Home 1. Introduction 2. Markers 3. Archive 4. Audible Markers 5. Visible Markers 6. Notational Markers 7. Conclusion

2.1. Introduction 2.2. Markers 2.3. Framing 2.4 Eloquence 2.5. Dimensions

2.2 Potential Markers for Silence

Silences can be signaled or sometimes imposed through markers which may include icons, gestures, flags, text, signs, pictograms, architecture, audience behavior, ritual, spiritual ceremony, the word “shhhh,” bells, alarms, and, at the very worst, physical restraint and murder. Here are some common examples:

-

A marker that imposes silence: Prior to an orchestral concert, the conductor ritually indicates silence to the audience and the musicians by tapping three times with the baton. Most people in the concert hall recognize and respect this signal, which leads to anticipatory silence in the audience and orchestra. The signal is both audible (the three clicks of the baton) and visible (the conductor is seen making the gesture).

-

A marker which summons silence: The absence of sound can itself be a marker for silence, as in a 19th-century library lined with books. The clichéd furniture (oversized leather chairs, green porcelain lamp shades, oak tables) provide visual cues to be silent, assuming we are familiar with this language. And the audible hush pervading the room perpetrates a continuing cycle of quiet, again based on ritualized cues of behavior. The presence of sound, as in audible markers like bells, gongs, and wind chimes can also summon silence.

-

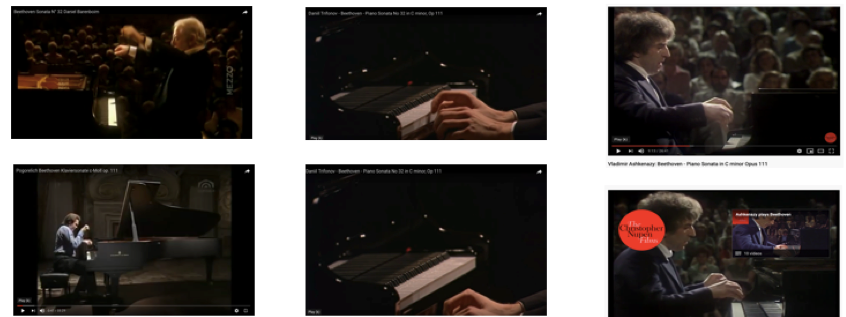

A marker that describes silence: A pianist performing a Beethoven sonata throws her arms dramatically behind her during a rest, gaining extra audience attention for her silence. Her gesture, which serves no audible or technical purpose, communicates the silence theatrically to the audience despite the sound still reverberating through the hall. When Katie Mahan does this, her moving arms become gestural markers for eloquent silence.

Figure 1: Katie Mahan performing the 4th-bar rest of Ludwig van Beethoven’s opus 111 piano sonata (YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sk8oL4jDWIw)

Silence is ephemeral and is slippery as a word, as a concept, and as a phenomenon. Philosopher Georges Bataille characterizes silence as a “slipping” word because it is “the abolition of the sound which the word is; among all words, it is the most perverse, or the most poetic: it is the token of its own death” (Bataille, 1978, p. 16). By speaking of silence, by trying to take its measure, we disturb it and we break it.

Perhaps my model of markers offers a solution to Bataille’s paradox. By marking the phenomenon of silence, the musician captions it, wordlessly. Visual markers especially may sometimes allow the silence to (less slippingly) communicate, maybe without breaking it.

Sometimes the marker for silence includes the person gesturing (a conductor signals for silence, and is then silent), and sometimes it does not (a preacher holds up a hand, palm facing out to the audience, signaling silence for the congregation, even though he/she continues to speak). Sometimes, silence is imposed through a silent gesture (finger to lips), sometimes through a noisy gesture (clapping twice loudly in front of a rowdy classroom). In many spiritual practices, bells indicate subtle changes in activity—activities that take place in stillness, simultaneous to the non-stillness of the bells.

How the markers are sensed is important: It is tempting to sort the sensoriality of markers into audible and visible. Yet cues for silence can be highly subtle and may involve multiple sensory inputs: smells, rituals, lighting, or memory. For example, the smell of a spice or a flower could recall the past and cause one to become suddenly still. The dimming of lights in a theater produces a hush in the audience, a keen sense of anticipation and also a tiny rustle as everyone settles into their seats before the show. Thus, markers can indeed be visible or audible, but they can also be multi-sensory, feeding back on each other, reinforcing or diffusing the silence around a performance.

From a musician’s perspective, markers are the signals that are used to communicate silence to the audience.

Here is a possible definition from the perspective of the performer.

Silence markers = signals that are used to shift attention and thus:

-

impose silence,

-

summon silence,

-

shape the perception of silence.

And here is a possible definition from the perspective of the listener.

Silence markers = signals that draw attention and thus:

-

impose if and when one must keep silent,

-

are the symbols by which we understand cognitively that silence is happening or being summoned,

-

shape the personal narratives of the listening experience.

The distinction between imposition and shaping is an important one insofar as it affects the relationship between listener and performer. A conductor pointing the baton straight out between movements may be imposing silence on the audience and musicians. But, during the performance, the baton may be used horizontally to shape how the listener experiences silence. Both of these gestures employ the baton as a marker, but the effect is very different. Markers are the caption that gives performed silence its meaning. They will be the tools used to examine performed silences in the subsequent chapters. There can be some overlap between types of markers, as a given marker might, for example, contain both visible and audible aspects.

Visible Markers

Visible markers for silence are a very prominent focus of this research. The visual aspects of performed silence can be indicated through various means and include performative embodiments of silence. Specifically, performed embodiments encompass body language, gestures, hair tossing, and facial expressions. For example, in theater, a performer can convey silence through their posture, facial expression, or movement. In dance, silence can be represented through stillness, pauses, or specific gestures. In painting, silence can be suggested through an absence of sound or color (Rothko) or pigment, as well as more literally via a scene that evokes silence (Hopper).1 But visual markers also include lighting, signs, and symbols which can be expressed through theatrical or architectural means.

