Liv Ullmann (1977) about her relationship with Bergman: ‘after a short time I was confronted with his jealousy, violent and without bounds’ (p. 110). At the same time she states: ‘To work with Ingmar is to work on a discovery journey toward my own self’ (p. 224).

One student during the interview (see supplement 3: Response on interview questions) responded: ‘I had a hard time expressing myself verbally. Especially through music I can really speak’. Another interviewee (a singer) said: ‘I write my own lyrics that are personal. They contain wisdom that is still hard to achieve in my own thinking’.

In 2017 Griet Op de Beeck published her fourth book: Het beste wat we hebben [the best we have] (2017). Her previous books deal with the topic of covering secrets within the context of a family, creating an almost suffocating atmosphere. The title of an article in NRC (Veen, NRC Weekend, September 9 2017) speaks for itself: Nu moet het maar eens over de grote wonde gaan [finally let’s bring up the big wound]. She explains in the article ‘I think it’s only since a few years that I am able to connect to people’. Her new book directly deals with incest, which is also her personal experience.

The example of John Lennon also reveals a different way of speaking directly in an indirect way that is close to art: humour. Famous is his announcement during a performance on November 4th 1963, for the Royal family: ‘Will the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands? And for the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewellery.’ The rich English tradition of humour in general could easily be seen as an indirect way of speaking directly, maybe a way of dealing with embarrassment within the English society. Michael Lowis, (in Kaufman et al. 2014, p. 365) points out several aspects of humour that are similar to creativity, like being able to see multiple perspectives, accept ambiguity and relieving anxiety.

Another interesting example is a book from Charlotte Mutsaers: Harnas van hansaplast. In the book she describes a character, which leads a very complicated and destructive life and finally commits suicide at the age 51. This character is being displayed as her brother. Especially a passage in the book where she reportedly tries to sell the child porn her brother left behind, leads to outrage after an interview on Dutch television. There is confusion about who is being interviewed, her ‘the author’ or her ‘the character’ in the book. ‘I am allowed to lie as much as I want’ she explains in an interview (NRC Weekend, 4-11-2017). This illustrates the confusion that can be created of where facts end and where fiction begins. She claims that this part in the book is there to illustrate that she can also sympathise with her brother and therefore wants to reduce the distance between her and him by doing what she did. In the interview she describes her brother as being lonely but also brilliant and humorous. They both had to deal with a complicated childhood; this is what unifies them. The indirect way of a novel gives her the freedom to speak directly without being too vulnerable, until the media jump on her story and force her to reveal the truth. Interesting about this example is, that it also illustrates how a narrative can be created during a conversation (interview).

One of the interviewees (see supplement 3: Response on interview questions) mentioned: ‘I tried to make things perfectly and please other people. It has a positive side but I also miss the bigger picture’. Another one responded: ‘My work should be something about me and about what I feel, it should not just be beautiful’.

Chapter 3.3

The artist in reactive mode

If the artist as a person is struggling with his own issues - making him go into reactive mode - it might also affect his work (also see 3.4: Art and mental health). Even if he has the intention to connect in a dialogical way, his own needs could (partly) turn his work/performance into an attempt to receive something from the viewer/listener, like recognition, approval, control, confirmation of his view of the world, etc. This aspect of his work might interfere with its dialogical position. The part where he is expressing his needs through child mode could put his audience into an object position, having to prove that the artist is great or that he matters. This could interfere with the audience expecting an experience where they are free to connect and not be intimidated with arrogance; narcissism; or having to struggle with the feelings the artist cannot feel. It might even prevent the audience from being able to connect to themselves. From what I presented in the previous sections, it’s interesting to look at the following examples concerning art and connecting. It is important to note that this is not an attempt to give an ultimate judgement about specific artists, or art works being a result of either a dialogical position or using the audience as an object. However, the person of the artist in reactive mode could interfere with the ability of the viewer/listener to open up and fully appreciate his work. It could (partly) make his work not trustworthy enough to connect to.

