When taking a closer look at Hindemith's Solo Sonata Op.25 No.1 and music at the time it was created, we discover it was really something special. At the end the 19th century, an era in which the art of writing for solo stringed instruments had been lost and harmony had taken over from melody, the first works for solo strings after Bach started emerging. Barely any works had been written, featuring the solo string instrument in repertoire of equal speaking power as the (chamber music) sonatas and concertos (for soloist and orchestra) that were so popular in the 18th and 19th century. The few works for solo strings that had been written during these centuries were mainly meant as etudes or as more virtuoso showpieces, like Nicolo Paganini's 24 Caprices or Henri Vieuxtemps' Cappricio 'Hommage à Paganini', and were all fairly short in length, never meant to express a full emotional journey as we see in the Bach suites as well as in the suites and sonatas for solo strings that start emerging at the start of the 20th century.

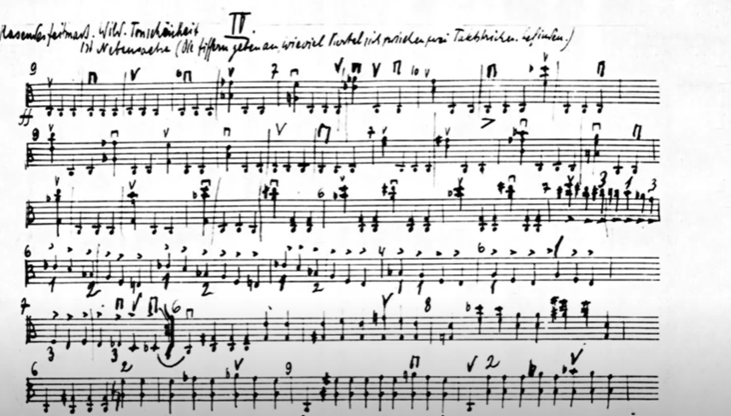

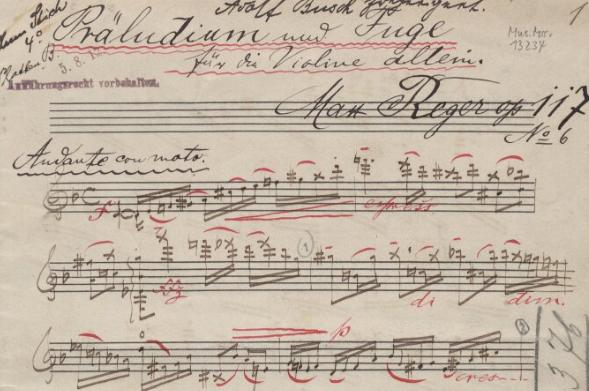

This change of direction in composition is believed to have started with Max Reger writing his first solo sonatas for violin in 1905.1 These solo sonatas were later followed by two cycles of 3 suites, one for viola and one for violoncello, written one year before Reger’s death in 1916. Another pioneer, although maybe less of a direct influence on Hindemith, was Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967), writing a sonata for solo cello, including scordatura, in 1915. By reviving this style of writing for solo instruments, which had become unusual during the late 18th and 19th century, a shift was created, that inspired many to follow in their footsteps. One of those being Hindemith, as he created his first work for violin solo, the violin sonata in G minor, in 1917, only one year after Reger’s death. Coincidentally, this was also the same year that music researcher Ernst Kurth (1886-1946) published his book about counterpoint, including information about how Bach built melody inside his polyphony. Taking all this into account, this emergence also showed melody taking over the importance from harmony which was an art that was long forgotten.

Hindemith’s solo violin sonata was only the start for him, because after he himself switched to playing the viola in 1919, he left an enormous legacy of viola repertoire. He started with his first viola solo sonata Op.11 No.5 as well as a Sonata for Viola and Piano Op.11 No.4, both written in his first ‘official’ year as a violist.

The year 1922 came with Hindemith’s discovery of the viola d’amore as well as his one year anniversary of playing in his Amar Quartet. Under the influence of all the different styles of music he came in contact with, due to his many interests and busy performing occupation, the Solo Sonata Op.25 No.1 was born in 1922.

This, although it being his second solo sonata for viola, was Hindemith’s most beloved and most performed of them all. Records show a list of performed repertoire and concerts going only until 1931, and he performed this sonata 58 times in the span of just 9 years.2 This strong connection is another element proving the unity of composer and performer that could be found in Hindemith and was rare for his contemporaries.

Hindemith was known to be an extremely talented virtuoso violist during his time but the story behind this sonata also shows that he was self-assured about his own playing and composing abilities. Hindemith wrote a letter to his publisher about him playing a new viola sonata the next day in Cologne, saying he had yet to write the opening (first) and the final (fifth) movements of the sonata, but that he would compose them in the train from Frankfurt to Cologne. This, showing that there was no emergency or reason for him to be obliged to finish or play this sonata the same evening as finishing it, demonstrates a rather planned approach combined with a willingness and confidence in his own skills.

Hindemith’s status as both an excellent performer and composer can also be derived from the following quote by a Swiss critic (about Hindemith’s performance of the Solo Viola Sonata Op.25 No.1): When the small, slight man appears before us with his big viola, enthusiastically and confidently, he plays something for us that signifies the new German instrumental music, whatever that may be. And we have no one at the moment who does it better – playing as well as composing – except perhaps for Hindemith himself if he continues like this. [...] Corresponding with contemporary taste - people have become so impatient - everything is arranged as briefly, tersely and clearly as possible. The ‘new’ is primarily the high pressure of an almost unbelievable virtuosity approaching that of a machine, as well as the disintegration of tonality. We have rapidly grown accustomed to this free harmonic language; for a long time now, it has not been felt to be so essential. But the virtuosity? One has the feeling that Hindemith, as a player and composer, simply does all this off the cuff.3 The comparison between Hindemith’s virtuosic skills and a machine is an interesting reference which fits this time of industrialisation of society very well.

It isn’t surprising that this solo sonata surpassed the first one for Hindemith’s personal preference as there was a note in Hindemith’s personal score of the piece saying “as a replacement for my first viola sonata”4, showing his unhappiness about the final result of that work. Hindemith continued to write more works for viola as well as two more solo viola sonatas, although none seemed able to exceed the second one as Hindemith’s personal favourite.

The combination of Hindemith’s fascination with early music, being strengthened even more through the discovery of the viola d’amore as well as the general resurgence of interest in the early music style and forms after the world war gives for an interesting work showing the immense world that can open up when history is combined with modern times.

Being aware of how this composition came to be, with its first and final movements written last, presents me with an interesting perception of seeing and playing those movements as a prologue and epilogue around the actual core, second, third and fourth movements, of the piece. This combined with how Hindemith performing this piece was perceived, adds to my knowledge of what he might have tried to express. Having a small look inside the composers mind opens up an enormous world of ideas of interpretation.

[1] Danuser, Hermann. Über Hindemith: Aufsätze Zu Werk, Ästhetik Und Interpretation. Mainz, Schott Musik International, 1996. 113.

[2] Danuser, Hermann. Über Hindemith: Aufsätze Zu Werk, Ästhetik Und Interpretation. Mainz, Schott Musik International, 1996. 114.

[3] “Further Concertising Activity: Paul Hindemith.” Hindemith Stiftung, www.hindemith.info/en/life-work/biography/1918-1927/work/further-concertising-activity.

[4] Danuser, Hermann. Über Hindemith: Aufsätze Zu Werk, Ästhetik Und Interpretation. Mainz, Schott Musik International, 1996. 114.