Figure 2: These are paintings by two artists who engaged extensively with silence: Untitled (Black Blue Painting) by Mark Rothko (1968) (https://www.phillips.com/detail/mark-rothko/UK010121/15) and Room in New York by Edward Hopper (1932) (https://www.edwardhopper.net/room-in-new-york.jsp).

Visible markers for performed silence cover a wide variety of signals and cues. Here is a partial list from this research project of some of the embodied (gestural) visible markers that are documented in the archive and the case studies: aggressive gestures, balletic gestures, poised gestures, contorted face, curving arm gestures which seem to summon or prepare nostalgic silences, Dadaist embodiments, dramatic gestures in romantic pianistic style, extravagant movements, fingers hovering in a precise embodiment above the keys, hairstyle, hair-tossing, hands, head thrown back, immobility, magisterial posture, motionless posture, moving without playing, poise, posing, swooping arms, tuxedo…

Non-performed Visible Markers

Visible markers do not always originate from the performer. There are many non-performed but visible cues for silence. One example is lighting cues. When the lights dim in an opera house, it often induces a hush in the audience. The dimming acts as a marker for attentive silence, a cue that the show is about to begin (or has begun already). Some composers use this as a technique for observing silence. An example is Straal by Argentinian composer Cecilia Arditto, in which the pianist responds to a flashing screen. Another example is a jazzy improvisation by Australian composer Matthew Schlomowitz, in which the musicians react to the on-and-off states of colored light.

In these examples of light, gesture, and image, silence correlates with light or darkness, making sound and/or silence visible and creating a binary experience. Here is a partial list from this research project of some of the external visible markers that are documented in the archive and the case studies, including spatial and ritual markers: architecture, darkness, empty glass, hall (design, curtains, organization), handcuffs, page-turns, blank paper, rocks (nature), stage lighting, Steinway & Sons (instrument), table, water (nature)…

Gestural Markers

Gestural markers for silence can include the movements of a pianist freezing in mid-air to indicate silence and hold the audience’s attention; the gesture of the drummer poised to strike their drum, raised sticks above their head; the attitude of the guitarist with eyes closed; the pose of the DJ with head bowed, the pianist vigorously nodding their head to an unheard beat. Or the many gestures that conductors employ for silence, whether compelling their musicians or their audience to be still. Or a hand raised in the air by a politician. Or a monk’s crossed arms inside his cloak. The eloquent silence examples proposed in my Noisy Archive (Chapter 3) will often demonstrate the different dimensions of performed silence that are communicated within the embodied performance of silences.

Academic research on musical gesture generally corroborates my suggestion that a performer’s embodiments can significantly influence silence perception. In “Visual Perception of Expressiveness in Musicians’ Body Movements,” Sofia Dahl and Anders Friberg write:

Musicians also move their bodies in a way that is not directly related to the production of tones. Head shakes or body sway are examples of movements that, although not actually producing sound, still can serve a communicative purpose of their own. […] We prefer to think of these performer movements as a body language since […] they serve several important functions in music performance. (Dahl & Freiberg, 2007, p. 433)

Musical gesture is often considered to be a multimodal phenomenon. It is not only about the visible but also about the auditory and the kinesthetic. In their article for the journal Music Perception, “All Eyes on Me,” Küssner et al. show that a musician “acting” as a soloist not only exhibits more pronounced body movements but also attracts greater visual attention from observers, irrespective of their actual musical role. Switching the roles so that the accompanist acts as a soloist results in greater attention being paid to the person who embodies the role of the soloist. “Gesturing and movement are highly likely to attract overt visual attention, possibly taking precedence over auditory cues” (Küssner & Van Dyck, 2020, p. 198). An example would be Katie Mahan’s performance of Beethoven’s opus 111, in which she exhibits highly pronounced body movements. Her performative body is “acting” as a soloist.

Musicologist Nicholas Cook gives an example of this phenomenon, describing a striking public display of gesture:

In a 2002 concert performance […] Russian pianist Grigory Sokolov performs virtuosity as much as he performs Chopin: his hands often fly up after a particularly telling note, providing an idiosyncratic balletic correlate to the sound. His performance makes perfect sense on CD, but seeing it adds further meaning. The striking quality of public display in his playing is redolent of the cavernous spaces of modern concert halls and the star quality of the international virtuoso. He enacts exceptionality. (Cook, 2008, p. 1187)

Enacting exceptionality or performing the role of a soloist might have a self-fulfilling effect. But expressive gestures are not only about enacting exceptionality or performing as a soloist:

The musical gesture manifests itself as musical meaning at the intersection of sound, motor movement (whether open or suppressed), stylization and figuration. It can be associated with the visible or audible motor movements of the music-making body; it can refer to a typical sound progression or even to a culturally styled gestural convention. (Craenen, 2014, p. 166)

Pianist William Marx effortlessly embodies a combination of these manifestations in his performance of 4’33”. He mixes classical performing conventions (tuxedo, massive grand piano) and a suggestion of visible motor movements (highly formalized and emblematic gestures) of the music-making body. His deliberate non-playing during the performance is made more effective by this stylized intersection.

Gestures can have many communicative embodiments and can arise from performance techniques. But communicative embodiments can also arise independently of functional gestures. Musicians are able to perform complex functional and expressive gestures simultaneously and independently:

Redundancy (or variability) in the motor system is therefore a crucial condition to perform tasks well and could explain why musicians performing unusual(ly) expressive gestures are still able to achieve a certain musical goal (i.e., produce an adequately expressive sound). (Küssner & Van Dyck, 2020, p. 196)

Research on musical gesture offers little consensus on functional taxonomies, underscoring their multifaceted and complex role in performances, as well as the difficulty of categorizing movements unequivocally; alternative terminologies are used. Some research fields, particularly those associated with body movements, such as kinesiology and biomechanics, avoid the specific term “gesture.” Within music performance research, gestures can describe motion or movement (Davidson, 1993; Gabrielsson & Juslin, 2003), expressive movement (Pierce and Pierce, 1989; Davidson, 1994), or corporeal articulations (Leman, 2007). Performance scholar Carrie Noland describes gestures as learned techniques of the body or corporeal forms of cultural communication (Noland, 2009). Music theorist Robert S. Hatten suggests that a gesture is “any energetic shaping through time that may be interpreted as significant” (Hatten, 2006, p. 1). If that energetic movement lacks meaning, then Hatten refers to gesturing instead of gesture.

