Thea Koristaja

She does real everyday cleaning and then sometimes performs cleaning as art. As she works, she ponders, for example, Mary Douglas’ oft-quoted idea about dirt being ‘matter out of place’,4 and wonders if all she is doing is merely pushing dirt around. Her cleaning raises questions such as, what is dirt? How do I know something is dirt? What makes dirt dirty? However, because she is also performing cleaning as art, she thinks about the difference between art and everyday life. What makes art ‘art’? When is she ‘in’ art and when is she ‘in’ daily life?

4 Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger (London: Routledge, 2002 [1966]), p 36.

I am in the supermarket. They have a new display area with homeware-type things – candleholders, rugs, storage baskets and these grey plastic, bamboo-handled squeegees (which are very cheap at $3 each). I pick one up and hold it, flex the curved blade and wonder if it’s a good buy – whether it will be good for cleaning windows. Then I wonder whether Thea needs one. Maybe I can turn it into one of her practical art objects.

Now I am in the workshop. I’m not really dressed for it, but this won’t take long. I just want to try something. I start by filing the varnish off the handle and then realise that sanding will be more effective. Removing the varnish is the beginning of making it mine. The bamboo now has a soft finish and the slightly dusty surface of the handle is smooth to hold. Maybe I’ll paint it.

Not only am I unprepared for this work because I’m not dressed for it, but I don’t have a paintbrush in the workshop. I could just use my finger. I’ve done this before – the last time I wanted to paint but couldn’t be bothered going back inside to look for a brush. I take the first tube of acrylic paint from the container. It’s red. I like red. I squeeze a blob into an old Qantas cup and dip my finger in and start to paint the handle. The blob of paint in the bottom of the cup is more than I need because with a few strokes with my finger I’ve painted the handle. Oh well, maybe I’ll find something else to paint, to use up the paint. Maybe I should paint the end of the handle. I look for a yellow tube of acrylic. Yellow will stand out. At this point, I remember that if I’d painted the handle with white first, the red would be more brilliant. I always seem to forget this. Oh well, maybe it doesn’t have to be so bright.

I’m back in the workshop, though still not dressed for it (but at least I’m not in my pyjamas). But this time I do need to go and get a paintbrush from indoors because I want to seal the acrylic paint, and I can’t use my finger to paint the oil-based sealer on to the handle. So, I go inside and find a paintbrush. Back in the workshop, I open the can of sealer and start painting the handle with deliberate strokes back and forth. I think about Rancière.

The lines that are drawn to distinguish between different fields also create vertical distinctions, where one field is perceived as better or higher than another. Art is considered a high art; even the name ‘fine art’ suggests that it is special. Surely, we don’t have to repeat and therefore promote this hierarchical approach. Maybe there is a way of sidestepping hierarchy. Into the midst of these thoughts, Jacques Rancière inserts Jacotot’s claim that ‘all people are equally intelligent’.23 This is a direct attack on the hierarchies that I find so disturbing. The next of Jacotot’s claims, via Rancière, and one that really puzzles me, is that equality is something that is ‘neither given nor claimed, it is practiced, it is verified’.24 I am left wondering how they propose we do this. Do they mean ‘just do it’, as the slogan for a well-known sportswear brand encourages us to do? Do we start living as if we are already equal? Jacotot and Rancière propose that equality is a departure point and not a destination.25 In his essay ‘The Emancipated Spectator’, Rancière talks of the gap between teacher and pupil, actor and audience, as something that people attempt to bridge, yet because of the initial problem of thinking of it as a gap, it is never possible.26 The idea of bringing someone ‘up’ to your level means you do not believe that you already are on the same level, and in the case of the traditional teacher and the student, that gap is precisely what defines the relationship. Is it possible that the more we look at what we imagine is a gulf between art and life, or art and non-art, or true art and false, and all the gaps between the various fields of art the wider and deeper these become? Let’s look differently. Let’s start from a position of equality. Let’s not make divisions.

As I continue to paint the sealer onto the handle, I think about Adrian Tchaikovsky’s octopuses and how I could learn from them.27 In his novel Children of Ruin, there is an entire civilisation peopled by octopuses. They are confrontational beings and constantly fighting with one another, both physically and mentally. Unlike humans, they are very fluid in their allegiances, even in their principles. There will be an argument, with positions being upheld and argued, but not necessarily by the same individuals throughout the confrontation. The argument remains fixed, but the individual octopuses are easily convinced and seem to change sides quite effortlessly. The colours changing and moving across their bodies express their emotions visibly, and this means they can’t hide their feelings from each other. What if we were more like them? Not fixed in categories.

What if we try to be more like the octopuses – in our work and life?

Another challenge to the binary and confrontational view of art versus life (and my original simplistic diagram where art and life were separated by a line) comes from the 18th century Japanese dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon and his idea that art is ‘something which lies in the slender margin between the real and the unreal […] it is unreal, and yet it is not unreal; it is real, and yet it is not real’.28 This suggests a beautiful complexity with three possible spaces and a more fluid way of looking at the world, and one that really excites me. How can I weave this into my thinking?

23 Kristin Ross, ‘Translator's Introduction’, in The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation (California: Stanford University Press, 1991), p. xix.

24 Ross, p. xxii.

25 Ross, p. xix.

26 Jacques Rancière, ‘The Emancipated Spectator’, in The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2009).

27 Adrian Tchaikovsky, Children of Ruin (London: Macmillan, 2019) eBook.

28 Susan Sontag, ‘A Note on Bunraku’, in Where the Stress Falls (London: Vintage, 2003), p. 132.

I should be inside with my computer writing chapters of my doctoral thesis, but the beach here in Pärnu acts like a magnet. I wonder if it is possible to write and be outside at the same time, striding across the sand, feeling the wind and the noise of the waves. Friedrich Nietzsche instructs us to ‘Sit as little as possible; do not believe any idea that was not born in the open air and of free movement – in which the muscles do not also revel.’ 29

My father was born in Pärnu and until he left at age fourteen, it was his town. A tension builds behind my eyes, it grabs my throat, makes my cheek muscles hurt, and stops me breathing when I imagine him here walking beside me or walking to meet me. I miss him. He once wrote to my great aunt living in a tower block in Ponders End, in North London that I was thinking of doing a PhD.30

Last week in Tallinn, I went to see an exhibition of photographs at Fotografiska by Mandy Barker of plastic rubbish collected from the seas and oceans of the world. She had a collection of plastic bits and pieces picked up over the period of an hour on a beach in Ireland. Imagine the surprise if you saw something that had belonged to you. I decided to have a go too. Within seconds, I saw a piece of red something on the sand, and then one after the other small plastic pieces were waving to me, asking to be picked up.

Sonya’s mother buried her mother’s wristwatch in the sand of Pärnu beach.31 It was the 1940s. I wonder if her mother was in big trouble for that. We are ever hopeful of finding our lost things, so I said I’d keep my eye out for it. Maybe that watch is shy and if I go carefully, I will find it. The colourful plastic pieces, they weren’t shy. They kept calling me. After the red lighter with a heavily rusted top part, a fragment of orange painted wood took its place next to red. Then little green, a shard of red brick, a deformed yellow Lego block, then another green, and a piece of birch bark – not colourful or plastic, but too good to leave behind – then little blacky, shaped like a tiny Volkswagen,32 hurtling off the birch bark cliff over the head of a seashell,33 collected only because its two halves were still holding together, straight into a green plastic bottle top. Maybe Sonya’s grandmother had a little black car in the 1940s that she used to scoot around Pärnu in, and she had lost that too? Good news, Sonya! I’ve found her lost car.

