Chris Dave: Thank you so much for coming and checking out us and the music and everyone who’s here. To translator Tell ‘em to think of this experience as a live audio mixtape. So we’ll go through different genres of music. Maybe things people know, things people don’t know, but it’s just a journey. Take the journey with us through this music...

Translator: I already told them…

Isaiah Sharkey:

It is perhaps surprising to the modern listener that the jump from a shuffling melody to Chopin’s ‘Funeral March’ is not a jolting juxtaposition. After all, how could a nineteenth century piece of classical music sit within a jazz quartet’s oeuvre? But this allusion allows us to investigate the syncretic nature of jazz music, a music that amalgamates a vast range of seemingly contrasting influences.

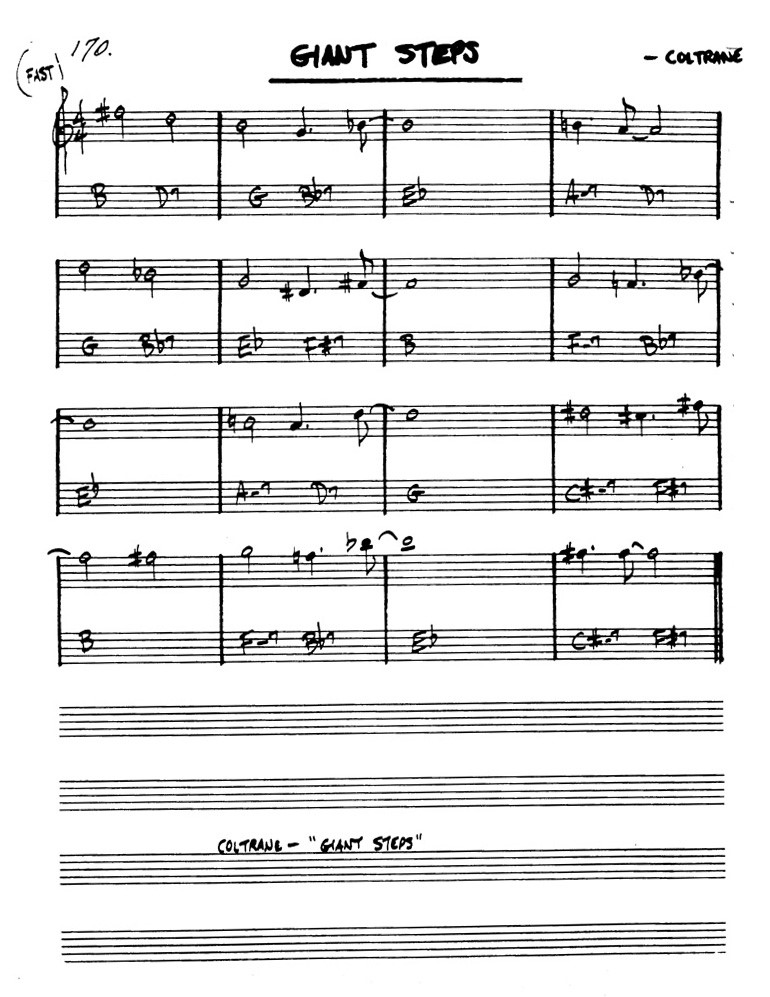

Combining the shared influences and applications of a sonic artefact, inspired by the same piece, The Drumhedz are able to co-opt the cultural and emotional narratives of Coltrane, Pass and Dilla and transform it into a shared event. Dave modernises and contributes to a contemporised, intertextual narrative of ‘Giant Steps’ to create a live musical palimpsest, bridging culturally disparate styles.

This palimpsest is an extension of the contrafact. While contrafacts were used as a means to create new pieces over which to improvise, The Drumhedz acknowledge the ontology of their musical influences in a contrafactum, a new artwork based significantly and adventurously on another. Through these contrafactum, Dave performs and acknowledges his panoply of influences in a single performance, rather than singular influences in single tracks (a contrafact). Highlighting Dilla’s indebtedness to Pass, and Pass’s to Coltrane, Dave intermixes his influences to perform a running history, a process, of the music being performed. One can trace the development of The Drumhedz’ performance within its own idiom and animate sphere of influence. Dave illuminates the theoretical mechanics of Dilla’s art form.

Translator: cont. that, but I will again…

I.S.: cont.

Translator: cont. I think…

I.S.: cont.

C.D.: Ok, tell them: close your eyes…

Translator: Ok… closes eyes

I.S.: cont.

C.D.: No, tell them: close their eyes! And open your ears; open your ears, open your mind: listen to this live take.

Translator: translates… Drumhedz!

