II. Organ vespers in the Netherlands

Dutch Protestant evening prayers

The tradition of evening prayer was not really reformed during the Reformation in the Netherlands and Germany in the sixteenth century. The main reformers did not disapprove of evening prayers, but they focused on the main services on Sunday morning. This resulted in the effective disappearance of a tradition of public prayer in Lutheran areas in Germany. During the Further or Second Reformation in the seventeenth century in the Netherlands, the focus on personal practice of faith shifted to the family in a private setting.[1] This development in the Netherlands and Germany is thus rather different from England, where the Anglican Evensong was a reformation but adaption of the Roman Catholic Divine Office.

During the twentieth century, new impulses evolved from liturgical movements that aimed at awareness of the richness and possibilities in liturgy in the Protestant church. Since the introduction of a new psalter in 1968 and the hymnal Liedboek voor de Kerken in 1973, and the merger of most Protestant denominations into the Protestant Church in the Netherlands in 2004, new impulses in the domain of liturgy are notable. This is clearly illustrated by the Protestant Dienstboek (“Service Book”), which was in development since the 1990s. The Dienstboek has specific chapters on (evening) prayers, both in public and in private, that make recommendations on the structure of prayers, what psalms and hymns to sing, what lessons to read, and practical suggestions. The structure of a vesper will be discussed later in this chapter. First the role of music in vespers will be discussed.

Music in vespers

Evening prayers typically focus on thanksgiving, stillness and praying. The Dienstboek lists instrumental music as option to include in vespers.[2] It observes that organ music before Sunday services or during the collection often serves as background music rather than that it has a liturgical function. It emphasizes that music should make congregants aware of silence. Music can inspire and move, leaving a silence filled with meaningful tension. At the same time, music breaks through silence. The interplay between music and silence presents a particular setting that is open for one’s thoughts and emotions. So music, and for this research organ music in particular, can function well in vespers when it strengthens meditation, reflection and prayer through the interaction between silence and music.

In 2003, Peter Ouwerkerk wrote about the organ vespers as variant of the musical vespers. He mentions that an organ vespers is relatively easy to organize, for it only needs a church, organ, minister and organist.[3] He says that an added value of a musical vespers is that people might become more aware of the liturgical function of music in the regular service on Sunday morning. This effect of course can only exist when the people who participate in the vespers also join the service on Sunday. Then an interaction between participants and their notion and understanding of the music may take place. Ouwerkerk writes that the role of music in musical vespers is fulfilled by a preacher, choir or congregation in a regular service. Organ music thus has a connecting function in an organ vespers, and that makes that it is important to choose the music well. Appropriateness rather than the length of the music should guide the choice of music, and Ouwerkerk emphasizes that there should be a certain musical cohesion in the vespers. He suggests that the liturgy for an organ vespers can be thematically modelled, for example on basis of themes such as the Magnificat, a composer such as Johann Sebastian Bach, a poet like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, or hymns from a particular period. Non-liturgical organ works can be functional as well, because “each organ work becomes liturgical when it is placed in a liturgical context.”[4] Furthermore, non-liturgical music may create a wider variety of experiences and interpretations by participants in the vespers, while choral music often suggests a certain direction because of the texts or associations. Non-liturgical music is also fit to replace fixed parts of the liturgy as for example the Kyrie-prayer, confession of faith, prayers or even meditation. Ouwerkerk’s statement that music becomes liturgical in a liturgical context probably does not mean that everything is appropriate for a liturgical context. It does, however, underline that music that is not liturgical in nature can have a role in the liturgy, if carefully selected.

Two other remarks in Ouwerkerk’s article are worth mentioning. First, the author highlights that organ works are more effective when the use of organ is modest with congregational singing or just absent before and after the vespers. Second, hymn singing remains important in the vespers, for it brings rhythm in the celebration: it cause reaction and reflection. This research adds and argues that music is therefore the pre-eminent opportunity to let the congregation participate in the vespers.

Structure of a musical vespers

Ouwerkerk then refers to the Dienstboek and sees the prescribed formats for a regular vespers as a source of inspiration rather than as a fixed design. He analyses the formats as variants of seven fixed parts: invitatory, doxology, psalm, reading lesson, meditation, Magnificat, and prayers.[5] This largely corresponds to an article on the organ vespers in Het Orgel by Gerard M.I. Quaedvlieg some decades earlier.[6] Quaedvlieg refers to the Roman Catholic Liturgy of the Hours, and writes that the psalm prayer should consist of two psalms from the Old Testament and a hymn of praise from the New Testament, all preceded and followed by an antiphon. He takes the reading lesson and meditation together as one element, and adds blessing as then seventh component of the vespers. Quaedvlieg underlines that this structure should be recognizable in the design of an organ vespers.