Like a vacuum cleaner moving across the floor, I gather up the plastic pieces; yet unlike a vacuum cleaner, I am selective. Only colourful or interesting pieces will do for me. The beach is a tiny bit cleaner, and I turn and head back to my writing.

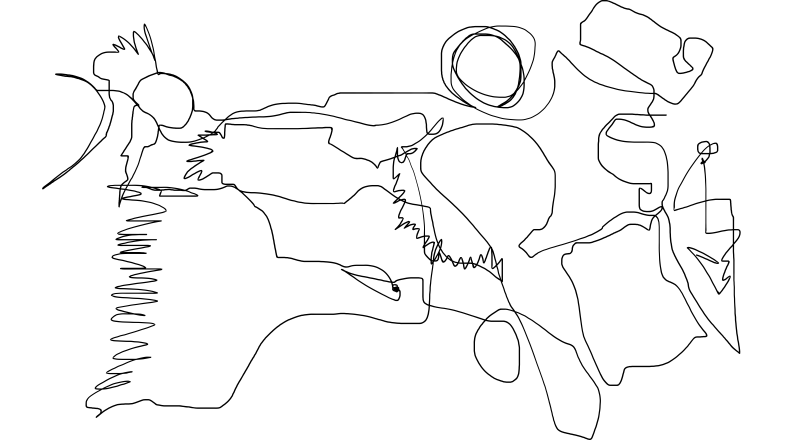

But before I write anything, I assemble the drawing. It turns out this drawing is, in fact, a story. My feet left a trail of marks in the sand and, just like the treads in the sand left by the SUV driven by the man who waved to me as he drove by, my feet had made a line drawing that went up and back along the sand. Two things I did without intending to – cleaning and drawing.

29 Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo / Complete Works, Volume Seventeen. (New York: Macmillan, 1911) <https://archive.org/details/TheCompleteWorksOfFriedrichNietzschevol.17-EcceHomo> [Accessed 23 June 2020]. Where he also wrote, ‘We [meaning himself] do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors – walking, leaping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or near the sea even when the trails become thoughtful’.

30 Olav Pihlak, Undated private letter written to Johanna Nõmm.

31 Sonya Voumard, Facebook 2020. ‘My mum buried her mum’s watch in the sand at Pärnu in the 1940s…’

32 It is on Sonya’s suggestion that the black plastic piece became a Volkswagen.

33 This is taken directly from a comment in Facebook by Bronwyn Hine based on the photograph of the collected plastic pieces. She wrote, ‘Little blacky is a car, of course, and it's hurtled off a cliff. High drama’.

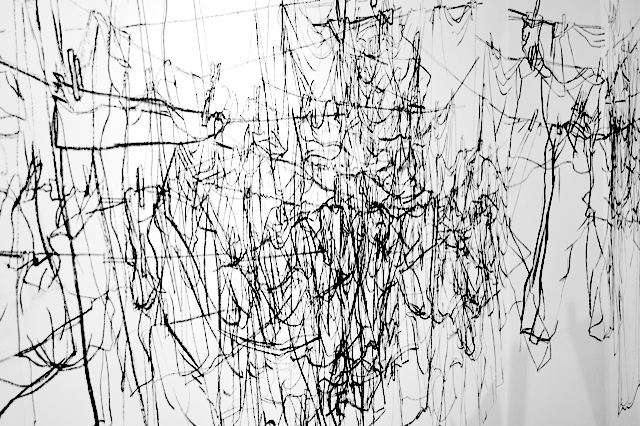

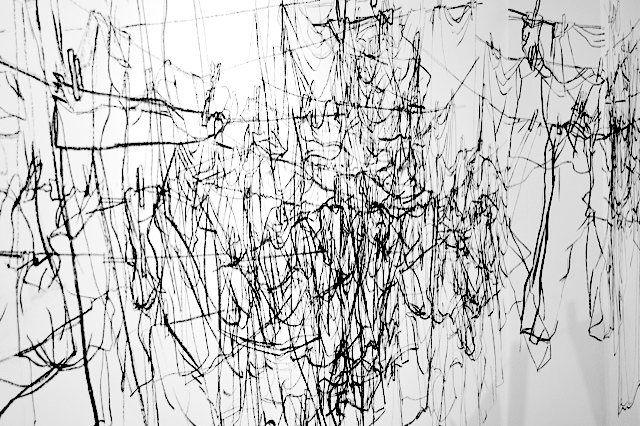

‘Pesu pesemine ei ole kunst!’ (‘Doing the laundry is not art!’). Two women are talking at an exhibition in which the artist is present and drawing on the walls of the gallery. It is a performative exhibition, and the artist comes each day to draw a bit more until the walls are covered with layers upon layers of images. As the days pass, the drawings become more and more confused. Through the middle of the room there are clotheslines with laundry. These clothes, bed linen, towels and other miscellaneous items hanging out to dry are the subject of her drawings. Using charcoal, a dirty medium, she imagines herself as a mother who is tired of the day-in, day-out routine of housework. She asks herself what would happen if she allowed herself to draw on the walls, as she has seen her young child do.

This artist was me, and I often wonder what this woman meant when she said that laundry is not art. Was she implying that doing laundry requires no skill and that anyone can do it? Or did she mean that art and laundry should not be combined? Or is it that laundry is not a worthy subject for art? Or that this exhibition, with laundry hanging in the centre of the room, is not an exhibition of art? I will never know. However, I do know that the words ‘ei ole’ (‘is not’) drew a clear line.

According to Maurice Merleau-Ponty the body, together with perception, is the foundation for understanding and engaging with the world. He describes the body as being held in a circle within which it moves and sees itself; physical engagement with the world leads to cognition and understanding.1 John Berger also talks of a circle when he writes, ‘We never look at just one thing: we are always looking at the relationship between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving, continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to us as we are’.2 In my case, probably because sculpture and installation have been an important part of my art practice, I imagine my body inside a three-dimensional sphere. Within this flexible and transparent sphere, I move, touch, see, sense, feel, hear, and explore what surrounds me. I am at the centre of it. I make the artworks, perform the performances, carry out everyday tasks, and observe and document myself in these various roles. When asked why she wrote her autobiography, Simone de Beauvoir replied, ‘if any individual [...] reveals himself honestly, everyone, more or less, becomes involved. It is impossible [...] to shed light on his own life without at some point illuminating the lives of others’.3 My hope is that if I am doing something with an enquiring mind that interests me, it will also be interesting and relevant to others.

In addition to this phenomenological and autoethnographic approach, I also rely on the notions of bricolage and the bricoleuse in both the theoretical, as well as the practical aspects of art-making. Working as bricoleuse, my research takes the form of bricolage in a somewhat chaotic combination of multi-disciplinary art that includes drawing, performance and video, and installation and sculpture made using a range of diverse materials and techniques, as well as field notes, diary entries, creative and more formal types of writing.

