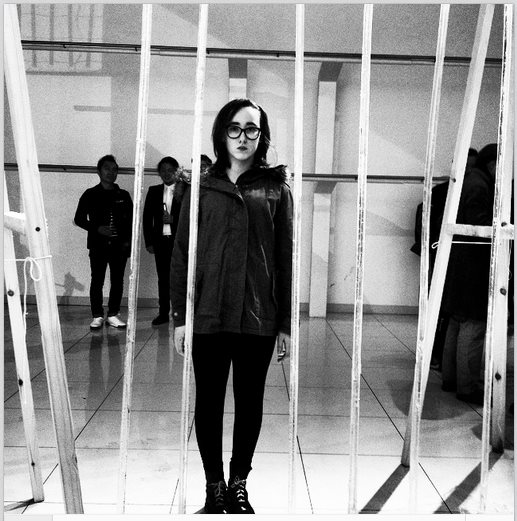

The second time I exhibited the artwork I altered the design to look more like champagne glasses and filled these with sparkling wine. I created 28 in a line diagonally stretching the entire ground floor of Unit 24 Gallery with gaps just too small to manoeuvre through. The stems of the glasses formed prison bars across the gallery that initially prevented people crossing the space into the gallery and to the bar. For an hour no one crossed the line of glasses however once the first ones fell other viewers started taking risks and by the end of the night none were left standing. The installation of the work had not gone entirely to plan since the gallery temperature was warm and the glass wax bases, which had to be set in situ for them to balance, did not set before the opening. Half an hour into the private view they had set and at that point I removed the string they were hanging by. This unintended performance worked very effectively as I could see people watching tensely waiting for each one to fall as they gently swayed when I removed the string. My care in removing the string and the obvious wobble of the glasses accentuated their fragility as well as allowing the viewer to see part of the risky process of making them. My handling the glasses may also have provided a needed disruption to the conventional restriction of not touching artwork in a gallery setting. People started gently touching them after they saw me interacting with them.

Alice O’Grady suggests that;

Participatory practice can be understood as interplay between artists/performers taking risks and making themselves vulnerable and audience members/participants being encouraged to take risks through various degrees of physical involvement. This interplay creates paradoxical feelings of vulnerability and agency on both sides’ (2017: 15).

Participatory art practice is effective by ‘drawing spectators’ attention to their own physical and emotional presence’ (O’Grady 2017: 13). In this installation I wanted the viewer to be able to experience the physical risk to the work and to themselves (most people do not have much knowledge of glass wax to understand that it’s safe).To achieve this the work has to be right on an edge between being safe and being destroyed; on restricting movement and encouraging breaking. It is only here that both the participant and I experience the tension of risk and power of our own agency.

Right: Video of the making and breaking of Celebration 2015

filmed by Emma Lou Hill

Click image to play

In my first bone china sculptural installation fragility 2007 the bone china walls were glued together using glaze. This created safety problems for exhibiting as the glaze had glass sharp edges when broken leaving a high risk of the viewer becoming injured. In researching other materials I found glass wax; glass wax is completely safe despite looking like glass and breaking like glass. It is often used in prop-making as an alternative to sugar glass for making items to be broken. It can be re-melted several times over allowing a continual cycle of making and breaking. Initially I cast glass wax into the twig moulds, however, unlike most waxes the glass wax would not weld without cracking and breaking. Since I was unable to find a way to adhere the twigs together I decided to create one-piece tall fragile forms. This had been impossible in china due to limitations on the size of kilns.

When the first whole cast came out it was difficult to balance so I hung it upside down with fishing line from the ceiling. This happened to be the only way I could safely store it, however, the form looked much better this way up. The weight at the top of the form made it seem more precarious. In addition it now resembled a wine glass and I preferred the use of an everyday object to science equipment. I didn’t want to exhibit the work hanging because it would look too stable and safe so I devised a way of creating a base by pooling glass wax on the floor. When I cut the string for the first time I couldn’t believe they actually stood, swaying gently.

