While the Laments used in this study span several European nations, their respective subject matter and manner of presentation share much in common. Creative methodologies and practices were exchanged across borders and inspiration gained through the sharing of not only music, but also the literary and visual arts. The balance of aesthetic and social values regarding grief as represented in these non-musical forms help to illustrate the relationship to grief in the 17th century and provide examples of what kinds of emotional responses may be presented in musical Laments.

2.1 Grief in literary works

Just as there were clear guidelines for funerary practices, there were also societal conventions as to how grief should be manifested and expressed according to an individual’s social status and situation. Men, particularly those of the upper classes, were expected to show only moderate displays of grief, while women and children were deemed unable to keep their emotions in check.1 These generalized conventions are perhaps most striking in the dramatic works, as a single event can garner reactions and dialogue from several different perspectives. William Shakespeare’s (1564-1616) well-known tragedy, Hamlet! (first published in 1603) provides several such examples.

In this first excerpt from Act 4, Scene 5, Ophelia has succumbed to madness after learning of the death of her father Polonius. Ophelia seeks out Queen Gertrude (who has been warned of the young woman’s deteriorating mental state) and sings nonsensically before speaking to the queen directly about her grief:

OPHELIA:

I hope all will be well. We must be patient. But I

cannot choose but weep to think they should lay him I’th’

cold ground. My brother shall know of it. And so I thank

you for your good counsel. Come, my coach! Good night,

ladies, good night. Sweet ladies, good night, good night.2

Ophelia’s words make it clear that she views the act of weeping in response to the death of her father as a normal reaction. Her forementioned madness also suggests a mental incapacity to deal with the overwhelming grief, and is an affliction often given to female characters following a traumatic experience.3 This immediate acceptance of an outward display of emotion is distinctive from her male counterparts, as demonstrated in this second excerpt from Act 4, Scene 7. Here, Ophelia’s brother Laertes has just learned from Queen Gertrude that Ophelia has drowned.

LAERTES:

Too much of water have thou, poor Ophelia,

And therefore I forbid my tears. But yet,

It is our trick; nature her custom holds.

Let shame say what it will.

[He weeps.]4

In this passage, Laertes acknowledges a sense of shame that comes with allowing himself to cry, contrary to Ophelia’s earlier acceptance of the same act. He elaborates by blaming human nature for his momentary loss of control, attempting to justify the shame of this shortcoming. This need to explain emotional actions is in keeping with the masculine expectations of the time, and is later heighted by Hamlet in Act 5, Scene 1. Hamlet, who is romantically involved with Ophelia, does not learn of her death until he happens upon her burial proceedings. After watching Laertes leap into the grave to hold his sister one last time, Hamlet makes his presence known and jumps in after him.

HAMLET:

Comes, show me what thou’lt do.

Woo’t weep? Woo’t fight? Woo’t tear thyself?

Woo’t drink up eisil? Eat a crocodile?

I’ll do’t. Dost thou come here to whine?

To outface me with leaping in her grave?

Be buried quick with her, and so will I.

And if thou prate of mountains let them throw

Millions of acres on us, till our ground,

Singeing his pate against the burning zone,

Make Ossa lika wart! Nay, an thou’lt mouth,

I’ll rant as well as thou.5

Hamlet’s dramatic interjection functions less as an expression of personal lamentation than as an act of defiance against Laertes’ formal display of devotion.6 He disparages Laertes for showing him up as the main mourner, when Hamlet believes that he himself, as Ophelia’s romantic partner, should be showing the most pomp at the proceedings. Where mental deterioration was a common occurrence for female characters in lament-worthy scenarios, a call to action in response to these scenarios was often utilised by male characters. According to Jennifer Lodine Chaffey, “[…] calls to revenge in early modern drama are often based in the idea that by directing mourning into masculine action, individuals could both outwardly show their sorrow and purge themselves of grief”.7 While these outward displays of passion were socially accepted, it was also recognized by some that they were not necessarily the best way to help an individual heal,8 although the call to action could potentially help dispel some of the negative emotions.

