces that can authentically evoke the inner world of Clara in the audience. The music should be intricately woven into the narrative, shaping its dramatic cadence, rather than merely providing a backdrop. I will then explore the synthesis of Clara's dominant emotions with the selected pieces, using parts of the interview and musical excerpts to illustrate this alignment.

FROM ANGER TO GRAZYNA BACEWICZ

The piece I chose to represent the state of mind of anger is the Piano Sonata No. 2 by Grazyna Bacewicz, an early twentieth-century Polish composer. I discovered this composer thanks to Krystian Zimerman's wonderful album "Grazyna Bacewicz" which features the above sonata together with the two quintets for piano and strings. I remember that listening to this sonata impacted me mainly on a physical level: a piece of rough music, with violent parts that are even more strident when contrasted with the more lyrical and intimate parts. I searched the composer’s biography for elements which could support this violence, but I could not find any specific connection. However, there is one detail that I think is very interesting in terms of the idea of the composer's compositional activity: “For me the work of composing is like sculpting a stone, not like transmitting the sounds of imagination or inspiration”10 . Among the different interpretations we can find in this statement is the possibility of associating music with a lump of nothingness that has to be shaped into precise forms: I think this perfectly reflects the attention to structure and proportion in Bacewicz's composition. Moreover, this physicality, both sound-wise and structurally, also reflects Clara's description, where it is the physical element that represents anger, as we find in her words: “hot air condensed in one spot that then rips you apart”11 or “I imagine it (anger) a dense stuff, like lava.” 12. Once we have found the general connection between Clara's emotional material and the piano work, we can go on to analyze specifically what musical parts represent some of the details of Clara's interview.

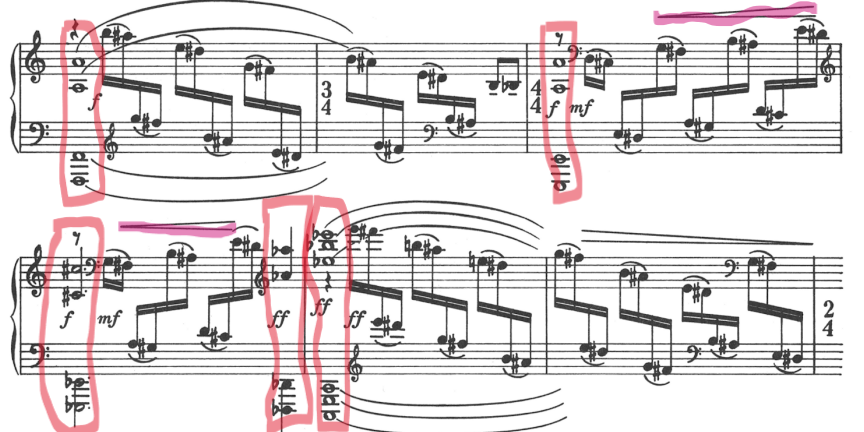

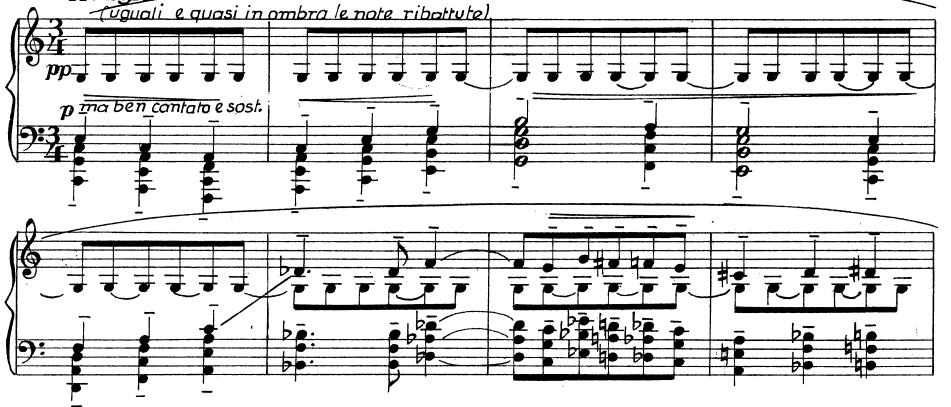

One of the elements that I wanted to try to reproduce musically is Clara’s representation of anger, which she explains as: “a red rectangle [...] the moment it is triggered it expands, it expands a little bit more.”13 I found a correspondence to this description and image in a substantial section of Bacewicz's development of the first movement (Maestoso - Agitato):

We observe how this whole part is characterized by a long crescendo realized through the use of a succession of sixteenths notes tied in couples and distributed between the two hands. The rectangle, thus the block of matter, we can be compared to the first chord under the fermata, a augmented seventh with major seventh chord which, although it is under a fermata representing the end of the previous section and considering its strong instability, needs its resolution in the next episode, that is, the one of the long crescendo. We imagine the chord below the fermata as the shape of the red rectangle and the following sixteenths note, with the crescendo and change of tempo, as the red widening lines of the same rectangle (as in Clara's drawing). After eight bars of crescendo of the sixteenths note we land on a new chordal block (a new, larger, and louder rectangle), and again the sixteenths note (or widening lines) lead us in progression to a new chord rectangle until we arrive at the last one that represents the climax of the section and it could therefore express the feeling of explosion (or sinking) that Clara describes in the interview.