John Lennon grew up in a complex context. He protected his vulnerability very well by being cynical to people around him, like journalists (Riley 2011). They were his objects. In his music and lyrics however, he could be more vulnerable and speak directly, as the following excerpt (figure 4) of the lyrics of his song Mother might reveal.

|

Mother, you had me But I never had you So I just got to tell you goodbye, goodbye |

Father, you left me But I never left you But you didn't need me |

Figure 4: Mother, John Lennon © Universal Music Publishing Group, Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

The tragic of his story is that what happened to him, he also did to his own son Julian who was named after his mother Julia. He left the family. This is what Boszormenyi-Nagy would describe as the revolving slate (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark 1973), victim becoming perpetrator (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position). Being treated as an object, John is entitled to treat others as an object, without empathy.

In regard to art and speaking directly it is interesting to also include writers. They also express themselves creatively, connecting to themselves and addressing their audience. In his book: The courage to write, Ralph Keyes (1995) mentions several examples of writers like Elwin Brooks White that took the courage to speak directly in their work. ‘Much of the story about E. B. White is how he has come to terms with his fears’ (p. 5). Writer Arthur Miller states: ‘The best work that anybody ever writes is the work that is on the verge of embarrassing him, always’ (Evans 1969, p. 73). Apart from needing the courage to speak directly, writers might be in a more comfortable position. Assuming that verbalizing is also part of their talent, they are free to create narratives (also see 2.1.3: Inner dialogue). They can reveal autobiographical elements in it but still be free to choose a safer way by creating a character, by using metaphors, or a story that contains fiction at the same time.

According to Sebastian Dieguez (2011) Michael Jackson ‘played with children, slept with children and lived like a child’ (p. 171). His estate in California: Neverland is none other than a fantasy island described in the story Peter Pan, a place where children never grow up (p. 167). Maybe partly as an artist (his singing voice was not a mature voice) but certainly as a person he created a world and an image of himself, inviting the people around him and maybe the rest of the world to play a part in it. This puts them (and us) in an object position, apparently - according to the documentary Leaving Neverland (HBO 2019) - with extreme results. At the same time music seemed to be Michael’s outlet, as he stated in an interview (Dieguez, p. 166). Michael Jackson’s example (the person as well as the music) also contains elements of the next category, acting out what cannot be verbalized.

3.3.2 Art and expressing what cannot be verbalized, acting out

If the artist speaks through action, the audience - like parents dealing with their children - will have to decode what the artist wants to share, with the danger that what is implicit, stays implicit. If reflexes dominate his expression instead of reflection (also see 1.2.1: Scripts in an object position; 2.2: Art and inner dialogue), the artist’s behaviour is reactive and not meant to be dialogical. It becomes a primary or secondary form of expression. The viewer/ listener is put into an object position but an audience might not be willing to act like parents.

Dutch painter Karel Appel discussed his way of painting in an interview by Jan Vrijman for the magazine Vrij Nederland (January 29, 1955): ‘I just mess around a little. These days I put it on nice and thick, I slam on the paint with brushes, putty knives and my bare hands, sometimes I throw on complete pots at once.’ Topics of his paintings were innocent child-creatures and fantasy animals. His inspiration came from the way in which people with a mental disability express when they draw. At that time the work of Karel Appel gave rise to remarks like ‘even I can do this’. People considered Appel to never think about colour and composition, to just express like a child and spontaneously slam paint on the canvas. For them he got away with it because he was so gifted. Hans Hartog de Jager (in NRC, January 16 2016) argues this idea is now being contested because the Gemeentemuseum in 2016 exhibited no less than sixty drawings of Appel, many of them pre-studies of paintings shown further on in the museum. Besides the fact that having the reflection to explore expressing like a child proves he is not in child-mode, Appel appears to also have contemplated, planned and composed while dealing with his work.

The auto-destructive act of the pop-band The Who could be considered an artistic expression, following the example of Gustav Metzger. It consisted of the band destroying their equipment. At the same time it could be considered a primary or secondary expression, saying what cannot be said by acting out. The Who’s guitarist, Pete Townshend, apparently was abused as a child (Townshend 2012, p. 24), which might have a connection with his destructive acts on stage. His rock opera, Tommy (the one who could not speak), however, is simultaneously a way of pointing at saying what cannot be said (also see 3.3.1: Art and speaking directly).