This theme of supressing inner grief is also demonstrated in the work of another 17th-century English writer: poet John Donne (1572-1631). His poem, “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” (written c. 1611-1612 and first published in 1633, two years after Donne’s death) suggests acceptance and faith as a suitable alternative to grief:

As virtuous men pass mildly away,

And whisper to their souls to go,

Whilst some of their sad friends do say

The breath goes now, and some say, No:

So let us melt, and make no noise,

No tear-floods, nor sigh tempests move;

‘Twere profanation of our joys

To tell the laity our love.9

Although this poem is written from the perspective of two lovers who are about to part ways, it also defines a response to the death of a “virtuous [man]” as gentle and lacking in “tear-floods” and “sigh tempests”. While this is meant to reassure the speaker’s lover, there is an underlying (and perhaps unconscious on the part of Donne) message that responses to grief should be mild, and that one should have faith in the eventual reunion of two separated parties, whether on earth or in heaven.10

That is not to say that male literary subjects were never given leave to weep. French poet Molière (c. 1622 – 1673) sent a sonnet to fellow writer François de La Mothe Le Vayer following the death of his son. The poem, “À M. La Mothe le Vayer sur la mort de son fils” (“To Mr. La Mothe le Vayer on the death of his son”), advises Monsieur le Vayer to let the tears come, and reassures him that they are reasonable given the circumstances:

Aux larmes, Le Vayer, laisse tes yeux ouverts :

Ton deuil est raisonnable, encor qu'il soit extrême ;

Et, lorsque pour toujours on perd ce que tu perds,

La Sagesse, crois-moi, peut pleurer elle-même.

On se propose à tort cent préceptes divers

Pour vouloir, d'un oeil sec, voir mourir ce qu'on aime ;

L'effort en est barbare aux yeux de l'univers

Et c'est brutalité plus que vertu suprême.

On sait bien que les pleurs ne ramèneront pas

Ce cher fils que t'enlève un imprévu trépas ;

Mais la perte, par là, n'en est pas moins cruelle.

Ses vertus de chacun le faisaient révérer ;

Il avait le coeur grand, l'esprit beau, l'âme belle ;

Et ce sont des sujets à toujours le pleurer,11

To tears, Le Vayer, leave your eyes open:

Your mourning is reasonable, even though it is extreme;

And, when forever one loses what you lost

Wisdom, believe me, can cry herself.

One proposes wrongly a hundred different warrants

To want, with a dry eye, to see what one loves die;

The effort is barbaric to the eyes of the universe

And it is brutality more than supreme virtue.

One knows well that the tears won’t bring you back

This dear son taken from you by unforeseen death;

But the loss, for that, is no less cruel.

His every virtue made him revered;

He had a great heart, a beautiful mind, a beautiful soul;

And these are subjects to always mourn him.12

Molière and his work focused on morality and his own personal ethics as opposed to Christian values,13 clarifying why he speaks directly to the cruel loss of the son, as opposed to the eventual reunion of Le Vayer and his son in heaven. Where Donne disparaged the shedding of tears, Molière describes the act of supressing them to be “barbaric to the eyes of the universe”.

While Molière’s sonnet encourages a man to let his emotions take over, English poet Aphra Behn (1640-1689) brings a strong, decisive, and emotionally secure female voice in “Angellica’s Lament”, taken from The Rover. Behn is heralded as one of the first feminist writers to make a living through her writing, and her work often outlines the strength of female sexuality and its ability to help men access and express their emotions.14 “Angellica’s Lament” from Act 5, Scene 1, outlines the loss of power of a woman when betrayed by a lover:

Had I remained in innocent security,

I should have thought all men were born my slaves,

And worn my power like lightning in my eyes,

To have destroyed at pleasure when offended.

--- But when love held the mirror, the undeceiving glass

Reflected all the weakness of my soul, and made me know

My richest treasure being lost, my honour,

All the remaining spoil could not be worth

The conqueror’s care of value.

--- Oh how I fell like a long worshipped idol

Discovering all the cheat.15

Despite the excerpt being commonly referred to as a ‘Lament’, it glosses over expressions of sadness with a measure of objectivity. Behn never mentions any internal feelings nor the shedding of tears, and instead uses an image of “lightning in the eyes”: a simile that brings strength and stability to the female speaker. This version of lamentation acts as a reflection on what has occurred, as opposed to a loss of control resulting in an emotional display.

