5 Ironing Stories

In this lyric essay, we rely heavily on memory, particularly in our discussion about ironing. All of us learned to iron when we were children and wrote our recollections through a nostalgic lens. Some of those memories were fond, others bitter. But memory often serves to distill one’s feelings and it plays a strong role in our narratives about ironing.

If the steep learning curve of the VR forced us outward to consult a range of online sources, our collective reflections on ironing do the opposite. Here, we tap into individual memories of learning, which are often entangled with teachers, parents, and community members. Unlike digital learning, our understanding of ironing came from observation, social expectation, schooling, and relentless practice. The writing is personal and reflective, pointing to the informal ways in which learning occurred and allowing us to ruminate on our own lived histories.

5.1 How do you know how to iron?

by Lynne Heller & Tricia Crivellaro

LH—Ironing is deeply satisfying. You start out with this wrinkled, wretched, bunched up cloth and through ironing you can wrangle into a smooth, crisp piece of clothing or table linen. I think my sense of order is restored every time I iron. It is also something I can’t rush. Linen fibres in particular will only straighten out with time, water, weight, and heat. And then you have to wait until it is completely dry and flat before the miracle of ironing happens. It can look like a wrinkle will never come out and then you lift the fabric off of the ironing board and you can’t see it anymore.

TC—Using steam while ironing is truly the essence of solace and quiet enjoyment. The comforting hiss of the water as it evaporates, and the gurgling water. I often forget that steam is hot and dangerous and I put my arm where I shouldn't and I end up with a burn—the downside of steam!

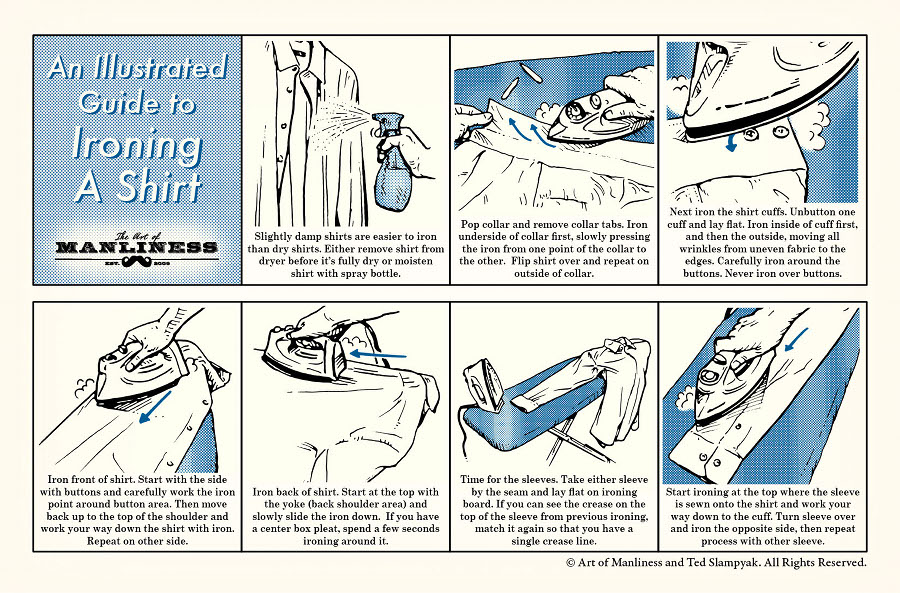

LH—The worst is when you accidentally iron in a wrinkle. Those wrinkles are the most stubborn to iron out! They persist as a reminder of humility in all things ironing. Particularly when ironing shirts with sleeves. Manipulating the sleeve on the ironing board means that folds and wrinkles happen inadvertently and you almost always iron in one of the folds you have created by trying to get into the difficult and small areas of the shirt.

