The Survey and Its Results

There is, in the popular media, a certain tendency to report that actors often “become” the character/role that they are to perform. There are countless stories about actors living their role outside the boundaries of the film shoot or rehearsal/performance space. Debra Winger is reported to have slept in the hospital bed where she was filmed in Terms of Endearment, something she alluded to in an interview with James Lipton on Inside the Actors Studio [1]. There is the old tale of Dustin Hoffman living his role while shooting Marathon Man which led to the story of Olivier’s supposed comment “Try acting my boy, it’s much simpler”. Then there is an anecdote from Metta Spencer’s book Two Aspirins and a Comedy:

A friend of mine, a woman psychiatrist, went to a play that her son had directed. One actress played all the roles - the child, her father (who molested her) and her mother. After it was over, there was a discussion with the audience, many of whom had also experienced such abuse. The actress had no opportunity to get out of her roles before participating in the discussion. As a result, she had a psychiatric breakdown. My friend and her son stayed with her for two days because she was suicidal. She got into the roles and couldn't get out. (Spencer 2006)

Whether any of these stories is true or not is not necessarily important because it reflects a particular attitude about the work actors do: there is a certain expectation that actors subsume themselves in order to “be” the person or thing they are to perform. This is nothing new. As far back as the ancient Greeks, actors were believed to be in some way possessed by the roles they performed. Some, like Plato, even felt that due to this kind of sorcery actors ought not to be part of his new Republic. (Roach 1993: 137)

In the chapter “Text and Stage”, from the book, A Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology, Franco Ruffini makes the following statement in a section about role type and character:

The actor and character are the two poles of a duality which have been the subject of considerable historical and theoretical investigation. The actor who enters the character; the character which, adapting itself, enters the actor; the actor and the character which meet at a point halfway between them; the actor who fixes and maintains a critical distance from his character…these are only a few of the more familiar formulations regarding this issue. (Barba and Savarese 2005: 274)

Ruffini goes on to describe the relationship between actor and character as an interaction that is not truly present until the performance. He likens it to the moment at dusk when one looks out to “where the sky and the sea meet” (Barba and Savarese 2005: 274) and the two appear to blend. During performance the actor and character blend, “making the spectator see the optical illusion of an identity.” (Barba and Savarese 2005: 274). He concludes by noting that while this is the case for the spectator, it is not necessarily the case for the actor. The actor does not have the luxury of distance. The actor must create the illusion for the audience. But for this to be the case, the actor must surely see a distinct separation between the character and his/her personal self. This is not always an easy distinction to make.

Hollis, in his essay “Of Masks and Men”, expresses the problem of defining the distinction this way:

We may be inclined to view actors as donning and doffing masks like hats but that is not the only way to conceptualize theatre. Acting can also be regarded less as representation than as expression…that of the human agent playing himself in the drama of his own life. Here the self cannot be the mask alone, as the point of the analogy is to deny that we are merely beings-for-others; nor can it be the man alone, without destroying the analogy; so it must be some fusion of man and mask…meanwhile plays have scripts, plots, and conventions, which constrain and enable the players in their interpretation of character…There is no one-sided truth about theatre either. (Carrithers 1985: 222)

There have been many other attempts to define the relationship between the actors and roles they perform. Weissman in Creativity in the Theater, describes actors as having “excessive inner needs for, and urgent insatiable gratifications from, exhibiting themselves.” (Weissman, 1965:11). Because actors have failed to develop a normal sense of identity, Weissman asserts that “the actor’s roles give him repeated opportunities to temporarily secure a self-image” (Weissman 1965: 12). Essentially, there is a psychological point of view that says that actors are in search of an identity that they can “become” due to an inadequate sense of their own personal identities.