1 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ‘Eye and mind’, in The primacy of perception: And other essays on phenomenological psychology, the philosophy of art, history and politics, (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1964), p. 125.

2 John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: BBC and Penguin Books, 1972), p. 9.

3 Simone de Beauvoir, The Prime of Life (London: Penguin Books, 1979 [1960]), p. 8.

Embodied experiences are an important part of this research, and it is particularly through Thea’s performances and Olive’s work in and out of the studio that this is explored. In his book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, Haruki Murakami writes: ‘I’m the kind of person who has to experience something physically, actually touch something, before I have a clear sense of it. No matter what it is, unless I see it with my own eyes I’m not convinced’.36 I am the same. I can read about how to saw a piece of wood or watch someone else, but I will not ‘know’ it until I do it myself. Sarah Pink, sociologist and scholar of the everyday, encourages multisensory experiences, as well as embodiment and tacit and unspoken ways of knowing, as a methodology for understanding and communicating everyday life. Pink claims that to understand the everyday, which we are necessarily a part of, ‘we need to comprehend it from within’.37 In her own research, she takes an embodied approach in which aesthetics – sight, sound, feel, and smell – the flows of people and things, their stories, biographies, as well as her own role as the researcher, are all incorporated.38

36 Haruki Murakami, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (New York: Knopf, 2008), p. 25.

37 Sarah Pink, Situating everyday life: Practices and places (London: Sage, 2012), p. 13.

38 Pink, p. 33.

My own personal diaries about art-making and cleaning, videos of my cleaning performances, the art objects I make, documentation through video and photography, setting up and presenting my work and research, talking about it, exhibitions of other artist’s work that I have seen (as well as smelled, touched, and heard), as well as exhibition catalogues and the myriad of instructive videos on YouTube are all references and sources for this research. I need to remind myself about art whenever I am seduced by writers, anthropologists, sociologists, philosophers, art theorists, or anyone whose ideas are expressed as text and can easily be accessed and re-read. I believe it is important not only to look at art, but also to sense, hear, smell, and, if possible, touch it; to be with the art, as well as to hear and read what artists have to say.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles and Annette Messager are two relevant artists. The first is from New York, and her service-oriented practice focuses on cleaning and maintenance. She boldly combines art with life by highlighting the underappreciated work of New York sanitation workers through performance and documentary. Like her, I try to combine art and life; however, unlike Laderman Ukeles, my work has an absurdist element to it, and I do not always clean ‘for real’. Sweeping the scrubby outer suburban wasteland in Veerenni, Tallinn (2016) and The Mourning Sweeper at Rookwood Cemetery, Sydney (2018), for example, were not genuine cleaning because neither place needed to be cleaned or swept, at least not with a broom. What I did was pointless, whereas Laderman Ukeles really did scrub the pavement and rake leaves on a college campus and wash the steps of the Wadsworth Atheneum, just as Joseph Beuys did really clean the square after the May Day protests in Berlin in 1972. Of course, Olive also knows about real cleaning.

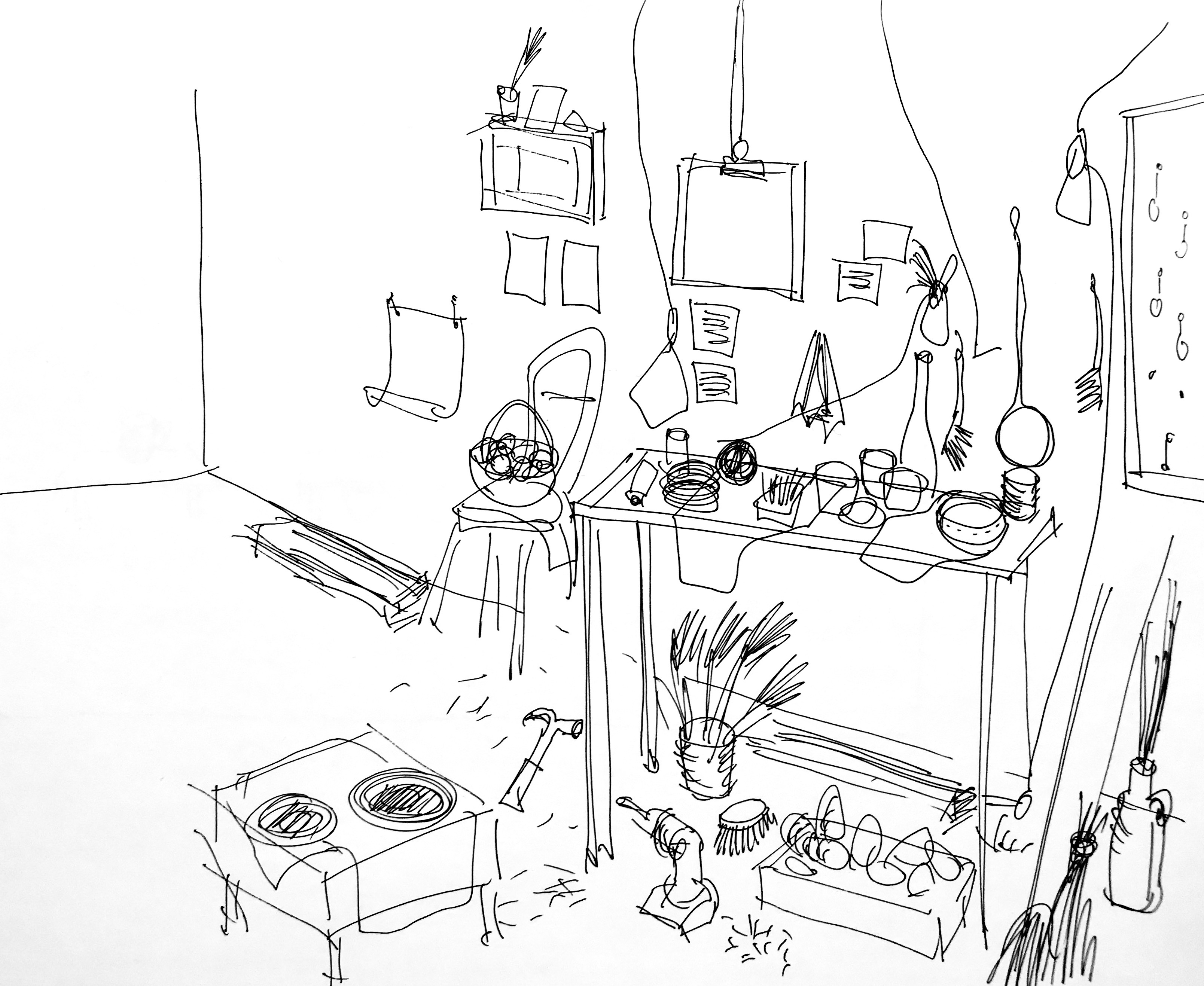

I am still in the workshop, finishing up for the day. I like it here. There is always something to do. But, when I look at the workbench, I’m reminded of Beuys cleaning up after the excitement of the protests, and Laderman Ukeles in her 1969 Manifesto! Maintenance Art – Proposal for an exhibition ‘Care’, when she asks, ‘after the revolution, who's going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?’42

And I need to tidy up this workshop some time.

