Home 1. Introduction 2. Markers 3. Archive 4. Audible Markers 5. Visible Markers 6. Notational Markers 7. Conclusion

6.1. On Ballet mécanique 6.2. The Rests 6.3. Performing with Ballet Zürich 6.4. Markers

The placement of the rests in the original composition (and in our arrangement) is impressive. During long minutes of crashing fortississimo, Antheil builds up the tension for the massive silences by placing a series of irregular silences into the music, though never exceeding three eighth notes. The music is incessant, overpowering, and overwhelmingly loud. From bar 1138 on, he begins stopping and starting the noise by inserting gradually longer chunks of rests. A few seconds later, in bar 1221, there is the most arresting silence hitherto composed: 64 eighth-note rests in a row, for a total of eighteen seconds of silence.1 This comes during the finale of possibly the loudest piece of composed classical music.

EXPLANATORY VIDEO

an introduction to the silences of Ballet mécanique

footage drawn from a performance of The Ballet Mecanique Robotic Orchestra at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, March 2006; programming and editing by Paul D. Lehrman; robotics by the League of Electronic Musical Urban Robots (LEMUR); Eric Singer, director

Antheil’s silence provocation has remained largely unnoticed by musicians, except for Maurice Peress’s guide to conducting American music:

[…] an elaborate sacrifice is dramatized in the closing moments of the piece when, after a fiendish cadenza, the Pianola—the machine—breaks down. Antheil may very well have borrowed this notion from his Third Piano Sonata, Death of Machines (1923). The Pianola stutters and becomes stuck on a single phrase repeated over and over again: a trill and leaping clusters, followed by a moment of silence. As the “machine” winds down, the phrase is stretched out even more, and Antheil introduces increasingly longer silences. According to Slonimsky, this is the first time in the history of western music that silence is used as an integral part of a musical composition. […] To my relief, our audience got the idea and did not interrupt the twenty‐second‐long silence with applause.2 (Peress, 2004, p. 124)

Antheil’s explanation of his intentions came in a letter to poet Ezra Pound:

Here I stopped. Here was the dead line, the brink of the precipice. Here at the end of this composition where in long stretches no single sound occurs and time itself acts as music; here was the ultimate fulfillment of my poetry; here I had time moving without touching it. (Antheil, in Whitesitt, 1989, p. 105)

The hammering intensity of Antheil’s approach to silence comes through in this quotation about Igor Stravinsky, on whom Antheil had modeled his musical style. As with Stravinsky, silence for Antheil was certainly not a passive waiting:

The silences of rests took on a fierce intensity—I could see the beats hammering away in his brain as he breathed in anger—so unlike the passive waiting or the common injudicious trimming of the supposed non-music of rests. (Smit, 1971, p. 9)

On page 129, almost at the end of the piece, comes an extremely long, empty bar containing 64 eighth notes of silence, perhaps the most dramatically printed page of silence ever.

Figure 1: pages from the Ballet mécanique score showing increasingly long silences (Schirmer: 2000)

Musicologist Julia Schmidt-Pirro describes the effect of these long silences:

[…] the music accelerates seemingly beyond control. Following this near-chaotic passage, a musical turning point is suddenly reached: an unusually long passage of silence. […] Coming right after the preceding masses of sounds, this sudden silence acts as a space where previous notes seem to echo. (Schmidt-Pirro, 2006, p. 412)

That echoing effect, like the residue of noise that one hears after a loud rock concert or the silence when one struggles into the house during a windstorm, is the startling experience of these silences.

Audio: excerpt from Ballet mécanique (Gil Rose conducting the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, BMOP: 2016)

Pirro continues:

One might argue that, in employing these passages of silence, Antheil does not so much interrupt sound with silence as invoke sound through its absence. (Schmidt-Pirro, 2006, p. 412)

I like Schmidt-Pirro’s concept of evoking sound through its absence, similar to examples from Pärt and even Chopin. But my own interpretation is slightly different: Antheil saw silence as a means of emphasizing the radical timescale of Ballet mécanique. The silences have a functional quality of interruption, making the noises before and after seem louder. But they serve more than that: the silences get longer and longer, becoming structural elements in their own right. The machine stops and starts, stops and starts, showing that Antheil is in control and that the machine obeys his will. The markers for these silences are the machinery arrayed over the stage: electric bells, a siren, two airplane propellers, and sixteen player pianos.3 During the long silences, the non-playing of these dramatic instruments marks noisy silence in the same way that the metal band Dead Territory embodies it in their interpretation of Cage’s 4’33”: by evoking an intensely dramatic and fraught situation that would in normal circumstances call forth a wall of sound.