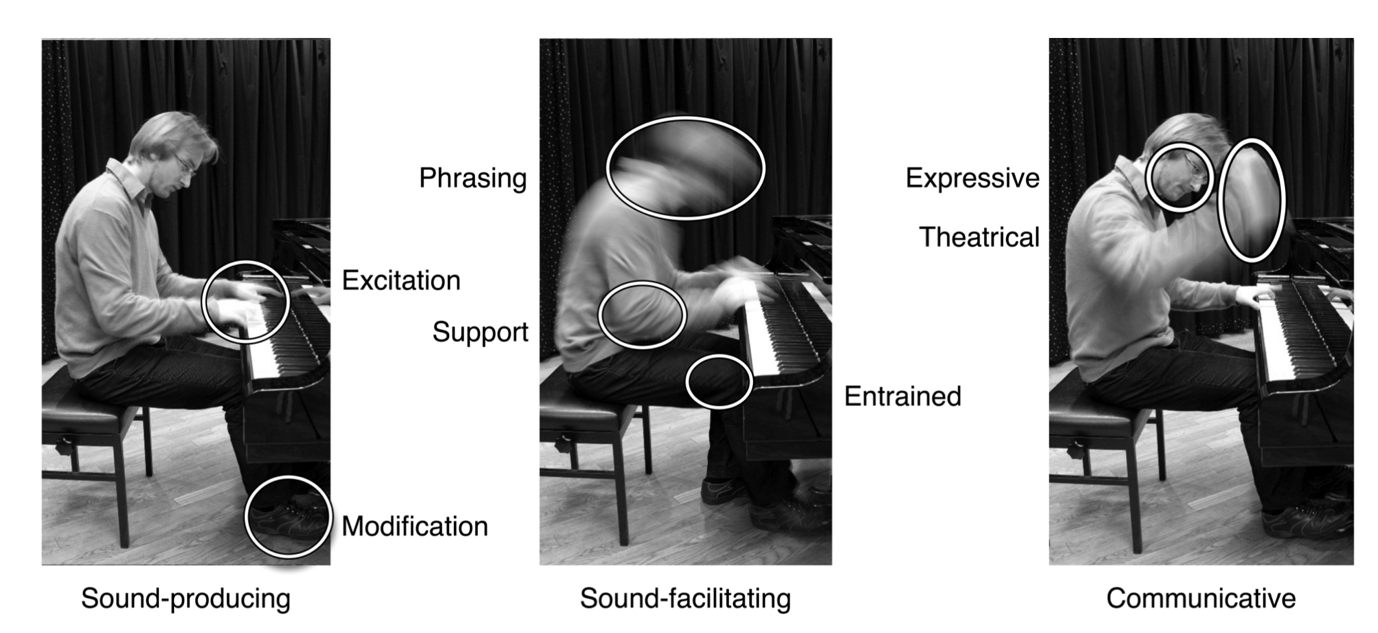

An approach that is more closely aligned with my research assigns labels of sound-producing, communicative, sound-facilitating, and sound-accompanying gestures that include elements of visual communication and interaction (Jensenius & Wanderley, 2010). Jensenius’s communicative gestures correspond to my eloquent gestures.

Figure 4: schema identifying gestural zones of the pianist’s body (Jensenius & Wanderley, 2010, p. 9)

For the purposes of this study, the term “gesture” encompasses any movement made by the performer in relation to the instrument. However, it is crucial to differentiate that not all movements serve as significant markers within the performance context. For instance, a physical exertion such as a leap may not equate to a gesture imbued with eloquence. A performed silence is not necessarily an eloquent silence. I concentrate specifically on those gestures that imbue the surrounding silence with eloquence: gestures that are (intentionally) executed to enhance the audience’s experience of silence. These gestures straddle the line between technical necessity (such as navigating the keyboard) and expressive eloquence (using dramatic movement to convey emotion to the audience), underscoring the multifaceted nature of performer intent and the nuanced interplay between action and silence.

Figure 5: Classical pianists interpreting the fourth bar rest in the first movement of Beethoven’s opus 111: As will be discussed in Chapter 5, pianists perform the silences in Beethoven’s sonatas with an amazingly complex and varied vocabulary of gestures, confirming the difficulty of categorizing silence embodiments.

My analyses are influenced by my method of “reflective imitation,” which is a re-performing or re-enacting of other performers’ gestures. I analyze their gestures and embodiment to try to pinpoint the motivations of the performer and then re-use those motivations in my own performance to engender similar effects. I use video extensively as both a technique and an output. While my interest is primarily the silence gestures, I am inevitably drawn into the performance complexities of the notes as well.

A similar process of copying and re-rehearsing (Schechner) is also being tested currently by the artistic research group of violinist Barbara Lüneburg at the Anton Bruckner University in Linz. Her “Re-enacting Embodiment” method is similar to my approach and involves intensive back-and-forth work with performance videos in an attempt to shed one’s own performative habits and trade them for another’s: “The process of musically and physically re-enacting another person’s interpretation provides in-depth insights into the intertwining of musical interpretation and embodiment” (Lüneburg, 2023, p. 26). Similar to Lüneburg, my research focuses on bodily repertoire, body language, and the discovery of potentially new performative results.