3.3.3 Art and narcissism

Narcissism is often described as feeling superior to others, fantasizing about personal successes, and believes of deserving a special treatment (DSM, American Psychiatric Association 2015). Narcissistic individuals can become aggressive when they feel being humiliated. Many therapists believe narcissism can be traced back to childhood. According to Alice Miller (1983) it happens when parents experience their children as part of themselves. Their children fulfil their needs and therefore learn to ignore their own feelings and needs. These needs might be presented to their environment later (p. 57), turning them into objects of their needs (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position). Recent research (Brummelman, Thomaes et al. 2015) seems to confirm this, claiming parents, who over-evaluate their children, create narcissism. They state children internalize their parents view on them(e.g. ‘I am superior to others’ and ‘I am entitled to privileges’).

Similar to narcissism, arrogance is a protection of someone’s vulnerability stemming from a child-script. It could be a safer position for an artist to impress or even intimidate his audience. Of course art that goes along with virtuosity easily leans itself well to being impressive.

Both narcissism and arrogance help avoiding the risk involved in connecting in a dialogic way. In an article (Ribbens & Snoeijen, NRC 14-2-19) Dutch Photographer Erwin Olaf gives comments about his self-portraits. About Tar and Feathers (2012) he comments: ‘not a highlight in my career as a self-portrait artist (see image 11). With these pictures I allowed myself to be fuelled too much by anger. A good learning experience, I am the one that doesn’t match. If I could have had the photo’s laying around for a longer period, I also would have photo shopped them less arrogant’. He also explained in an earlier interview (Koelewijn, NRC weekend November 2012) that Tar and Feathers refers to two events in his life that made him feel very vulnerable and had a big impact on his identity being gay: an experience with the principal of the school when he was young and another with a reporter later in his career.

Pop music seems to offer ample ways of displaying narcissism. Pop artist Prince created an image of narcissism and maybe played with this idea in his stage personality. Though he always denied that Purple Rain was autobiographical, the movie depicted a troubled father-son relationship. The relations with his father got worse as Prince came of age. According to Chris Heath, (Magazine GQ, April 21 2016) on at least one occasion Prince was thrown out of the house. Pleading to be allowed back, he spent two hours in a phone booth crying. He later claimed that this was the last time he ever cried. Barney Hoskins (In The Observer, April 24 2016), doing an interview with Prince, wrote: ‘[…] I finally got to interview the guy. Except it wasn’t so much an interview as a sadistic grilling by a brilliant but somewhat paranoid narcissist who howled with laughter at the notion that anyone other than he himself was qualified to speak about his music’. This could mean his artistic work was partly there to confirm his status. At the same time it is possible that feeling less vulnerable in his work, he is also able to speak directly in an indirect way there.

3.3.4 Art and pleasing the audience

Where narcissism could be regarded as disconnecting from the other, pleasing the audience by trying to figure out what they want, can be considered as disconnecting from yourself. Both are opposite ways of protecting vulnerability, dealing with your needs by putting the other into an object position. Pleasing the other is not to be confused by displaying empathy towards the other in a reciprocal relationship.

The need to please her audience and getting acknowledgement in return could have played a role in the sad end or the career of Maria Callas. She was doing a come back world tour in 1973. ‘Despite the horrors of each performance, for Maria, who got more and more hopeless and desperate, it was a necessary confirmation of the fact that she was loved’ (Stassinopoulos 1987, p. 250).

Marina Abramovic commented about her earlier work, producing paintings for relatives:

‘I would do whatever they wanted and I would sign these paintings with a huge MARINA on the bottom in blue. […] But I want to die when I see these canvases, because I did them for money, and with no feeling. I consciously made them kitschy, and dashed them off in fifteen minutes’ (Abramovic 2016, p. 37).

Youri Egorov escaped from the Soviet Union being 23 and settled in Amsterdam. Jan Brokken (2008) describes his destructive lifestyle, which Brokken beliefs caused him to get an AIDS HIV infection. He died at age 34. ‘From his earliest youth he had to fulfil the desires of others. He was six when his mother decided to turn him into a great pianist. […] The start of the war caused her to stop her piano studies, she could not make her little girl’s dream come true. This loss, he should make up for, on his own’ (p. 19). The example of Youri Egorov also shows elements of the next category: destructive entitlement. He stated: ‘I know I will not get old’ (p. 213) (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position).