Another element I found in this sonata is the description of Clara's first night after her father's death: “I didn't sleep practically the whole night because the moment I lay down and tried to think about even trying to sleep, I felt a very strong oppression, that is, I felt like I was being crushed [...] for the first time in my life. It's a feeling that I had never felt even at times when it would make more sense to feel it, which is a very great fear of dying, at that moment there I really felt that if I lay still I would die too” 14. In the second moment (Largo) we can find several elements of this description, and more generally we can say that we find this shadowy and oppressive atmosphere throughout the movement.

The entire first section is characterized by a chordal accompaniment divided between the two hands, which seems to lull us into a conciliatory sleep; the nocturnal atmosphere is underscored by a static, repetitive melody that, after the emotional turmoil of the first movement, seems to want to reassure us.

However, this is only an introduction with the purpose of habituation to this twilight setting because the apparent calm of the first part ripples after sixteen bars. This emotional change occurs first from a harmonic point of view, moving from simple major and minor seventh chords to more dissonant chords of a polytonal nature, and then from a melodic point of view, moving from perfectly tonal, folk-like melody to a distorted atonal melody.

It is precisely in this section that I find the sense of oppression described by Clara, an atmosphere that slowly becomes heavier and heavier causing a strong state of anxiety. The feeling is just as if this oppression is trying to explode, trying several times and succeeding but, moments later, it is as if the night swallows up all the sounds again and brings us back to that electric state, where the perception of danger is constant and increasing. We see two slow anxiogenic crescendos that end in a terrible climax (bars 29 to 42 and 50 to 69), but both are then brought back to a dimension of silence, of forced calm. We see how especially in the second crescendo this dynamic abyss is evident, going from a FFF to a pp in the time of a dotted quarter note.

The fear of death voiced by Clara in my opinion is perfectly expressed with the ending of this slow episod, moving from the second and final climax to the initial distorted melody, and finally, just as if we were walking the path again in the contrary, we conclude with the initial introduction, this time, though with the indication "poco più mosso." The change of tempo and the premature interruption of the exposition of the introduction's theme leave an uneasy feeling, as if the thoughts leave no space for our minds to rest and, with barred eyes, we stare at the emptiness in the dark ceiling.

The last element from Clara’s account of anger that could be expressed through this sonata, is the description of how, during the grief, Clara avoided the real explosion of the anger: “I have to figure out how to make things work after he is gone and he left us with certain tasks, issues-that anger there I focused a lot on these practical things, the issue of the funeral, the issue of the lawyers, of the waiver of inheritance,I had to very much project myself on that thing there. And I vented it in that way at the end, I mean I don't know, I was so angry that the various bureaucratic stuff that usually would have weighed so heavily on me to do, I almost didn't feel it because I knew that the moment I would finish doing those things there I would then have to go back to thinking about how I actually was and I didn't feel like doing that. And then, however, by the time I had time to think about it, it had kind of run out of this anger thing” 15. This strong emotional detachment can be represented by the short Toccata of the third movement, which compared with the previous two movements seems to change the atmosphere considerably, and also change the compositional style profoundly.

A distinctly neoclassical type of writing, where the themes and ideas covered are used with very limited variety. It appears as an emotional disconnect from the first two movements, destructive and wearisome respectively: suddenly the narrative dries up and leaves space only for sensationalist effects of a more virtuosic nature. The only contrast within this movement is the "poco sostenuto" where Bacewicz seems to recover the oppressive and violent atmosphere of the earlier settings, as a sudden and yet ephemeral moment of lucidity, exhausted within 34 bars.

This repetitiveness and lack of emotional impetus seem, in my opinion, to represent the bureaucratic and technical actions that Clara had to deal with in the mourning period, as serving to put on standby what she would then have to deal with, thus anesthetizing the anger that could have set her off. We thus also begin to introduce the next state of mind: dissociation.