Audible Markers

An electric bell ringing outside the auditorium becomes an audible marker summoning silence. So is a Tibetan gong calling monks to meditation; a massive bronze bell ringing high above a city is a call to mourning; or The Last Post played by a trumpet to commemorate the dead. These sounds call for and evoke silence.

Audible markers can be noisy and can have a role in implying silence despite their noisiness. The tolling bell in the distance can suggest silence to the listener or even summon silence in a crowd.2 The bell acts noisily as a marker, implying or imposing silence on the group of listeners. One musical example is American composer Alan Frederick Shockley’s Cold Springs Branch, 10pm for piano, which includes a low Eb representing a tolling bell. The composer does not tell his audience what the bell tolls for, but it evokes an experience of silence.

In Hollywood movies, audible markers for silence are common, for example, the banging of a wooden shutter in a western ghost town or the whipping noise of a flag waving above an empty schoolhouse. These sounds cognitively inform the receiver that silence is happening. In nature, weather and animal sounds can also serve as markers and cues for what seems to be silence. These might include birdsong, waves, rustling leaves, a gentle wind, crickets3 or frogs at night, and cicadas. These audible markers indicate a context in which listeners feel silence to be present, whether it is or not.

Audible markers can be loud or soft, subtle or overt, silent or heard, notated or not. Here is a non-exclusive list showing the variety of audible markers that occur in this research: amplification (on or off), audience rustle or applause, audience awe, audience censure, breathing, clock ticking, explanatory text, humming, loudness, meta-silence, silence as a behavioral construct exterior to the artwork, metronome, noise, notes, performer’s silence before the concert, stopwatch sounds, tradition, traffic, voiceover, warmup riff, yelling audience, wrong notes…

Symbolic Markers

There are many symbols that call for silence and have temporal permanence (they do not change over time), like rests in a musical score or a sign indicating “quiet please” outside a recording studio. These referent markers are printed, written, or drawn and have the benefit of making no sound themselves. They can last a long time. This 8th-century icon communicates its message as easily to the modern viewer as it did 1200 years ago. These symbols for silence will be referred to as “symbolic” markers.

When percussionist Max Neuhaus created a silent walk, he stamped “LISTEN” on the hands of each audience member. The inked letters were markers that invited the audience explicitly to use their ears but implicitly to be silent while doing so. Symbolic markers are instructive. They command or impose silence on the audience/listener.

There are other situations in which a symbolic marker may be unseen by the receiver. Rests printed in the score cannot be seen by the audience. They are meant to be interpreted by the performer and are only transmitted indirectly to the receiver.

Outside of performance situations, many of these symbols are in daily use and are immediately recognizable.

Spatial Markers

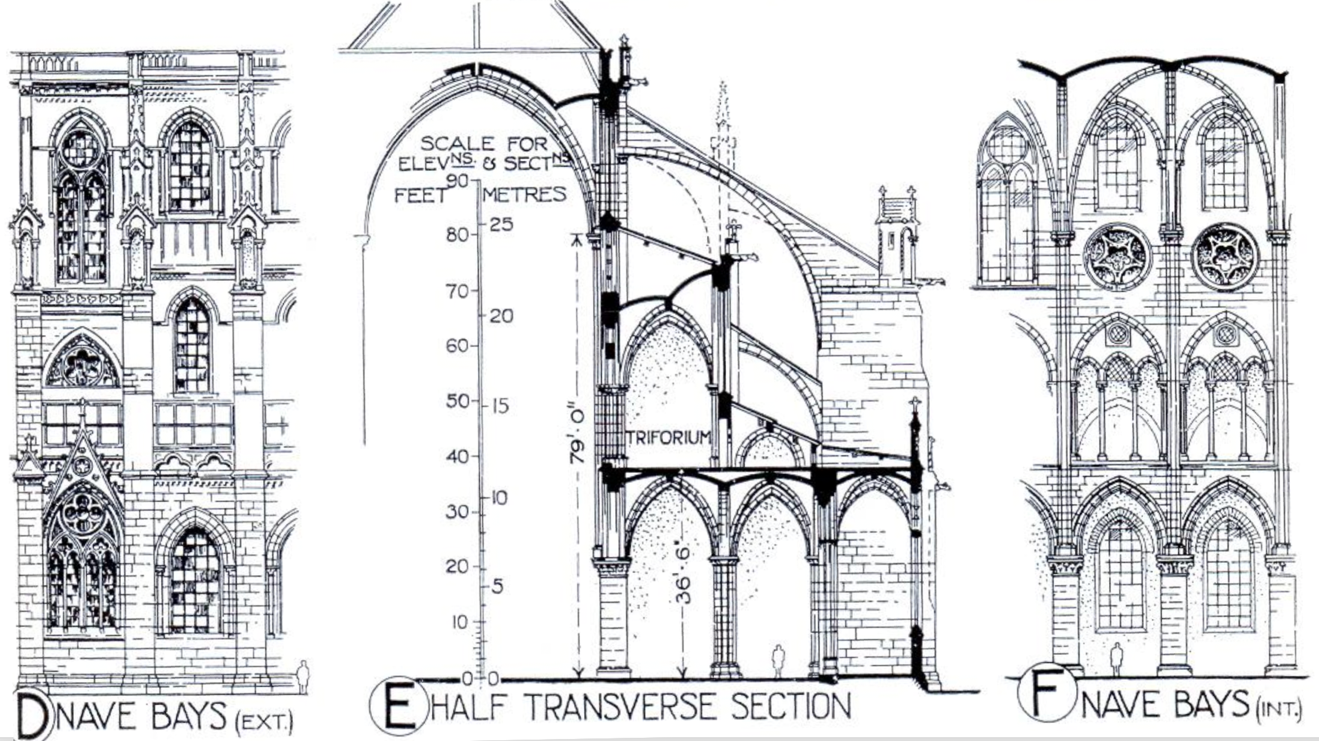

Spatial markers are usually visible and constitute a large vocabulary within built design: walls, curtains, the arches of a medieval cloister, tinted glass, a reflecting pool, and ivy-covered walls. These can all suggest a sense of silence to the people using the space. For example, in a theater, the markers for silence might be held within the frames and cues of curtains and lighting. These markers might be intangible (as in lighting) or tangible (as in walls or curtains). Sometimes, the effect of spatial markers may not be directly visible: for example, in the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, many vaults and balconies above the congregation are unseen, yet they serve as resonating chambers that create a unique acoustic.