3.3.5 Art and destructive entitlement

Destructive entitlement is the concept that describes victim becoming perpetrator (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position). Destructive entitlement can go outwards (e.g. aggression) or inwards (e.g. addiction) (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Krasner 1986, p. 111). Besides narcissism, Pop music offers ample room for dealing with destructive entitlement. Stage acts displaying destructive behaviour is an accepted phenomenon in the Pop world and the performance is not always negatively affected by a destructive lifestyle. Kurt Cobain, from the very popular band Nirvana during the nineties, had a tragic youth. His parents divorced when he was at the age of eight. His behaviour on stage could be very destructive, destroying his equipment and harming himself. After he died the police found guns in his house. He was using heroin and his girl friend also got addicted. She even gave birth to their son being addicted and eventually the marriage went on the rocks. His lyrics were very dark, showing a negative self-image and a negative view on others: ‘I feel stupid and contagious/ here we are now/ entertain us’ (Dieguez 2011). He committed suicide in 1994.

Amy Winehouse too had a complicated background and developed several addictions. The documentary Amy (Kapadia 2015) illustrates how she developed a complicated relationship with her father. He left the house when she was young but later he became her manager, organizing concerts until the day before she died. That also affected her relation to her father, being an object in his needs. Her destructive behaviour mainly was turned inwards but her relationship with her boy friend was also very destructive. In her music she was able to speak directly, connect to others while being connected to herself. Sadly at the end of her life she also lost that and many of her fans felt being treated as an object and expressing this by booing her during her last concerts, as can be observed in many videos on YouTube.

The most striking part of the earlier career of Marina Abramovic as a performance artist is the fact that she used to put herself in dangerous positions during her performances. She created situations where she was dependent on the trustworthiness of others. During a performance Rhythm 0 (1974) she allowed the audience to do what ever they liked with 72 objects she made available during the performance. They could be hurtful if they wanted, Mariana stated: ‘I wanted to test the limits of how far the public would go, if I didn’t do nothing at all’ (Abramovic 2016, p. 71). With this performance she created a situation of being an object to the audience with the danger of them hurting her, and actually some of them behaved quite sadistically, like putting a loaded gun in her hand and pointing it at her. This also touched her and after the performance Rhythm O she avoided seeing or speaking to anyone of that audience again (Lint 2013). From a different perspective the audience could also be considered as being her object, presenting them the pain she could not deal with herself, the pain of her own past. ‘The worst part was when my father would come home in the middle of the night and my mother would go crazy and they would start beating each other. Then she would run into my room and pull me out of bed and hold me in front of her like a shield, so that he would stop beating her. […] To this day I can’t stand, ever, anybody raising their voice in anger. When someone does that, I just completely freeze’ (Abramovic 2016, p. 19). Marina thinks her cold upbringing also helped her to have stamina: ‘I was expected to endure this punishment without complaint. I think in a way my mother was training me to be a soldier like her’ (p. 11). The connection to her parents seems to make it impossible to also allow in the perspective of it also being hurtful. Her famous performance: The artist is present in the MoMA in 2010 literally shows Mariana in a more dialogical position with her audience. ‘Hearts were opened to me and I opened my heart in return, time after time after time. I opened my heart to each one, then closed my eyes – and then there was always another' (p. 318).

3.3.1 Art and speaking directly

If in his daily life speaking directly is difficult in dealing with other people, it might be easier for the artist to connect to himself and speak directly through his work. Maybe art for him is a more indirect or safer way of connecting in a dialogic way and speak directly.

