7. Voice Meetings: short story of sound

As a part of this research project, I have also wanted to explore artistic possibilities using a continuum of voice sounds ranging from natural narrative speech to “abstract”, processed sound, within the same performance. I wanted to see if it was possible, or rather, artistically meaningful to implement the role of the storyteller in a musical expression. In this chapter I will look briefly at the following:

- My motivations, artistic ideas and research questions.

- The methods used and some of the challenges involved in researching a performance.

- Some of the important findings and developments that emerged throughout the process.

Due to the nature of the project, a performance is not easily represented by anything else apart from the live situation. I will now therefore start by providing just two short excerpts from the performance that was held for students in 2010.The performance they are taken from was an important part of a collaborative research project, which I will return to in the following. You will hear short extracts from the Norwegian story and an English summary will be provided later on in this chapter, while the Norwegian text and a translation of it will be found in Appendix nr. 2.

Example VII, 1: Excerpt 1:

Example VII, 2 : Excerpt 2:

7.1 Background, motivation, research question and artistic idea

Part of my motivation for this project was my experience of a greater nearness between myself and the audience when I was talking to them and telling them something (as I would in a teaching or lecturing situation), compared to the musical performance situation, when I was reciting lyrics or poems, singing, or working with sound in different ways. I already had musical references (Laurie Anderson, Amy X Neuburg, David Moss) that were absolutely part of my inspiration, but first and foremost the project was motivated by these experiences of nearness and distance in a performing situation. The difference in the experience of nearness was not only related to the situation of “not fulfilling the expected singer’s role”, as discussed earlier (Section 4.1). First and foremost there was an experienced difference between being a musician and being a storyteller. I imagined this nearness through the act of speaking as being the result of an identifying process: if someone tells you something that you can identify with, through your own experience and/or knowledge, you start to know the person in a different way than before, identifying with the person through your shared experiences. I wanted to find out if the nearness created by taking the role of the storyteller could also bring the audience closer to a musical experience and the performance as a whole. This was also motivated by the wish to open up those parts of my musical expression that for some audiences might be experienced as being too abstract or alien. Working with improvised and sometimes experimental music, I sometimes feel responsible for making music for “expert audiences”. The use of electronic processing, the improvised character and the focus on sound rather than the traditional musical elements, is something that excites me, but: could bringing in a more communicative element open up this musical world for new audiences?

When this project turned into a collaborative research project, together with musicologist Andreas Bergsland (see Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2), I needed a more specific research question, and it was formulated like this:

‟Can taking the role of the storyteller in a vocal musical performance create an identifying process between the performer and the audience? Can this process open up for the musical expression as a whole?”

I will discuss some of the problems associated with this research question later, but this was my starting point and my motivation.

Developing the artistic idea

It was important for me that the story/text should be rather concrete, and come from me, I wanted it to be my personal story. This was because I wanted to come as close as possible to telling something that mattered to me, something beyond being a “performer of text”. For the same reason I wanted the story to be in my own language, Norwegian. I collaborated with the writer Siri Gjære, telling her stories based on memories from my own life. From these stories she created several texts, and the one I chose to go further with was created from my memories of my late grandmother. (The text I used can be found in the appendix, in both Norwegian and in English). I see this choice of text – a very personal story with pictures from everyday life – as creating a starting point for this project that is rather different from works I have heard from artists such as Laurie Anderson (ex Walking and Falling (Big Science 1982)), Pamela Z (ex. Baggage Allowance 2010) and David Moss (ex. the sound poem “What About Performance, Herr Wittgenstein” 2002.)[47] With this text as my starting point, I developed a kind of “musical monologue”.