While there are certainly exceptions (as was demonstrated with “Angellica’s Lament”), women were generally presented as the more outwardly emotional gender in 17th-century literature.16 Although women were expected to express grief in a more emotional manner than men, overly manic and public presentations were still considered outside of the normal human practice; enough so that a character might be deemed “mad”. It is likely that these controlled representations of grieving are a result of the principles indoctrinated by the most important text in Europe during the 17th century: the Bible.

2.2 Grief in the Bible

With most people practicing some form of Christianity, the Holy Bible was undoubtedly the most influential piece of literature in 17th-century Europe. Religion acted as a singular unifying factor within the daily lives of peoples from all social classes. Gentlemen attended morning and evening services in their private chapels; children and servants would devote much of their time to private prayers;17 and families from all walks of life would attend Sunday services in their respective parishes.

When James I became the King of England in 1603, he authorized a new English translation of the Bible to enforce a level of conformity within the different sects of the Church.18 The resulting ‘Authorized King James Bible’ was first published in 1611, and served not only as a common ground on which people could discuss scripture, but also as an inadvertent means of spreading the patterns of speech of the English language.19 As such, the Bible serves as an important source of inspiration for the presentation of musical Laments, regardless of whether they are sacred or secular in nature. While the texts used in this chapter are those of the King James Bible, it should be noted that the ‘Vulgate’ was the Bible used by the Catholic Church, still in its original Latin form. After examining both versions of the Biblical texts, I concluded that there are not enough differences in the presentation of the narratives to warrant the inclusion of the Latin texts within this study.

The book of Lamentations begins with the destruction of Jerusalem, told through the personification of the city. As with the majority of personified cities in literature, Jerusalem is given feminine pronouns: “She weepeth sore in the night, and her tears are on her cheeks: among all her lovers she hath none to comfort her: all her friends have dealt treacherously with her, they are become her enemies”.20 Throughout the first part of the book of Lamentations, themes of uncontrollable weeping are again connected with the female gender, coupled with a secondary image of a solitary widow. The personification of Jerusalem expresses an overarching sense of grief within just a few short lines, as the reader can immediately relate to the motifs presented. This display of emotion starts to dissipate as Lamentations continues and the prophet Jeremiah speaks directly to God. Through his invocation, Jeremiah creates a sense of distance from his own emotions, particularly as he speaks directly to the actions (or lack thereof) of God: “Wherefore dost thou forget us for ever, and forsake us so long time? / Turn thou us unto thee, O LORD, and we shall be turned; renew our days as of old. / But thou hast utterly rejected us; thou art very wroth against us.”21 Despite being referred to as the ‘weeping prophet’, Jeremiah’s response to the fall of Jerusalem is rooted in action as opposed to emotion. Jeremiah calls on God to restore Jerusalem while voicing his displeasure towards Him, similar to how Hamlet transformed his own grief into words of action against Laertes.

Even when concerning the death of Christ, there is a level of emotional restraint represented in the texts. Of the four books detailing the Crucifixion, only Luke and John make mention of mourners and outward displays of grief. Luke recalls the people who were present for the crucifixion, including the women who lamented him prior to his death: “And there followed him a great company of people, and of women, which also bewailed & lamented him. / But Iesus turning unto them, said, / Daughters of Hierusalem, weepe not for me, but weepe for your selves, and for your children.”22

Again, we see that the mourners are specifically listed as female, and it is the Daughters of Jerusalem who are assigned to weep. While these women are encouraged to show their grief, Jesus asks that they not weep specifically for him; Jesus also asks for the same emotional restraint from the Virgin Mary in the book of John. The following excerpt from John comes after Jesus’ death, when Mary visits the Sepulchre and finds that his body is missing:

But Mary stood without at the sepulchre, weeping: & as shee wept, she stouped downe and looked into the Sepulchre, / And seeth two Angels in white, sitting, the one at the head, and the other at the feete, where the body of Iesus had layen: / And they say unto her, Woman, why weepest thou? Shee saith unto them, Because they haue taken away my Lord, and I know not where they have laied him. / And when she had thus said, she turned herselfe backe, and saw Iesus standing, and knew not that it was Iesus. / Iesus saith unto her, Woman, why weepest thou? whom seekest thou? She supposing him to be the gardiner, saith unto him, Sir, if thou have borne him hence, tell me where thou hast laied him, and I will take him away. / Iesus saith unto her, Mary. She turned herselfe, and saith unto him, Rabboni, which is to say, Master.23

Although there are clear interjections of Mary’s weeping, emotional phrasing is excluded in favour of a simple narrative. This aloofness allows the emphasis to be placed on the events themselves and replaces personal quandaries with the concept of faith guiding individuals in God’s plan.