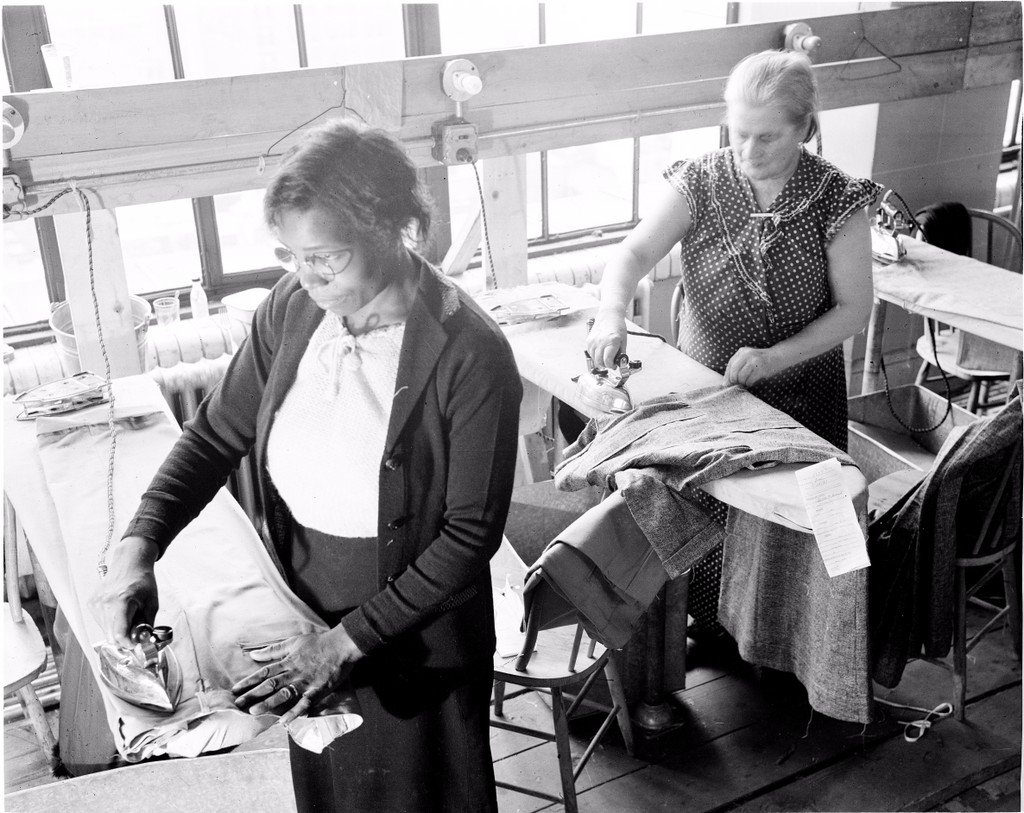

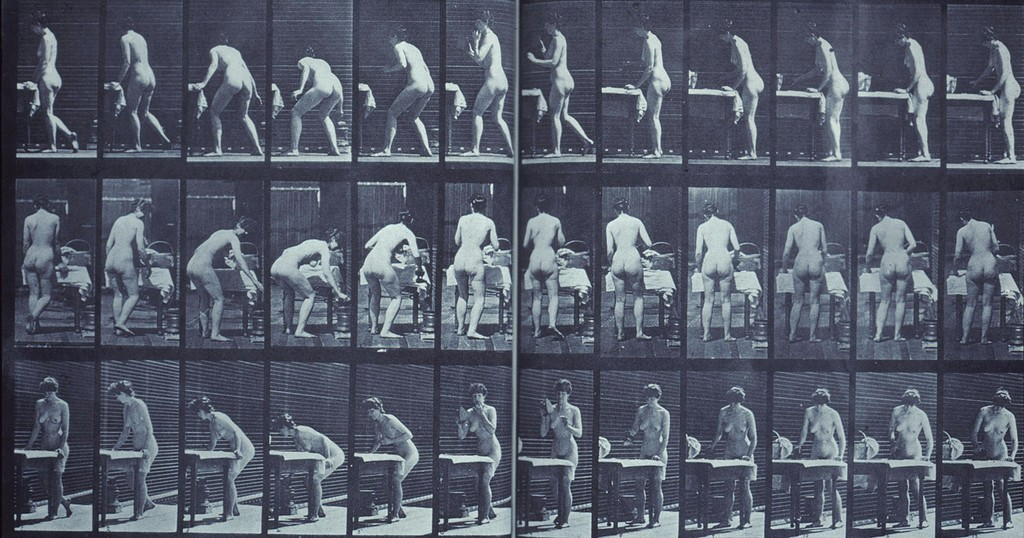

TC—You need to use your whole body when ironing, specifically with the heavy and industrial irons. Once skilled at it, you act on instinct and the manipulation of a garment on the plank takes on a rhythm, becoming a sort of unconscious dance, rigid and controlled, but with gracious maneuvers. It is captivating how everyone builds their own steps and ironing routine.

TC—And also the use of the wrist to skillfully manipulate the iron itself—the tensed but strong arm to hold the tool—and the delicate use of the other hand and fingers to precisely manipulate cloth beneath the iron’s tip. I could go on and on…

LH—Not all irons are created equal. When I’m ironing with a bad iron, I’m in a bad mood. Light irons don’t work so well, they feel insubstantial and don’t give you the sense that the iron is working at all. Irons that are too heavy are hard to move around. Like Goldilocks, I need just the right weight.

TC—I love the engine, the 'machinesque' aspect of the iron itself. I have to admit, I have a preference for industrial irons. Its metallic and utilitarian design, the front curved and pointed tip, the so-rare, sturdy, wooden handle, and the slinky cord that maintains the iron to the board, allowing for agility and rapidity of use. The weight of the object can become a burden for some but the added pressure the iron puts on fabric is a pure and powerful feeling.

LH—Irons that have residue on their plates are the worst offenders. Ironing in a wrinkle is not great but usually fixable, ironing gunk into cloth using heat and pressure is often a lost cause.

TC—When assembling a garment from scratch, it is particularly important to iron all along, at every step of the process. The precise and self-developed order in which you decide to iron a piece of clothes is critical to one’s method of assembly. The ironing masters of the fashion industry often do iron at the end only—I am in awe of their elaborate technique.