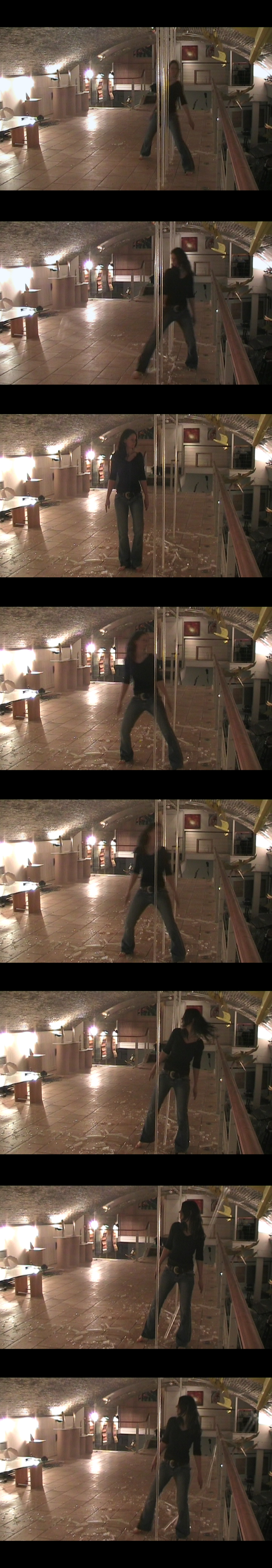

During the exhibition I realised it was people’s interaction in brushing by and causing the glasses to wobble that activated the work. This was accentuated during the private view when a performance artist incorporated my work in her performance. She took deliberate risks in moving parts of her body in and out of the glasses making some very quick and risky moves. This sense of risk was exactly what I had been looking to create in my artwork after my experiences of breaking bones. Amazingly the first time I exhibited this artwork it remained standing right through until the show was due to come down. Their positioning to the side of the gallery space had meant viewers did not have to walk too close so did not choose to take many risks with them. I felt disappointed the work remained standing; I had lost patience in being careful with it. Not only did I not want the hassle of manoeuvring the fragile pieces home but I also didn’t want them in my studio. It gets to a point where the continual risk of breaking becomes extremely aggravating as I no longer wanted my movement to be continually restricted by with the fragility of my environment.

I started by zigzagging through the stems of the glasses. Stepping in the space between them was not dissimilar to stepping over Salcedo’s crack in the experience of risk. Risk makes experiences seem more real to me. I feel more present with risk. This felt very similar to the experience of mountain biking where I am so focussed outside my body that I become extended into the environment. Weaving through the poles feels similar to going down a downhill track on my bike. When I am moving fast on my bike I am completely focused on the track and on creating a smooth route through. I feel powerful in the sense of agility and risk as I neatly dart through the fragile glass wax without disrupting it.

I expected I would accidentally touch the funnels as I moved through them but even where the gap is very narrow I manage to dive through without touching them. My movement causes a breeze that makes them gently but precariously sway. At one point I accidentally clip the glass on the end of the row. For a moment I feel really alive as I watch it; waiting for a second to see if it falls. I think it is coming down but actually it just rocks very precariously. I start to take more risks and move faster. The faster I move the more alive I feel. In taking risks with them I experience a sense of empowerment in the movement. I can feel them vibrate and gently sway after each of my passages through, and there is a sense of connection with them. I’m not just passing through the world at this point but interacting with it, it responds to my movement as much as I to it. It is more than a dual connection though, it is not me versus the funnels but a web of connections, feet to poles, feet to body, body to poles, one pole to another as the falling of one could bring down another. Maybe this feeling of part objects comes as my focus is extended into the world around me; in the state of extension the boundaries of self are not of importance. This opens up new dynamics and connections.

I continue to move faster and faster through the poles and eventually I push it far enough that my foot catches the bottom of one. I savour the expectation of it crashing to the ground. The glass wax does not break as loudly or melodically as the bone china but there is a satisfying crack as the bottom of the glass wax pole breaks. It reminds me of Poe’s House of Usher where the narrator hears the distant but eerie sound of the house being torn asunder as the crack threatens to widen. I accidentally clip a further couple of poles and each crash to maximum effect. The glass wax travels twenty to thirty feet away covering the entire of the gallery floor with smashed shards. Elijah in the film Unbreakable (2000) has brittle bones and carries a glass cane. As he falls down a set of stairs the cane smashes to destruction providing a visual representation of his bones. The shards on the floor of the gallery remind me of the shards of his cane after his fall.

In both my experience of taking risks moving through the glass wax funnels or in riding my bike I feel empowered; it is my decision to take these risks. So much of the time in life I feel restricted by perceived dangers or restricted by others deciding the limits of risk for you.

When I read Scott Lash and John Urry (1994: 33-35) I had been interested in their perception of the changing nature of risk. They suggested there had been a move from the main risks facing people being natural disasters to man-created ones. This could be advances in science that were not able to be fully tested in the laboratory and so had to be trialled in the real world. This led me to laboratory glass equipment and I decided to try making a conical flask. The translucence of glass wax enabled me to fill forms with different liquids and I liked the additional idea of risk in spilling. I wanted the forms to look and be precarious and wanted the flasks to be higher than people’s heads so the viewers’ relation to the installation would be physical.