FROM DISSOCIATION TO MARIO CASTELNUOVO TEDESCO

I decided to pair the dissociation part with the Piano Sonata op. 51 in C major by Mario Castelnuovo Tedesco, an Italian composer of the early twentieth century. In the last two years I have been paying special attention to the works of Italian composers of this century because of the eccentricity in stylistic writing, the scarce performance within the concert circuit, and also to reconnect to my native country. In particular, I appreciated the compositional work of Gian Francesco Malipiero and Mario Castelnuovo Tedesco, as a plurality of contrasting psychological characters emerges distinctly in their works through a discrete alternation between languid and melancholy moments and more wrathful and overwhelming moments, musically representing the climate of insecurity of the 20th century. Considering this stylistic peculiarity, I decided to go through much of their compositional output, thinking that I would find a good option to translate the complexity of the theme of dissociation described by Clara. After a first listen, I was immediately struck by Castelnuovo Tedesco's Sonata Op. 51, because of its proportions, sound world, and instability.

The sonata is articulated into three movements that appear as three independent blocks, having similar dimensions (each movement lasts about 7 to 8 minutes) and no musical material in common. This proportional element weakens the narrative structure since the deprivation of a short movement does not allow the natural release of the structural tension of the longer movements, making it difficult to find a climax within the whole sonata. Let us take as an example one of the most monumental sonatas in the classical tradition, Beethoven's "HammerKlavier" Sonata op. 106, four movements with a total duration of forty minutes: Beethoven fits in as the second movement a Scherzo of about three minutes that serves precisely to lighten the structure before the gigantic third movement. We should therefore identify in this proportional/structural instability of Castelnuovo Tedesco's sonata an element of serious criticality, and although this may be the case, I believe that the effect of alienation that it could induce in the audience can very effectively represent Clara's brief and accidental description of dissociation: “I've been like two days that it's like I'm not there”16.

Analyzing the first movement of the sonata (Rude e Violento), I found interesting the numerous agogic suggestions that Castelnuovo Tedesco uses, as opposed to the melodic and rhythmic material that appears sparse and very repetitive.

I will now list all the agogic indications from the start of the movement, along with their respective translations: Rude e violento (Rough and violent), scuro e misterioso (dark and mysterious), deciso e squillante (decisive and bright), appassionato, un poco ansioso (a bit anxious), imperioso e ben ritmato (imperious and well-rhythmed), aspro (sour), leggero e volante (light and flying), implorante (begging), secco e tagliente (dry and sharp), stridente (strident), fieramente (proudly) and pesante (heavy). This tangle of indications overlapping one another immediately brought me back to Clara's description and graphic representation when, speaking of dissociation as an anesthetizing element, she defined her concept of reality: “a whole series of variables, issues, situations, and feelings that are all completely different and they all come from different parts. Sometimes they don't end because anyway it's sudden stuff that then goes away. [...] when they go to touch they create stuff [...] that hurt you.”17 Even musically, therefore, the entire movement has a very overexcited character, which in the repetition of the few thematic ideas and the use of very bright colors, perfectly expresses the overwhelmingness described by Clara earlier.

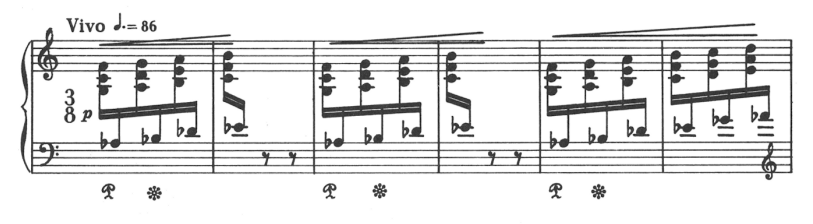

The second movement (Adagio) immediately departs from the electric character of the first movement, using writing closer to the late Romantic style but, at the same time, also new styles from non-European cultures, such as the presence of two blues. The first part of this second movement, characterized by a constant repeated note, seems to recreate the state described and experienced by Clara when she manages to abstract herself and thus escape from reality:” it's like the stagnant, calm, serene water of the pond [...] there's some ripple however it basically stays there.”18

The whole movement has this floating dimension, without shocks and with very tenuous colors: Castelnuovo Tedesco builds a rarefied sound setting with new agogic indications compared to the settings of the first movement, such as "con una sonorità fioca e velata" (with a dim, veiled sonority) or "come una danza velata"(as a faraway dance)

This Adagio represents for me the purple blanket drawn by Clara, the one that allows one to anesthetize reality when it is no longer manageable: “It's kind of something like this, that is, I am going to create indeed a situation where there is an underlying basis that is very stable and so I know that I am within that thing that causes me to break out, and that it is somewhere else than the rest that is to what is conscious what is pure presence and pure action in the things of life. But still within that stability there are feelings, because still the things that I go to do, to see, to read create an internal reaction in me. So it is as if there are little flashes precisely of emotions, of feelings, however, they are flashes that are contingent in that sphere there, whichis a sphere anyway that takes me outside of myself.”19

The third movement (Allegro furioso) partly takes up the character of the first movement, but with many ideas and thematic re-elaborations, thus showing itself very varied and winking. A bright and pyrotechnic sonorous range predominates, indulged by a pressing and fast rhythm: the agogic indications are lighter, in fact we find such phrases as "leggero e danzante" (light and dancing), "grazioso e scherzando"(gracious and joking), "festivo" (festive) or the more widely used "grottesco" (grotesque).