The experience I acquired from working with this performance was in many ways very different to that acquired from my other projects due to the importance of understanding the text semantically and of telling the “story” in a natural way. The text is formed as “scenes”, like memories that pop up in your mind with no particular logical or chronological connections. Still, it has a dramaturgy that leads us forward. It starts as being somewhat open: I am sitting in a car, just experiencing the feeling of driving at night –I am probably driving to my grandmother’s house. Then there are different descriptions of meeting – or hearing from – my grandmother, about her house, the letters she wrote, how she fed the cats in the backyard, how she spoke on the phone. And all the time there are small details that provide us with an impression of her personality as being a warm, caring and generous person. The last section also contains a poetic reflection on love, life and death. In the end a car arrives at my grandparents’ house. The “underlying drama”, as some of the audience in my “expert group” called it, lies in the fact that she is no longer here, and in all the grief and sorrow that are connected to the loss of someone like that – and in the fact that this is the story of our lives – we lose the ones we love. And we die ourselves -from others that we love and are loved by.

The text material here is not something I wanted to “play around” with, except in the shorter sequences. The music has to connect to the story, so even though it has been improvised to some degree, the components, the character and the form of the whole piece have been planned - at least for now. I started out by creating musical scenarios in connection with each section of the story. They were produced through a process of improvising and trying out ideas, initially in smaller sections, without devoting too much consideration to the overall form. After this, the sections were put together and revised several times. The nature of the text was, as stated, very important, and it was challenging to find out what I felt might work with it from a musical point of view. I wanted the storyteller’s role to mix with the other roles in a natural way, and in a few places I wanted to transform gradually between the roles. Further, an important part of this process was to find out how the music could be transformed or shifted from section to section, both musically and technically, in order to make it “flow”. I had to rehearse the technical solutions, the timing had to be precise and my focus on the storytelling could not be disturbed by technical manoeuvres.

Musically, I worked with various parameters, roles and functions, as described in Chapter 4. Sometimes I also made use of the option of taking “my grandmother’s role” and imitating her dialect and typical expressions, both in pre-recorded sound samples and in real time.

During the first period of developing and adjusting the performance, I received valuable feedback and guidance from the author/singer/actor Siri Gjære, who created the text, from the writer/dramaturge Tale Næss, and from my research collaborator Andreas Bergsland.

7.2 Research collaboration and methods

While working on this project, it has been important for me to envisage the audience as being part of the performance. The relationship with the audience has actually been part of my artistic idea, because this idea came from my experience of different situations with people rather than from a genuine musical experience. Therefore it was important to examine the audience’s experience in the developing process of the performance. I realised very early on that in order to gain access to a kind of “unbiased” knowledge in this respect I would need help in examining this experience in a more systematic and distanced way than I could on my own. (Being the performer, it is sometimes hard to obtain comments from the audience which are not filtered by politeness or personal relations). In this project I have therefore, as already mentioned, been cooperating with NTNU researcher Andreas Bergsland (see Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2). This took place in a specific research project called Voice Meetings, which started in 2010 and which will continue after the end of my artistic research project.[48] This project represents a rather unique model for cooperation: it is designed to feed artistic development and at the same time collect information about the audience’s experience of a vocal performance using live electronics. For me, my cooperation with Bergsland represents an extension of my possibilities as an “artistic researcher”. An article on this research can be found in Appendix no. 4

7.2 .1 Working methods

After I had developed the first version of the performance, the investigation started. What we did was to stage multiple performances in different contexts, all including some form of audience feedback. The first performance was held in a small meeting room, while the final two were held in two different black boxes. All the performances were audio and video recorded.

Performing for (blindfolded) students at the DMMH, Trondheim, 2010. Photo: Andreas Schille.

During the two first performances we gathered the audience's responses in three different ways[49]:

1) As open written feedback, no questions or guidelines.

2) As a structured, guided questionnaire[50].

3) As focus group interviews, audio and video recorded[51].

For the first two performances the audience was divided into two groups, one “seeing” and one blindfolded, and this gave us the possibility of investigating the impact of my visual appearance. This was an important part of Andreas Bergsland’s research where he wanted to compare the listeners’ experiences of live versus recorded electroacoustic music (where you listen without seeing the source of the sound). It was also interesting for me to know more about how the visual impression influenced the concert experience.

The last performance took place in a more realistic concert setting, a public symposium that provided an opportunity for audience comments and questions after the performance.