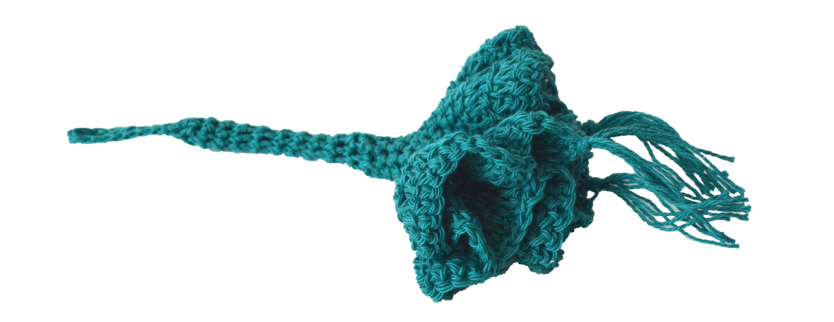

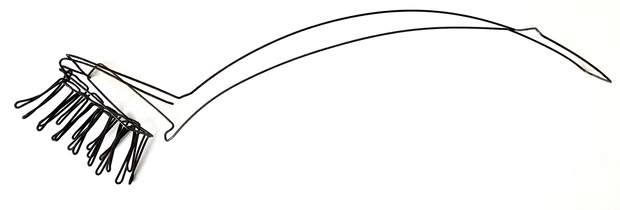

Annette Messager is a self-proclaimed bricoleuse, who blurs the lines between art and everyday life and embraces ambiguity as she plays with the various functions within her home and studio, as well as her roles as artist, collector, trickster, handy-woman, and practical housewife.43 Unlike Messager, however, my work delves deeper into the realm of everyday practical objects that can be used to investigate everyday tasks. For example, Olive’s homemade, handmade tools may not always work well, but Thea perseveres because they were made for her. Using an unusual or ridiculously inefficient tool can direct attention to the bodily experience of cleaning and qualities of dirt in a way that a conventional brush or broom might not. Furthermore, Olive’s handmade practical cleaning tools are also art and can occupy both roles: the quotidian as well as art objects in an exhibition.

I recently watched a lecture on YouTube by the musician, visual artist, and theorist, Brian Eno, titled ‘What is art actually for?’.44 According to Eno, science is interested in this world, whereas art wants to know about other worlds, and therefore, ‘What if? questions [...] are at the centre of [...] all art behaviour’. Artists ask, ‘What if a world like this existed’, and ‘What does it mean when I do that?’, and they say ‘Aah, things can be like that’.

What if…?

This is an open-ended question. Working and researching as an artist means I do not always know why I am doing something. I do not necessarily know why I am making this brush, knitting this cloth, crocheting this round thing, or making this film. What is it for? Why is it important? Is it important? Does it need to be important? And what does important mean anyway?

Contemporary artists engage with the everyday in a variety of ways. They may simply make things visible, or find something interesting and then show us, or they may make the ordinary extraordinary, reveal the overlooked, give voice to those who do not have a voice, or endeavour to effect change. Artists show us things – things that they find interesting. They don’t need to solve problems or come up with answers or define anything. Stephen Johnstone, editor of the MIT publication The Everyday, a compilation of texts by various people including artists, reveals the myriad ways that contemporary artists engage with the everyday and recognises the everyday as a complex contradiction where the alien and the familiar overlap. Thus, any study of the everyday demands ‘an interdisciplinary openness, a willingness to blur creatively the traditional research methods and protocols of disciplines such as philosophy, anthropology and sociology. Perhaps these contradictions and qualifications that characterise the everyday make it seductive territory for those artists who intuitively value the qualities of ambiguity and indeterminacy in their own right’.45 It is these contradictions and ambiguities that make everything so interesting. Rather than attempting to make the world a better place, it is possible, as Hal Foster suggests, to ‘take a bad thing and make it worse’.46 So, instead of cleaning, I could make things dirty.

Olive expresses the difficulty in defining and pinpointing the differences between art and life in the following way:

The squeegee is drying now. The sealer will make it waterproof so Thea can actually use it for washing windows, if she wants to, and it will therefore fulfil its dual role as art and non-art. When I look at the newly painted squeegee, I wonder what it is that I have done? Have I really taken this ordinary supermarket-bought squeegee out of the mundane everyday into a different place – into the world of art? Have I even made an art object? (I don’t want to complicate these questions unnecessarily, but I also wonder if the art is not only contained in the squeegee as an object, but maybe the whole process is the art.) Maybe if I claim that it is art, then it will be. Maybe art is the product of intention, much like Laderman Ukeles’ idea that her acts of cleaning on the street and in the gallery would be art. If this squeegee that I have transformed is art, at which point did it make the transition from non-art to art? Was there a moment of specialness? The story started in a supermarket and moved into a workshop, and I wasn’t even wearing clothes that would suggest ‘artist at work’. All of my actions were quite mundane – shopping, sanding, looking, deciding, and applying paint – and I did not feel as though I was doing anything out of the ordinary. Maybe the moment of transition, if there was one, occurred in the supermarket when I thought to myself maybe ‘Thea needs one’?

This barrage of questions that Olive asks while working suggests that the line, if it exists at all, is moving. I recently became familiar with Rosi Braidotti’s nomadic subject – a theory inspired by nomadic people and cultures, and a way of thinking that questions and defies fixed conventions and established approaches.47 It encourages a flexible and fluid way of thinking that moves from ‘one set of experiences to another [with a] quality of interconnectedness’.48 In the way that Monzaemon’s 'slender margin' cuts through binary thinking, Braidotti’s approach cuts through and across established categories. The line between art and life, like a nomad, is constantly moving, in transit, and thus the perspective is constantly changing – nothing is fixed for long. ‘The nomad’s relationship to the earth is one of transitory attachment and cyclical frequentation’, writes Braidotti.49

42 Mierle Laderman Ukeles, ‘Manifesto! Maintenance Art’, in Boredom: Documents of Contemporary Art, ed. by Tom McDonough (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1995), p. 130.

43 Natasha Leoff, ‘Interview with Annette Messager’, in Journal of Contemporary Art, (undated) <http://www.jca-online.com/messager.html> [Accessed 5 June 2020].

44 Brian Eno, ‘What is art actually for?’ 2012 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIVfwDJ-kDk> [Accessed 8 March 2020].

45 Stephen Johnstone, (ed.) ‘Introduction: Recent Art and the Everyday’, in The Everyday: Documents of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2008), p. 15.

46 Hal Foster, ‘Culture Now: Hal Foster’, 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Esm21k-zW_w&t=1304s> [Accessed 15 March 2020].