The prescribed tempo in Ballet mécanique is so rapid that the performers cannot realistically count eighth notes in real-time. Yet Antheil deliberately chose to notate the silences in tiny slices of time as long sequences of eighth-note rests. His score depicts something the audience and performers are experiencing: overwhelming silence and speed, the “death of machines,” a sort of comic desperation that would be seen a decade later in Charlie Chaplin’s film Modern Times (1936).

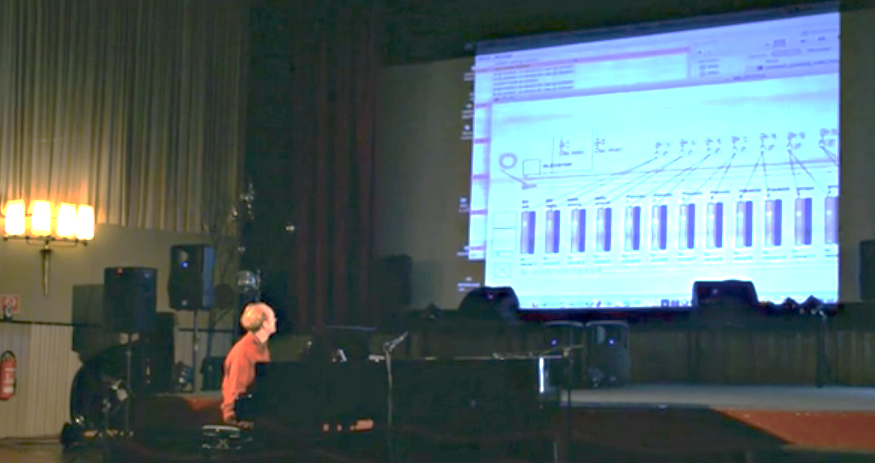

Figure 2: balancing the first eight-channel installation of Ballet mécanique with midi expert Paul Lehrman and composer Oliver Schneller at the SinusTon Festival in Magdeburg (author’s photo, 2013)

Antheil was using sounds and silence as structural components, as building blocks in his “time-space continuum” (Oja, 2001, p. 84). Antheil’s time-space continuum, inspired by the Cubists and Ezra Pound, suggested that art made from blocks could exist in simultaneity to itself. Time and space could be conflated and confused through bold juxtapositions of elements. Ballet mécanique represents Antheil’s most successful attempt to illustrate his theory.

Figure 3: This photo is from the première performance with Ballet Zürich, January 20, 2024, of my arrangement of Ballet mécanique for solo piano and 64-channel sound system, with sound design by Paul Lehrman, choreography by Meryl Tankard, and projections by Régis Lansac (Zürich Opernhaus, 2024).

Did Antheil regret placing these extended and chronometrically precise voids amid the insanity of the Ballet mécanique and its airplane propellers, sirens, and alarm bells? This suggestion is supported by Antheil’s revision of the score thirty years later, in which he removed all the silences. He was resentful of his artwork’s scornful reception at Carnegie Hall in 1927 and felt it had ruined his career. But he was wrong to silence himself. I believe that the original silences were radically brilliant. The careful and methodical buildup of longer and longer rests is deliberate and compelling, a clear compositional strategy. Perhaps buildup is the wrong word, however. Each rest comes as a total surprise—the pauses are in no way prepared by the music. This represents a conceptual difference with the silences in Beethoven’s opus 111, which are prepared by his notes (see Chapter 5). Antheil’s music just abruptly stops, and then it continues. If there is an emotion, it is one of astonishment.

There is also a rather fundamental difference between Antheil’s and Cage’s approach to silence. Here, Cage reflects on materiality in reference to silence:

Now what about material: is it interesting? It is and it isn’t. But one thing is certain. If one is making something which is to be nothing, the one making must love and be patient with the material he chooses. Otherwise, he calls attention to the material, which is precisely something, whereas it was nothing that was being made; or he calls attention to himself, whereas nothing is anonymous. (Cage, 1961, p. 114)

This is the opposite of what Antheil is doing: he is neither loving nor patient. More specifically, his use of eighth-note rests emphatically calls attention to this nothing. Antheil’s nothing is not anonymous, which is why I found it such a revelation. This is silence as materiality, silence as a thing, silence as noise. I am encouraged in this assumption by Antheil’s letters (Whitesitt, 1989, p. 105), by Ezra Pound’s analyses of Antheil’s music, and most of all by the actual manuscript, written in Antheil’s hand.

Figure 4: photocopy of Antheil’s manuscript (1923/24) showing the full bar of 32 eighth-note rests on page 343 (New York Public Library for the Performing Arts)

The piano parts are notated differently than the percussion or other instrumental parts. The piano parts were intended to be mechanical pianos—hence the eighth note rests could be reminiscent of the punched holes in pianola rolls. I like this confluence of technology and graphic representation. A modern pianist performing this score does not need the restlessness of that representation. But the score contains its roots in the mechanisms that Antheil imagined, made tangible in an ever-turning piano roll.