I.S./Nick McNack/C.D.: cont. (variations to illustrate rhythmic interplay)

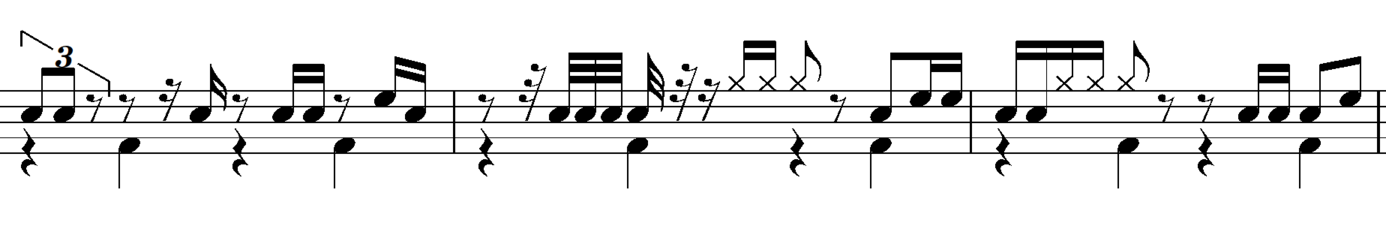

Crucially, Dave does not perceive his playing style to be polyrhythmic. Polyrhythms are always necessarily apophatically defined (defined against what they are not, being the central pulse) and to be polyrhythmic, Dave would have to be playing against a main ‘correct’ pulse. In reality, however, he and The Drumhedz feel multiple pulses simultaneously. Does Dave play in 4/4 with 12/8 interpolations or vice-versa? Or neither? Or something else entirely? Ultimately, the question is irrelevant, since no singular pulse holds authority over the others in order to centralise a definition of Dave’s playing. This allows Dave the freedom to seemingly slip ‘in’ and ‘out’ of ‘time’ freely and play phrases that are analogous to Ornette Coleman’s ‘erasure phrases’. The Drumhedz play polytempic time not as ‘either/or’ but ‘both/and’.

Subsequently, all instruments can influence a real-time development of musical exploration, removing the limitations of an isometric framework entirely. (Nonetheless, looping technology allows them to freely interact – liberated from ‘supporting’ roles – and retain a clear rhythmic backdrop, should they wish. In this case, Sharkey becomes his own interlocutor among the musical dialogue and avoids solipsism.) This egalitarian liberation allows The Drumhedz to play within a nonlinear constant progression between clouds of mood and influence that occupy interdependent pulses. A live collaboration is enabled that is not limited to or restricted by form, feel or pulse, but is free even to settle on a groove for some time should the vibe require.

C.D.:

Isaiah Sharkey - guitar

Nick McNack - bass

Keyon Harold - trumpet

Chris Dave - drums

Chris Dave & The Drumhedz, thank you so much for coming out.

In 2002 the ‘future of jazz’ was hypothesised by critics as complex, genre-less music with a direct interaction with the fan-base. These critics’ theories, however, were predicated by the caveat of ‘the distant future’, suggesting at the cultures of 2027, 2028 and 2032. It seems they underestimated the sheer power and speed of development that new technologies brought to the world. Fundamentally, Dave is already there, embodying this image of the ‘future of jazz’. Dave’s style is still novel, however, and wholly foreign to some. But, with this performance in mind, it is easy to see why - earlier than anticipated - he is ‘totally reinventing’ the drum-set.

Outside of conventional concepts of ‘time’ in popular music, each musician manipulates the organic pulse discretely, allowing the audience a parallax notion of musical momentum. Remaining open to numerous pulses moving autonomously, The Drumhedz could be said to play time diachronically. All ‘pulses’ exist always-already extra-musically, irrespective of the coordinates of performance; only by strictly contextualising one pulse does one become authoritatively ‘correct’ and introduce the possibility of dragging or accelerating. Elasticising the beat is an old practice, but Dave pushes the idea further, removing the regular rhythmic supportmatrix traditionally available to other players, creating a free improvisatory environment.

This challenge to hegemonic cultures of consumption (here: Chopin is ‘classical’ and to be read as such) rails against cultures of commodification. Consciously or not, such practise is analogous to the work of the avant-garde (née free jazz). It is worth remembering that Dave released his only album as a leader gratis, ‘to thank people for the support and then aware other people of why they support us, if they care to know’. If there has been a more direct and personal statement for listeners rather than consumers, I am yet to find it.

Inter- and intratextual music, and the combining of divergent styles or feels, has long been a practise of avant-garde artists. Examples can be found in the transcultural and kaleidoscopic works of numerous performers, who comment on their own pieces, their inspirations and – metatextually – the syncretic narrative of their performances freely and in real time. Liberation Music Orchestra’s eponymous 1969 album, for instance, fuses Spanish folk melodies, circus music and even a sample of Carlos Puente playing ‘Hasta Siempre’ mixed into the live tracks. As Jim Macnie observed, there are precedents for a crafted balance between the purely free and the compellingly written in live musical dialogue.

