Temporality and Gamification

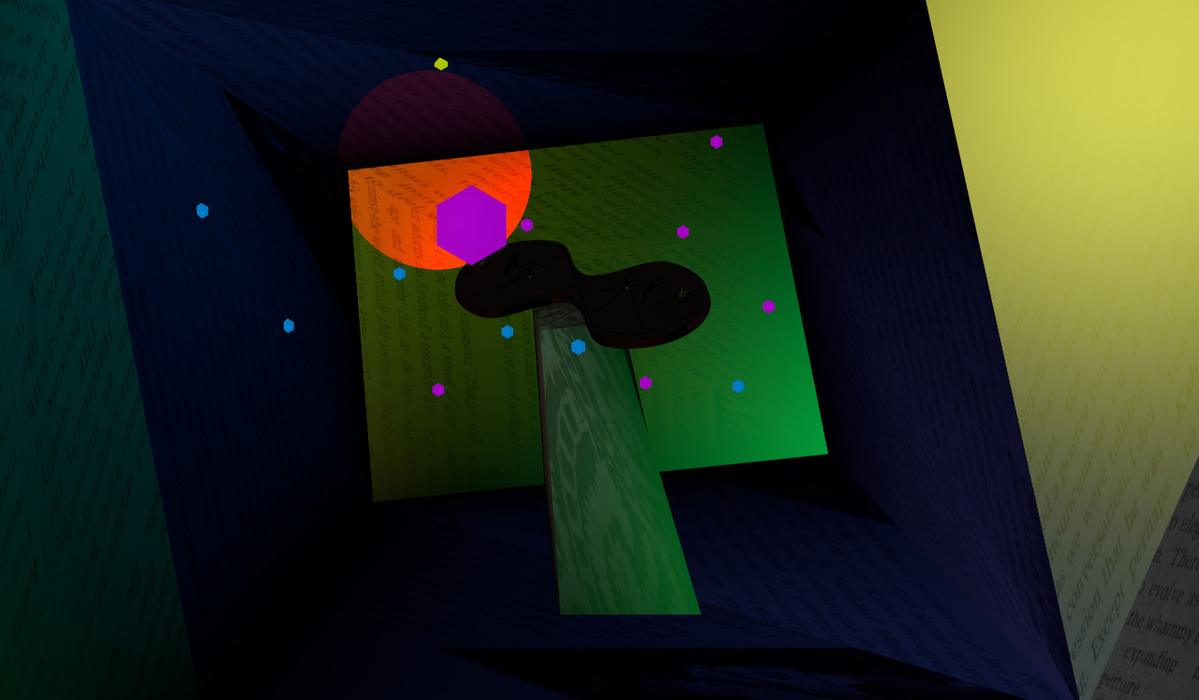

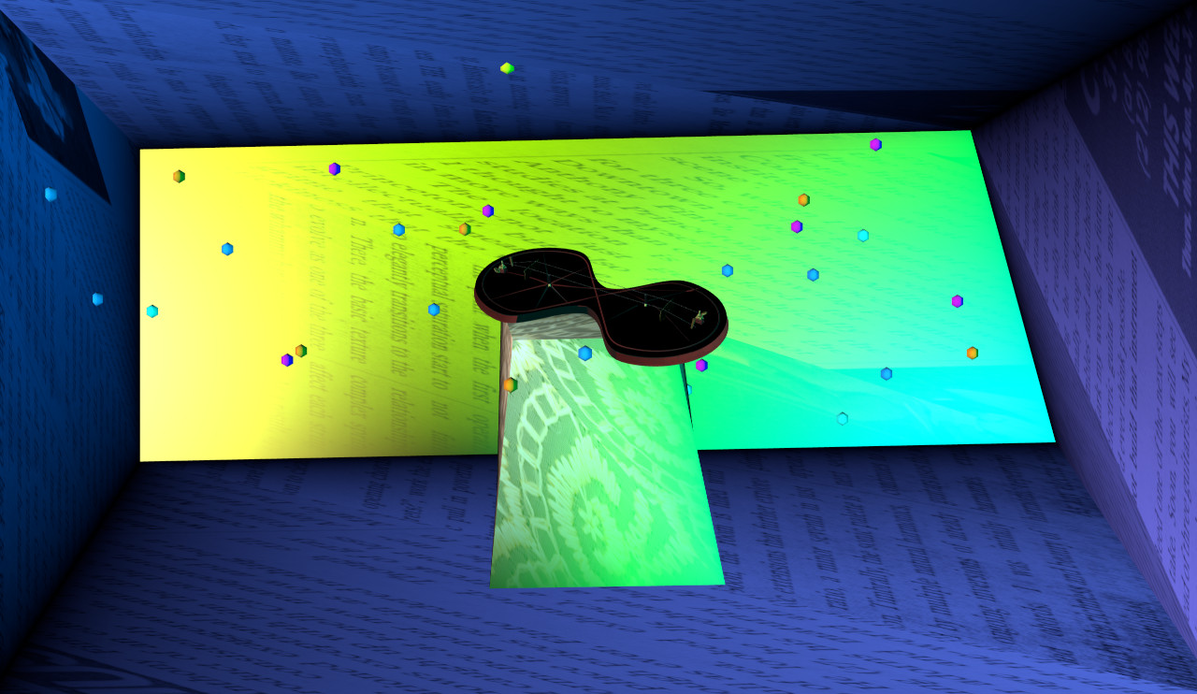

The positions of the balls are stored and upon repeated visits (as long as they take place at the same browser) they are reinstated. Furthermore, with every visit a different color is assigned to the balls. When the balls are scanned by the spot-light during the 'dark-mode' each color will produce a different sound. Hence it is encouraged to start the scene repeatedly and to produce different series of balls.

Once a large number of balls in different colors has been collected, scanning over them produces a rich and varied percussive texture.

The balls have a live-span of a day and as they 'age' they are more and more pale when being reloaded. Since the color also affects the sound when they are scanned, the overall sonic result will keep changing as the hours go by.

The overall design provides a situation in which the user is:

- encouraged to spend larger time-intervals in the 'dark-mode', even though keeping the mouth open and navigating the spot-light easily becomes physically tiresome or unpleasant. This is rewarded by the possibility to accumulate many balls, which later leads to more interesting musical results when scanning over them with the light.

- it is also encouraged to revisit the environment within less than 24 hours. This will lead to balls of different colors and as a result, a richer musical result when scanning over them.

The 'aging' of the balls and their eventual disappearance have been implemented to create the impression that the experience of the environment is unique each time it is reloaded. However, this uniqueness is not the result of random operations that automatically create variations of the same situation, but it is a direct result of the user's actions.

Conclusion

This net-art project presents a simple scenario, a room once lit and once darkened, where the user can place balls that produce sounds when being rescanned. However, a number of features have been built in that are rather unusual and that are supposed to generate particular experiences of liveness.