This acoustic is often called into service in the experience of silence. For example, at the end of Bruckner’s Te Deum, the audience sits still, in awed and silent admiration of the echoing last chords. The combination of stone, resonant spaces, and curved vaulting create a long and unique diminuendo of sound after the last chord has been played by the musicians. There are abundant examples of architecture influencing the experience of silence—whether in a cathedral, classical concert hall, chamber music hall, living room, airport, elevator, shopping mall, restaurant, or bar. In each, the sound of silence is different. Effects of ambiance, room tone, acoustic, and reverberation color the listener’s silence experience.4 Cobussen echoes this:

Hearing several sounds simultaneously produces a complex materiality, the measure of which is not strictly additive. And while we know that sounds often leak from place to place, it is all too often assumed that rooms are bounded and neutral physical spaces. Yet, spaces actively shape the sounds that reverberate within them. (Cobussen, 2022, p. 49)

Because spaces actively shape sounds, the listener will experience silences more intensely in a reverberant context: this is ironic because that same reverberation prevents the notes from fading away. Thus, their persistence after the musicians stop is what draws the audience into the experience of silence.

The built environment is an essential component of experiencing musical silence and contributes to the emotional affect of the silence. These silences are situated in space:

Through listening to a place, this place can be perceived not as a fixed context or a preexisting void in which something happens, but as an active and unstable agent, participating and constituted in the moment the action takes place. (Cobussen, 2022, p. 13)

Music and space act upon each other, radiating sounds and silences that interact as unstable agents. This allows the experienced performer to engage with the acoustics during a performance.

Ritual Markers

Ritual, place, and music can encourage non-notated silence to arise. Audience stillness itself can engender silence. In Chapter 1, I suggested the term “meta-silences” to describe these non-notated silences that arise from combinations of music, place (context), and behavior (ritual). These participatory silences are not planned and do not only arise from the music. The audience can also enforce its own silence as a form of social control —"the silence of decorum” (Hodkinson, 2007). It might not be notated or formally planned, but it can often be anticipated. For example, the hush that falls over the audience when the lights dim before a performance is entirely predictable, though nowhere notated.

Multimodal Markers

Markers are not an either/or. They are not always either audible or visible. For example, the shhhh action can be both audible (saying “shhhh”) and visual (look at my finger and be quiet). Further, assuming we have knowledge of the gesture, the shhhh action can be translated purely into an iconic marker: a picture of a person with their fingers to their lips sends the same message as an actual person making that gesture. Another mixed marker is that of putting your fingers in your ears, which can be a call for silence (a gesture for others to react to), as well as self-protection against loudness (I need silence now). More subtle markers can be mixed as well. The children’s book character Paddington Bear was famous for his hard stare, calculated to embarrass someone into shutting up. The stare is a gestural (facial expression) attempt at enforcement, at imposing silence. But it is also a silent marker: Paddington would fall silent while “performing” the stare.

This is an example of a visual marker for silence, which is purely visual. It conveys a high iconic aspect but a low instructive aspect. The VU meter indicates to the receiver that silence is happening at a specific moment, but it does not give an instruction for silence to happen, nor does it communicate any information about the silence. Yet this is a very popular symbol of silence amongst rock musicians, techies, and scientists.

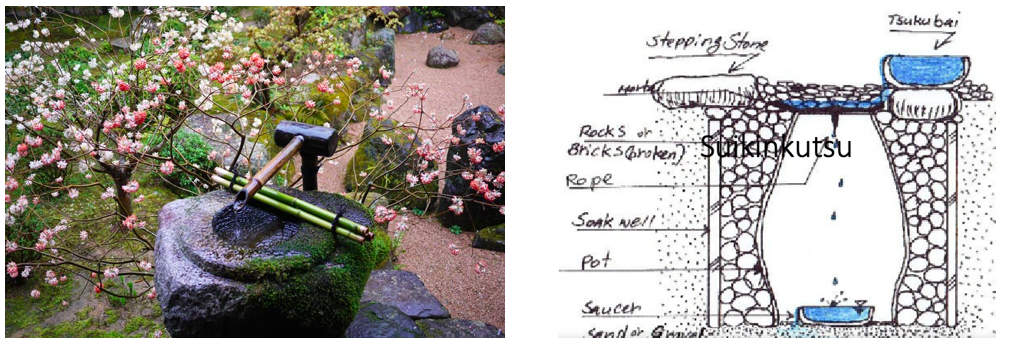

Markers for silence can have their own physicality and permanence and have a temporal quality. Traditional Japanese gardens incorporate the sound of dripping water to convey an atmosphere of silence. The suikinkutsu 水琴窟 (which can be read as “water instrument cave” in the original Chinese) is an upside-down clay pot used frequently in Japanese gardens to create an irregular dripping sound. The effect is remarkably peaceful and effectively communicates an impression of silence, even in gardens that are surrounded by high-decibel modern cities.

Figure 11: A suikinkutsu at Hosen-in Temple, Kyoto (https://traditionalkyoto.com/gardens/suikinkutsu/); the drawing shows the underground structure (https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Creating-a-Virtual-Suikinkutsu-Brewer/8a450662762acefab999ea2204036713b94b3ae2). The large clay pot resonates with the irregular drips of the water. This marker combines audible and visual aspects and exists in a physical/architectural context, as well as a ritual (meta-silence) context. Indeed the picture on the left could be considered iconic in a traditional Japanese setting, as the shape of the object is well-known and highly symbolic. That is, the picture itself evokes a sensation of silence.

