As musicians living at this moment in history, there’s no way around the enormous legacy of repertoire that Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) left us with. For most of us, it was at the basis of our early music education and it grows with us, as the never ending work of progress Bach is, as we evolve as musicians. But, who was the man behind this complex, yet deeply emotional music? Who managed to create music that inspired generations of people and still does so up until today?

Little information about Bach’s private life and personality is known, unlike the enormous amounts of knowledge we have about his works. Thorough research has been done by many and has led to some very educated guesses based on letters and records of the time, yet it must be acknowledged that because of the lack of factual information existing, the elements discussed in this chapter are often deductions or highly likely assumptions made by researchers.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach in a family of musicians that went back generations. From the start of his young life, Lutheran faith played a big role in his life. It was a big part of society during his time as well as of his early education. There are stories of terrible situations at his first schools concerning terrible punishments such as corporal punishments and threats of eternal damnation for bad behaviour such as bullying, sadism and sodomy as well as rumours about abuse. We also know about a sadistic disciplinarian teacher, cantor Arnold, of Bach, that was known to inflict unbearable punishments on his students.1 Even though the situations at the schools were horrible, we know through records that Bach was a relatively good student. This, however doesn’t mean that he was exemplary when he was younger, as there are stories of Bach and his friends at a local pub, drunk and slashing with their dirks and hunting knives. The turbulence of his early school time combined with the loss of both of his parents at the age of 10 are bound to have left a mark on him.

Grief was something that surrounded him his whole life, being orphaned so young, losing his first wife as well as 12 of his children before the age of 3. It’s believed this was reflected in his music, making it more human and more grounded than the standard lively energetic music of his contemporaries, such as Händel, due to it being closer to reality, including both the joy of life and the grief of death.

During his life, for most of which Bach worked at churches and courts, his Lutheran faith continued as a red thread. Even though his work required him to mass produce new music, Bach never approached this as writing a quick work accompanying the religious texts. He rather made intricate musical stories around it, lifting the already existing text to a new level. His approach was never neutral, it always opened up a world of emotion, sometimes adding strength to the words as well as negating the text and overruling it with the intensity of music. All this while keeping a clear and concise structure and exact mathematical proportions staying close to the clarity that his deep religious conviction provided him with.

Bach however, was not just active in church life but also in the social life (like the social circles of the musical Café Zimmerman in Leipzig).2 In this, we can see that he was not only writing more serious works but also simply writing for amusement, in some works we can even see a wink to either side as these two worlds intertwined.

Putting Bach in the historical context of his time, we have to take into account the Enlightenment at the beginning of the 18th century.3 The Enlightenment, standing for ‘the Age of Reason’, was a time between 1700 and 1800 during which science, philosophy and politics came more to the foreground, causing people to question the truths that before were completely defined by their religion. This movement added reasoning to life and to the general approach to religion. The connection between this time and the yearning for returning to reason and objectivity at the beginning of the 20th century, which will be discussed more in detail in one of the next chapters, is an interesting one to draw as it creates a parallel to the time Hindemith grew up in. However contradictory it may be, during the time of Bach, Germany “leaned” into the side of theology, at least concerning the performing arts. This meaning that they chose to focus on the more reasoned developments happening in religion, rather than focussing on the scientific and philosophical revelations that could come of the movement. A consequence of this was that during Bach’s time music still continued to require that art have an explicit moral, religious or rational purpose, not yet giving any importance to aesthetics and beauty like the tendency starting from the second half of the 18th century.