Liveness of Embodiment

As described above, the interaction and navigation are only taking place by moving one's head and opening or closing the mouth. This physically tiring interface has been chosen to (1) create an intimate entanglement between the user's body and the environment and (2) create a bodily involvement that requires a form of physical effort.

When computers are discussed as instruments of musical performance it is often criticised that interactions with computers in general do not require any physical effort (Schloss 2003, Ostertag 2002), which is in contrast to traditional instruments where a direct correspondance between physical effort and sonic result can be observed. Through the described use of face-tracking as an interface, physical effort is therefore reintroduced, although in a non-traditional manner. In my opinion this quality of physical involvement has the potential of evoking a "liveness of embodyment" in the user, that creates a strong bond with the virtual place, or to use Henri Lefebvre's terminology: a 'lived place' in the virtual.

Liveness of Temporality

Contrary to the net-art projects "Why Frets? - Touch" or "Why Frets? - Float", which come to an end after a number of interactions have happened and certain stages have passed, this net-art project can go on indefinitely. However, a unique sense of temporality has been created by storing the state of the project when it is quit and reloading it when returning to it. However, the balls have a fixed lifetime of 24 hours and during those hours they are 'aging'.

What is created by this scenario I would like to refer to as a "liveness of temporality". Contrary to Sanden's "temporal liveness" which describes when an audience experiences a performance in the very moment when it is performed, "liveness of temporality" is meant to describe a liveness which originates in an awareness that time is passing and that states that have been obtained can not be preserved.

The combination of these two modes of liveness stood in the center of the exploration of this net-art page and have led to its particular quality.

References:

