3.3 Un/learning Methodology

Whether consciously or deliberately, there is a need to unlearn approaches in the digital and physical environment when switching between the two. Their respective tools and approaches may be well-suited for a specific type of making, but not necessarily transferable. Just as we can readily undo mistakes in the digital environment that we cannot in the physical realm, we are often in dialogue with material in the physical realm, responding to its needs and affordances in real time in a way that is not neatly aligned with our digital work.

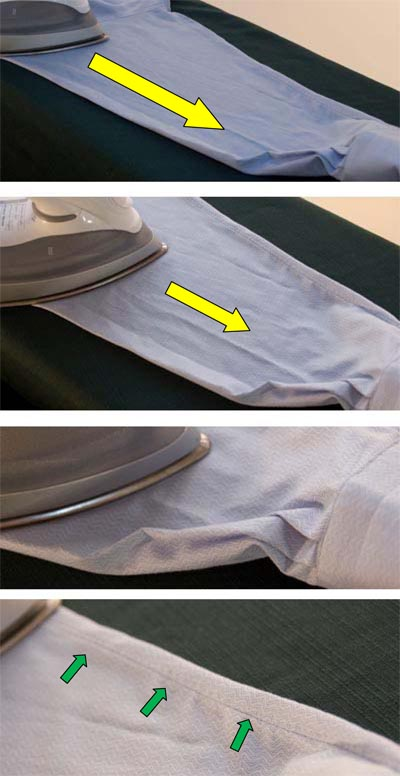

Craft methodology imparts a keen awareness of materiality and the distinct material properties of the work being made. We learn about materials through careful handling, use, and accumulated knowledge. A learner quickly understands that a woven hemp cloth will be as unsuitable for a soft flowing garment as a silk chiffon will be for sturdy workwear. The deep-seated lesson learned when working with physical materials is that it is possible to overwork. When ironing, if you iron too much the fabric can become shiny, burnt or stretched. Restoring the quality of the original textile is impossible. It has been changed forever. The change can be integrated into what you are making, but the original state is irretrievable. In craft methodology, this sensitivity to material properties and judicious handling of materials is central to an understanding of making.

Working digitally, you have the magic of Command Z, the undo button, something unavailable at the ironing board, sewing machine, or serger. The tendency when working between the two is to wish for the 'undo' that digitality trains you to use. Compared to the confines of working materially, digital files are considerably more malleable, easy to adapt, and readily stored. Freed from the material confines of executing an artwork, digital materiality supports risk and multiple iterations of a design. While it would be inaccurate to claim that digital files are consistently reliable and error-free, we are nonetheless able to manipulate work in a way that is not readily available in material form.

3.4 Tools

Traditionally, the quest to maximize the efficacy of labour and mechanically reproduce hand skills has been the impetus for technical innovation. It drove the digital revolution through the work of Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace in the mid-nineteenth century. Lovelace made critical connections between Jacquard weaving—a digital process using punch cards to weave complex patterns—and Babbage’s counting machines. It was Lovelace’s theorization, although overlooked in canonical histories of computer development, that predicted the digital revolution (Evans Loc 340).

Craft has always been intimately connected to technology; however, in crafts-based making the emphasis on hand/eye/ear coordination leads to an embodied approach (Koskinen et al.; Nitsche et al.; Groth). In contrast, working digitally, sometimes outsourcing offsite and out of sight, raises questions around agency and autonomy—critical tenets of craft theory.