47 Rosi Braidotti, Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

48 Braidotti, p. 5.

49 Braidotti, p. 25.

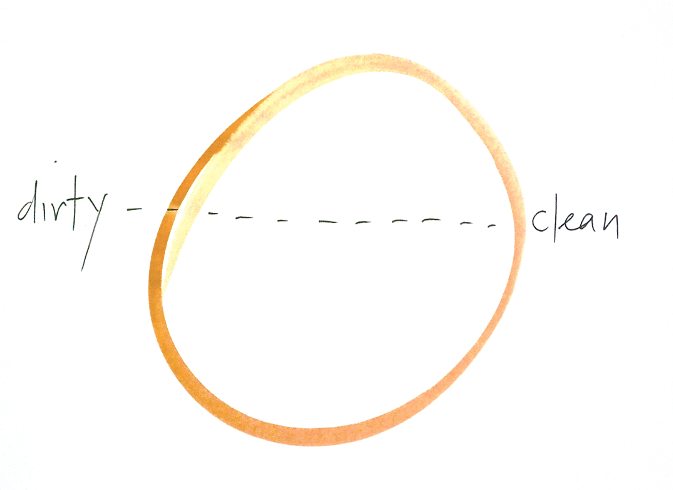

I drew another diagram. This time, the words dirty and clean were joined by a dotted line rather than separated. I realised that the space or time between these two was filled with movement, movement that makes things dirty and movement that cleans. It became clear that one way I could investigate not only the concepts of dirty and clean, but also the line between art and everyday life, was through action, so I started to perform sweeping as art. This was new territory for me because, aside from a few exhibitions where I was present, I had never performed in public and did not consider myself a performance artist (I am still not sure I do, even now).

Thea took part in an exhibition with a series of cleaning performances. Until now, her performances had always started out as precisely that, performances in which she ‘played’ at cleaning, and even though she had discovered a moment when the ‘play’ inadvertently became ‘real’ sweeping or mopping, the impetus from the start had never been to really clean, not properly. She intended to take a different approach this time and decided that the first performance would be to sweep and mop the gallery floor before the opening, something one of the paid cleaners always did. The cleaning company agreed that Thea would take the place of the ‘real’ cleaner.

As she prepared Thea found herself asking a string of questions. What exactly does the real cleaner do? Is the cleaner the same every time? What part of the room does she start in? What does she wear, and what equipment does she use? She asked various people but discovered that neither the gallery manager nor curators could give an answer. It is something we tend not to notice. She did discover that the cleaner sweeps with a rubber squeegee, which helps to keep dust from flying around. She recalled having seen a long-handled squeegee hanging on the wall in the gallery storeroom and was keen to try it.

The day before the opening Thea went to do some practice cleaning to see how long it would take. The plan was to start cleaning before people arrived and finish during the opening. As well as sweeping she planned to mop the floor, and needed to make sure that the main thoroughfares, such as the entrance way, were dry by the time people arrived.

An hour before the opening Thea walked into the toilets to fill her blue bucket. She walked past a cleaner’s trolley with all its cleaning equipment, a special place for a plastic rubbish bag, bottles of cleaning fluid, and cloths. ‘I hope I don’t run into her.’ But of course, she did. ‘Oh no!’ she thought when she saw the real cleaner in the toilets, cleaning the long basin that ran the full length of the wall. She was the last person Thea wanted to meet. Dressed in her colourful costume she already felt a little self-conscious walking from the gallery to the toilets. The basin had a long mirror that also ran the full length of the wall. They were the only people in there. The real cleaner noticed her both in the mirror as well as when she turned to see Thea place her blue bucket into the basin to fill it. The real cleaner’s up and down glance at her outfit was enough to convince Thea that she knew exactly what she was doing. Thea felt as if she had been caught out.

Earlier, before Thea had her costume on, the real cleaner had come to the gallery door. Thea could tell by her body language – she was smiling and shaking her head – that she knew she did not have to clean, not tonight, not this time, even though there was an opening in an hour. She had probably come to make sure that this was correct.

While Thea waited for her blue bucket to fill up, the real cleaner turned and spoke to her. Thea immediately protested that she did not speak Russian, until she realised that she was, in fact, speaking Estonian, albeit with an accent. Thea felt embarrassed and regretted that she had not recognised this right away. The real cleaner offered to assist her in cleaning the gallery floor. Thea was surprised and replied with a hasty, ‘Ei, ei! Ma teen. See on kunst’ (‘No, no! I will do it. It’s art!’), and immediately regretted using the word ‘art’; she had drawn an unnecessary line. Thea was touched that the real cleaner offered to help but this only contributed to her awkwardness. She was playing at something, whereas the real cleaner was genuine. It was not until later that she wondered if perhaps it was not pure generosity, but fear for her job, fear of getting in trouble with her boss for not cleaning when she should have. This was not the first time Thea realised she was flirting with cleaning, that by performing cleaning as art, she might be stepping on someone’s toes. She did not mean to mock real cleaners and their work, but her performances, costumes, and equipment could be interpreted as such by those for whom it is real work. Thea was ashamed and embarrassed, and she wanted to leave as soon as possible.

The blue bucket was now sufficiently full, and Thea lifted it out of the basin and walked back to the gallery, taking care not to slosh it.

And the rubber squeegee was very effective, but it did not work as well in the corners as a bristled broom. And the way it swivelled was also very pleasant. As a performance it felt good. To be cleaning for real meant she had a reason for being there and a logic to what she was doing.

The Cleaner Cleans Again, performance as part of "Maintenance is a Drag (It takes all the Fucking Time)", EKA Gallery, 2020, Estonian Academy of Arts, Tallinn, photo Rolf Hughes

…equipped with a line, a circle and accompanied by three friends…

There are four of us working on this project. I am real, and the other three are imaginary. My imaginary friends are Thea Koristaja, Olive Puuvill, and Artist Researcher (who still doesn’t have a name). Thea was the first to appear on the scene. Olive and Artist Researcher soon followed. Their presence made it easier to distinguish between the various parts of the research. They also provided me with a sense of companionship and shared responsibility in what felt like a lonely pursuit at the time. I quickly discovered that not only could they help me observe from the inside, revealing embodied experiences of performing and making, but they also gave me distance to observe from the outside, and, most importantly, they gave me the courage to ask seemingly silly or simplistic questions. I hesitate to describe them in detail because I do not want to fall into stereotypes, but Thea does most of the performing and cleaning, Olive does most of the making, and Artist Researcher most of the observing. She is also the one who tries to tie everything together and communicate our work. And me, well my job is to accompany and work with them. Our responsibilities overlap; Olive may go to the library and then return home to do laundry or vacuum the floor. Sometimes Thea and Artist Researcher are together making something in the studio, and at other times we are all together in a café or walking down the street. The thing that unites us and remains a constant is that we are all artists; we do our work and research using the methods, tools, and attitudes of an artist.

Swish–swish–swish, the sound of my broom as I sweep with strong strokes passing from left to right and back again on the dusty, sandy earth. The broom is heavy, so I switch hands regularly. The handle is smooth and pleasant to hold. As I sweep, I feel like I am doing a dance. The weight of the broom as I swing it or push it sets up a momentum that my body easily follows. The ‘dance’ stops when I try to brush a stone away, but it won’t move. With a little perseverance, and after a few more goes and feeling slightly annoyed, I manage to shift it and resume my sweeping.

This is the first time I am using this broom and its bright blue bristles are becoming dirty brown. It’s a shame. The dust flies left and right and, when the wind blows, my feet and legs pass through a cloud of dirty dust. I watch the rising fold of sandy earth as it moves ahead of my broom. I look back to see the cleared line that I have swept and feel satisfied. But why should this be satisfying? This sweeping I am doing is quite pointless...no one asked me to do it. There is no reason for sweeping this dirt. I am like Guazi and his mouthfuls of dirt...just taking it from one place to the next.