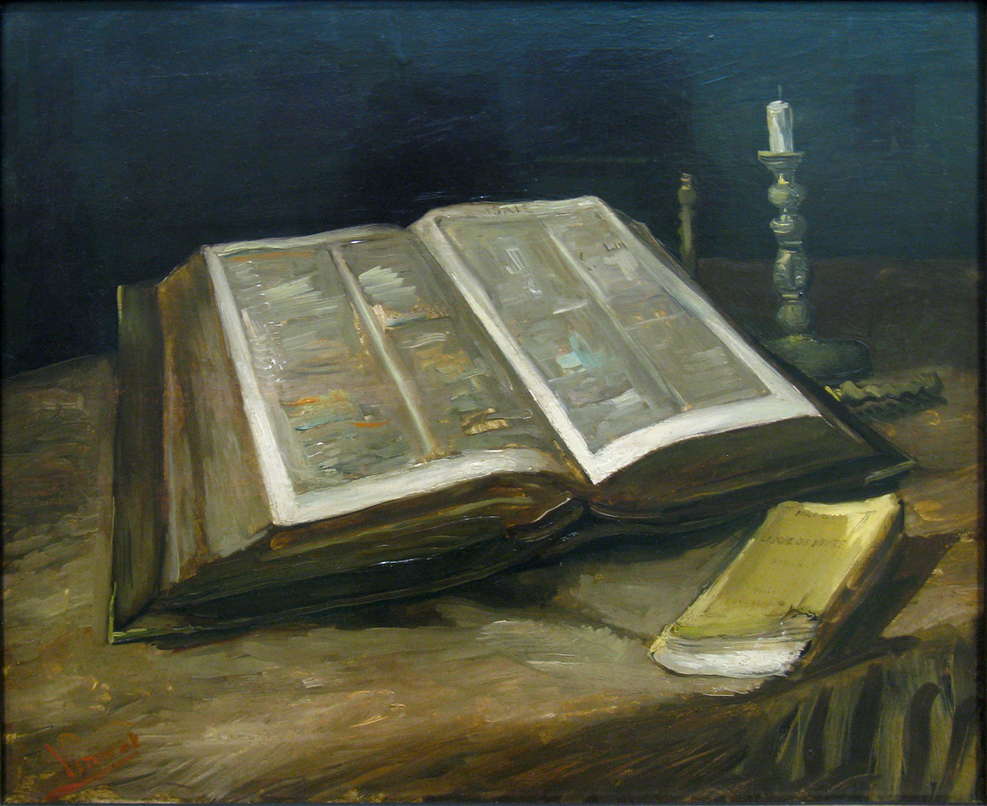

Vincent van Gogh’s personality disorders (also see 3.4: Art and mental health) are claimed to have resulted from a complicated childhood with the lack of empathy from his mother and harsh devaluation from his father (Meissner 1994). Vincent was said to be a replacement child for his deceased brother and wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father being a minister. His painting: Still with bible (1885) could be seen as his attempt to speak directly. It was his last painting before he moved to France, displaying the Holy bible and Emile Zola’s La joie de vivre as a metaphor for his dilemma of connecting to his context or being connected to himself (see image).

Alice Miller (1979) points at speaking directly when she claims that filmmaker Ingmar Bergman - apart from projection and denial - had other possibilities for dealing with his suffering by making films. At the same time she points at Bergman using the audience as an object, when she mentions: ‘It is conceivable that we as the movie audience, have to endure the feelings that he, the son of such a father, could not experience overtly but nevertheless carried with him’ (p. 96).

|

Casus singing female 20 |

|

|

|

Casus Art Science male 24 |

|

|

|

Casus Graphic Design male 21 |

|

|

|

Casus composition male 25 |

|

|

|

Casus Fine Art female 23 |

|

|

|

Casus fine arts male 22 |

|

|

|

Casus singing female 24 |

|

|

|

Casus fine art male 25 |

|

|

Chapter 3.3

The artist in reactive mode

If the artist as a person is struggling with his own issues - making him go into reactive mode - it might also affect his work (also see 3.4: Art and mental health). Even if he has the intention to connect in a dialogical way, his own needs could (partly) turn his work/performance into an attempt to receive something from the viewer/listener, like recognition, approval, control, confirmation of his view of the world, etc. This aspect of his work might interfere with its dialogical position. The part where he is expressing his needs through child mode could put his audience into an object position, having to prove that the artist is great or that he matters. This could interfere with the audience expecting an experience where they are free to connect and not be intimidated with arrogance; narcissism; or having to struggle with the feelings the artist cannot feel. It might even prevent the audience from being able to connect to themselves. From what I presented in the previous sections, it’s interesting to look at the following examples concerning art and connecting. It is important to note that this is not an attempt to give an ultimate judgement about specific artists, or art works being a result of either a dialogical position or using the audience as an object. However, the person of the artist in reactive mode could interfere with the ability of the viewer/listener to open up and fully appreciate his work. It could (partly) make his work not trustworthy enough to connect to.

3.3.1 Art and speaking directly

If in his daily life speaking directly is difficult in dealing with other people, it might be easier for the artist to connect to himself and speak directly through his work. Maybe art for him is a more indirect or safer way of connecting in a dialogic way and speak directly.