The questions asked in the interviews were related to:

- The role of the text/story as part of the whole experience

- The process of identification between performer and audience

- The experiences of ‟naturalness” and of ‟alienation”

Bergsland has been organising and using this material for analytical studies, while I have been using both the material and Bergsland's findings to feed the artistic development of the performance.[52]

7.2.2 Researching a performance – some challenges

Before I go into some of the findings and observations, it seems necessary to point out some of the challenges involved in doing research on a performance, especially when investigating performative aspects such as the emotional and physical experiences of the audience. For example, the information we obtained from the audience during the two first rounds was probably influenced by:

- The setting of the performance as a research project: the audience knew that they were a part of a research project and that they would be interviewed after the performance. This probably had an impact on how they perceived it.

- The choice of “test” audience: during the first round a very informed group of interested and educated participants; during the second round a group of students from the Queen Maud University College of Early Childhood Education (DMMH) – mostly women in their 20s.

- The individual interpretations of the questions asked[53]

The third round was part of an open symposium at Teaterhuset Avant Garden in Trondheim, which was also held in a rather special context: an interested and probably well-informed theatre audience, in a setting where oral responses after the performance were wanted and expected. This experience points to the fact that a “neutral” audience, and a “neutral” setting, are of course an illusion. And this also applies to the “real world”, as I will show later.

7.3 Findings and observations

A performance will, in a sense, always exist in as many versions as there are people experiencing it. So there will be few exact “truths” to find. We will necessarily find observations that are related to the particular group of individuals responding to our questions, and to the particular situation. Still, with 24 persons, as in the second round, we had enough information to enable us to investigate some of the tendencies in the group. I will look here at the findings from the two first performances separately.

7.3.1 First session - findings and artistic developments

The first session, which was actually a test round designed to prepare for the second, supplied us with a lot of useful information. Because this was a test round, the information was only roughly analysed. Most important for me was the fact that the group (of nine) could identify with the story. They experienced that the story and the music connected – and was perceived as a whole. Some of the feedback motivated, or at least confirmed, my own need for making changes or adjustments to the performance, which I did before the second round:

- One important change concerned the balance between the text and the music. By starting with the text alone in this first version, I directed the focus to the story immediately. This made it hard for both me, and the audience, to experience the music as something more than a comment on the text. Only towards the end did the music take on a more important role. Starting the performance with music and sound in the second version, I experienced that this allowed greater focus to be placed on the sounds and music throughout the piece.

- Further feedback indicated that the content of the performance was perceived as taking place within an expressional “comfort zone”, and there was a call for more dynamics connected to the “underlying emotional drama” in the text, especially regarding the last section of the text where I speak about death. (As mentioned, this was a kind of “expert” audience with very competent comments!) I realised that I had been afraid of taking the musical expression “too far”, afraid of breaking the connection between the music and the text. This feedback encouraged me to create a more dramatic, dark sequence and to make use of an emotional potential that is more connected to the initial narrative than expressed through it.

7.3.2 Second session - findings and artistic developments

The amount of research material derived from the second round was more extensive, and this material was analysed more systematically. In presentations of the project we have found it useful to illustrate some of the findings with quotations taken from the collected material.[54] The quotations are taken from interviews with members of the audience after they experienced the performance, translated from Norwegian. I will now look at some of these findings and discuss, along the way, how they have had an impact on my artistic development, and how the research led to further reflections about the project as such.

Identification with the “story” and the importance of the text:

- About 45% of the audience, both “blind” and “seeing”, identified with parts of the narrative in the performance:

“I was in a car – I was driving it [laughter], with three kids in the back seat. It was raining [waving her hand to imitate the windshield wiper], and then I, like, arrived at the grandmother’s, who was my grandmother, and”

“I almost had a film rolling on the inside of my eyes, it was, like, always something that reminded me of my own childhood."