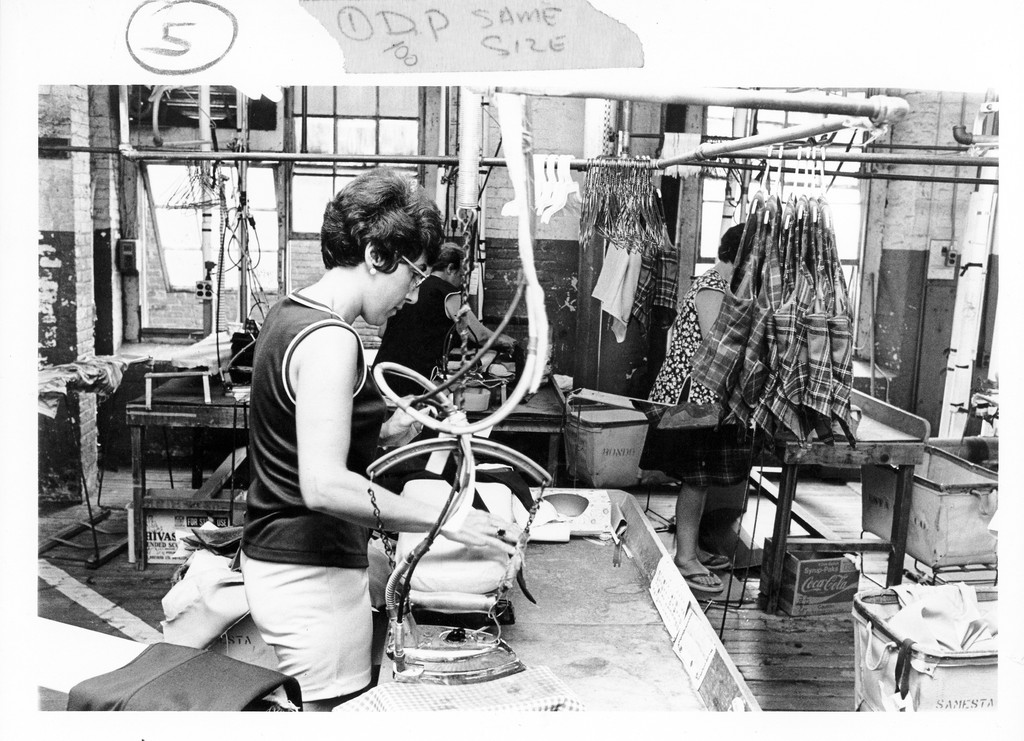

TC—I remember those hot summer days spent ironing in cramped fashion studios during stressful production runs. As much as I am an iron lover, I completely hated those periods. Most ateliers don’t have AC—sometimes not even a fan—and it is just hell. I have no idea why I would always end up being the lucky one behind the industrial plank…completing the ironing job became a total cardio work-out where you’d end up drenched in sweat and tears. At that point, it was more of an exercise in endurance than a zen activity.

TC—I recall a student who decided to use an iron as a creative design tool. They purposefully but intuitively created ephemeral pleats firstly on the fabric, and also at the end, by adding some on their garment as well—what an innovative explorative technique.

TC—Ironing a cotton muslin prototype. I still can’t quite explain why an ecstatic feeling comes over my body when ironing that specific fabric, but I think it is related to the feeling of being a student. Still to this day, when tenderly placing muslin over the plank and under the iron, I relish the first few seconds where I’ll be brought back in time to those long and exciting years of learning garment-making.