John Lennon grew up in a complex context. He protected his vulnerability very well by being cynical to people around him, like journalists (Riley 2011). They were his objects. In his music and lyrics however, he could be more vulnerable and speak directly, as the following excerpt (figure 4) of the lyrics of his song Mother might reveal.

|

Mother, you had me But I never had you So I just got to tell you goodbye, goodbye |

Father, you left me But I never left you But you didn't need me |

Figure 4: Mother, John Lennon © Universal Music Publishing Group, Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

The tragic of his story is that what happened to him, he also did to his own son Julian who was named after his mother Julia. He left the family. This is what Boszormenyi-Nagy would describe as the revolving slate (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark 1973), victim becoming perpetrator (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position). Being treated as an object, John is entitled to treat others as an object, without empathy.

Vincent van Gogh’s personality disorders (also see 3.4: Art and mental health) are claimed to have resulted from a complicated childhood with the lack of empathy from his mother and harsh devaluation from his father (Meissner 1994). Vincent was said to be a replacement child for his deceased brother and wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father being a minister. His painting: Still with bible (1885) could be seen as his attempt to speak directly. It was his last painting before he moved to France, displaying the Holy bible and Emile Zola’s La joie de vivre as a metaphor for his dilemma of connecting to his context or being connected to himself (see image).

Alice Miller (1979) points at speaking directly when she claims that filmmaker Ingmar Bergman - apart from projection and denial - had other possibilities for dealing with his suffering by making films. At the same time she points at Bergman using the audience as an object, when she mentions: ‘It is conceivable that we as the movie audience, have to endure the feelings that he, the son of such a father, could not experience overtly but nevertheless carried with him’ (p. 96).

In regard to art and speaking directly it is interesting to also include writers. They also express themselves creatively, connecting to themselves and addressing their audience. In his book: The courage to write, Ralph Keyes (1995) mentions several examples of writers like Elwin Brooks White that took the courage to speak directly in their work. ‘Much of the story about E. B. White is how he has come to terms with his fears’ (p. 5). Writer Arthur Miller states: ‘The best work that anybody ever writes is the work that is on the verge of embarrassing him, always’ (Evans 1969, p. 73). Apart from needing the courage to speak directly, writers might be in a more comfortable position. Assuming that verbalizing is also part of their talent, they are free to create narratives (also see 2.1.3: Inner dialogue). They can reveal autobiographical elements in it but still be free to choose a safer way by creating a character, by using metaphors, or a story that contains fiction at the same time.

According to Sebastian Dieguez (2011) Michael Jackson ‘played with children, slept with children and lived like a child’ (p. 171). His estate in California: Neverland is none other than a fantasy island described in the story Peter Pan, a place where children never grow up (p. 167). Maybe partly as an artist (his singing voice was not a mature voice) but certainly as a person he created a world and an image of himself, inviting the people around him and maybe the rest of the world to play a part in it. This puts them (and us) in an object position, apparently - according to the documentary Leaving Neverland (HBO 2019) - with extreme results. At the same time music seemed to be Michael’s outlet, as he stated in an interview (Dieguez, p. 166). Michael Jackson’s example (the person as well as the music) also contains elements of the next category, acting out what cannot be verbalized.

3.3.2 Art and expressing what cannot be verbalized, acting out

If the artist speaks through action, the audience - like parents dealing with their children - will have to decode what the artist wants to share, with the danger that what is implicit, stays implicit. If reflexes dominate his expression instead of reflection (also see 1.2.1: Scripts in an object position; 2.2: Art and inner dialogue), the artist’s behaviour is reactive and not meant to be dialogical. It becomes a primary or secondary form of expression. The viewer/ listener is put into an object position but an audience might not be willing to act like parents.

Dutch painter Karel Appel discussed his way of painting in an interview by Jan Vrijman for the magazine Vrij Nederland (January 29, 1955): ‘I just mess around a little. These days I put it on nice and thick, I slam on the paint with brushes, putty knives and my bare hands, sometimes I throw on complete pots at once.’ Topics of his paintings were innocent child-creatures and fantasy animals. His inspiration came from the way in which people with a mental disability express when they draw. At that time the work of Karel Appel gave rise to remarks like ‘even I can do this’. People considered Appel to never think about colour and composition, to just express like a child and spontaneously slam paint on the canvas. For them he got away with it because he was so gifted. Hans Hartog de Jager (in NRC, January 16 2016) argues this idea is now being contested because the Gemeentemuseum in 2016 exhibited no less than sixty drawings of Appel, many of them pre-studies of paintings shown further on in the museum. Besides the fact that having the reflection to explore expressing like a child proves he is not in child-mode, Appel appears to also have contemplated, planned and composed while dealing with his work.