(Students, DMMH)

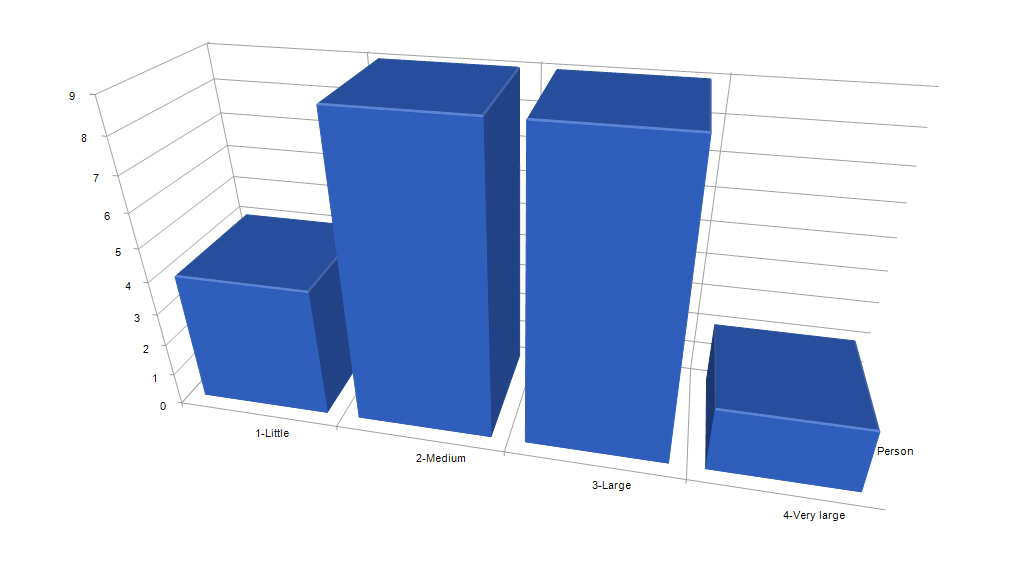

- The importance of the narrative for the experience as a whole, varied from medium to very important, for 83% of the audience (see the figure below):

Figure 7.1, from the presentation held at “Lydhørt”, Music Technology Days in Trondheim, October 2011

“The narrative was very important for me, since it was the most tangible I could get a hold on. It was the narrative that caught me those times when I was falling out and was starting to think of something else.”

“To me, language made it all appear a bit more coherent, because there was something that linked up, since she went on approximately where she left off after the sounds/sung memories.”

(Students DMMH)

After analysing the material from the second round, I realised that my research question about identification was not a very precise one and that it was difficult to answer. What did I actually intend to find out? About half of the audience could identify with the narrative, the “story”, but the majority found it important, or at least an integrated part of the whole performance. So what does it mean to identify with a story? How do I separate this from the experience of identifying with the person telling the story? Maybe that is what I was thinking about, trying to understand my different experiences of nearness; when somebody is telling you something, you can easily identify with the act of telling something or being told something. In order to examine this closer, I realise that I should have had another performance to compare it with, where I did not adopt the role of the storyteller. And maybe even a third performance, deliberately choosing a story that would be very unfamiliar to the audience. In any case, this is a difficult and complex research area, which needs further investigation.

Another problem with my research question is, as I have mentioned earlier (Section 7.2): there is never a neutral audience. My question in some ways implies that there is, and that there could be a general experience, transferrable to “all kinds of audiences”. The research material also confirmed the weakness inherent in this implied generalisation, by revealing great differences in how the performance was experienced. With this project I have been performing for very different groups; “the expert team” in the test round, the students in round two, the theatre-interested audience at the symposium – and subsequently at the Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival and at the “Lydhørt” Music Technology Days in Trondheim. Thinking about how different these audiences are, I realise that my question about “opening up for the musical expression as a whole, through an identifying process between the performer and the audience”, is rather vague and problematic. This is especially true when not directed towards a specific audience. If the question is modified to asking whether “the use of storytelling (not the identifying process as such) can open up for the musical expression as a whole”, it seems to be partly answered through the findings in the student group. Most of the students were unfamiliar with this type of music, and most of them found the story important (Fig. 7,1) for the experience as a whole.