Richard Long’s conceptual artwork, A Line Made by Walking (1967), is another multimodal marker for silence. Long created the work by walking back and forth over the same line for many repetitions. The work left traces on the ground he touched.

This conceptual work is an embodiment of silence, a marker for stillness. The line is a marker for what has been.5 The walk is performed quietly over a long period of time, and once the physical embodiment is completed, then the line gradually fades away in silence as the grass grows back, also over a long period of time.

Contextual Markers

A major suggestion of this thesis is that the visual can be essential and unique to our understanding of performed silence. Visual markers allow performers to communicate many dimensions of silence, such as emotion, speed, and accentuation. Does this visual focus mean that eloquent silence loses its eloquence in a radio performance? Not necessarily: radio listeners can easily be transfixed by stillness in a song, breaths in radio plays, awesome pauses in broadcast concerts, and late-night pauses in the shipping news. This appreciation of silence on radio is a common experience, so it cannot be claimed that broadcasting or recording removes the emotional content of silence. Performed radio silence is more than an on/off state, a neutral not-sounding.

So while visible markers are lost between the transmission tower and the kitchen radio, other markers might gain in importance for the listener:

-

These could be metaxical sounds (Amaral, 2022), encompassing the sounds occurring around, during, and within the performance. These sounds, such as room tone, audience rustlings, and incidental page turns, though faint, provide subtle cues about presence which help the listener grasp the context of both sounds and silence.

-

Alternatively, the sounds of breaths, gasps, and the physical efforts of the performer, recorded with sensitive microphones and careful attention, can serve as cues for understanding radio silence.

-

The characteristics of the performance space itself, whether a dry recording studio or a vast concert hall, contribute their unique reverberations to the broadcast, which the listener interprets.

-

The political context surrounding the performance can also become a potent marker for silence.

On the radio, can the audience hear the difference between a performance of Cage’s 4’33” and one of Schulhoff’s in futurum? The short answer is no: they sound the same. But no performance occurs in a vacuum, neither literally nor figuratively. There is always context in performed silences. Chapter 4 will mention a performance of 4’33” on post-Soviet radio in which a strong political context had a powerful influence on the audience experience. This performance of 4’33”, which would have sounded “the same” as a performance of in futurum, nonetheless acquired a totally different meaning due to the atmosphere of state collapse during which it was broadcast. To summarize, even if there is no visual communication, “total radio silence” gains meaning through non-sounding context.

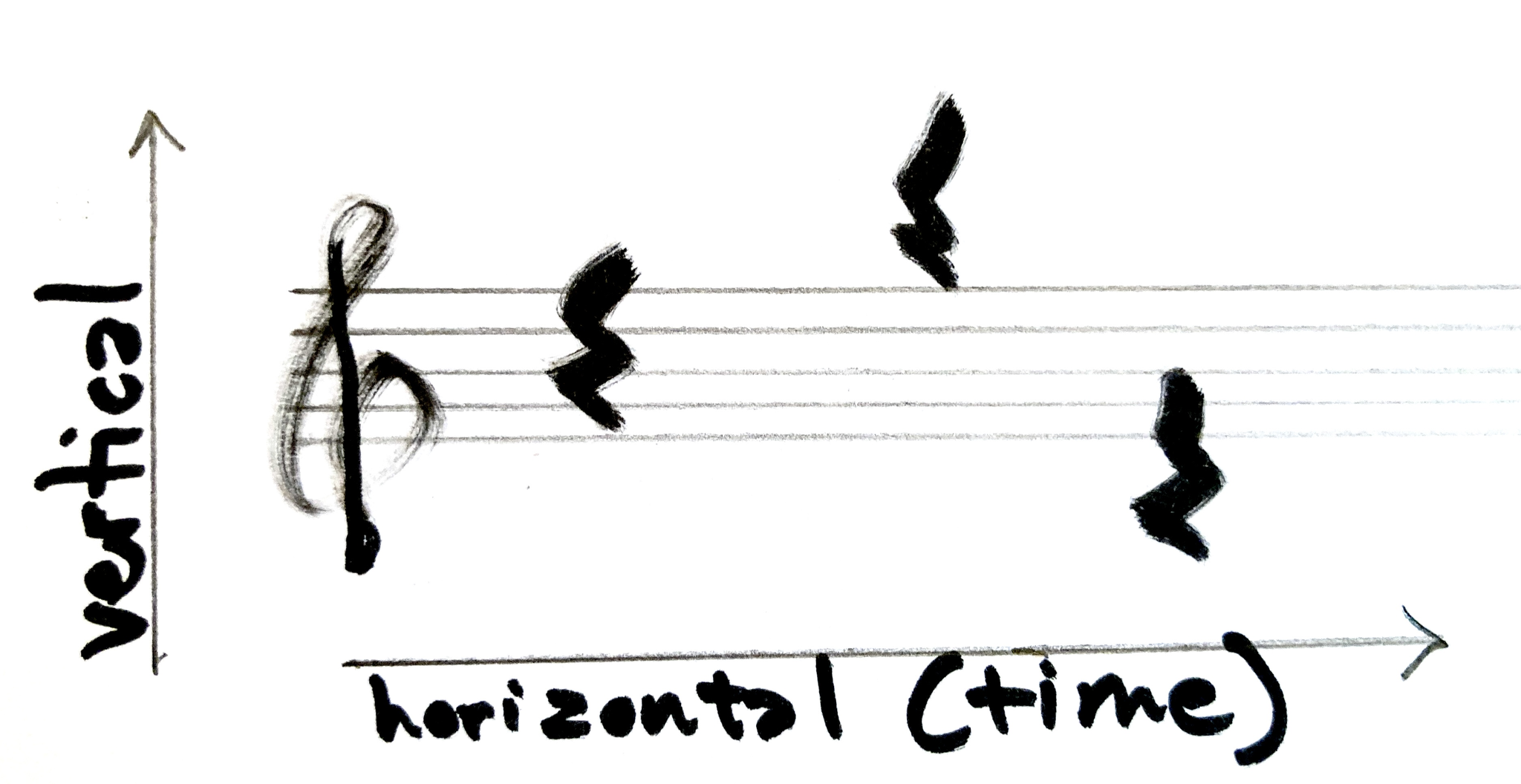

Figure 13: Different vertical placements for rests are acceptable since the vertical axis does not indicate pitch. But in multi-voiced notation, the vertical placement can imply voicing. The horizontal axis represents time. Each rest is placed at the beginning of the time span which it occupies. An exception is made when one rest fills the entire bar: then it is centered.