The auto-destructive act of the pop-band The Who could be considered an artistic expression, following the example of Gustav Metzger. It consisted of the band destroying their equipment. At the same time it could be considered a primary or secondary expression, saying what cannot be said by acting out. The Who’s guitarist, Pete Townshend, apparently was abused as a child (Townshend 2012, p. 24), which might have a connection with his destructive acts on stage. His rock opera, Tommy (the one who could not speak), however, is simultaneously a way of pointing at saying what cannot be said (also see 3.3.1: Art and speaking directly).

3.3.3 Art and narcissism

Narcissism is often described as feeling superior to others, fantasizing about personal successes, and believes of deserving a special treatment (DSM, American Psychiatric Association 2015). Narcissistic individuals can become aggressive when they feel being humiliated. Many therapists believe narcissism can be traced back to childhood. According to Alice Miller (1983) it happens when parents experience their children as part of themselves. Their children fulfil their needs and therefore learn to ignore their own feelings and needs. These needs might be presented to their environment later (p. 57), turning them into objects of their needs (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position). Recent research (Brummelman, Thomaes et al. 2015) seems to confirm this, claiming parents, who over-evaluate their children, create narcissism. They state children internalize their parents view on them(e.g. ‘I am superior to others’ and ‘I am entitled to privileges’).

Similar to narcissism, arrogance is a protection of someone’s vulnerability stemming from a child-script. It could be a safer position for an artist to impress or even intimidate his audience. Of course art that goes along with virtuosity easily leans itself well to being impressive.

Both narcissism and arrogance help avoiding the risk involved in connecting in a dialogic way. In an article (Ribbens & Snoeijen, NRC 14-2-19) Dutch Photographer Erwin Olaf gives comments about his self-portraits. About Tar and Feathers (2012) he comments: ‘not a highlight in my career as a self-portrait artist (see image 11). With these pictures I allowed myself to be fuelled too much by anger. A good learning experience, I am the one that doesn’t match. If I could have had the photo’s laying around for a longer period, I also would have photo shopped them less arrogant’. He also explained in an earlier interview (Koelewijn, NRC weekend November 2012) that Tar and Feathers refers to two events in his life that made him feel very vulnerable and had a big impact on his identity being gay: an experience with the principal of the school when he was young and another with a reporter later in his career.

Pop music seems to offer ample ways of displaying narcissism. Pop artist Prince created an image of narcissism and maybe played with this idea in his stage personality. Though he always denied that Purple Rain was autobiographical, the movie depicted a troubled father-son relationship. The relations with his father got worse as Prince came of age. According to Chris Heath, (Magazine GQ, April 21 2016) on at least one occasion Prince was thrown out of the house. Pleading to be allowed back, he spent two hours in a phone booth crying. He later claimed that this was the last time he ever cried. Barney Hoskins (In The Observer, April 24 2016), doing an interview with Prince, wrote: ‘[…] I finally got to interview the guy. Except it wasn’t so much an interview as a sadistic grilling by a brilliant but somewhat paranoid narcissist who howled with laughter at the notion that anyone other than he himself was qualified to speak about his music’. This could mean his artistic work was partly there to confirm his status. At the same time it is possible that feeling less vulnerable in his work, he is also able to speak directly in an indirect way there.

3.3.4 Art and pleasing the audience

Where narcissism could be regarded as disconnecting from the other, pleasing the audience by trying to figure out what they want, can be considered as disconnecting from yourself. Both are opposite ways of protecting vulnerability, dealing with your needs by putting the other into an object position. Pleasing the other is not to be confused by displaying empathy towards the other in a reciprocal relationship.

The need to please her audience and getting acknowledgement in return could have played a role in the sad end or the career of Maria Callas. She was doing a come back world tour in 1973. ‘Despite the horrors of each performance, for Maria, who got more and more hopeless and desperate, it was a necessary confirmation of the fact that she was loved’ (Stassinopoulos 1987, p. 250).