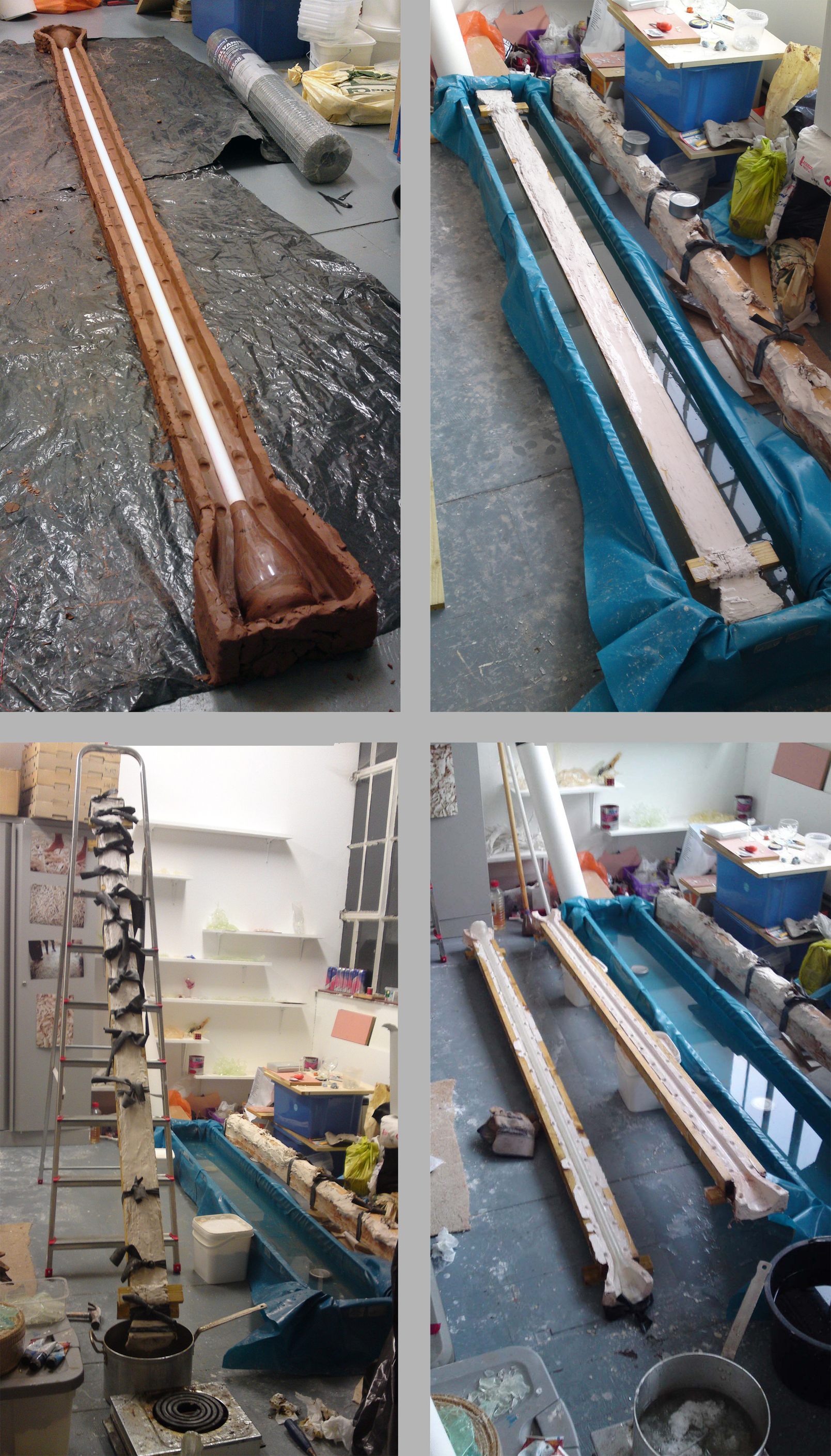

The entire process is precarious both for me and the work. The first mould was the longest mould I have ever made and I found the plaster flexed at that length. The flex was slightly nerve wracking when handling it and it broke after only five casts. I made the next mould with pieces of wood embedded on each side to solve this. The water bath contained twenty builders’ buckets of water and was only made from polythene sheet over 2”x1” timber! I had nightmares about the polythene sheet bursting and my studio and everyone else’s being flooded!

The next danger was tipping the molten glass wax. It melts at a much higher temperature than most waxes and sticks to skin inflicting burns. The mould being eight feet tall meant I had to climb a ladder with the pan of glass wax and pour it in above my head height. Molten glass wax frequently leaked out of the moulds and some burst at the seams. I had to learn where to clamp new moulds to prevent leaks and also predict when old moulds were fracturing. I can only just lift the mould and with the glass wax in it was dangerous to move. The excess glass wax must be tipped out of the mould before it sets if the cast is to be hollow. This involved holding the mould in the middle whilst it was still vertical, with the open end of the mould above my head, and then tipping, whilst aiming towards the saucepan, and finally resting the mould upside down on the ladder. I always felt quite relieved to be uninjured after completing this part of the process.

It took me days of attempts before I managed to get a whole cast from the glass wax and I almost gave up before a ceramicist friend suggested floating the glass wax out of the mould whilst it was still in the water bath. This worked but not every time. The turnaround time on this mould is about three hours because it takes this long to melt the glass wax and also to clean and reassemble the mould for the next pouring. Each time I opened the mould it was a similar nervous experience to casting the china twigs but accentuated. I was pleased if the whole had cast but then tense as I gently teased the glass wax from the mould. Each mould had a few sticking points where I had to apply a bit of pressure and allow the glass wax pole to flex to get it free. Many broke at these sticking points. I enjoyed the risk; similarly to mountain biking I could feel my dexterity improving as I became more skilled in releasing the glass from the mould and felt present and alive as I focused intently on the task aware that any moment the cast could unpredictably catch and fracture.

I found the whole process was intensely nerve wracking and to cap it all I still had no idea if I would be able to transport them to the gallery in one piece...