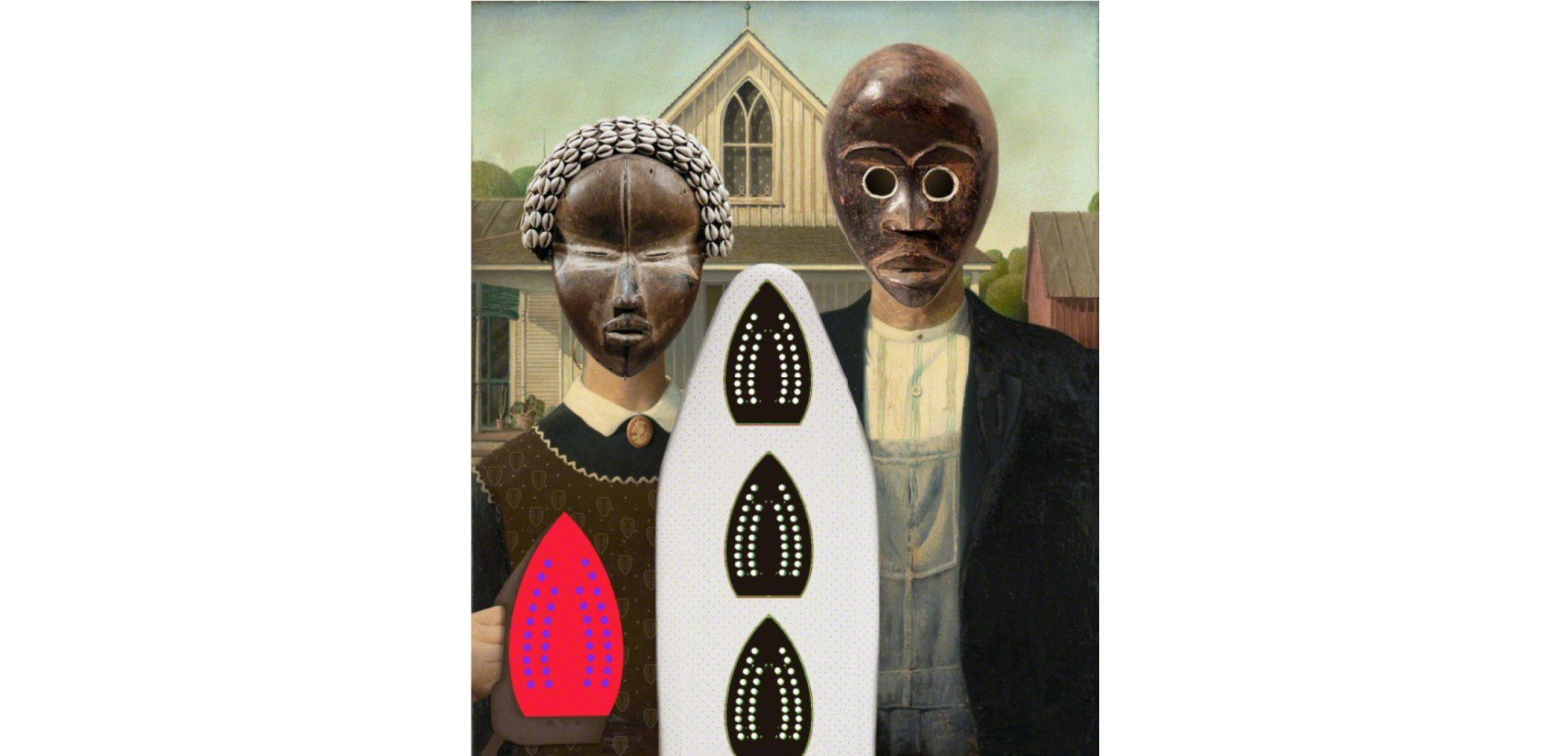

TC—Perhaps ironing conjures domestic imagery in the minds of most—those prosaic practices of everyday life, like washing the dishes, folding laundry. Then again, it reminds me of the movie Beau Travail by Claire Denis where ironing takes on an aspect of military routine. I am referring to the scenes depicting macho, well-muscled, half nude legionnaires ironing their clothes with exacting precision. Here, garment maintenance is imbued with a sense of discipline and importance while being presented with an aesthetic value that is almost sensuous in its gracefulness.

5.2 Ironing by Lynne Heller

I was ironing a bedsheet. Ironing has an imposed pace. It is intrinsically slow and you need to find patience and tempo to do it without frustration. It just takes time to iron something flat and dry and there is no rushing it. So I spent the time while ironing the bed sheet wondering. Would one have a better sleep if you went to bed with a sheet that was ironed? I decided yes. It has to do with my love of aesthetic order, sensual engagement and the fact that someone cared enough to iron the sheet. The idea of caring about details—even though people perhaps don’t necessarily perceive them—comforts me. It is a wilful belief that I don’t ever really want to test. I just want to believe it.

The humidity and smell of ironing is an overwhelmingly sensual experience. Going into a laundry in winter is warm, steamy, and enveloping with the smell of clean flooding your senses.

VR worlds excite our eyes and ears but are impoverished environments for temperature and scent.