Another particular area of exploration regards emotion and how the apparent necessity of reproducing it is to be achieved. Denis Diderot is best known for his approach to the question of the role of emotion in acting. In his book The Paradox of Acting, he asked whether actors ought to personally feel the emotion of the role or instead detach themselves from the emotion and portray what looks like the emotion to the audience while feeling nothing themselves. His conclusion was that the best actors do not feel the emotions but remain “detached” (Diderot 1957: 53). The actor who was completely immersed and felt the emotions was in danger of becoming lost on stage where the actor portraying the emotion was always in control. Then there are the more recent views like that put forward by Richard Hornby in The End of Acting where he argues that there are two kinds of emotion: “real” and “imagined”. “Real” emotions are essentially those that are felt everyday which tend to be quickly aroused, yet slow to subside. “Imagined” emotions, which he believes are part of the actor’s world, are defined as the feelings about the circumstance. The actor imagines what it might feel like to be in the circumstance of the character. The “imagined” emotion can be powerfully felt, yet not affected by “unconscious repression mechanisms” which can often inhibit “real” emotion. He argues that the “aesthetic distance” of imaginary emotions allow for “contemplation” and “shaping” of the emotion, which he believes is what the actor is doing (Hornby 1992: 121).

The question of emotion and its place in performance remains controversial. Many Western acting texts put forth the idea that the emotion can be recalled from the actor’s personal past and then molded into something “real” to be performed; Strasberg’s use of Affective Memory, for instance. But do actors utilize these sorts of tools in their practice? What do actors think about their relationships with the roles/characters they perform? Where do actors place emotion in terms of its importance in performance?

This work will utilize responses to the survey [2] in order to focus on these questions in an effort to discover what actors think about the notion that they “become” their character/role and where emotion falls in relation to that notion. In order to achieve this, it is important to get a sense of how the respondents characterize any perceived differences between their personal “selves” and the character/role “selves”. The survey, therefore, asked a number of questions designed to allow the respondents to describe the relationships they have with the things they perform. Question #51 asks:

51. During the performance, it is important for you to believe what is happening to your character in order to properly portray it.

This is then followed by a scaled response of 5 choices:

1 - Not at all. I don't believe any of it.

2 - Maybe in a given moment, but not all the time.

3 - Sometimes. It depends on the role and what the playwright has written.

4 - Most of the time I really do believe.

5 - Absolutely. It's like it's happening to me.

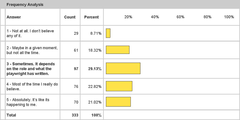

The reasoning behind this question is that an actor that is more given to “feeling” an emotion would be expected to place themselves on the higher end of the scale. We might characterize this as an “immersed/internal” performer, to use Konijn’s categorization [3]. Those respondents who place themselves on the lower end might be considered to be “portraying” an emotion. These respondents might be characterized as “detached/external”. A breakdown of the responses to question #51 for is shown in the table seen right:

For the population of 333 respondents, 72.97% place themselves on the “belief” end of the scale, with the bulk, 29.13% saying “Sometimes”. This is intriguing as it suggests that there are times when they do think it is important to believe what is happening to the character is happening to them. The comments from the questionnaire are also revealing [4]:

I am unable to shut off the actor mind completely; I have to take the audience into account. However, self-consciousness is the death of good acting. I try to stay in the moment as much as possible.”(Respondent #473049 – Answered “4 – Most of the time I really do believe on #51)

This is what moment-to-moment work is, but I never lose the awareness of the audience and the fact that I am performing

(Respondent #758263 – Answered “4 – Most of the time I really do believe on #51)

It is hard to answer that, because there are so many levels of belief and involvement. On one level, I feel I have to believe in what is happening in the moment, but on another level, I am aware of the fact that I am on stage and that I have a job to do that requires a certain degree of detachment. Otherwise, blocking and other technical elements are in danger.

(Respondent #463773 – Answered “3 - Sometimes. It depends on the role and what the playwright has written.” on #51)

This sample of comments demonstrates the variety of ideas that actors have about the issue of “belief”. The difference between an actor that marked “5” and that of an actor that marked “2” is quite wide. One says that it would be “insane” to believe while the other says that “you need” to believe. This makes for an interesting starting point in an exploration of the data as it implies that there is a wide separation in how actors might describe their relation to the role they are playing.

The next question to explore how performers relate to the role is #64. This question asks:

64. In terms of your relationship to your character, where do you fall on the scale below:

1 = My body is a neutral puppet operated from a conscious distance. I have no emotional engagement with my character.

5 = Depending on the circumstances, I step in and out of complete emotional engagement with my character.

10 = I have full engagement of emotion with my character. I feel what my character is feeling.

The question was designed to get a further sense of how the respondents view themselves in relation to the role they are performing.