As I see the pile of dirt accumulating in front of my broom, I think about what I am doing; what are any of us are doing when we clean? I’m moving dirt from one place to another; to quote the catalogue text accompanying the exhibition ‘Heavy Artillery’ showing work by artist Liu Chengrui (aka Guazi, b.1983) at White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney in 2016, ‘we only move it around’.5 In his video ‘Guazi moves Earth’ (2008), he carries dirt in his mouth over a distance of about 50 metres only to return and take another mouthful. Repeating this action over many days, he crawls on his belly, wriggling like a snake; his effort is obvious and brings into sharp focus the apparent pointlessness of his task. As he squirms his way back and forth, his own body gets dirty. The catalogue text goes on to say, ‘Dirt is dirty. Handle it, and we become dirty too. We can ignore it or hide it, but its dirtiness remains. And when we clean it away, we only move it around’.6

Sometimes it feels like a game. One could say that Thea is merely playing at cleaning. However, games can also be serious. Allan Kaprow writes about ‘happenings’, a term he coined in 1959 to describe a type of art event or situation that explored and blurred the line between art and daily life.7 His writing includes detailed instructions, similar to a handbook. In his essay ‘The Happenings are Dead: Long Live the Happenings!' even refers to these instructions as the ‘rules of the game’, and the first rule, for example, begins with the instruction that ‘The line between the happening and daily life should be kept as fluid and perhaps as indistinct as possible’.8 Though his investigations appeared to be playful, they led to insights such as the following from his 1979 essay ‘Performing Life’, in which he explores the idea of daily life as something performed and makes the following observation: ‘When you do life consciously, however, life becomes pretty strange – paying attention changes the thing attended to – so the happenings were not nearly as lifelike as I had supposed they might be’.9 His work produced what he refers to as a ‘new art/life genre’ that reflected ‘equally the artificial aspects of everyday life and the lifelike qualities of created art’.10

So, life can also seem artificial, just as art can be lifelike. I like that.

5 Heavy Artillery exhibition catalogue, (Sydney: White Rabbit Gallery, 2016).

6 Heavy Artillery exhibition catalogue.

7 Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993).

8 Allan Kaprow, ‘The Happenings are Dead: Long Live the Happenings! (1966)’, in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993), p. 59.

9 Allan Kaprow, ‘Performing Life (1979)’, in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993) p. 195.

10 Kaprow, p.195.

Provoked by the conversation between these two women I wanted to learn more about the connections and overlaps, boundaries and lines between contemporary art, art-making, and quotidian aspects of everyday life. This led to my main question, which is whether there is a line between art and life. This apparently simple, even naïve question was quickly followed by a flurry of others. If such a line exists, how do I identify it? What does it look like? What is it like? Is it clearly marked and visible? Is it fuzzy or blurry? Is it straight or wiggly? Can I cross it? If yes, how, and what will happen if I do? How can I show that I have done so? How will anyone know? Conversely, if there isn’t a line, why do we act as if there is one?

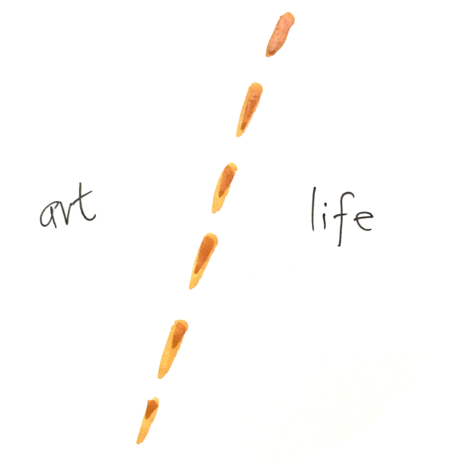

As I began the process of puzzling it all out, I wrote the words art and life on a piece of paper and drew a dotted line between them. I imagined this line as something to be stepped over, like a line drawn on the ground. For a while, it was interesting, but it suggested that we live in a two-dimensional world, and the line soon began to look more like an invisible wall or barrier in space that I imagined I was breaking through. As my research progressed, the way I was looking at the line began to change and instead of thinking about crossing it, I realised that some of the time, I was, in fact, walking along it, a bit like a balancing act. But I am getting ahead of myself. Let me introduce the circle.

My first explorations into the line between art and life was through the practice and performance of cleaning. For I long time, I have explored the things that are closest – the home, the domestic, the ordinary, you might say the overlooked, the things that are so close we cannot see them, but the exhibition with the two women talking was the first time I made a direct connection between cleaning and art. As a mother with young children, I was doing my best to keep up with laundry and maintain a clean home. The exhibition was inspired by some small drawings surreptitiously scribbled on the wall by my children. I marvelled at their freedom to do so, and tired of being the responsible adult concerned with laundry, I, too, wanted to draw on walls. So, for two weeks I drew with charcoal on the white walls of the gallery. I delighted in the blackness of my hands, the ever-thickening line of charcoal dust on the floor, and the darkening layering of drawings on the walls. I did not think about cleaning because I expected the charcoal to come off easily. As it turned out, even after a full day of exhausting washing, the grey ghosts of my drawings remained visible, and the walls needed to be painted before the next exhibition. It was in the context of the tail end of this exhibition and separated from everyday life, that the physical effort involved in cleaning and the idea that at the end of the day someone must clean up the mess, came into sharp focus.

Cleaning is something we all do, in all parts of society, in all geographical locations, and in all periods of time; it unites us. The cleaning I wanted to focus on was the unpaid cleaning that we all do, such as vacuuming the floor, brushing our teeth, or, at the very least, wiping the crumbs from our mouth. It is one of the most mundane aspects of life and regarded as one of the lowest expressions of the everyday. By incorporating cleaning into my art practice, I wanted to not only draw attention to something close yet overlooked, but also to connect the mundane with the sublime. While contemporary art does not always enjoy an elevated position, it is still regarded as something special, something outside the ordinary. And, to be honest, there was a certain satisfaction in combining not only art and cleaning, but also research, because suddenly, whenever I vacuumed the floor or wiped the table, I was also doing doctoral research.

The everyday is what we do on a regular, maybe daily, basis. It is the ‘un-special’ moments in our lives, the things we do not give much thought to, like eating breakfast, catching a bus, or turning on the tap. As an artist, I see no difficulty with using art to research the everyday, but others do. Yuriko Saito, who works in the field of everyday aesthetics, has a problem with what she calls ‘art-centred aesthetics’ as a way of understanding the everyday, and claims that the tension between art and the everyday poses a ‘serious challenge’ for anyone attempting to break down what see sees as the barrier between art and life.39 She asks if it is possible to break down this barrier, or if ‘art [is] forever stuck within the inescapable boundary set by the artworld?’40 This appears to be rigid thinking, one that does not value fluidity, flexibility, or fuzziness, and I am not sure it is the artworld that is drawing the lines. Furthermore, the everyday is not a fixed thing; what is ordinary for one person may be extraordinary for another. Once we study something that was previously overlooked, it is no longer overlooked and may no longer be ordinary. For artists, art and art-making is likely a part of their everyday and as Epp Annus rightly points out, ‘writing and thinking about everyday experience, as well as painting, photographing or filming it, may very well be the most quotidian activity for scholars, novelists, painters and filmmakers’.41 I am confident that it is not only possible to use art to research, but that it can also be uniquely revealing in unexpected ways. Based on my experience of performing cleaning as art, I believe that by framing the research in an art context, the subject, with all its characteristics, qualities, contrasts, and similarities is made more visible. Performing the everyday through art can be a way of stepping outside the familiar to be able to see more clearly. Being ‘in’ the research, whether it is in a sweeping performance in front of a video camera or by drawing the movements the hand makes as it sweeps, mops, or vacuums, heightens awareness of oneself within an event, situation, or space.