The Dienstboek describes the order of evening prayers as follows. For daily prayers, psalms can be chosen from the psalm schedule, which assigns psalms to a particular day or time of a day just as the monastic traditions have schedules to read all psalms in one month. For less frequently held prayers, psalms can be selected that connect to the liturgical time of the year or the specific occasion. The same applies to the readings.[7] In a later, more elaborate explanation of vespers within the Protestant Church in the Netherlands, the listed structure is slightly different, for invitatory and doxology are taken together.[8] According to this publication the following structure can be distinguished (with the hymn and introduction to the reading as optional components):

Silence

Invitatory and doxology

Hymn

Psalm prayer

Introduction to the reading

Reading lesson

Moment of silence

Canticle

Prayers

Three practices compared

The listed structure in the Protestant Dienstboek remains valid in the Dutch practice in general. In The Netherlands, most organ vespers are held in (often historic) churches in city centres, such as/for example in the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, the Grote or Sint Laurenskerk in Rotterdam, the Grote or Sint Bavokerk in Haarlem, or the Martinikerk in Groningen. To get an impression of the liturgy of various organ vespers, the order of service of three different churches were studied.

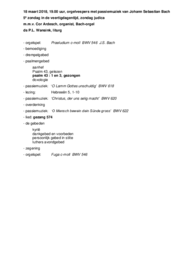

The first church is the interdenominational city church Laurenspastoraat in the Grote or Sint Laurenskerk in Rotterdam. This church organizes an alternation of Evensong, vespers and cantata services on Sundays at 7 pm. During periods as Lent or on fifth Sundays of the month, organ vespers are held. A comparison of several of those organ vespers held in 2018 and 2019 showed that they merely focus on the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

The second example concerns the Grote Kerk in Dordrecht. This church has two weekly vespers at 7 pm with a special musical accent, albeit organ vespers, other instruments, cantata services or sung vespers. The vespers are held in the Mariakoor, which is a part on the side of the church with the so-called “Bach-organ” in it, which makes it very fit for small-scale celebrations as vespers as well as musical prayers in particular. The organ repertoire is quite coherent, for example only Bach, only Sweelinck, or Krebs, Handel and Bach.

The third practice discussed stems from the Grote or Maria Magdalena Kerk in Goes. This church has series of vespers with a musical accent on Sundays 5 pm, including organ vespers, choir vespers, cantata vespers, abbey vespers and choral evensong. Over a series of vespers in the Advent period in 2018, each Sunday another verse of the same Advent hymn was sung, which adds to the coherence of the series.

From each of these churches, two or three orders of service were studied to examine the specific lliturgy. It should be noted that “silence”, which is the first element as mentioned in the Dienstboek, was not mentioned on the order of services of either of these churches, but it is most likely that there was silence before the vespers started with the organ prelude. In addition, most of the vespers were held in the periods of Advent or Lent, which typically do not have a doxology in the service. The table on the right shows a comparison of the three practices.

A comparing of these three organ vespers shows that the orders of service are quite similar. All three open and end with a moment of organ music, and have one or two interludes. The psalm singing or praying is essential for evening prayer, just as these are the heart of the Roman Catholic Liturgy of the Hours and the Anglican evensong. Indeed they appear in all three practices. Rotterdam includes both meditation and a moment of silence, Dordrecht only meditation and Goes only a moment of silence. All in all, the three practices provide concrete examples of organ vespers following the structure as outlined in the Dienstboek.

[1] Schuman, “Getijden,” pp. 136.

[2] Protestantse Kerk in Nederland, “Uitgangspunten en toelichting. Het dagelijks gebed: getijden en huisdiensten,” Dienstboek I (Zoetermeer: Uitgeverij Boekencentrum, 1998), pp. 1184-1185.

[3] The presence of a congregation or participants in the prayer is of course essential in a liturgy, but has no role in the organization of an evening prayer.

[4] Peter Ouwerkerk, “Orgelvespers: het orgel als voorganger,” Muziek & Liturgie, Volume 72, No. 10 (October 2003), freely translated by Iddo van der Giessen.

[5] Ibid., see also Protestantse Kerk in Nederland, “Het dagelijks gebed: getijden en huisdiensten,” in Dienstboek I (Zoetermeer: Uitgeverij Boekencentrum, 1998), pp. 955.

[6] Gerard M.I. Quaedvlieg, “De orgelvespers als liturgisch concert,” Het Orgel, Volume 86, No. 10 (October 1990).

[7] PKN, “Het dagelijks gebed,” pp. 956.

[8] PKN, “Uitgangspunten en toelichting,” pp. 1171.