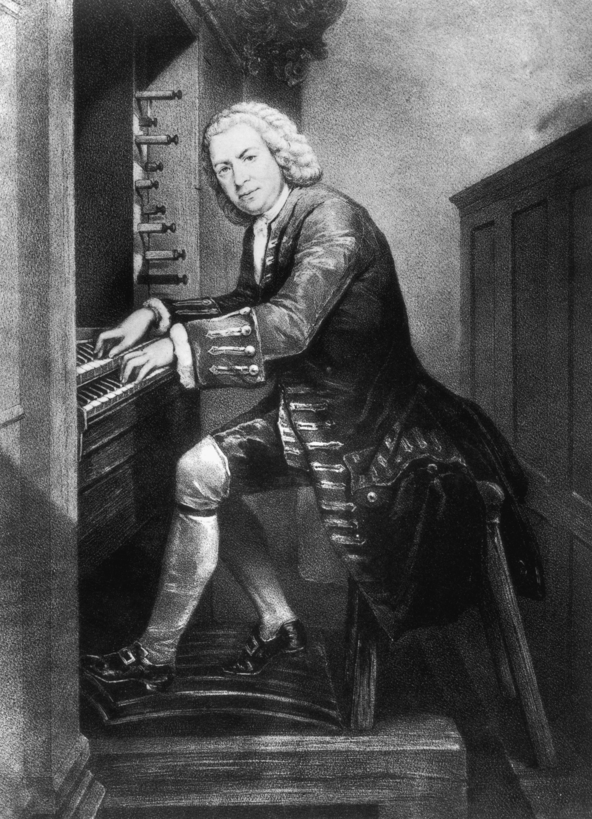

Bach’s mastery as a composer was because he was an autodidact, learning by detailed studying of works of the most capable composers of his time. Next to this he was also an extremely skilled organist and instrumentalist as well as a teacher.

Throughout his life he was known as a serious, devoted and hard-working man that strongly valued his artistic autonomy, which often caused him to have conflicts with his employers.4

The theme of life and death was one that followed him to the grave, still prematurely losing more of his children during his lifetime. Many of Bach’s late works include this dichotomy between a world full of misery and the hope for salvation. To Bach, as derived from his cantatas, music gave him a glimpse of life in heaven while offering him a weapon to protect against the fear of death. To us, his music can be seen as the voice of God in human form.

Even though Bach was an esteemed, but never famous, musician during his time, after his death most of his music remained unpublished and unperformed. The name Johann Sebastian Bach only re-entered the stage when Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) conducted the St. Matthew Passion in Berlin about 80 years later, after receiving a copy of the manuscript as a birthday present of his grandmother. Thus, unknowingly opening up the world for the legacy of J.S. Bach.

Bach’s view of the world, so influenced by life and death, grief and religion, made for a real human. However I noticed that he used all that emotion, all that life experience, while still keeping a kind of formal distance from it, an almost objective view as if another person was telling Bach’s life story. This objectiveness, this clarity, never clouded by extreme emotions, is typical in his music and is something that we can recognise in Hindemith as well. Their strength in expression came from their absolute strict forms and rhythmical patterns, each element adding strength to the next without ever straying from the path with its clear goal. When connecting these two pieces in performance, it will be one of my main aims to focus on building up the music from these elements and drawing the expression from them.

[1] Gardiner, John Eliot. Bach: Muziek Als Een Wenk Van De Hemel. Amsterdam, Netherlands, De Bezige Bij, 2014. 221-223

Huizenga, Tom. “Bach Unwigged: The Man Behind the Music.” NPR.org, 29 Oct. 2013, www.npr.org/sections/deceptivecadence/2013/10/25/240780499/bach-unwigged-the-man-behind-the-music.

Alberge, Dalya. “Revealed: The Violent, Thuggish World of the Young JS Bach.” The Guardian, 2 Dec. 2017, www.theguardian.com/music/2013/sep/21/secret-bach-teenage-thug.

[2] Motto Cosmos. “Personality of Johann Sebastian Bach - Unique Thesis - by Motto Cosmos.” MottoCosmos.com, 22 Feb. 2021, www.mottocosmos.com/personalities/personality-of-johann-sebastian-bach.

Gardiner, John Eliot. Bach: Muziek Als Een Wenk Van De Hemel. Amsterdam, Netherlands, De Bezige Bij, 2014. 311, 319, 324-325

[3] Gardiner, John Eliot. Bach: Muziek Als Een Wenk Van De Hemel. Amsterdam, Netherlands, De Bezige Bij, 2014. 70

[4] Gardiner, John Eliot. Bach: Muziek Als Een Wenk Van De Hemel. Amsterdam, Netherlands, De Bezige Bij, 2014. 209-210