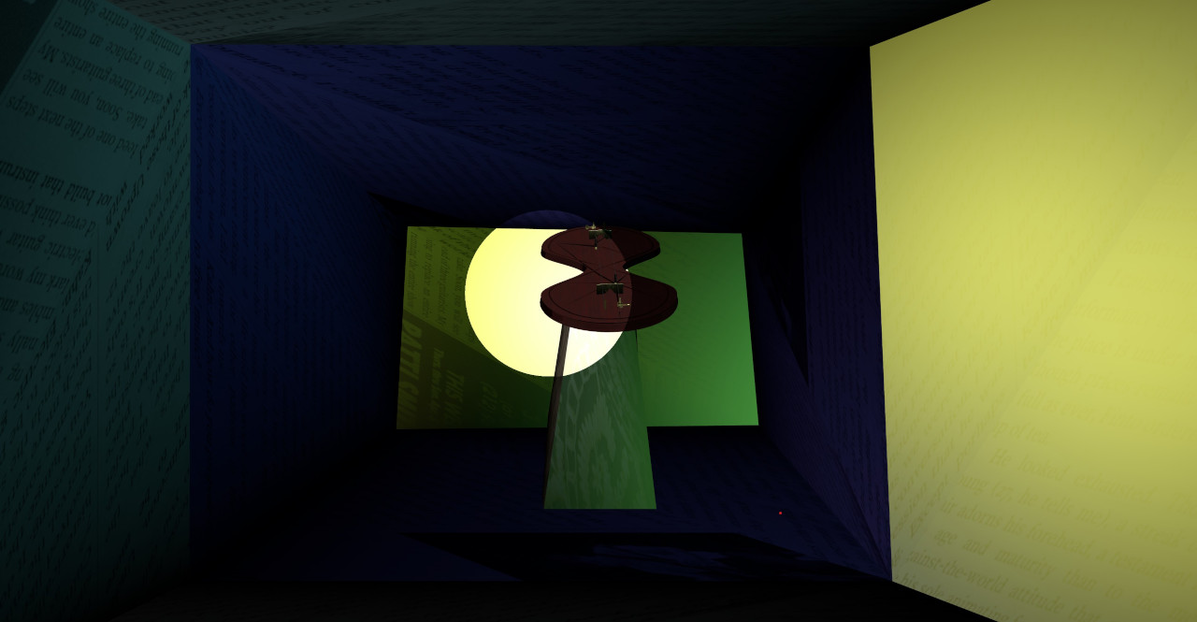

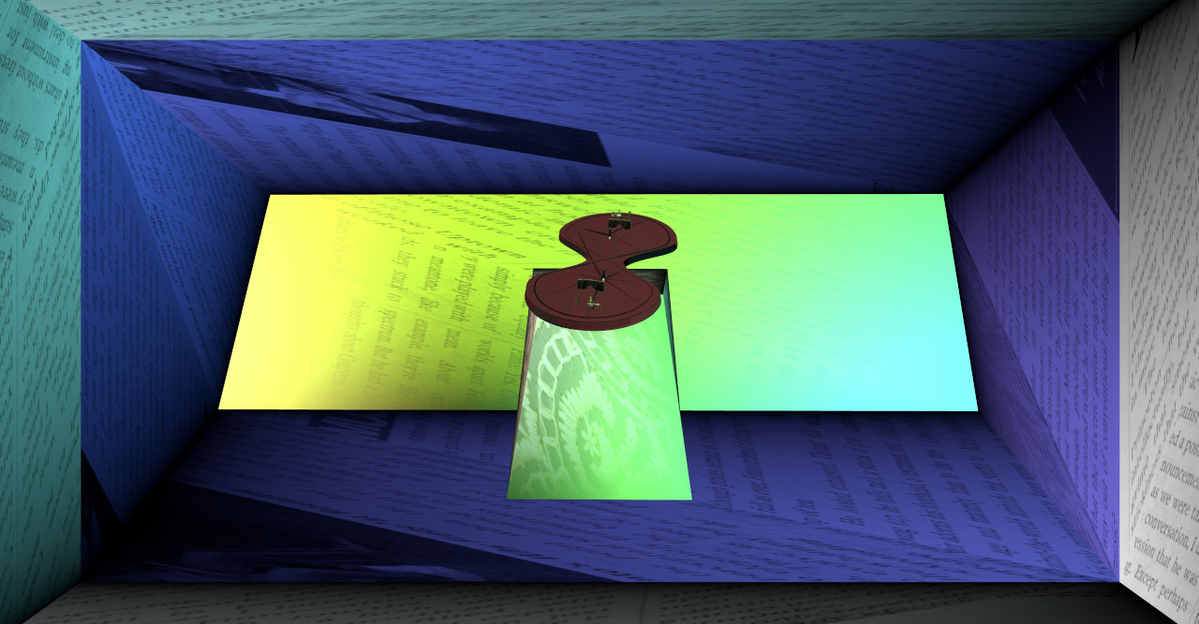

Fig.3: the 'dark-mode', instanciated by opening the mough - the room turns dark and a spot-light becomes visible that can be moved by controlling the head-position.

"Why Frets? – FACE"

This page is an investigation of an embodied interface. The question of embodyment in virtual environments has be dealt with extensively, mostly in the context of game designs and specifically in the representations of players through avatars (Harrer 2018, Jayemanne 2017, Klevjer 2022).