This atmosphere filled with life seemed to me to be perfect to represent Clara's need to seek fun as a form of venting and recreation, the need to not have to think and have this need to also be able to get lost: “I remember [...] spikes of intemperance like drinking, going out during the week even though I knew I had to work the next day. It was a big thing, which I wouldn't have done before because anyway I was always quite careful about how to handle things. I always allowed myself moments of venting and intemperance [...] as I found myself in situations where I kept drinking even though [...] because I didn't want to think, I didn't want to be present, I didn't want to be perceived at that moment and so the best way to not be perceived was not perceiving myself first.”20

FROM LONELINESS TO GABRIEL FAURÉ

For the last state of mind, loneliness, I have chosen a selection of preludes and nocturnes by the famous Gabriel Fauré, namely Preludes No. 1,3,7 op.103 and the last two nocturnes (No. 12 op.107 and No. 13 op.119). Loneliness is one of the most represented states of mind in piano literature, especially in the 19th century and even the first years of the 20th century, just think of how many composers have for example musicalized Goethe's "Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt" (Surrender to loneliness). Precisely because of this high prevalence, it was difficult to find which pieces were most compatible with the loneliness described by Clara. For this kind of combination, I was also inspired by the composers' biography, and their relationship between life and music writing, thus finding in Fauré's last style the most appropriate key. Fauré's last style or third style began around 1904 and lasted until the composer’s death in 1924, “is marked by compositions of a quite particular style, of a sombre gravity at times, of an austere resignation, more and more closely clipped, laid bare, gaunt almost”21 . Although in the latter period he became Director of the Paris Conservatoire, Fauré began to suffer from deafness and migraines, and, as is also evident from his correspondence with his wife, the frustration of not being on par with other composers of his generation. According to other musicologists, however “the origin of Fauré’s predicament was purely artistic: his personal aesthetic had changed, but his musical style and technique had not”22 .

For this musical-emotional combination I could not find musical and textual examples as I did for the previous states of mind (anger and dissociation), because both musically and from Clara's testimony, the elements I wished to associate did not correspond to precise details (elements of a verbal nature), but rather it was a general feeling given by the fusion of Clara's and Fauré's affective material. The selection of Preludes Op. 103 and Nocturnes Op. 107 and Op. 119 are a light within the most deafening darkness, which through very transparent and clear piano writing manages to paint an intimate setting that evades the reality of the world. And so, as in Clara's interview, what touched me strongly was not only her words but her gesture in the act of drawing the vortex. As I saw that circulatory gesture, that calm and repetitive movement, I felt myself sucked inside that vortex Clara was drawing, engulfed by that silent force with such power that it obscured any other thought or voice. Although I had thought before that moment that I had never experienced loneliness, in that vortex I felt Clara's loneliness and my loneliness, being able to see it even in the small experiences of my own life. To demonstrate the synergy I felt between these pieces and Clara's gesture, I propose the same test I tried on myself: I edited the video of the looped interview with only the part of the vortex drawing until I totaled about the same amount of minute time corresponding to the duration of Fauré's pieces. Since I have not yet been able to record these wonderful pieces I will recommend versions on Spotify or youtube in the order I have imagined to be heard along with the silent video of the vortex drawing. Since this is a test of about 20 minutes, I will also recommend just a nocturne to accompany the video of the gesture.

1) Gabriel Fauré "les nocturnes, les préludes, thème et variations - pièces brèves": Preludes, op.103 no,3 in g minor. Jean-Paul Sevilla (piano)

2) Gabriel Fauré "Nocturnes & Barcarolles" Nocturne No. 12 in E Minor, Op.107. Marc-André Hamelin (piano) Hyperion

3) Fauré "Nocturnes": Nocturne No. 13 in B minor, Op. 119. Eric Le Sage (piano)

4) Gabriel Fauré "Prélude - Impromptus - Thème et variations" : Prelude no.1. Paul Crossley (piano)

5) Kun Woo Paik plays Gabriel Fauré: Prelude in A, Op. 103, No. 7. Kun Woo Paik (piano)

If you want try the short test, try listening only the Nocturne op. 107.