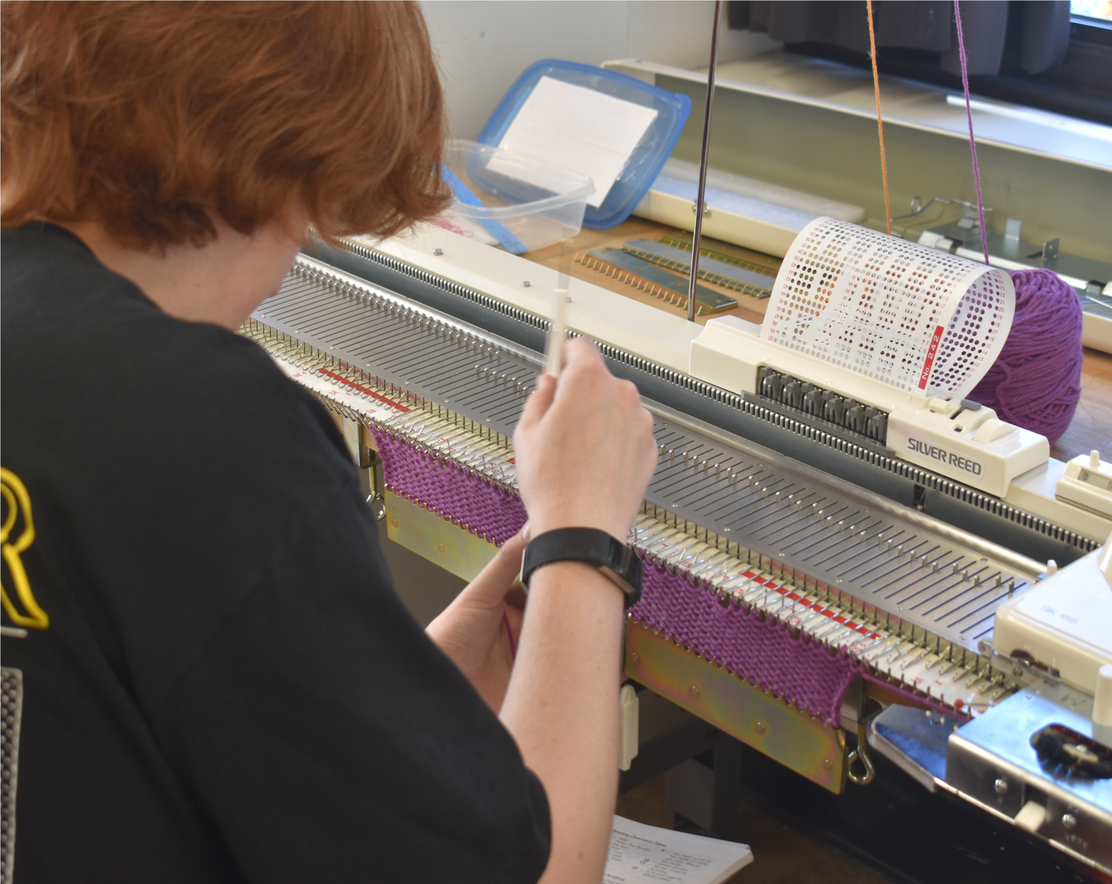

Tools are the lifeblood of craft, whether they be digital, manual or mechanical. Tools, like materials, guide and even dictate what you make. What you weave with a backstrap loom is substantially different from what you can produce with a Jacquard loom. Frequently throughout the process of developing this project, we have asked ourselves: “Do we feel differently about digital tools than we do about manual or mechanical tools?”

We think yes.

A tool that we use in traditional craft is often one that we grip, hold or mechanically operate with our hands, feet or mouths. Digital tools for the most part imply tapping on a keyboard.

Digital tools, due to cost, complicated operating instructions and/or safety are often placed at a distance from the maker with a technician in between. Sometimes they are outsourced, which creates even more distance and puts into question authorship and agency. Who is the maker? What is the maker?

All tools leave their imprint on the body. Muscles, tendons, cartilage are all continually strengthened through repetitive action as well as being weakened at the same time. Leaning over a jewelry bench many hours a day or throwing pots on a wheel daily makes the body stronger in some ways but sets the maker up for repetitive strain injury. In contrast, typing on a keyboard and hours looking at a screen have stealth impacts on our physicality. Posture, eyesight, and wrists are all affected over time, making our current means of interacting with digitality an insidious health hazard.

A computer is a bottomless tool box. The algorithmic nature of digitality means that it can be reconfigured to do myriad tasks. As a maker working with digital tools you interact in the same way using a mouse and keyboard, but you can create very different outcomes. The skill required to 2D print on fabric isn’t significantly different from 3D printing a pot. Digital tools are mysterious, hidden away in a generic box, the software controlled by anonymous programmers, the hardware designed by unknown engineers. Digital tools can seem impenetrable, lending them a mystique of power.