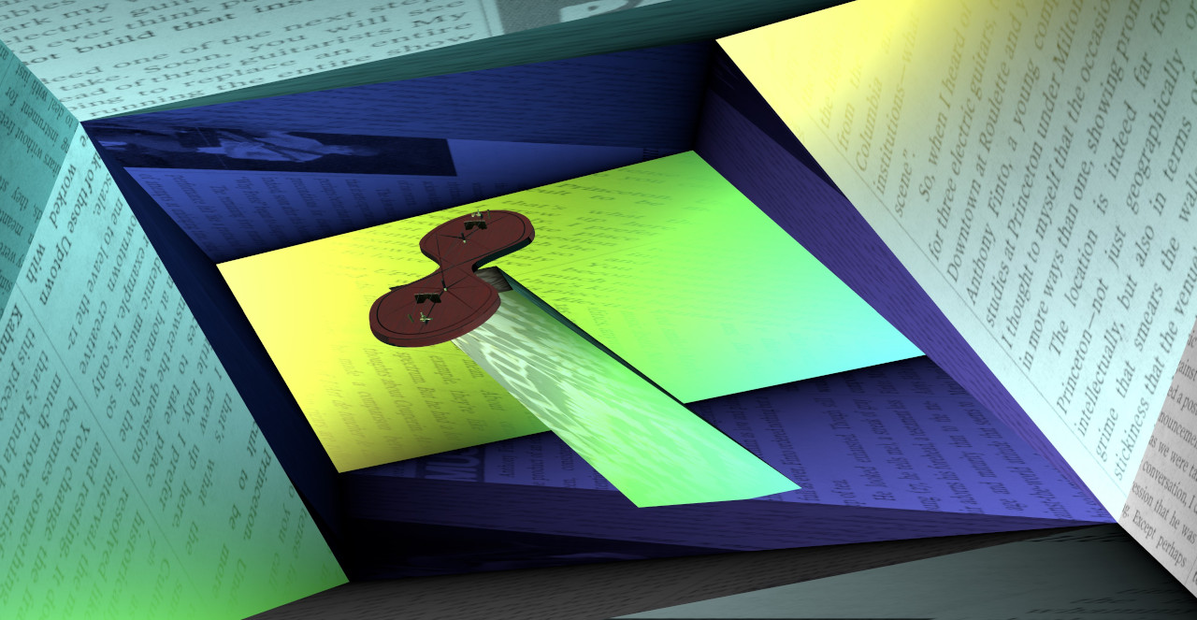

In this website, however, embodyment is not applied through avatars or other representations of the user. Instead, face-tracking1 is used and applied to a virtual 3D space. When opening the net-art page, a simple 3D space is displayed, which is contorted according to the user's head position. When tilting the head left, right, up and down, the geometry of the space is distorted. Furthermore, when the user opens his or her mouth the light condition in the space changes and goes dark while a narrow spotlight becomes visible. By tilting the head, the beam of the spot can be moved and when resting in one place, after a few seconds a ball is "ejected" that travels from the position of the point of view through the space until it hits a wall.

In the following paragraphs the functionalities and aesthetic choices are explained in detail.

Direkt link: whyfretsface.iem.sh

Inter-FACE

All interactions with the 3D space take place without using the hands, solely by moving the head, grimassing the face and opening and closing the mouth. This is obtained by using face tracking.

In the initial state, the position of the head and - to a smaller extent - the expression of the face control the shape of the space. Tilting the head, for example strongly distort the shaoe of the space, as can be seen in Fig. 1 and 2.

Once the user opens his or her mouth, the room get dark and a spot-light is turned on (henceforth referred to as the 'dark-mode' as opposed to the former 'light-mode'). The position of this spot-light can again be controlled by the head position.Tilting the head gently to the left makes it move to the left and vice-versa when tilting the head to the left. When lifting the head, the spot-light moves up, when lowering the head, it goes down.

Instead of trying to create a virtual character that the user identifies with, here the attempt was to dissolve the duality of the displayed environment and the user. Since the space deforms with every movement of the user, nothing in the virtual space is external to the user's representation.

Physical fatigue

Controlling the position of the spot-light during the 'dark-mode' requires subtle control of the head position. At the same time the mouth has to be kept open, because as soon as it is closed, the 'light-mode' returns, with the entire room being lit up and no spot-light visible.

The control of the spot light can become physically straining. This fatigue that can happen has deliberatly been taken into account in order to create a direct physical involvement of the user.

Ejecting balls

When during 'dark-mode' the user keeps the spot-light in one position, the light of the spot-light gradually turns red and after 5 seconds a ball is ejected from the user's point of view, that travels throught the virtual space to the position where the spot-light was positioned. The ball gets stuck at the first object that it encounters on its flight - usually the opposite wall. This is also when the sonic layer of the scene is started. The flying ball produces sound and upon impact, a harmonic texture is started, which henceforth modulates its timbre as the room is reshaped.

After moving the spot-light again, the user can trigger another ball. This process can be repeated as often as the user pleases. On every impact of a following ball, the sonic harmonic texture changes.

Illuminating older balls

When the spot-light passes over older immobile balls, they light up and produce a bell-like sound. Hence, producing a larger number of balls is 'rewarded' by making them produce sounds whenever the spot-light passes over them.