So, after discovering the weaknesses in my research question, should I consider this a failure in my project as research? Maybe I should, if this research did not lead to any new and relevant knowledge for me. However, it certainly did. Before I go further into this, I would like to present some of the other findings, those which lead to adjustments to or to questions about parts of my work.

Audience anticipating disaster:

Several audience members anticipated that something terrible would happen after the introduction:

‟I thought it was quite scary at the beginning, and I was just thinking that something terrible was going to happen [...] They’re sitting in the car, they are going to crash – I was so certain about that.”

“Because the images I created, they...they [...] were very, like, nice or cosy, or precious, a bit like childhood memories. That’s what I felt then. But still I felt that there was this dark undertone to everything.”

(Students, DMMH)

An experience of “spookiness” right from the start, registered by several audience members in the second test round, was a bit surprising to me. There could be many reasons for this, but these comments made me reconsider the start one more time. With the adjustments made after the first round, I had wanted to bring sound into focus instead of starting with the text, but I now realised that I also wanted to introduce the audience to a sense of movement, more than the experience of wondering. So this led to a change before the third version; I used a more melodic approach and more repetitive patterns as an ongoing accompaniment. This gave the piece a better start: it felt like a monotone flow with small variations, corresponding with the first section of the text where I am driving a car at night. I wanted the audience to feel secure, and at the same time create a feeling of going somewhere.

Audience experiencing anxiety:

Many of the audience members, especially the “blind”, were frightened by one particular section of the performance:

“Then it got very uncomfortable. I was scared and insecure when the lady said ‘death’ several times and spooky sounds emerged.”

“I felt that [the voices] came closer and closer to me, and at one point; I think it was when the voices said ‘NEVER, DEATH, NO MORE WAFFLES IN ALL MY LIFE’, I noticed that I was breathing faster and I almost started crying.”

(Students, DMMH)

I was first surprised by some of the very strong experiences of fear in some parts of the performance. In retrospect, listening to the recording of the performance again, it was easier to understand, especially regarding the blindfolded listeners. This section was also often mentioned by the students in this round as an example of alienation, as a contrast to the naturalness in the storytelling. This experience has first of all increased my respect and sensibility towards the power of the sounds and the expression I work with. I have become especially aware of how I enter, and as a consequence of this, how I sometimes need to prepare these dramatic sequences for the audience. Also, in this particular performance, the way I use the very loaded word death is important, but adds to the negative experiences, and I have worked further with how this works together with the music: I try to prepare the “dramatic turn” by introducing the more noisy sounds while I am still talking about life, and I try to speak the death word, which is repeated three times, in a “neutral” manner rather than dramatically loaded one. The audience's responses have also given me the impetus to search for distinctions in more powerful and noisy expressions, such as the choice of low pitches I use on the DJFX-looper effect, how much of the low frequency area I use while filtering, and how many sharp consonants and different pitches I feed into the loop in the G/F patch. A sound can be powerful even if the sound level is low, while equally another sound does not necessarily create the power I want it to simply by virtue of being loud. This is an interesting area to explore, both in this performance and in my further artistic development.

Spooky laughter episode

Several audience members found my laughter in one section of the performance creepy and/or fake:

“Just that thing with the laughter, I didn’t think her facial expression fitted [...] with the sounds, in a way, and with her, because she looked happy, and the sounds...yeah [mimics uncomfortableness], I didn’t think they fitted at all – I thought it was very unnatural.”

“And she laughed [...] it was strange, it was strange to listen to it. It sounded fake in a way. It was like when people laugh when they have evil intentions, just like the bad guys in movies when they laugh like that, that's the worst thing I know, and The Joker, when he laughs [laughter], it disgusts me.”

(Students, DMMH)

The audience's experience of creepy laughter where this was really not intended was also a surprise. For me, this was one of the lighter and happier parts of the performance! This was also my intended expression and feeling, so the mix of my visual and auditive expression seemed ambiguous to some of the audience. In response to the question about naturalness, this incident was also commented on as being unnatural. These comments have made me work further on balancing the expression in this part, especially by adjusting the sound and character of the pre-recorded, processed sound samples.