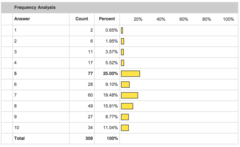

As the graph, right, makes clear, the respondents say that they tend towards engagement with their character with a mere 11.69% of the respondents on the “no emotional engagement” end of the scale. The comments are quite telling. For instance, two respondents that placed themselves as “7” on the scale said:

Because I relate so closely with my characters (by finding what I have in common with them and choosing my actions accordingly) I cannot help but feel an attachment with them. As a result, they become like very real projections of myself, and I find it difficult to keep a distance (not that I would want to... this is a way for me to discover things about myself I didn't necessarily know). (Respondent #492571)

I believe the emotional state is an important part of portraying the character. But I am not able to completely be the character.

(Respondent #758147)

While one respondent who chose “3” on the scale said:

i am always aware of what my body is doing. very rarely are the emotions i am portraying what i am actually feeling

(Respondent #489552)

A respondent that chose “2” on the scale remarked:

I have little emotional engagement with my character, but I often experience a heightened emotional state before/when/after performing. I wouldn't agree either that my body is a 'neutral puppet', even if many of the exercises that I use to prepare for performance depend on a purely physical exploration. In terms of emotional connection with the character, however, I'm definitely at the low end of the scale. (Respondent #1159693)

Finally, a respondent that chose “5” said:

I can't choose just one end of this spectrum - a relationship with a character has to be at both ends simultaneously. If I have full engagement of emotion, absolutely all the time, then I wouldn't be able to remember lines and blocking, and I wouldn't be able to remember to cheat out and project - and act. So a little part of my brain has to be at a conscious distance, overseeing the decidedly un-neutral puppet of my body as it acts. The best moments are those of complete emotional engagement with my character, when I'm really feeling with her - but even at those moments, the puppetmaster part of my brain reminds me that I need to stay focused and not get too caught up, or too self-congratulatory. (Respondent #457027)

While another said:

I use whatever tool is required at the time to get the story across to the audience. (Respondent #758159)

This scale will become more important as we continue to look at how the respondents describe their relationships to their characters because it reinforces the data from question #51.

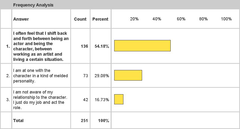

Question #64 is itself further supported by the data from question #119. This question came much later in the survey after all of the questions about performance had been asked. It was placed there in order to see if there would be any change in opinion after the respondents had been thinking further about their relation to the role they are playing. In this case, the respondents were asked to choose between three statements:

In performance, which statement best describes your relationship to your character?

1 - I often feel that I shift back and forth between being an actor and being the character, between working as an artist and living a certain situation.

2 - I am at one with the character in a kind of melded personality.

3 - I am not aware of my relationship to the character. I just do my job and act the role.

Based on the responses to question #64, it could be assumed that the first choice would be picked most often since the highest percentage of respondents placed themselves in the middle of the scale. It could be further assumed that based on previous responses, the second choice would come second here as this population tends to place itself on the engaged end of the scale. As the graph, right, demonstrates, these assumptions are warranted as the 16.73% of the respondents that chose the third option is quite close to the percentage of respondents that placed themselves on the non-engaged end of the scale in question #64 (11.81%).

The idea of shifting back and forth between the character and the actor will become more significant as further questions are examined. Here we are seeing an early indication that there might be a perceived separation between the actor and the character and that engagement with this character might be a moment to moment event.

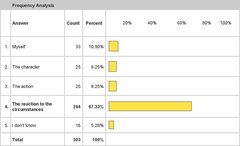

Questions #s 66 and 68 examine the actor/character relation further by asking the actor to define where they think emotions shown on stage are coming from:

66. If your character is supposed to be angry, where does the anger come from? (choose the answer that best applies)

1 - Myself

2 - The Character

3 - The action

4 - The reaction to the circumstances

5 - I don’t know

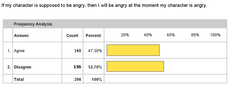

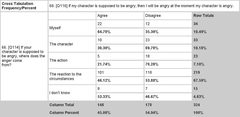

68. If my character is supposed to be angry, then I will be angry at the moment my character is angry.

1 - Agree

2 - Disagree

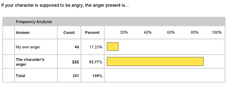

With these two questions, we begin to see some interesting data. For #66, the overwhelming response is that the emotion (in this case anger) comes from the reaction to the circumstances, as the table, right, demonstrates.