When I was young, laundries in Toronto were the purview of Chinese immigrants. They would often have tropical plants in the windows because the humidity and warmth of the washing and ironing process was so conducive to growing. I have a strong image in my mind of a cleaner’s storefront, wood trim painted in a certain green colour considered typically Chinese, with black lettering with red highlights written on the window in Chinese and in English. The top part of the window would be fogged over and the bottom would have all the thriving plants lined up. I have a memory of these places being on lonely stretches of main streets. But I’m romanticizing them. They were sites of hard work under tough conditions. Other than Chinese food restaurants, operating a cleaners was one of few other ways for immigrants to make their living in Canada.

In “Occasional Toronto: Last of Its Kind?” blogger RedPat writes about the Chow Keong Laundry and Cleaners as “probably the last of the hand laundries in Toronto” (Redpat). The original proprietor, Chow Keong, arrived in Canada in 1921 at the age of fifteen and worked at one of 374 Chinese laundries in Toronto at the time. He opened his own laundry in 1946, originally located on Elizabeth Street, he moved the store to Avenue Road, just north of Davenport Ave. In 1952 he sponsored his son, Dennis, to join him in Toronto. Dennis, now in his 80s, still works in the storefront laundry (Leblanc).

Artist-curator Shellie Zhang contends that the “location of the former and current Chow Keong Hand Laundry marks a shift from the perception of hand laundry as a lowly and unclean occupation to a now near luxury service that perhaps only few in Yorkville can afford” (para.8).