Naturalness and alienation

Not surprisingly, the storytelling and the acoustic voice were experienced as being natural, while the most dramatic and electronic sequence was experienced as being alienating, by many members of the audience. However, we also received comments concerning the use of the voice as source material, as a “naturalising” aspect (“no pianos or things like that, recorded, just the voice…”) and further, comments on the importance of “not distorting or changing the pitch of her (my) voice”. The first comment seemingly accepts the processed sound as voice sound, while the second (more experienced with technology) might reflect things I could have done with my voice that would make it less natural. The interesting thing here is that in that case it would probably sound less natural because you could recognise the voice and hear the processing at the same time. In that way the processing technique as such would probably acquire a focus in relation to the natural voice. Several of the audience members also referred to the use of looping and delay as being more distanced than the voice alone – even when the voice sound as such is not highly processed. (“…with the echo it wasn’t her …[…] … I experienced a physical distance (telephone call sequence)…”). Furthermore, the act of singing was also commented on by some as being more distanced than speaking (“ ...when she sung, she was the sound, not herself…”).What seems clear is that the narrative and the natural voice are a very important perceptual reference for the listener in relation to the processing and the abstraction of voice sound. I also experience (as mentioned in relation to the use of this particular story), that I am exploring the premises for how I can use the processed sounds and techniques and the music created by this, without breaking the relationship with the story. I see the challenging of this relationship as being an important way for making the expression richer, more nuanced and more open for emotional duality and individual interpretation. This is therefore where the most important tensions, artistic possibilities and challenges are found in this project.

There were other important findings in the research, especially those relating to the division between the “seeing” and “blind”. These findings did not directly influence the artistic development, but I find them worth mentioning: the material showed clear tendencies towards differences in emotional and physical reactions between the two groups, the “blind” group expressing stronger emotional and physical reactions, and also more anxiety. As many as 58% of the members of the blindfolded group did not understand the nature of the performance (“Was it live, not recorded?” “ The sound engineer must have had one hell of a job!”).

In the work associated with this performance, the visual form has been discussed. The technical setup and my appearance in my different roles as storyteller, singer, soundsinger and soundmaker, are regarded as being necessary parts of the performance; my instruments and what I do. Adjustments were made in the technical setup after the two first rounds: from being gathered on a table in front of me, to being divided into two “units” with an opening in the middle, in order to create an open space between myself and the audience. (This was a great improvement which I have also included my other musical settings). In addition, I could, for example, have used videos or slides, abstracts or concrete, in my performance. I find that my choice of not bringing in another visual element is supported by some of the findings in my joint research with Bergsland: the audience, especially the listeners that were blindfolded, have reported having very clear and strong “inner pictures” triggered as a response to the music and text. I wanted the listeners to identify through the awakening of their own references and experiences in relation to the text. Introducing another visual element could possibly disturb this process. I also had in mind the simplicity of traditional storytelling: one person, sitting on a chair, telling a story. I wanted to recreate this setting in my performance (as far as possible with my instrumental setup). This choice also seems to be supported by the findings, that my presence and the feeling of nearness are very often reported as being connected to the visual impression of my face, especially my eyes, when I am telling the story.

7. 5 Integrity and audience research in an artistic process

A natural question regarding this project is that of artistic integrity versus the investigation of, and even adjustments influenced by, the audience's experience and response. The performative aspects of this project have been important for me. Part of my artistic idea here is grounded in the reception of/feedback to my performance. If there is no experienced connection between the story (teller) and the music, or if the story is experienced as being alienated, artificial, strange, I have not fulfilled my artistic idea. There are several problems associated with investigating this aspect, as discussed above. There is also a risk of flattening out the expression in the search for more clarity, where the performance becomes a “compromise”, adjusting to different feedbacks, and also a risk of “underestimating” the audience(s). This is something that I am trying to be aware of in the process of making adjustments and reconsidering choices. As mentioned before, I have to conclude that I have been guided mainly by my commitment to the text, and in some ways this has served to restrict this project. This has been, and will continue to be, the starting point for my development of “short stories of sound”: my own experience of how the text and music work together.