In contrast, craftspeople know their traditional tools intimately. Often, they have even made the tools they use for their craft. Knowing how to create repeat designs on fabric through silk screen printing requires quite a bit of specific knowledge and skill, such as how to prepare a silk screen, knowledge of the viscosity of pigments, the touch needed to pull the pigment through the screen using a squeegee. Throwing a pot on a wheel takes years of practice to control clay and centrifugal force. These skills are significantly different and particular to what you are making.

3.5 Tool Consequences

Another less recognized impact of digital tools is environmental degradation. The life cycle of a computer is inherently short compared to mechanical equipment such as a loom or kiln. Sabine LeBel writes that “[e]-waste is the fastest growing waste stream in the world.” In our fetishization of digitality and the technological sublime “in which technology is seen as intellectually, emotionally, or spiritually transcendent,” we concentrate on utopic myths such as “the promise of ecological harmony” when the reality is quite the opposite (LeBel n.p.).

Craftspeople often revel in obsolete technology both for creative and practical reasons. A piece of equipment such as the letterpress can be seen not only to be more poetic but also more inexpensive and sustainable than its digital equivalent (Larned). The maker can maintain the tool themselves and know that they will have it for a lifetime of work. Tools, such as a favourite sewing machine, weaving loom or potter’s wheel are often handed down from mentor to student as heirlooms and legacies.