Chinese laundries were ubiquitous from the 1920s throughout North America as immigrants sought a means of making a living in extremely limited circumstances and in the face of unrelenting bigotry. By 1921 over half of the Chinese residents in Toronto were estimated as being involved in the laundry business (Lee). Historian Arlene Chan suggests that “the laundry business was not so much a choice but a response to what was available” (loc. 624). Laundry was not a traditional household task for men in China where it was considered women's work (loc. 617). The association of laundry and by extension ironing as feminine was well established and the relegation of this work to Chinese immigrants emasculated Asian culture in the eyes of Canadians of European descent.

5.3 On ironing by Kathleen Morris

Two snapshots of ironing: In the first, my mother stands with a laundry basket of my father’s linen handkerchiefs at her feet. The ironing board is set up in the living room, an episode of Star Trek on TV. Watching the show may be consolation for the endless slog of domestic chores that she understands her life to be. As a child, I see it as a curious ritual, a pile of handkerchiefs neatly folded and stacked into perfect uniform squares as the episode unfolds. Captain Kirk boldly going where no man had gone—my father doing very much the same, forging an upwards path to unknowable galactic heights. My mother planted down on earth, fuelled by simmering resentment for the expectations put upon her. The expectation to be home with her young daughters, to deny her professional ambitions, and to be standing at an ironing board, creating a perfect stack of uniform white linen handkerchiefs.

The second snapshot is of my son ironing his denim button-up shirt using the cotton steam setting. A bath towel is folded on the dining room table, and he irons the shirt strategically in sections, iron gurgling and steam rising from the table like a cloud. He is mesmerized by the iron’s power, asking family members to bear witness. “Look mom. No steam—then steam!” We all attest to the dramatic transformation in the shirt. He imagines possibilities for the iron, removing wrinkles from any substance imaginable. A wondrous tool of infinite potential.

The snapshots depict temperaments writ large—the act of ironing unlocking the respective natures of my mother and son. The disciplined resignation of my mother’ weekly chore was matched by the sense of unbridled possibility in her grandson. It also casts the spotlight wider on the societal changes that have unfolded over the decades between them. Ironing was one of many duties that exemplified my mother’s servitude to the family. Whether undertaken with grace or reluctance, it was nonetheless required. My son’s enthusiasm stems from the job no longer being gendered, nor indeed expected at all. To him, the iron was a novel tool, ripe for experimentation, not a prescribed task.

The tools we use say much about ourselves as well as the worlds we inhabit. In the domain of textiles, the obligation to sew, repair, launder, and press clothing defined the post-War decades for Western women like my mother. Ironing obligations have waned thanks, in part, to a proliferation of wrinkle resistant fabrics and the evolution of social norms. The servitude of other apparel work has largely been divested to the global South, subjugating new gendered populations through unvalued labour. The torch has been passed, yet the oppressive constraints of textile work prevails. It raises the question: Do we need to be comfortably detached from a tool or chore to embrace it—to revel in the cloud of steam from the iron? Perhaps we need to recognize that paying tribute to the act of ironing is predicated upon a level of societal and economic privilege, one that enables us to romanticize manual labour and see the infinite possibility in tools that we are no longer obligated to use.

5.4 Ironing by Shiemara Hogarth

I went to Catholic schools for my entire prep and high school education that came with uniforms heavily pleated that I had to learn to start washing and ironing since I was around 10. It was always drilled into my head that this was something young girls needed to know how to do. Each weekend I would wash my uniforms by hand, hang them out on the line to air dry, and when they were done drying, I starched and ironed all five sets of uniforms for the upcoming week.

In the past seven years or so, I have been more conscious about having more sustainable and ethical practices around clothing and what is in my closet. I have been needing to iron a lot more. I have never approached ironing with joy, but I gained capability from an early age by necessity. However, I have noticed an ongoing reticence to the mere thought of ironing, to the point where I find myself trying to calculate if I 'need' or 'just want' to wear 'those Tencel pants', or 'those linen blend shirts'. There is an immense satisfaction once I see them hung up when I'm done washing and ironing them. They are beautiful garments. They feel amazing on the body, and I know I wouldn't wear them without ironing them because that would feel like a complete disservice to the garments. I also genuinely would not want to be seen in excessively wrinkled clothing. But that knowledge doesn’t ever quite stop the slight pause I have before I reach for the iron and ironing board. I know this feeling is a holdover from the fact that ironing was drilled into me as a very gendered act from a young age, and I have never been comfortable with this being the status quo, especially knowing that, as one of three siblings, I was the only one given this responsibility.