Even if they do not see the notated score and do not know the history of the pianos, the audience feels the flowing urgency of these silences. The preceding rapid succession of eighth-note notes in Antheil’s music might lead the audience to perceive the silences as fast and agitated too, echoing the mechanical nature of the pianolas, which constantly advance with relentless, regular motion. This perception of an audible “shadow” or “afterimage” could imbue the silences with a sense of speed and urgency, as though they are being propelled forward—metaphorically by Antheil’s “time flowing through it,” and literally by the momentum of the composition’s machinery. This perception may come from the presence of a constant fast pulse in sound that extends or continues (like an echo) when the sound abruptly stops.

The pianolas suggest an unperturbed, flattened approach to metered time that does not distinguish between strong and weak beats. Antheil chose a meter of 8/8 (in place of 4/4) or more extremely 64/8 (in place of 32/4). By choosing a meter measured in eighth notes, he was ensuring that there would be neither strong nor weak beats.

Figure 5: The inside of a pianola reveals the paper roll, the mechanism, and the air tubes that connect to the piano hammers. Unpunched paper equals silence. The holes in the paper equal specific piano notes. In this photograph, the paper is wound to the end, so no holes are yet visible. This picture is thus of the silence preceding the music. (Mechanical Music Museum, Northleach, U.K.)

Antheil could have (and indeed maybe should have) notated the empty pianola measures with a number of beats (quarter notes were the standard), a duration in seconds, or simply a time signature. His choice to notate excessive numbers of eighth-note rests is either pointless micromanagement or it is a way of communicating something important about the nature of the silence. Although a pianola does not play silence, perhaps the rows of eighth-note rests represent the continuous rotation of the paper roll. The eighths could then be seen as the quantification of time, linked to machinery and industrialization, again heralding the spirit of Charlie Chaplin’s films.4

Antheil wrote the eighth notes in the automated pianola staff on his score. He notated nothing (not even staves) in the manuscript for the live performers during this cascade of silences. This reinforces the idea of mechanical, inexorable, chopped-up silences: these are the silences of the machine. A 64/8 bar for Antheil makes a statement about sixty-four eighth-note divisions of time, which is not 32 quarter notes, nor 16 half notes. Also, the manner in which he notates the rests by hand, in a messy and confused script, recalls the hectic rush visible in Beethoven’s manuscript of opus 111. Antheil was in a hurry but still took the trouble to write out the detailed rests physically.

Antheil is playing with the audience’s expectations. The silences unfold in a fast tempo and are often prefaced with extra loud sounds (electric bells). After a few bells and sirens, the audience wonders if they are markers for the silences. But they are not. There is no consistency in the pattern that enables prediction. Silence comes abruptly, at unexpected moments. The effect is that the audience becomes paralyzed with a kind of fear at the sudden, awful silence; their ears run out of breath.

Onstage as a performer, the tempo feels incredible, inevitable, awesome. By the time I arrive at the silences, the action up until then has been so wild and relentless that I am shaking. I fear that my breathing is louder than the silence and that my body will collapse under the pressure. What excites me as a pianist is that Ballet mécanique treats silence not as a gap nor an absence but rather as a thick, heavy, powerful substance. The deafening quality of the silence arises because the preceding cacophony sets up an intense auditory expectation that when abruptly met with silence, leaves a resonant void. This amplified silence feels as loud and as materially present as the preceding rush of sound. The highly mechanized experience of this composition gives it an impersonal aggression in which the silence is as palpable, as “thingy” (Voegelin’s term) as the noise.

In some audience members, it may evoke fear or astonishment, but it could also recall and emphasize the loudness and obsessive ostinato rhythms, making present the machines and instruments on stage. By incorporating silence as an element of the music, Antheil emphasizes the mechanical nature of the piece, highlighting the start-stop action of machines.5

After I had written it, I felt that now, finally, I had said everything I had to say in this strange, cold, dreamlike, ultraviolet-light medium. (Antheil, 1945, p. 137)

The effect is to make the resumption of sound more striking and to give the composition a disjointed, almost cinematic pacing, akin to the editing of a film. Each strange, cold, ultraviolet onslaught of silence is followed by an onslaught of sound. The silence contains no affect, no emotion, no meaning. It is not multidimensional, to use Margulis’s term. Antheil refers to the silence of interplanetary space, and the heat of an electric furnace, but these are not rhetorical notes nor silences in the sense of serving a narrative function within the music. The silences deliberately exist outside and separate from the music around them. If any emotion is communicated, then it is astonishment, surprise, or a sensation of overwhelming intensity. And that surprise-separation affect suggests control and power, reinforced by the mechanization of the instruments that frame the silences. In Antheil’s futurist 1920s world, silence becomes its own kind of thundering, a time moving without us touching it.