Thea can tell us more.

Let me tell you about being ‘in’ and ‘out’ of art and crossing that line. There are two occasions when I felt like I was very clearly crossing a line. The first was when I was filming myself as I swept with one of my brooms, and the other when I used a handmade art-object cloth (that had been shown in an exhibition – so surely, that must make it art) to wash the dishes.

I was filming on my own and had to be both performer and filmmaker and was consequently walking back and forth between the performance area and the camera. After repeating these actions many times, I became distinctly aware of there being a time when I was just walking, and then a moment when I entered the ‘art’ and I believed myself to be in shot and consequently ‘in’ the art, fulfilling my role as performer focused on sweeping the footpath. That moment was a split second, yet I felt like I was crossing a distinct barrier between ‘in’ and ‘out’. When I finished the sweeping, which ended when I believed myself to be out of shot, I crossed back through the invisible yet perceivable barrier, and my thoughts switched from performing to my role as filmmaker, wondering whether the camera was angled correctly, how much longer the battery would last, and how loud the incidental noises would be in my film. These split-second moments are caught on film, but there is nothing in my facial expression or body language that indicates the switch in roles, or that in one moment I am ‘in’ art and then ‘out’ of it.

The other time was when I was washing the dishes using a hand-knitted cloth that had never been used or even wetted. I recall that, as I dipped it into the water, I felt I was doing something that I shouldn’t (to be honest, I had a gleeful sense of doing something ‘naughty’), probably because art objects are considered special, usually non-functional, and definitely not be used for something as mundane as washing dishes. Of course, it isn’t only art objects that are perceived as special and not to be used for functional everyday use, because handicraft items and even everyday, shop-bought tablecloths and towels seems to retain their specialness by not being used; much like a clean sheet of paper, they continue to have potential as long as they remain unused.

While Thea was thinking about the line between art and life, she noticed another line being crossed, the line between clean and dirty. It was not just that the new handmade cloth, posing as art was taking on a new role, but there was also a chance that it would get dirty, or at the very least become misshapen if it got wet (and therefore not look new anymore). The art versus non-art line relies heavily on the context where the object sits and how it is handled, whereas the dirt versus clean line is more obvious because we can see the dirt. I am thinking here of the moments before Thea placed her new, clean, handmade mop onto the dusty ground at Veerenni.

The white cotton strings of the mop head and the water in my blue bucket are clean. The water looks clean enough to drink and the cotton strings are white and soft, so it would not be odd to caress or smooth them across my cheek. Once the wet mop touches the dusty, gravelly soil of the unused dirt road, it becomes dirty, very dirty. And within 10 minutes of mopping, the water in the bucket is no longer water, but thick mud.

39 Yuriko Saito, Everyday Aesthetics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 251.

40 Saito p. 250.

41 Epp Annus, ‘Introduction: Thinking and Discussing the Everyday Experience’ in Experiencing the Everyday, (eds) Carsten Friberg and Raine Vasquez, (Copenhagen: NSU Press & Nordisk Sommaruniverstet, 2017). p. 7.

It started with a line and a circle. There was laundry. There was art. And there was movement. And they all became entwined.

Much of what I have explored is based on my original idea, which is represented by the dotted line separating art and life. I tested it by entering and exiting art when I filmed myself performing sweeping. When I washed the dishes with the knitted dishcloth, it became an invisible curtain or barrier that had to be passed through. As the research progressed, the line began to feel like a knife edge, similar to the knife edge in the following walk to the station.

She’s almost there. She’s been walking for 15 minutes or so, striding along, and her walking has settled into a rhythm. The concrete footpath in front of her repeats its squares of paving. The tips of her black Redback boots keep entering her field of vision. The path stretches out straight before her and a thought enters her other thoughts, which have also been striding along across and along the dips and turns of where she has already walked. This new idea is that as an artist doing artistic research, she is treading a thin line between intelligence and lunacy. On the one side is the need to read, understand, explain, communicate clearly, and on the other is the crazy, mixed up, sometimes nonsensical, independent world where 'anything goes', where nothing needs to be explained, and maybe where nothing should be explained. She’s on her way to the university, wondering if she will tell the others about walking along this knife edge between sanity and insanity.

It shouldn’t be difficult to tell them. The university is in a former mental asylum.

Throughout this research there were moments when the line appeared to be well-defined, and others when the distinctions became fuzzy. When I first read Monzaemon’s concept of art inhabiting the ‘slender margin between the real and the unreal’, the beautiful complexity of what I was looking at really started to take hold.50 This slender margin, not on one side or the other, but between, indicated that there were other ways of looking at the question. Maybe my ambiguous hybrid objects that are both familiar and unfamiliar, as well as the cleaning performances that are both real and play, inhabit that slender space. As I continued working, performing and making objects that balance on the borders, the complexities and ambiguities in the relationship between art and life became more obvious, for example, when Artist Researcher describes how she is trying to work but life keeps intervening, and her boundary crossing experience as she walked along the beach. And, even though I had asked whether there is a line between art and life, it has become clear that my intention had never been to define the line and decide what lies on either side of it. I preferred to blur and confuse the borders, to muddy the waters between tools and ornaments, art objects, and functional objects, playing or doing something for real, the ordinary and the extraordinary, the overlooked and noticed, in order to debunk the concept of a line that separates and divides. The line became fluid and flexible, tangible and intangible, visible and invisible, and instead of separating, it started to traverse and link, tie and bundle together, creating new spaces and revealing new ways of seeing.

50 Susan Sontag, ‘A Note on Bunraku’ in Where the Stress Falls. (London: Vintage, 2003). p. 138.

I could write an interview with Cleaning; no, today I need to do that translating; I could do with a coffee; my laptop is so slow today; I’ll do a restart; beep! beep! beep!; the washing machine is finished; I’ll embroider a bit while I wait for the computer to reboot; oh, I have to remember to do a backup; what did Rancière say about equality and practicing it? Or was it Jacotot who said that?; knock! knock!; someone at the door offering to do tree lopping, politely took his business card; I embroider the word ‘tolm’ (dust); beep! beep! beep!; aah, yes, the washing machine; hang washing on line; what happened to that coffee?; oh, yes, I need to paint those frames; back to translating; but what about my own work?

My mind reels when I realise what I am taking on, and I question whether I need to define art because that is what this increasingly sounds like. Questions run through my mind. What is art for? Does it need to be for anything? How do I define non-art, or even the everyday? For a moment, I thought I’d let Olive grapple with these questions, but she is too busy. She is engrossed with the work of making, selecting, choosing, affecting, changing, and I think for her, these questions are irrelevant. Whereas I am daunted by it and my mind seizes up when I consider writing about it. It is mostly when I am away from my laptop and have no pen or paper handy, especially when I am out walking, that I am able to compose a very clear discussion about the relationships between art and life and its complexities, starting with my original ideas about the line between art and everyday life, through all the different fuzzy variations I have imagined along the way.