Notational Markers

Composers in Western Classical and experimental music usually notate silence via symbols in the score that indicate duration. These rest symbols are aligned vertically with the beat at which they begin and are valid horizontally until the end of their notated duration. Although note symbols use the vertical axis to indicate pitch, rest symbols are not pitched. Thus rests are vertically placed wherever most convenient, which can be within or without the stave.

The horizontal axis indicates time so that when the duration of the rest is completed, another rest or note usually follows on the next available beat. During the notated duration, the designated performer, hand or voice does not play notes.

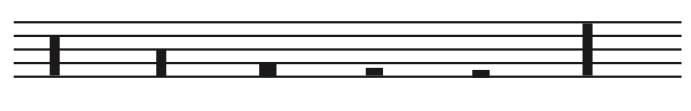

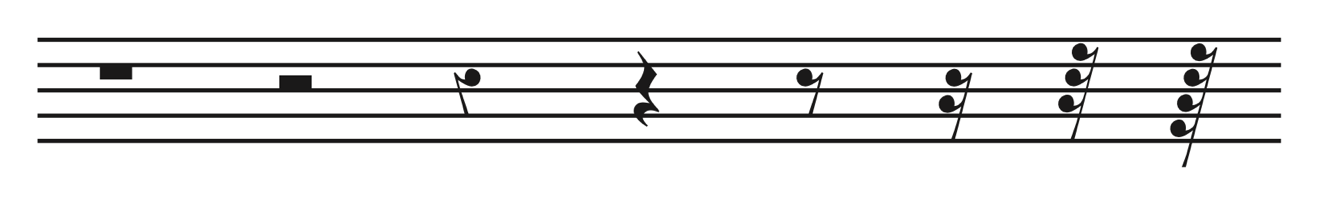

The current western notational system for silence is quite simple, as follows:

Figure 14: An 8/4 bar is measured out into the seven most common symbols for rests. This measure contains 64 thirty-second rests, for example. The different notations on each line add up to the same duration but represent increasingly fast pulsations.

Each individual rest above encodes only one variable: duration. A second variable is pulse or beat, which is encoded in the sequential choice of which rests to use. A rapid pulsation of rests might thus suggest speed, as in the bottom stave. Yet an individual rest (or note) offers no encoding of source, affect, emotion, accentuation, phrasing, direction, symbol, internal, external, mental, physical manifestation, facial expression, or bodily gesture. Why? Do musicians seek neutrality from silence? Must rests communicate nothing about the kinds of silence they imply? Surely the desired silence effects have an importance that is not limited to duration? If so, where is that importance indicated? Where is that knowledge held? This section will answer some of these queries.

At first glance, an enquiring performer might find that standard rests are frustratingly neutral symbols and that no care has gone into their design. But silence notation has evolved through many manifestations since its origins in the late medieval period.

The origins of silence notation are not known. Ancient performed silences may not have been notated at all; or if they were, the notation has not been discovered or deciphered. Greek musical texts mention kenos chronos as a rhythmic silence; or tempora inania as a temporal silence. It is not known if these pauses were ever represented by notational symbols.

In the 4th century, Saint Augustine wrote of silentia voluntaria, referring to pauses outside metrical notation.

Silentia voluntaria is the term for pauses that are not indicated through meter—i.e. pauses that are ‘free’ of the metrical notation—and it might be expected that the ‘voluntary’ nature of these pauses was a mark of something akin to musical expression or phrasing. (Hodkinson, 2007, p. 28)

Again, no visual symbol still exists from Augustine’s epoch, but his text provides two valuable clues. Firstly, that pauses were part of contemporary performance practice, and secondly, that pauses potentially involved a departure from the meter. The role of performed silence in interrupting and thus delineating time is already suggested, even at this historical distance. In Chapter 1, I suggested that silence may both connect and disconnect, like a not/knot. Perhaps Augustine’s silentia voluntaria could be the first suggestion of silence as both not and knot. Little is known about the context or the sound of the pauses he describes. Pauses that are voluntaria, free of the metrical notation, would seem disconnected, “out of time.” Yet their placement within the chant at moments which suggest phrasings implies a connective function.

In psalm singing, silence is a well-attested part of medieval performance practice, but its meaning is not primarily musical. Instead, the focus is on meditation, unity, ceremony, the visitation of the Holy Spirit, and the release of mood-enhancing endorphins through the controlled breathing of the whole monastic community. The transcendent possibilities, or at least the possibility of a change of mental state, are clearly present in the silences of medieval monastic psalm singing. (Hornby, 2017, p. 151)

Musicologist Emma Hornby discusses media distincto pauses in medieval chant, citing a later source:

In the middle of each verse, there was a pause for taking breath, the media distinctio. According to the fourteenth-century Ceremoniae Sublacenses, this pause was long enough for the singers to exhale and inhale again. The media distinctio was considered to be a ceremonial pause, enhancing solemnity of the chanting. It sometimes served as an architectural pause, lasting until the echo of the previous pitch had died away; the length of the pause depended on the acoustics of the building. (Hornby, 2017, p. 143)