2.3 Sacred artwork

Despite the objective approach to the presentation of events within the text of the Bible, numerous artworks depicting the emotions surrounding these same circumstances were produced at this time. Like the majority of 17th-century artwork, great care was taken on the part of the artist to produce works that imitated life. Artists worked ad vivum (from life), using live models to achieve realistic portrayals of movement and energy within the still image.24 The figures’ positions were staged to express a certain value or emotion25 and emphasized by liberal use of chiaroscuro.26

Caravaggio’s Deposizione was commissioned as an altar piece for the Chapel of the Pietà at the church of 'Santa Maria in Vallicella' in Rome and, like many of his works, exemplifies the use of chiaroscuro. As Christ is being laid in the tomb, he is attended by the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, John, Nicodemus, and Mary Cleophas. The background is in complete darkness, bringing the illuminated figures into stark relief. Although the body of Christ is the main focal point for this work, it is the expressions of his attendants that bring the work to life. John and Nicodemus hunch over to support the body, directing the energy of the entire party downwards. Nicodemus’ face is cast in shadow obscuring his expression, while John’s is turned away as though he is looking out of the painting to explain the event to passersby. The Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene both have their heads bowed in a gesture of defeat, pain, and humility. Mary Cleophas’ extended arms and open mouth express outward lamentation and convey a sense of high dramatic tension.27

The works of Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn were heavily influenced by Caravaggio, although the two never met. Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem utilises the same interplay of dark and light, although in a softer manner than Caravaggio’s Deposizione. The image of Jeremiah is illuminated by an unknown light source, with the burning city barely visible in the background. This choice to put Jeremiah in the foreground emphasizes his internal monologue from the latter part of the book of Lamentations. The angling of the prophet downwards creates the same direction of energy seen in the work by Caravaggio, but the exclusion of the visual focal point transforms the posture into one of pensive stoicism.

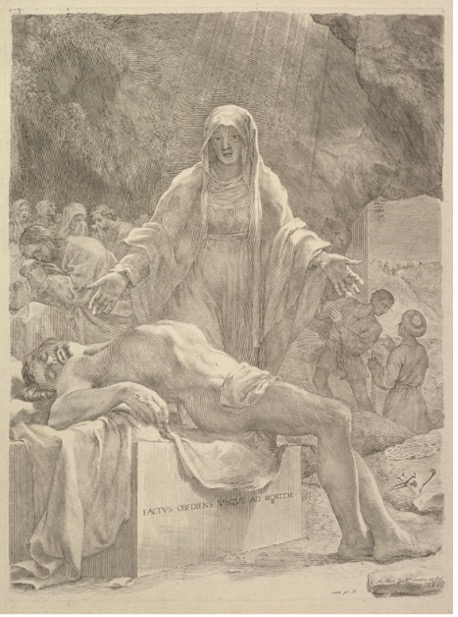

Claude Mellan’s (1598-1688) Lamentation includes a rarity in sacred artwork – the depiction of weeping men. To the left of the Virgin Mary are gathered a group of mourners (likely those mentioned in Luke 23:27), those whose heads are veiled are women, and the remainder are distinguished as men by their facial hair. These figures are not concerned with action as John and Nicodemus are; instead, they bow their heads in grief. In this depiction, the Virgin Mary is the one giving the motion towards action, gesturing with open arms towards the body. The inscription on the plinth reads ‘factus obediens usque ad mortem’: become obedient until death.

In Italy, artwork depicting the Virgin Mary right after the death of Jesus was categorized under a distinct umbrella term: pietà (literally translated as ‘pity’).28 The majority of pietà in the 17th century were paintings, usually commissioned by wealthy patrons for display in churches or in their own private chapels. While the pietà often consists of the Virgin Mary holding the body of Christ, the genre also extends to works that feature the Virgin Mary alone, as well as those that include other Biblical figures mourning alongside her.