Only 10.90% of the respondents feel that the anger comes from themselves and even fewer feel that it comes from the character or the action. This is not out of line with the responses to the previous questions. The respondents appear to be saying that while they do tend to engage with their character, it is the circumstances of the scene that create the emotions. Where we see a real divergence is in #68.

Here the divide between actors is evenly split. Nearly half agree and just over half disagree. As noted in statistical analysis, in a semantic differential question like this one, the closer the answers are to an even 50/50 split, the wider the diversity of opinion in a given population. [5] We can look at this split more closely, in order to see where the diversity lies. We can compare the responses from both questions to see where a respondent that agreed or disagreed with the statement about whether they would be personally angry when the character is angry (question #68), says that anger comes from (question #66). As the relational chart, right, demonstrates, there is nothing in particular that stands out. For the most part, the respondents are evenly split on the issue of whether they will be angry when the character is regardless of where the emotion in the scene is coming from.

The only significant split is between those respondents that say they are angry when the character is and also said that the anger comes from “Myself”. Here we see that 64.70% say that they are angry when the character is angry. As significant as this might seem, it only makes up 6.79% of the total responses. In fact it is only 22 actors in total. So while it might be possible to say that respondents who say that the anger in a scene comes from themselves and they feel it personally, the population that say this in response to this question is far too small to make that kind of conclusion.

Fortunately, there are several more questions that delve into the notion of the actor’s relation to the character and its emotions. Question #s 94, 95 and 96 attempt to get closer to the heart of the matter by asking directly about the actors’ relationship to the character and its emotions.

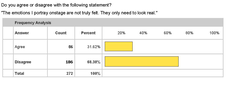

94. Do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

"The emotions I portray onstage are not truly felt. They only need to look real."

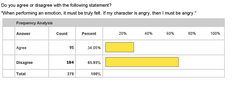

95. Do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

"When performing an emotion, it must be truly felt. If my character is angry, then I must be angry."

96. If your character is supposed to be angry, the anger present is...

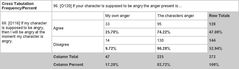

My own anger.

The character’s anger.

Together, these three questions ought to provide better insight into the relation an actor has to her/his character. It might be presumed that the respondents who disagree with the first statement, stating that the emotion does need to be “truly felt” will agree with the second (“If the character is angry then I will be angry”) and choose the first response in the third (“My own anger”). This would reinforce the idea that actors in this study sample tend more towards an immersion view of acting since the training in the Method or early Stanislavsky would tend to support this (see Hetzler, 2007, chapter 1). This would also tend to be in agreement with the data from question #64 asking about engagement – the higher up the scale the respondent placed him/herself, the more likely that this should be the case. However, the results (see charts, right) show something far more interesting.

It is quite clear that the bulk of the respondents do not feel that it is acceptable for emotions to merely “look real” (68.38%). At the same time, they do not feel that when the character is angry, they too are angry (65.95%). So how can this be? If the anger present is, in the actor’s mind “real”, how can it not be their own personal anger? This is answered by question #96 which shows that the respondents believe that that emotion presented is the character’s and not their own (82.77%). What we discover is that among the actors who responded, there is a distinct separation between the actor and the role they are playing, while at the same time they feel that the emotions called for must be real. This is further supported by examining the cross tabulation comparing question #68 to question #96 seen right.

Here we see that even though there is a near even split between the respondents that say they are angry when the character is angry and those that are not (#68), the two groups overwhelmingly (225 to 47) say that the emotion present is not their own but is the character’s (#96). This seeming contradiction suggests that there is a specific delineation for actors where they can separate the emotions of the character from their own personal emotions.

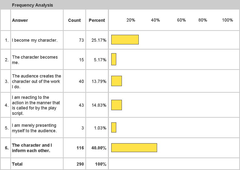

This notion of separation is brought more into further light when the data from an earlier question is added to the mix. Question #79 asks:

Which of the following choices best describes your relation to your role?

In this case, there is a very definite idea about the relation of the respondent to the role.

In the chart, right, a full 40.00% feel that the character and the actor inform each other while the next highest group feels that they “become” the character (25.17%). This dovetails with the data from question #64 where the respondents placed themselves on the 10 point scale. Whether they describe their relation to the character as being a feedback process of informing each other, or a stepping in and out of engagement (as defined by question #119), it appears that within this population of actors, there is a distinct feeling of separation, as the respondents state that they are aware of both themselves and the character at the same time.