I think about my aunt who recently passed away and was a housekeeper for most of her adult life. One of the main things she did was to launder and iron clothes. I never had a chance to talk with her about her feelings about her job, but I do remember she spoke fondest of kind employers. I can't speak for her, but I assume that something that was her primary source of income probably wouldn’t be easily defined as love. I also think of my very Gen Z niece, who times the clothes dryer, so that she can take her school uniforms out mid-cycle and hang them to finish drying, letting steam and gravity do the lion’s share of the work. She has no intention of ever ironing any item of clothing, and I will absolutely not be the one to force her to do that if she doesn't want to.

The fibre work in my studio practice is an anomaly to this feeling of reticence because it feels like an absolute necessity in doing my work properly, and it is mentally removed from the association of that previous experience with the body. If I am quilting, the process requires that I iron to have the stitches set into the fibres of the fabric properly at each step. If I weave something, I have to steam it afterwards. I am meticulous about this—possibly because the outcome of the ironing is something that's not associated with a thing that I'm feeling forced to do. Working in fibre is heavily gendered but the personal association to the 'why' behind the labour definitely seems to impact how I feel and approach things differently when they are removed from my body.

5.5 Ironing by Dorie Millerson

My parents were compulsive ironers. The board was always up, blocking the door. My mother ironed; my father ironed. The shhusssh of the steam, a constant sound. No wrinkles on their clothing. I have no memory of being shown how, just of watching and trying. Then, in my twenties, someone showed me how to position a shirt on the small end and then the big end of the ironing board, passing on lessons from his mother. I had never considered the shape of the board. How to arrange the collar, the shoulder, lining up the sleeve, the precision of creases. The power of the iron was revealed, the potential, the need, the perfection.

These days, I teach others to iron. I comment on the lack of ironing in their work. I explain the importance of temperature, fibre, the ever-present risk of damage. I look up to see if it is familiar. Perhaps they have only watched, perhaps they have never been shown, perhaps they do not yet see the need. We learn more from being shown how, than from merely watching. What is the difference? An active engagement with the importance of what we are seeing. A tool can’t be used well until we understand how to use it.

Watching demonstrations of tools is a big part of learning to make textiles but it is only the start. To become fluent in the use of a tool, we practice over time to attain dexterity. In viewing the work, the tool disappears. Only the complexity of the structure or surface remains. As for the invisible work of ironing, it is only visible in its absence.

5.6 Ironing by Pablo Montenegro

Burnt saliva. It’s a smell that instantly transports me back to my childhood. Frankly, I thought the smell was curiously repugnant, but like a good spectacle I could not keep my eyes off of what was in front of me. My grandpa, Papito Hugo, would wear a perfectly pressed button up every single day, and as such, part of his daily morning ritual was to choose said shirt and iron it, beautifully, carefully, with intention. And his daily ritual inevitably became mine as well. I would peer over the wooden table he had beside his bed, one that was covered with a thick off-white poncho. I’d watch as he’d put a generous amount of saliva in his middle finger and quickly tap it on the base of the iron - 'TSSS-TSSS' and the unforgettable smell of incinerated saliva were the signals that the iron was ready to go. I watched as the musky liquid quickly evaporated off the hot metal, setting my grandpa off into a focused effort to smooth the garment atop the table, directing his hands across the cotton, forming the path behind which the iron would follow, laying the wrinkles to rest. The competence of the movements he had perfected over the decades transfixed me, which melded perfectly into the scene he was creating, one where a transformation was taking place as he was turning himself into the elegant man I always knew him to be. Indeed, not only was there an atomic, physical change occurring to the fabric as the wrinkles were no more, but also a personal, non-physical transformation was taking place in the way my grandpa viewed himself; the ironing process was the start of a ritual where he moved from his private life into his public persona. I remember one of his sayings was: “como te veo, te trato” which translates to “how I see you, i treat you”. For him, public image was always important because his livelihood depended on it. He was a merchant and often traveled to different cities to buy a variety of goods he would sell out of his store, so portraying a sense of trust and a level of class to his clients was crucial, making the suit and a tie the uniform of his choosing.