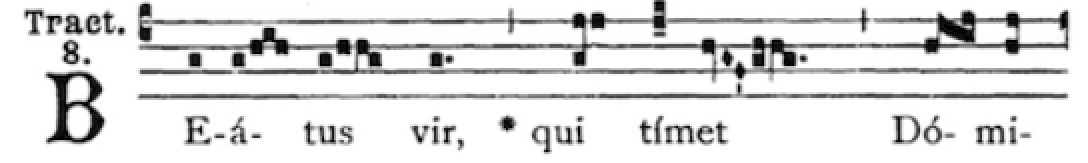

These symbols encode duration as a correlation of height. The longest silence in this example is the finis punctorum, the silence at the end of the composition. Graphically, the symbol stretches from the bottom to the top of the stave. Though somewhat modified in shape and placement, these symbols are still in use. Initially, only long silences were notated; short pauses to breathe might have been simply improvised, staggered amongst the musicians, and known as an implicit part of the performance practice. Somewhere in the medieval era, short pauses began to be notated as thin vertical lines as in this example of Gregorian chant.

Silence notation continued to evolve towards rhythmic precision. By the 17th century, the durations and symbols of rests had been standardized as follows:

Figure 17: semibreve, minim, crotchet, quaver, semiquaver, demisemiquaver, and hemi demisemiquaver, or 64th-note rest (Hodkinson, p. 26)

From a graphic design point of view, the updated symbols are far more whimsical and lighter than their late-medieval ancestors. For example, the quaver almost looks like a breath and suggests speed and lightness. However, the symbols are now encoded such that the taller the rest, the shorter the duration. Hence a hemi demisemiquaver is almost four times as large visually as a quaver, yet it lasts only one eighth as long. This paradoxical system means that very long rests and very short rests are larger and more visually dense, while the most commonly used rests (in the middle of the range) are the smallest and visually lightest.

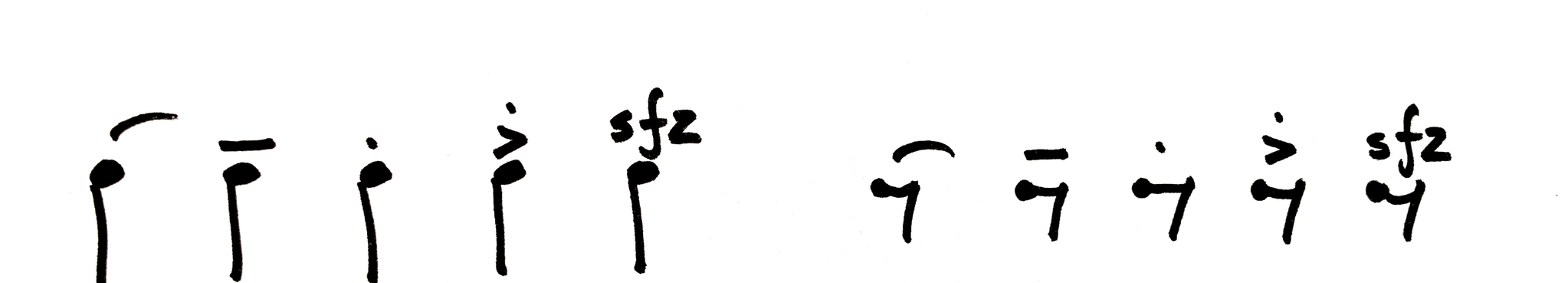

Another critique of silence notation that has been suggested above is that the symbols for silence are neutral, containing only information about duration and possibly beat division. Semiotically speaking, the symbols for silence are no more neutral than the notes themselves, which are also sterile on the page compared to the performed result. However, there is an important difference: notational rules for notes allow a wide variety of modifiers: accents, staccato marks, sustaining lines, phrasing, and so forth:

Unfortunately, there is no notational method for accenting a rest, slurring it, making it louder or softer, sharper or more diffuse. The examples on the right are “incorrect” within the classical notational system.

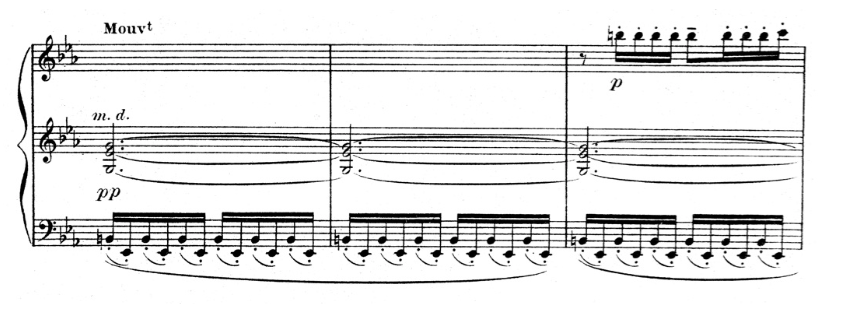

Sometimes performed silences do not originate with a silence symbol (a rest) but rather with a delineative mark. Delineative marks include staccato, portato, lines, accents, and commas. These marks vary in usage between genres, and their interpretation is highly personal for musicians. Interpretive subtlety is necessary: the difference between portato and portamento may be debated in Early Music, but that there is a difference is immediately agreed upon, even though it only impacts the silence by a mere fraction of a beat. Similarly, every singer can identify for themselves the difference between a gasp and a gap, a blank and a breath, whether or not there are established notations for them.

Delineative marks are often placed directly after (commas, breath marks) the note that they modify. Some are placed over the notes whose ending they modify, like staccato or portato markings. The modification (staccato mark, portato mark, line) describes the release of the note.

In this complex example, the staccato marks in the left hand differ from those in the right hand. The combination of staccato points and multiple phrasing arcs is difficult to perform; hence it offers scope for virtuosity of interpretation. The staccato marks in the left hand might have more to do with the attack of the note than the release (an impression suggested by the long and short phrase marks connecting the notes and perhaps inspired by notations for bowed instruments). Yet the staccato marks in the top melody probably affect both attack and release, perhaps creating a series of micro silences between the sixteenth notes.