7. 6 Further development

7.6.1 Other stories and audiences

In the two performances from which we have collected data, and also on the basis of oral responses to the later performances at Avant Garden, Ultima and the Conference for Music Technology, there seems to be major agreement that the combination of text and music as applied in the “short story of sound” works together as a whole. This is also my own personal experience. One of the comments at the Avant Garden symposium was that the audience would like me to continue, to tell one more story. I have decided, on the basis of these experiences, that I would like to look at other peoples’ stories – rather than my personal ones – and develop other “short-stories of sound” with new text material. The question of identification, which has not been answered, might be something for me to reformulate and investigate further in this work. By using other people’s stories, I will also have a natural choice, and sometimes a responsibility, for directing the performance towards more specific audiences and venues. For example, I could use stories told by homeless people, and choose as a venue the open church that some of them are using as a shelter and a meeting point, This would elicit some interesting challenges about how I could make this work in respect of both the story’s origins and the audience's musical references – and at the same time maintain artistic integrity (as discussed above). The project as such has made me more aware of such choices. If my wish is to open up for improvised, partly experimental music through the use of the narrative and identification, the contemporary festival scene is not where this goal is challenged, or needed, the most. A conference for biologists, a seminar for teachers, a school concert – these are perhaps more important venues in which I could explore and direct this part of my work.

7.6.2 Nature is not Beautiful

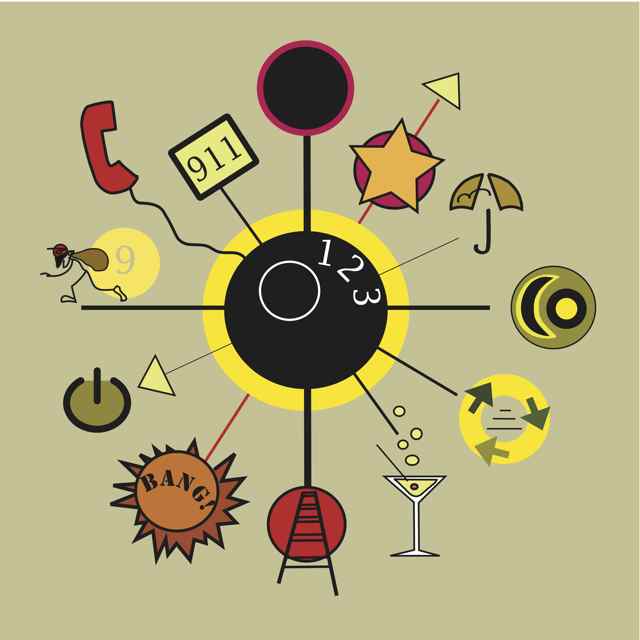

This project also led to engage in new thoughts which resulted in a production with my trio BOL: “Nature is not Beautiful”. (This project has also been described in Chapters 3 and 4.) The idea of using text as a structural framework for a performance, and of using the speaker/storyteller role intertwined with music and sound, also seemed like an exiting possibility for a trio concert format. I wanted to have a text created for us that would focus on something important and relevant, and that had a relatively clear message. We decided to focus on nature, the environment and responsibility. When the author Siri Gjære decided to write a rather metaphoric and poetic text cycle, I realised that I also wanted a more tangible text to comment on it, and that it would be hard to move between the “poetic” and the “direct” speaker in a natural way. This was resolved by recording her voice performing the poetic texts and playing back the texts as a returning component in the performance – while I took the role of “informing and commenting” with voice in real time. This solution contributed to, for us, an interesting new element in the performance as such. The overall text structure was connected to a clock/the hours passing/getting close to "deadline", and this made us want to use scenography that reflected this idea, which was made for us by artist Anne Helga Henning, Trondheim.