And these are precisely the memories I have of him, as someone who deeply cared about how others viewed him, perhaps to a fault, but with a sense of honor and grace that is worth emulating. I mean, it never seemed that for my grandpa ironing was an inevitable annoyance to getting dressed, but rather a precise craft ready to be perfected. It seemed that for him being well groomed and dressing elegantly was honoring the social contract; that he is a part of a society that works under certain social agreements, many of those stylistic rules that we must follow if we want to function properly within that society. Unfortunately, within the discourse around “mestizismo”* that was occurring in Ecuador in the 1950s, there's a line of criticism that can be drawn if we see my grandpa taking up the western suit and tie as the de facto form of portraying class and social power as an erasure of the indigenous part of his cultural heritage. But the reality on the ground is much more complex and intertwined than this. When I go back to Ecuador I try to pick up on stylistic cues that might point to how foreign influence melds together with our local garb, alway managing to leave inspired by how people are able to interweave them together. Often they wear their long braid with a suit, a poncho over a button-up, or maybe some dress pants and their traditional shoes. From this point of view, we can see my grandpa taking up the suit and tie as his uniform not as a complete erasure of one part of him for the other, but as an opportunity to create a fabric of creative tensions between these two strands of him. And weaving such a fabric requires a give and a take, so he wears the suit and tie, but still wears his felted hat; he wears his dress pants and dress shoes, but still talks Kichwa as much as he can. And herein lies the connection to ironing, a process that sees the garment as a fabric of creative tensions itself, a place where the reality of wrinkles is interwoven with the need for irons, and an emphasis on the ritual that brings these two together.

Another way of thinking about it is that ironing is a metaphor for the inevitability of change. That is, with change, the thing we know for certain is that it will come again. Similarly, with wrinkles, the thing we know for certain is that we will have to iron again. Both are inevitable, iterative processes, and that is precisely wherein their beauty lies. Like a craft ready to be perfect, changing with grace and ironing our clothes takes time, effort, and intention. Both give a sense of agency back to our lives, reminding us that we choose who we want to be, and how we want to be, while constantly transforming, evolving, wrinkling, flattening, loosening, and tightening. Burnt saliva comes to mind again. This time I am remembering my grandpa explaining that wrinkles are easier to iron if the fabric is damp. Being low-tech as he was, his solution was to have a half-filled glass of water at the table he would sip on and blow onto his clothes. tss-tss would sound as he passed the iron over his thick cashmere pants, the notorious smell not too far behind. I can feel it all so well, still. Just as I feel the canyon of time that seems to exist between who I was then and who I am now. But I am reminded that my past, present, and future can also be intertwined into a fabric of creative tensions, and I choose to do that as I speak of the deep legacy my grandpa has left in my life through the lessons he has taught me, many times over that wooden table where he would iron his clothes.

Britta Viggh, Swedish immigrant in Nicaragua

Rivas, March 15, 1891

“We still live in the same place as when I last wrote and I have plenty to do. A lot of starched shirts are worn here, and as the pay for a well-ironed shirt is quite good, I have started to do ironing for certain people. For one shirt with collar and cuffs I get up to 25 cents, in Swedish money 75 öre. When I have finished ironing one shirt I have paid for the day’s food. On account of the heat, I don’t have the strength to do a lot of ironing, but it still helps out. There is no one here who knows how to iron to a fine shine, if I can call it that, and now the whole town is curious to find out how I do it and I take all precautions so they won’t steal the art from me as I would then lose my earnings. There I only wish I had a Swedish girl here to help me.” (Wettre 131).

Page 6 Conclusion