Pietà with the Three Marys offers excellent examples of different physical gestures of grief, although the mourning of Christ by this group of women is not recounted in the Bible.29 While Caravaggio used chiaroscuro to illuminate Christ and the faces of his attendants, Carracci (1560-1609) uses muted colours to diminish certain elements of the painting. The greyish pallor of the body is not only an indicator of Christ’s death, but also serves to draw attention to the brighter faces of the figures surrounding him. The blonde woman (possibly Mary Cleophas) is supporting the Virgin Mary, who acts as a mirror of the corpse in her grief and is painted with the same muted palette, while turning to the older woman in green for guidance. The older woman, despite being cast in shadow, is the most active in this scene, with her outstretched arms and open mouth an urgent need to help the distressed Virgin. Mary Magdalene is the only figure directed towards the body, and her physicality conveys the clearest sense of despair. As with Cleophas in Deposizione, her hands are raised, but with the pairing of this gesture with a crouched position and downward gaze, the gesture becomes more intimate and focused. She also exhibits a furrowed brow and tensed jaw, indications of her grief despite a lack of visible tears.

Jusepe de Ribera’s (1591-1652) pietà is one of the few to include true indicators of weeping, such as tears and red-rimmed eyes. Mater Dolorosa uses the same black backdrop characterized by Caravaggio, with the almost imperceptible black cloak fading into the darkness, drawing all light and attention to Mary’s mournful expression and clasped hands. The positioning of the hands up towards her face plays several different roles: firstly, to draw focus upwards to her expression; secondly, to suggest she might be using the white cloth to wipe away her tears; and finally, to illustrate the importance of prayer in this moment of grief.30

2.4 Secular artwork

Although secular artworks are not created to serve as reminders of scripture nor the importance of prayer, they exhibit many of the same attributes as their sacred counterparts. Rembrandt’s A Woman Weeping has the same bowed posture as Mary Magdalene in Deposizione and is framed in a similar fashion to Carracci’s Mater Dolorosa. An example of Rembrandt’s later style, the subject is painted with a range of muted brown and gold hues and broad brushstrokes,31 and she maintains the same pensive energy as seen in Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem thanks to her careful positioning and downward gaze. Although her hand brings her veiling to her face, there are no visible tears to wipe away.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Cleopatra uses the same token of a handkerchief to suggest the weeping of the figure in the far background. The second shadowed woman, however, does not exhibit the usual markers of grief. Despite her posture being slightly bent over, her face maintains an upwards openness and her furrowed brow is not accompanied by other markers of facial tension. The resulting expression is more serene than grief-stricken, and her softened gaze gives an aura of peace to the body of Cleopatra. This more gentile approach brings a different depth to the theme of grief, particularly for female subjects.

2.5 Summarizing the 17th century relationship with grief, as demonstrated through art

As exhibited in these creative works, there is a level of restraint associated with the expression of grief in the 17th century. Generally, men are expected to show their grief through action in lieu of weeping, and tears are instead relegated to women. The clerical presentation of grievous events in the Bible was likely a contributing factor to this expectation, as religious piety was an important part of everyday life. Grief was and is an emotion that can be stylized through the careful application of artistic techniques and emotional tokens, and it can be expected that musical Laments will follow these same patterns within their own narratives.

2.6 Grief in musical Laments

In comparison to the other artistic forms of the time, the Laments in this study most closely resemble the secular literary works, with their distinct use of the first-person perspective and an occasional removal to the third-person. Although there are instances of interjections from those who are not directly involved in the act of lamentation themselves, these secondary figures simply comment on the events and recount the emotions of the primary characters, rather than explaining the emotion or giving advice (as was seen in the works of Donne and Molière). It is therefore unsurprising that these musical Laments tended to focus on personal matters of the heart as opposed to delivering broader messages to society. In both visual artworks and musical Laments, secondary figures may be used to draw focus to a certain aspect of grievous expression. The array of different Lament-triggering events will be further examined in Chapter 3.

1. Jennifer Lodine Chaffey, “‘What is he whose grief bears such an emphasis?’ Hamlet’s Development of a Mourning Persona,” Quidditas vol. 39, art. 7 (2018): 124-125, accessed May 27, 2022, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol39/iss1/7/.

2. William Shakespeare, The tragicall historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke by William Shake-speare (London: N[icholas] L[ing] and John Trundell, 1603).