It is tempting to define this interaction between Sharkey, McNack and Dave (‘Didn’t Exist’) as either heterophony or polyphonic stratification, but neither are really appropriate. It is simultaneously both polyrhythmic and polyphonic stratification, and neither. The interaction is not solely about melodic line, pitch or rhythmic placement, although those aspects are invaluable. There is no hierarchal, stratified opposition of pitches, textures or rhythms, either, for all occupy the same plane of musical influence upon the others. Rather, it is an organic interaction centred with a fluid ‘pulse’ but not fixed ‘time’. All performers interact within a regular and fixed pulse that is not isochronous. The beat-upbeat ratio is unstable in a musical palimpsest, amended as it is written.

The Drumhedz break away from the confines of an isometric pulse and interact around a sonic theme and feel. Dave, far from peripheral in laying the groundwork for the melodic instruments to explore, freely explores the musical landscape with his collaborators. He emphasises different dimensions of a multidimensional sensory experience: McNack, Sharkey and Harrold move spontaneously through the melodic and harmonic planes, and Dave uses his atonal immobility as an advantage, probing rhythmic and textural dimensions. Arguably, Dave’s free playing is more significant than melodic free phrases. Playing against the axiom of drums-as-rhythmic-foundation, Dave places them equally alongside other instruments within the improvisational landscape.

A dichotomy persists. How can we reconcile The Drumhedz free approach with performances that include instantly recognisable tunes? We can here examine Dave’s influences from hip-hop and digital culture more thoroughly, having just heard a rendition of Outkast’s ‘Mainstream’. Without a trace of iconoclastic imperative or effort towards ‘innovation’, Dave plays ‘things [he] like[s]’, conjoining jazz, hip-hop and other styles freely. The performance epitomises Dave’s style. He switches freely between a swinging beat and a groove stylised to mimic the bouncing feel of Dilla’s production (in which an unquantised beat melds disparate parts that fall on, before or behind the beat independently, while maintaining a central pulse – a huge influence on Dave).