Marina Abramovic commented about her earlier work, producing paintings for relatives:

‘I would do whatever they wanted and I would sign these paintings with a huge MARINA on the bottom in blue. […] But I want to die when I see these canvases, because I did them for money, and with no feeling. I consciously made them kitschy, and dashed them off in fifteen minutes’ (Abramovic 2016, p. 37).

Youri Egorov escaped from the Soviet Union being 23 and settled in Amsterdam. Jan Brokken (2008) describes his destructive lifestyle, which Brokken beliefs caused him to get an AIDS HIV infection. He died at age 34. ‘From his earliest youth he had to fulfil the desires of others. He was six when his mother decided to turn him into a great pianist. […] The start of the war caused her to stop her piano studies, she could not make her little girl’s dream come true. This loss, he should make up for, on his own’ (p. 19). The example of Youri Egorov also shows elements of the next category: destructive entitlement. He stated: ‘I know I will not get old’ (p. 213) (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position).

3.3.5 Art and destructive entitlement

Destructive entitlement is the concept that describes victim becoming perpetrator (also see 2.2.1: Scripts in an object position). Destructive entitlement can go outwards (e.g. aggression) or inwards (e.g. addiction) (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Krasner 1986, p. 111). Besides narcissism, Pop music offers ample room for dealing with destructive entitlement. Stage acts displaying destructive behaviour is an accepted phenomenon in the Pop world and the performance is not always negatively affected by a destructive lifestyle. Kurt Cobain, from the very popular band Nirvana during the nineties, had a tragic youth. His parents divorced when he was at the age of eight. His behaviour on stage could be very destructive, destroying his equipment and harming himself. After he died the police found guns in his house. He was using heroin and his girl friend also got addicted. She even gave birth to their son being addicted and eventually the marriage went on the rocks. His lyrics were very dark, showing a negative self-image and a negative view on others: ‘I feel stupid and contagious/ here we are now/ entertain us’ (Dieguez 2011). He committed suicide in 1994.

Amy Winehouse too had a complicated background and developed several addictions. The documentary Amy (Kapadia 2015) illustrates how she developed a complicated relationship with her father. He left the house when she was young but later he became her manager, organizing concerts until the day before she died. That also affected her relation to her father, being an object in his needs. Her destructive behaviour mainly was turned inwards but her relationship with her boy friend was also very destructive. In her music she was able to speak directly, connect to others while being connected to herself. Sadly at the end of her life she also lost that and many of her fans felt being treated as an object and expressing this by booing her during her last concerts, as can be observed in many videos on YouTube.

The most striking part of the earlier career of Marina Abramovic as a performance artist is the fact that she used to put herself in dangerous positions during her performances. She created situations where she was dependent on the trustworthiness of others. During a performance Rhythm 0 (1974) she allowed the audience to do what ever they liked with 72 objects she made available during the performance. They could be hurtful if they wanted, Mariana stated: ‘I wanted to test the limits of how far the public would go, if I didn’t do nothing at all’ (Abramovic 2016, p. 71). With this performance she created a situation of being an object to the audience with the danger of them hurting her, and actually some of them behaved quite sadistically, like putting a loaded gun in her hand and pointing it at her. This also touched her and after the performance Rhythm O she avoided seeing or speaking to anyone of that audience again (Lint 2013). From a different perspective the audience could also be considered as being her object, presenting them the pain she could not deal with herself, the pain of her own past. ‘The worst part was when my father would come home in the middle of the night and my mother would go crazy and they would start beating each other. Then she would run into my room and pull me out of bed and hold me in front of her like a shield, so that he would stop beating her. […] To this day I can’t stand, ever, anybody raising their voice in anger. When someone does that, I just completely freeze’ (Abramovic 2016, p. 19). Marina thinks her cold upbringing also helped her to have stamina: ‘I was expected to endure this punishment without complaint. I think in a way my mother was training me to be a soldier like her’ (p. 11). The connection to her parents seems to make it impossible to also allow in the perspective of it also being hurtful. Her famous performance: The artist is present in the MoMA in 2010 literally shows Mariana in a more dialogical position with her audience. ‘Hearts were opened to me and I opened my heart in return, time after time after time. I opened my heart to each one, then closed my eyes – and then there was always another' (p. 318).