3. Stand-alone mad songs were also composed in the 17th century—Hegvold offers excellent insight into 17th-century mad songs through the collaboration of composer Henry Purcell and poet Thomas d’Urfey:

May Kristin Svanhold Hegvold, “Madness in Music,” Master's Research Exposition (Koninklijk Conservatorium: 2018), https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/299015/299016.

4. William Shakespeare, The tragicall historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke by William Shake-speare, London: N[icholas] L[ing] and John Trundell (1603).

5. Ibid.

6. While male uncontrolled emotional responses were frowned upon, formal displays of devotion were expected, particularly with the loss of a close family member or spouse. Indeed, it would be in poor taste if the man did not make a public expression of grief during these occasions, but he must always remain in control and display his emotions with a dignified (yet still genuine) delivery, as well as a level of masculine action and discourse.

7. Jennifer Lodine Chaffey, “‘What is he whose grief bears such an emphasis?’ Hamlet’s Development of a Mourning Persona,” Quidditas vol. 39, art. 7 (2018): 121-122, accessed May 27, 2022, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol39/iss1/7/.

8. Ibid, 126.

9. John Donne, “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” Poetry Foundation, accessed May 28, 2022, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44131/a-valediction-forbidding-mourning.

10. John Freccero, “Donne’s ‘Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,’” ELH 30, no. 4 (1963): 335–76, accessed May 28, 2022, https://doi.org/10.2307/2871909.

11. Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, “A M. La Mothe Le Vayer, sur la mort de son fils,” Poesie Française, accessed May 28, 2022, https://www.bonjourpoesie.fr/lesgrandsclassiques/poemes/jean_baptiste_poquelin_dit_moliere/a_m_la_mothe_le_vayer_sur_la_mort_de_son_fils.

12. English translations by Ai Horton.

13. A. Lytton Sells, “Molière and La Mothe Le Vayer,” The Modern Language Review 28, no. 4 (1933): 444, accessed May 28, 2022, https://doi.org/10.2307/3716333.

14. “Aphra Behn,” Poetry Foundation, accessed May 26, 2022, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/aphra-behn.

15. Aphra Behn, The Rover or, The Banish’d Cavaliers, London: Richard Wellington and William Lewis, (1677).

16. One should remember that the majority of published writers at this time were male, and that the works of Aphra Behn—while exceptional in their own right—were certainly overshadowed by the sheer volume of her male counterparts.

17. William Henry Snyder, “The daily religious life of England of the early 17th century,” Thesis (University of Arizona, 1935): 62, accessed May 23, 2022, https://repository.arizona.edu/bitstream/handle/10150/553244/AZU_TD_BOX338_E9791_1935_37.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

18. Kenneth Fincham and Peter Lake, “The Ecclesiastical Policy of King James I,” Journal of British Studies 24, no. 2 (1985): 179, accessed May 22, 2022, http://www.jstor.org/stable/175702.

19. Baylor University, “How the King James Bible changed the world,” Baylor Magazine (Summer 2011), accessed May 25, 2022, https://www.baylor.edu/alumni/magazine/0904/news.php?action=story&story=95758.

20. Lam 1:2 AV.

21. Lam 5:20-22 AV.

22. Lk 23:26-28 AV.

23. Jn 20:11-16 AV.

24. Sheila McTighe, “Representing from Life in Seventeenth-Century Italy,” (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 5-6.

25. Ibid, 11-12.

26. A clear contrast between light and dark within an artistic composition.

27. Musei Vaticani, “Caravaggio, Deposition,” Musei Vaticani, accessed May 31, 2022, https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/la-pinacoteca/sala-xii---secolo-xvii/caravaggio--deposizione-dalla-croce.html.

28. The most well-known example of a pietà is Michelangelo’s (1457-1564) masterpiece of the Virgin Mary holding the body of Christ, carved from a single slab of marble (completed c. 1498-1499). This work is currently housed in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

29. The National Gallery, “The Dead Christ Mourned,” The National Gallery, accessed May 31, 2022, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/annibale-carracci-the-dead-christ-mourned-the-three-maries.

30. This positioning of the model is likely influenced by Titian’s version of “Mater Dolorosa” from c. 1550.

31. The Met, “Rembrandt (1601-1669): Paintings,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed June 1, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rmbt/hd_rmbt.htm.