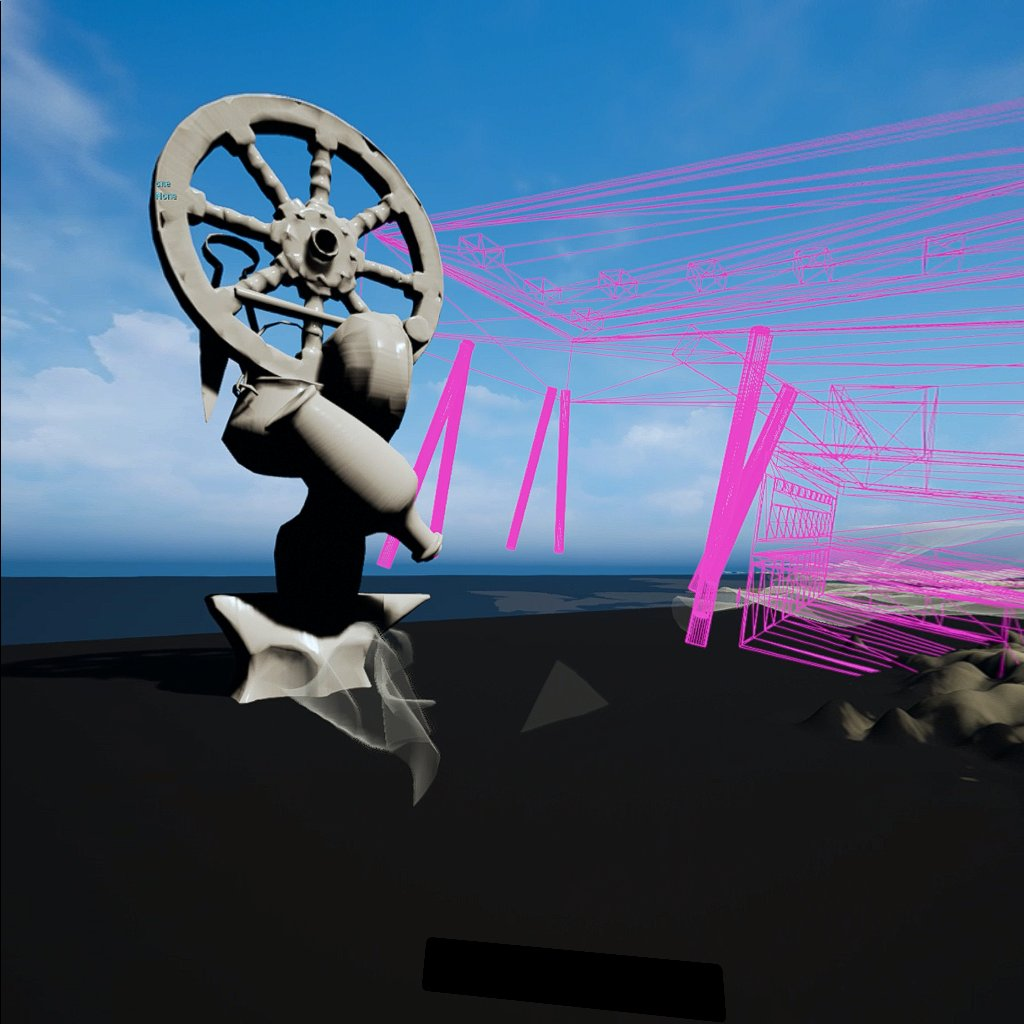

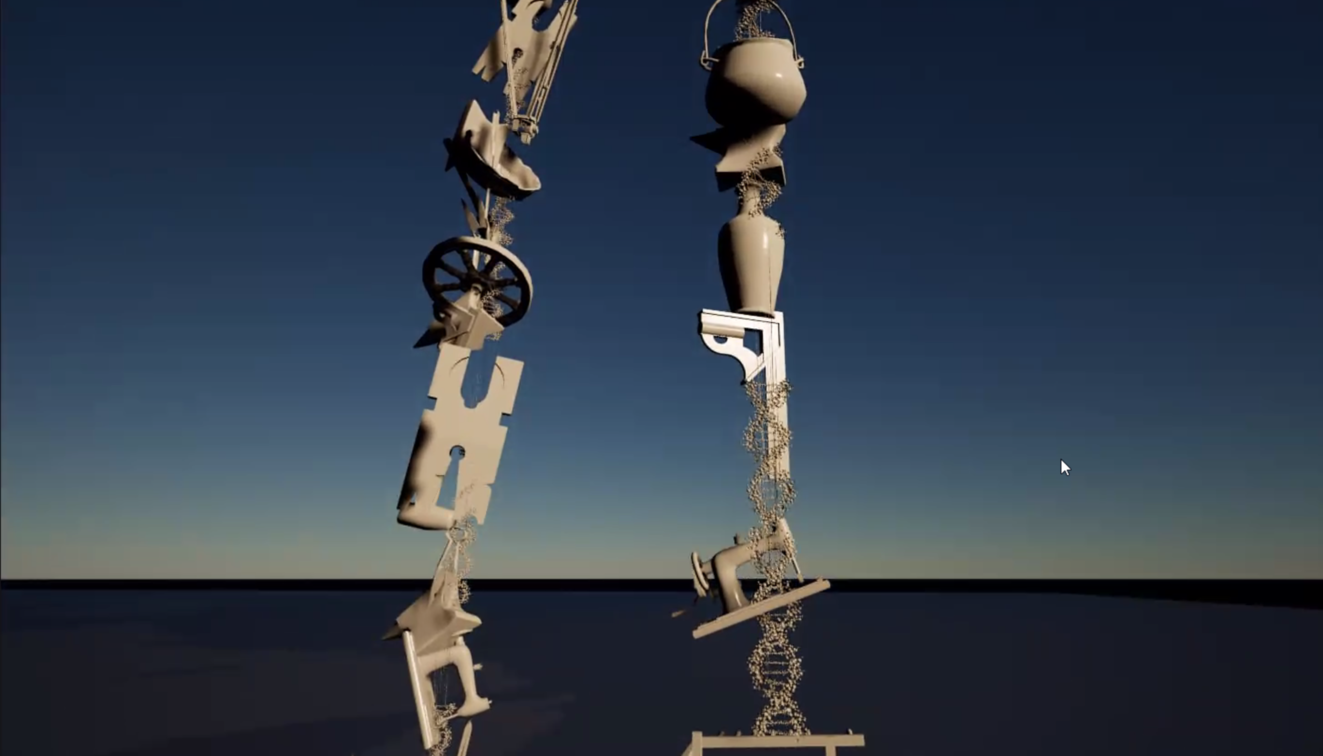

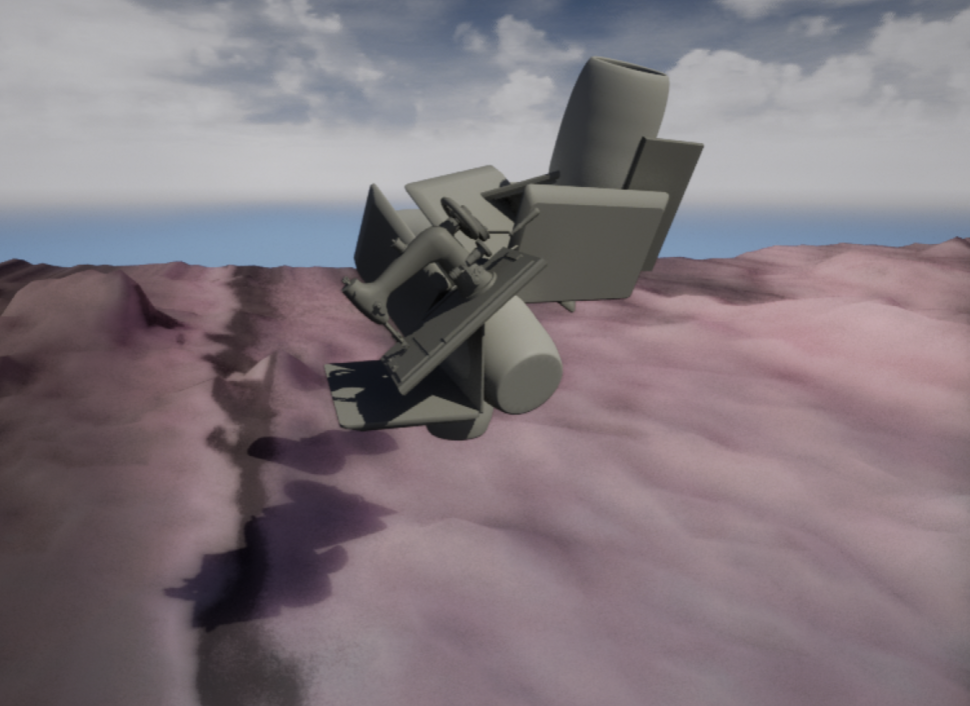

In the VR world we created, towering sculptures made up of tools dot the landscape, symbols of our criticality of equipment and devices. We mixed tools that we use for crafting—such as looms, kilns, measuring apparatus, spindles, pinchers, hammers, and bobbins—with tools for digital production—like keyboards, headsets, controllers, and headphones. We threw scale to the winds, sizing up or down enormous and tiny objects. We stacked them willy-nilly, playfully conflating, intersecting, and juxtaposing disparate artefacts. We stripped them of their material appearances, blanketing them with a beautiful but simple porcelain appearance. And in this way we signalled how attached we are to the tools themselves.

3.6 Vocabulary

It quickly became clear to us that we were fundamentally lost in this new world of game engine development. How do you learn without knowing the discipline-specific vocabulary? We had to rely on YouTube tutorials. In this Catch-22 world, in order to find the right tutorial we needed the vocabulary that the experts in the field use. Find the word—find the answer. Well, sometimes. We not only had to find the words but also assess the competence of the person delivering the information. YouTube authorities could be dubious, we found. Indeed, not all YouTube experts are experts.

Learning new vocabulary felt like taking baby steps. New words such as

exponential height fog

normal map

new world

world actor

chaos cloth

dynamic wind

world partition

were a foreign language for us.

On the other hand, words we thought we knew;

flipbook

float

baking

cooking

collision

material

texture

pawn

had entirely different meanings in UE5.

3.7 The Language Wall

The basic irrationality of language—'dog' signifies an animal but 'god' a deity—has birthed industries of communication experts, semiologists, ad writers, and TikTok influencers. We encountered early on in our VR explorations the irrationality of naming and jargon-inflected instruction. We marvelled over this new vocabulary that was uncanny in the true sense of the word: at once familiar and strange.