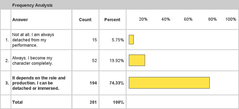

This is further supported by question #110:

How important is it to become your character?

1 - Not at all. I’m always detached from my performance.

2 - Always. I become my character completely.

3 - It depends on the role and production. I can be detached or immersed.

In this instance, we see a reinforcement of question #79 where the majority of respondents said that the actor and character inform each other. As the graph demonstrates the majority of respondents chose “It depends…"

This is not unexpected given that the bulk of the respondents put themselves in the middle of the ten-point scale with a tendency towards the immersion end and said that they shift back and forth. The comments on this question bear this out:

There were also some interesting comments about the separation between the actor and the character. The comment that follows came from a respondent that chose “Always”:

It is important to become the character ON stage and to be yourself OFF of it.(Respondent #480516)

This comment is reflective of the kinds of statements made by the respondents during the interview process,in which the nature of the separation between the actor and character and this awareness of the separation was explored in more depth. The participants were asked a series of questions that stemmed directly from the responses gathered on the survey questions that have been explored above. The goal was to shed additional light on the questionnaire data. It was hoped that by offering the respondents the opportunity to discuss the idea of the relation to character, they would be more drawn out and provide more insight into the answers on the questionnaire. As will be shown, a majority of the actors interviewed said that there is a distinct separation between the character and themselves. They also stated that while the emotions are indeed “real” and that they stem from within themselves, they are not always truly “felt” when they are performing. In fact, very few say that they carry the emotions of a scene with them when they exit the stage. Instead, as the questionnaire data suggests, the interviewees generally believe that it is the character feeling the emotion and not themselves. What follows is an examination of how the interviewees responded to questions about how they relate to the character.

It is important to be totally engaged with the character, but not to become the character completely. (Respondent #476065 - No Answer)

I can't possibly be a dinosaur in real life, but onstage, yes. So go figure. (Respondent #458815 – Answered “It Depends)

Impt. to portray the character honestly, but not to the point of detachment from the ever changing influences. (Respondent #462207 – Answered “Always”)

As above, I'm not there to live the character--I'm there to communicate him to others. That is a skill, not a state of mind. (Respondent #875542 – Answered “Not at all”)

The degree to which I truly, in-the-moment believe that what is happening to the character is absolutely real for the character is directly proportional to the degree to which the audiencee will suspend its disbelief. If I as my character do not believe that what is happening in the world of the play is real, the audience won't believe it either. (Respondent #459812 – Answered “5 - Absolutely. It's like it's happening to me” on #51)

You really need to believe in what is happening as much as you [could] good [sic], so you can forget about the audience.

(Respondent #507036 - Answered “5 - Absolutely. It's like it's happening to me” on #51)

If I actually believed it I would be insane. I know the difference between reality and fantasy. (Respondent #876354 – Answered “2 - Maybe in a given moment, but not all the time.” on #51)

For me a continuous awareness of the audience, no matter how small, is essential. If I surrender completely to a character, I don't think any part would be left to include the audience

(Respondent #1162050 – Answered “2 - Maybe in a given moment, but not all the time.” On #51)

Total immersion can lead to problems like sudden improv and cockiness wheras if you have a duality it seems truthful, acting is acting not being (Respondent #970659 – Answered “It Depends”)

I prefer immersion in the imaginary circumstances, but this does not suit every project. There is always a certain engagement with something however, whether it be an activity, an imagined image, or even with a line I speak. Very dependent on the project. (Respondent #1141784 – Answered “It Depends”)

[2] The full questionnaire can be found here, or by linking from the Conclusion or Works Cited pages.

[4] Please note that the comments are included here in the exact manner in which they were written on the questionnaire. Therefore, all spelling and punctuation errors have been included. All responses to the questionnaire were anonymous. The respondents are referred to by the number assigned by the survey software.

[5] For more on question types and how they are described, see Alreck & Settle’s chapter 4, “Composing Questions”, Salant & Dillman’s chapter 6 “Writing Good Questions”, and Oppenheim’s chapter 8, “Question Wording”. It should be noted that some of the kinds of questions noted in this section are given slightly different names in different books, depending on the authors.