Scenography “Nature is not Beautiful”, Anne Helga Henning

I experienced that both the form and the character of the texts (12 separated, poetic, rather open texts with connected “comments” or ” information”) made it easier to move back and forth in the continuum between sound, music and “narrative”, than in the short stories of sound. I also experienced that the trio setting made everything less vulnerable to breaking the connection between the sound and the text; I did not have to produce everything that happened and I could go out of focus and “change roles” while the music was continuing. The performing of “comments” and “facts” gave a different feeling of nearness to the audience when compared with what I have been used to during my trio concerts. In the developing awareness of roles, this experience is an important reference to bring into the more traditional concert settings.

7.7 What new and useful knowledge has come out “Voice Meetings”?

I have already stated that the research process made me reconsider my research question, which was not, and could probably not be, answered through the research and findings. Still, I think that posing, or trying to pose the question, has led us in a specific direction and has consequently still been very useful. The material we collected was extensive, and both the reading of the questionnaires and looking at the filmed focus group interviews provided me with profound knowledge about the audience's experience. This kind of direct insight into how members of the audience expressed what had happened in their minds during the performance really widened my perspective. It felt like I had obtained a new sensitivity and respect for the personal experience of a performance, and I realised in a very tangible way how a performance can really mean something to, and do something with, the listener. I think that the kind of knowledge I obtained as a performer is somewhat similar to other practice-based knowledge. It is not necessarily “clarifying” information as such, but it produces an experiential, embodied knowledge. Still, I can sum up some important observations:

- Most of the members of the audience experienced the narrative as being an important part of the performance as such.

- The more highly processed sounds were experienced by many members as being alienating, to some degree, and there were also comments about the different degrees of nearness and naturalness, and about singing and looping creating more distance than natural speech.

- The narrative became an important point of reference, both for the audience and myself, for how the music and the use of live electronics was developed and perceived.

- The type of narrative I used (as compared to my use of lyrics in music, and also the “Nature is not Beautiful” project) made it especially important not to break the relationship between the text and the music – but to challenge it.

[47] Fümms Bö Wö Tää¨Zäa Uu: Stimmen Und Klänge Der Lautpoesie, Urs Engeler Editor, Switzerland, 2002.

[48] Performativity is a new interdisciplinary focus area at the Faculty of Humanities, NTNU, and the first part of our project also became one of the various projects that was supported financially by, and brought in for discussion and reflection by, a working group dedicated to this focus area. This has been very valuable. Further, it has become a part of Bergsland’s ongoing postdoctoral project entitled Live electronics from a performativity perspective. As described earlier, Andreas Bergsland has, in his PhD thesis entitled Experiencing Voices in Electroacoustic Music (Bergsland 2010), examined the use of voice in electroacoustic music from a listeners’ perspective.

[49] Using “mixed methods”, like this, is a way of compensating for weaknesses in each of the methods in the process of collecting information, see Appendix no 4

[50] See Appendix no.3

[51] Focus group interviews: groups consisting of 9-10 audience members were interviewed after submitting their written responses by a moderator using an interview guide (see Appendix no.3&4)

[52] After this, there have been three more performances, one of which was arranged as a continuation of this collaborative research. The material from the last one had not yet been analysed when writing this, and is therefore not part of the basis for the findings that I will refer to in this text.

[53] In research one often speaks about validity regarding these kinds of questions. Still, this method represents a higher degree of ecological validity” than most other research on performance, due to the live situation, not the video version of a performance. (Bergsland in conversation, see also Appendix no 4.).

[54] The project has been presented at three different conferences since the spring of 2011; see ”List of activities”.

[55] www.tta-sound.com

[56] For details about Åse’s performance, video clips, equipment setup and an English translation of the text, see also http://www.toneaase.no/musical-projects/

[57] The guided written response sheets and focus group questions are avaliable at http://folk.ntnu.no/andbe/voicemeetings

[58] NVivo qualitative data analysis software, 2010, QSR International Pty Ltd.

[59] This theme comprises reports of heightened or lowered focus distractions, gradually falling out of focus, etc.