The language of UE is as obtuse as it comes but discipline-specific vocabulary is nothing new: the craft guilds of medieval Europe used specialized language to guard trade secrets, some adopting secret languages that could not be used outside their trade. Opaque, 'secret society' language is as old as language itself. It has always been a way to maintain power, to coalesce a group, to identify outsiders, and fend off industrial espionage by confusing competitors. Knowing how to use the right words at the right time is critical for people’s social status, livelihoods, and sense of belonging. The technical terms used in contemporary software adopt the long-established use of specialized trade terminology. The user becomes increasingly adept at speaking this language as they become proficient with the tools and processes of the discipline.

3 Un/learning

By learning, re-learning, embracing errors and glitches, and reimagining the Canadian landscape, we created a data visualization that offers a speculative framework for the future of craft in the digital turn. We return to Bergson’s understanding of knowledge acquisition in this process, and reflect upon the ways in which perception and memory synthesize new immersive experiences of learning.

3.1 Craft and Digital Learning

We come to this project as textile artists and educators, well-versed in craft methodology in which materials and processes are at the core. Learning in this context is both experiential and reflective, incrementally instilled in the body and mind over time as the maker is in dialogue with the material. Pragmatist thinker, John Dewey, laid the groundwork for our current understanding of inquiry-based art education. In particular, Dewey’s emphasis on experiential learning introduced subjectivity, consciousness, risk, and reflection as central to the process of artmaking. The ripple effects of this influence are notable in present-day understandings of craft. Sociologist Richard Sennett makes the case for craft being embedded in the practiced movements and experiences of making—an assertion that “we still live in a body rich in potential” (Metcalf 41). By this logic, learning has a visible and social dimension involving emotional and sensorial understanding (Shreeve et al.).

If the skills of making are acquired through experience and the “complicity of mind with matter” (Grosz 96), the use of digital tools calls into question whether and how their use affects the methodology of craft-based learning. Digital technology has been understood by some as not just a tool but a methodology in its own right (Marshall; Harrod); others have characterized it as a practice that encompasses sociopolitical structures and labour relations (Franklin). Digital tools and processes have altered the landscape for craft, prompting new conversations about pedagogy, authorship, authenticity, labour, and aesthetic outcomes.

3.2 Learning, Forgetting, Re-Learning

Working with game engine software to create a VR environment is considered to be a type of procedural learning. The nature of this kind of skills acquisition is task-based, such as adopting a keyboard shortcut or placing an object in the VR environment. Repetition is key in order to form procedural memories: ongoing practice and a stage referred to as overlearning are common methods that ensure the skills are not forgotten. Some theorists have pointed to the fragility of the knowledge acquired by a novice, who sometimes uses their skills correctly, and just as often does not.

For us, the steep learning curve of VR necessitated the overlearning of software skills. While a prolonged time investment is linked to faster performance, fewer errors, and greater competence, it is often a luxury. We found ourselves undertaking multi-stepped processes in order to achieve a desired effect, only to be stymied when having to repeat it several days later.

Importantly, even with the requisite practice, procedural skills require concerted and ongoing training over time to ensure they are retained. Given the brief, cursory, and transitory way many users engage with specific software—often a single program within a library of options—the retention of skills is elusive. It is unsurprising, then, that skills-specific YouTube tutorials have emerged as the go-to site for procedural learning.

How did we do that?

Lynne Heller (LH)–How do I do the screen grab in UE again?

Tricia Crivellaro (TC)–Windows Key + Print Screen?

TC–Windows Key + Shift + s

TC–?

TC–Screenshots you mean?

LH–(thumbs up)

TC–It works?

LH–in the oculus

TC–Do you want to Zoom? Share Screen?

LH–How we captured images for the PowerPoint

TC–I guess we need a protocol for screen capture

LH—Many months after presenting the VR piece, I wanted to capture a screenshot through the VR headset to send to another collaborator. I tried and immediately realized I didn’t have a clue how to do it because Tricia and I had figured out how to capture high resolution headset shots together. So I texted her with five minutes to spare, thinking she would just shoot back an instruction. She did but we were talking about different things—language again—I had used the phrase a screen grab rather than Oculus video recording. So she was puzzled because a screen grab is a simple thing to do if you are just on your computer.