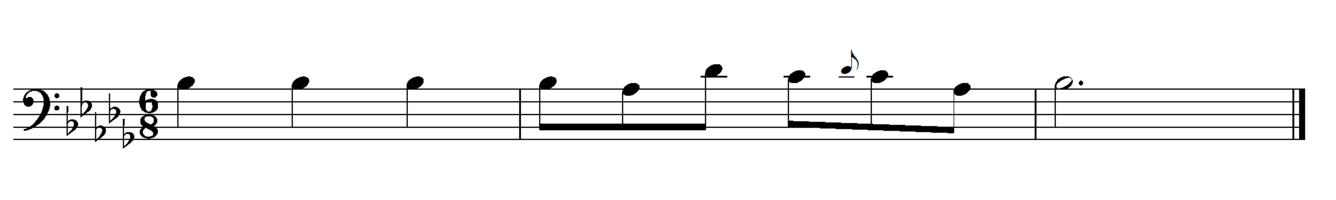

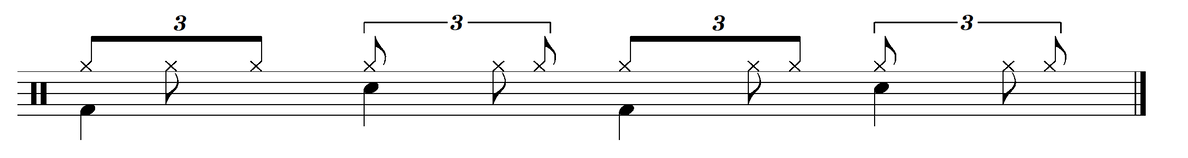

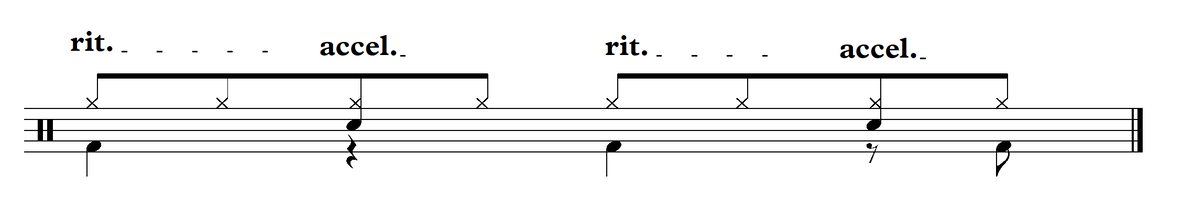

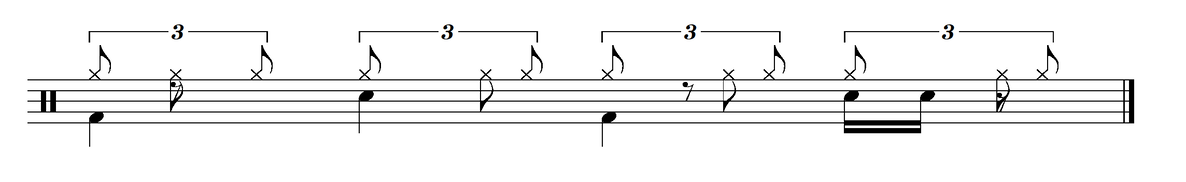

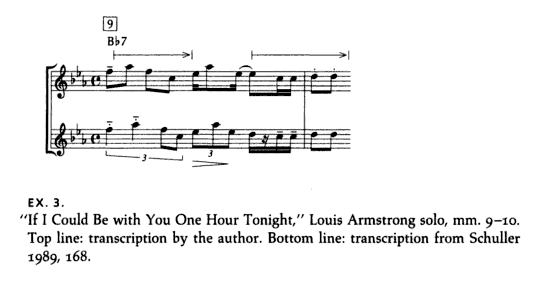

Dave’s variations; one can see between the versions how Dave improvises.

‘Time’ is a floating signifier, rendering The Drumhedz able to rewrite not just the signified but the very presence of the signifier at any moment. Partly, authorship then falls upon the experiencer: to decode this openness and frame it through their own experience.

The consequential ‘bounce’ is mediated through slight (lengthened or shortened, or, equally significant, not-lengthened or not-shortened) durational accents. This ‘bounce’ is organic and is, necessarily, mercurial and musically egalitarian.

Time is now just something that goes by. … It’s not 4/4 or 6/8, it’s just a steady flow of pulses

As we have seen, Dave sits alongside the likes of Don Cherry, Duke Ellington and others with ‘category intolerance’.Not only does Dave liberate playing temporally, but also contextually; or, rather, beyond the ‘contextual’ horizons retroactively imposed upon older forms of expression by the zeitgeist. It is not a kitsch collage, but a de-fetishised presentation. ‘Known’ pieces emerge from a natural, organic musical environment for fresh consideration.

The resulting polyglot musical landscape empowers Dave to ‘open up people to different music’ away from reductive views of music and ‘from what [they] would normally listen to’. Dismantling the rhetorical construction of ‘genre’, Dave uses ‘known material’ relative to both The Drumhedz and the audience: a point from which The Drumhedz improvise, and an identifiable crux from which the audience can explore previously unfamiliar musical styles and cultures. Dave reinforces this with his playing, freely changing from swing to bembe (above), adapting the schemata of musical construction and perception in real time, by tapping into various stylistic cultures and histories, changing how tunes are both conceived and received.

Rhythmic palimpsest is clear, as Dave connects aspects of beats from various contexts, time signatures and feels together. Dave’s groove often contains pulses based on multiple feels simultaneously (in the final example: crotchet, duple, triplet quaver and semiquaver), seemingly affecting stream segregation.Even Dave’s backbeat – the most dependable of temporal markers – fluctuates between pulses and placement within the beat. Drawing on Dilla’s work, the beats Dave plays appear microrhythmically derived rather than metrical.

As though in direct conversation with Tate, Dave humanises that which is predominantly computerised, by recreating electronic sounds and productive modes acoustically. In this sonic register and by using other people’s work as a departure point, Dave challenge’s conceptions of ownership and consumption, toying with the separation between the context and content of his influences. By manipulating the content and applying new contexts upon them, Dave’s audiences consume his ‘audio excerpts’ as a process, a live medley. Because anything can be edited or transformed, nothing can ever be defined as definitive; everything is always-already open to (re)adaptation. Utilising musical allusions and excerpts from a smorgasbord of contexts and styles, Dave gives the audience a vision of the possibilities of genre-less music as an always-already ever-evolving process. All of this is achieved from Dave’s drum stool.

Swing’s skip note

Skip(ped) beats and microrhythmic ‘imperfections’ inherent in The Drumhedz interpersonal interpretations of feel lends the music a sense of swing, a ‘bounce’. Listeners thus become co-authors of the event, determining their response by their understanding of the rhythmic interaction.

‘The Eye of The Hurricane’ is played more than an allusion to the tune, but less than a performance. Hancock’s conceptual hurricane rapidly enters, wreaks its havoc and just as rapidly dissipates. The nature of a composition and(/or) its internal concept becomes The Drumhedz’s known material, their improvisational spring board, a start point to which they may or may not return. Despite alluding to famous passages of music, The Drumhedz hardly ‘play’ the songs conventionally. Rarely do they state the literal information contained in a composed piece, instead performing as a collective autonomy through the piece; they fade in and out of songs as though one were tuning a radio.