Kaprow describes non-art as ‘whatever has not yet been accepted as art but has caught an artist’s attention with that possibility in mind', but the problem with non-art is that as its lifespan is fleeting because as soon as ‘any such example is offered publicly, it automatically becomes a type of art’.34 In the same way that as soon as you look at something, it no longer overlooked. Perhaps the artist is a magician, and everything they touch turns into art, much like Midas who turned everything to gold whether he wanted to or not. The artist only needs to think of something as art, and voilà! it is art! As soon as I point my gaze, my camera, or my pencil at something, the thing turns into art. But, before I become too excited about this idea, Kaprow points out that some non-art situations, such as the broadcast conversation between astronauts on Apollo 11 and the ground crew in Houston, are often more interesting that artist interpretations of these events.35 As an artist it is sobering to be reminded that not everything that is art is necessarily interesting.

34 Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (London: University of California Press, 1993), p. 98.

35 Kaprow pp. 97–98.

Olive Puuvill

She makes things. She works like a bricoleuse, making the outfits and cleaning equipment, but she also edits the videos, draws, does the sawing and sewing, knitting and hammering, and builds the tables and attaches the hinges. Bricoleur, the masculine form of the term, is largely and historically associated with men and ‘men’s work’, but as a woman, it is obvious that we should use bricoleuse, the feminine form.11 However, Olive Puuvill does not want to distinguish between women’s and men’s work, and in the spirit of a bricoleuse, she sources techniques and materials from the sewing basket, kitchen, garage, workshop, or even the side of the road; she also claims the right to use the tools, techniques, and workspaces commonly associated with men, if necessary.

Hello, I’m in the workshop with a notebook open on the bench next to me so I can write down any thoughts I have while I’m working. I admit this isn’t always successful. Usually, I just get too involved in what I am doing. But before I start work, maybe I should tell you more about the bricoleuse.

A bricoleuse is someone who invents, improvises, and ‘makes do’ using tools and everyday materials that happen to be ‘close at hand’. Claude Lévi-Strauss describes them as someone who ‘uses devious means compared with those of a craftsman’.12 Devious, in this context, means ‘to deviate’ in the way that a ball might bounce off in an unexpected direction; many artists, especially sculptors and installation artists, can be described as bricoleuses.13 This is an apt image because artists often use ‘off the wall’ ways of working and solving problems. Lévi-Strauss also says that the bricoleuse is someone who works with their hands (he insists on using the masculine form, but I guess he didn’t know I was going to quote him).

I work with my hands.

Lévi-Strauss also distinguishes between the bricoleuse and the engineer. ‘The bricoleur is adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks; but, unlike the engineer, he does not subordinate each of them to the availability of raw materials and tools conceived and procured for the purpose of the project. His universe of instruments is closed and the rules of his game are always to make do with “whatever is at hand”’.14 Their work is not defined by their projects or their tools. Both materials and tools ‘are collected and retained on the principle that they may always come in handy’,15 and the bricoleuse does not need to have all the equipment or expertise but just enough. The tools and skills for one task can be used for another similar task. But the line I especially like in Lévi-Strauss’ description is ‘Consider him [her] at work and excited by his [her] project’.16 As a child, and even now sometimes as an adult, I get excited about something I plan to make. My skills and haste often let me down, but I’ve learned not to let this bother me and I just keep on going. I sculpt and draw. I add and remove. I scrub and wipe. I install and saw and hammer and crochet, knit and embroider. I photograph and film. I use whatever materials are at hand. I use whatever techniques and equipment are available.

Olive is not only a bricoleuse, but also an artist. She is not always cognisant of what she is making and for what purpose or with what intention. She gets excited by her work, and also by Russian formalist writer, critic, and literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky’s idea that art is about making things strange or unfamiliar, especially because her work draws on the everyday and therefore familiar, not only for inspiration but also for materials and techniques. Shklovsky writes in his 1917 essay ‘Art as Device’ about how art can cause us to see things we might not notice otherwise simply because they are familiar.17 As perception ‘becomes habitual, it also becomes automatic’.18 Our heightened awareness when we experience something for the first time is dulled by what he refers to as a process of automatisation in which things are replaced by symbols and ‘objects are grasped spatially, in the blink of an eye. We do not see them, we merely recognise them by their primary characteristics’, and ‘under the influence of this generalising perception, the object fades away’.19 He illustrates this point with a quote from Tolstoy’s diary describing how he was cleaning. Tolstoy’s movements were habitual and unconscious, and when he approached the sofa, he could not remember if he had already dusted it. Because he couldn’t remember, it was the same as if he had not. Only if someone else had been there watching could they confirm whether he had or had not. Tolstoy continues this observation and suggests that ‘if the complex life of many people takes place entirely on the level of the unconscious, then it’s as if this life had never been’.20

Shklovsky continues, ‘And so, in order to return to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make a stone stony, man has been given the tool of art’.21 To make us feel things, to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are recognised, art uses different tactics to make objects unfamiliar by what he calls estrangement, or as it is also translated “defamiliarisation” and “making strange”,22 which aims to interrupt the smooth flow of automatised perception and allow us to see things, as if for the first time. Perception takes more time and is, in Shklovsky’s words, ‘laborious’. The artfulness of the object removes the automatism of perception. It aims to slow you down, to make you stop, and it is the slowness of this perception that achieves the greatest effect, an effect that both Thea and Olive are aiming for.

Olive makes things that teeter on the borders. She aims to blur the lines between art and everyday life with objects and artworks that straddle the distinctions between handicraft and art, functional and non-functional, extraordinary and familiar.

11 Sara L. Wheeler, Researcher as bricoleuse rather than bricoleur: a feminizing corrective research note, (2015). <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283794747_Researcher_as_bricoleuse_rather_than_bricoleur_a_feminizing_corrective_research_note> [Accessed 7 Nov 2018].

12 Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholas, 1966 [1962]), p. 16–17.

13 Jyrki Siukonen, Vasar ja vaikus (Tallinn: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia Kirjastus, 2016 [2015]).

14 Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholas, 1966 [1962]). p. 17.

15 Lévi-Strauss, p. 18.

16 Lévi-Strauss, p. 18.

17 Viktor Shklovsky, ’Art as Device’ in Theory of Prose, trans. by Benjamin Sher (Illinois: Dalkey Archive Press, 1991) [Accessed from https://doubleoperative.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/art-as-device.pdf].

18 Shklovsky, p. 4–5.

19 Shklovsky, p. 5.

20 Shklovsky, p. 5.

21 Shklovsky, p. 6.

22 Ben Ehrenreich, ‘Making Strange: On Victor Shklovsky’, in The Nation, 5 February 2013 [Accessed from https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/making-strange-victor-shklovsky/].

Artist Researcher

She spends her time observing, analysing, and interpreting what the other two are doing. She is tasked with communicating this through her writing, speaking at seminars or conferences, and to people she meets. I like to imagine the others dismissing her by telling her to go to the library or her laptop and not bother them; they are too busy getting on with their work to be interrupted by research questions, other people’s expectations, or how to format footnotes.

art and life, art-making, autoethnography, blurring, bricoleuse, cleaning,

embodied research, everyday, fluidity, lines, the circle