BUT when you are wearing a headset and want a certain screen ratio it takes many steps rather than just one shortcut command. We couldn’t figure this out by text so we Zoomed. Even with more connectability through video I couldn’t communicate what I needed to know. Tricia had to come over to my house and we had to be together physically to figure it out again.

We had originally worked all this out the night before we presented the piece. We figured out the protocol by following good instructions which we had found through a search. The steps turned out to be quite complex. We kept our nerve and adrenaline focused our minds to accomplish this at the last minute. But when the adrenaline rush was over we completely forgot what we did. We hadn’t committed it to long term memory. We remembered vague snippets of steps. There was some sort of an ABS setting involved but we had no clue where we set it or why. Perhaps a bit of muscle memory was involved. I remembered that I needed to reach over the Oculus control deck in order to press 'disable' to get back to the pink bubbly space where the sharing was activated. But it was really hard to find the share button because it has an icon that is not a typical symbol. The memory of physically doing something, reaching over a control deck, was really strong but the steps themselves weren’t.

Fortunately, Tricia remembered that the person in the headset had to initiate the recording. I was convinced that Tricia did it on the PC, not on the headset. Tricia realized that we had actually recorded all our steps and we could watch the unedited video we took right before the presentation to recreate our workflow. Many hours later we had re-learnt. The real lesson being that it is better to learn something well the first time. But this is not a pedagogical truism I’ve ever been able to absorb. The excitement of learning sometimes undermines the purpose.

Learning to Learn

TC—Learn what you don’t know.

There is so much to learn that we don’t know what we need to learn.

What do we want to learn?

What should we learn?

We had to slow down

in order to contemplate and select what to prioritize—what is truly important and what is not. We wanted to understand every little tiny thing.

Reading too much and asking questions to each other,

explaining, re-explaining.

Amongst keyboard and mouse clicking sounds, as well as exasperated sighs,time is ticking and it goes backwards in an instant—we have a deadline, we learn and we forget.

There were moments while learning where frustration arose—no more researching, understanding, reading, theorizing.

We needed something tangible—to feel and touch, and make.

The only ‘tangible’ in learning are the tools, the objects, and the others, and the machines.

We tried to find ways not to forget what we learned, and then came the protocols.

To iron a shirt, one needs a shirt. Shirts made from natural fibres such as cotton, and certainly linen, usually need the most ironing. Since 1926, irons have had options for spraying water or releasing bursts of steam and a dial to control how hot the plate gets. An ironing board with a pointed end is helpful but in a pinch you can iron on a counter covered with a towel. A spray bottle with water is also optional but useful. And then there is starch. Starching your shirt will either make the fabric feel like a new garment all over again or make you a stuffed shirt. We remain decidedly neutral on whether you should starch your shirts.

Cost = at most, if you buy an expensive shirt, $300-$400

To create a VR world one needs an immersive headset. We are using the Oculus Quest 2. When we read this lyric essay in a few years time, this declaration will sound downright quaint. The Quest 2 has been the latest and greatest headset since 2020 but it is already being superseded by others with better screen resolution, faster refresh times, less weight, and higher comfort. You need a computer that has power. Headphones are optional but our composer thinks otherwise. You need a game engine. The two most powerful options are 'free' but not. As they say in the game industry there are 'in-app purchases'. They both have models for profit-sharing if you are making a commercial game. We used Unreal Engine 5.1 (UE). You also need to access other applications for 3D modeling, visual effects, sound production, video editing, and animation. We jumped around from Houdini to Rhino to Maya to Blender to Zbrush to Photoshop to Mudbox to Cinema4D to QGIS to SketchUp to AirLink to OculusLink to SteamVR. We were struck by the digital skills required to achieve, build or make even one tiny piece of our world and the constant need to use a specific piece of software.

Cost = the sky’s the limit

or rather the universe but a conservative estimate, $7,000.

Page 4 VR Stories