Crossing Seven:

Can You Teach Me?

By Moira Hille, Annette Krauss, Ermyas Legesse, Shalom Lemma

Shalom Lemma: When we walked through the meda, children were playing there. I would like to investigate the meda a bit more.

Moira Hille: What kind of space is it? What do you know about medas?

Ermyas Legesse: In urban communities, we use the medas for playing soccer and shepherds take their cattle there to graze. Today, it’s rare that you find these large medas unless they are near a river, where people tend not to build as the soil is not so strong. You will see adults and kids playing soccer, kids running around. And you see a lot of nature. We just use them to play around.

SL: There are fewer and fewer medas in urban spaces, due to the boom in construction. The medas have been degraded and given over for other purposes.

EL: They are rare, but if you walk around a lot on foot, you will find them. Here the open spaces are not well taken care of, and nobody seems to pay attention.

AK: I have a map of Addis, and there are a lot of medas on it.

MH: This is actually funny because on my map of Addis there are hardly any medas.

AK: I identified a few. Two are just behind the school building. I saw them from the upper floor of the Alle School. People are hanging out, kids are playing soccer.

MH: Here on my map, there are only a few medas — it does not show a lot of green in the inner city.

AK: If you zoom in on this map, it says if it is a meda or not. I wonder who made this map.

EL: But you see, this meda, for example, is enclosed and nobody can get into it.

AK: Does this mean that it is not a meda at all? How do you read this map? Can you teach me?

MH: It would be interesting to go to these medas, look at them, and investigate further. It would be important to learn more about the relationship between communal spaces and the medas!

Crossing Six:

Buying and Selling

A Project by Tesfaye Bekele Beri

For Wax and Gold, a public art performance, I aimed to stimulate reflection on the condominium houses in Ethiopia. The performance took place on a public street, where I auctioned off scale models of the condominium houses to the public. The event took place at a time when the government began registrations for those spaces, so the mentality of selling and buying a space (especially condominium flats) was very present. People, the media, everybody were talking about condominium houses.

I built small models of condominium houses according to the four types the government provided. During the performance, people were very active. They raised questions and criticised the role of the government, they engaged in Addis’ public spaces and participated in discussion. They talked with each other about this current situation and there was a lot of bargaining, since some buyers resold their models. This process of buying and selling allowed for a broader discussion about events in Addis.

Tesfaye Bekele Beri, “Wax and Gold” Project, 2013, Addis Ababa. Photo: Tesfaye Bekele Beri. Courtesy of the artist.

Crossing Five:

Why Is It Done Like This?

By Vladimir Miller, Emnet Woubishet, Helen Zuru

Emnet Woubishet: The residents told us that they fenced off the compound with a wire-mesh fence about three months ago. They said that without a fence anyone can get in, and out and they wanted to protect their children.

Helen Zuru: It is not only that the parents were scared that somebody might come in from the outside, but also that animals and small children might get lost.

EW: Maybe they are also afraid that at night animals like hyenas come inside. The fence keeps animals out.

VM: Do any of these households keep cattle?

HZ: Hannah, one of the residents we spoke to said she just came back from feeding the sheep. [...] Hannah said it will take her time to get to know everybody around here and to engage in the Idir.

VM: Hannah mentioned that when the residents move in, they first complete the interior spaces, their own space. Now that two years have passed, most of the residents have finished working on their apartments and are now starting to take care of the communal spaces. This is why the fence only appears now. It took the residents two years to organise themselves in such a way that they could finance the fence collectively.

EW: Hannah also talked about the communal gardens: any of the residents can cultivate the small strips of land around the houses. Her father made the garden because he wanted to grow potatoes. Anybody can participate in gardening. It is done according to people’s interest and availability. Most people living here commute for work; they don’t have time for gardening. Hannah’s father stays at home; that is how he can do it.

VM: The gardens are placed in what seem to be leftover spaces — between the building and the outer fence in the corner. Wouldn’t it be more practical to use a part of the central space for gardening. Why is it done like this?

EW: When we asked the residents, they mentioned that the central space is reserved for the building up of tents for bigger communal events and activities — for example, in case of a funeral. It also functions as a playground for the children and as parking. The space in-between the wall and fence is more suitable for plants because they are more protected.

EW: The big plot of land, which is used for events like weddings and funerals, is also used to dry clothes. Clothes are mostly hand-washed and dried in the sun. The laundry line belongs to everyone. That is a commoning element.

VM: We also saw a herbal garden. One person did this, but everybody can pick fresh herbs there.

EW: Yes, herbs are used in small amounts, so everyone can take some. These plants are mostly used for medicinal purposes so everyone is invested in protecting them.

HZ: In my house, we have these types of plants a lot, and our neighbours knock and ask if they can pick a little if somebody is ill in their family.

VM: It seems we misunderstood the fences around the small garden in the beginning. The fences are actually a protection against animals and not necessarily an enclosure of communal space since, as you have explained, everybody is welcome to join in with the gardening.

Crossing Four:

Where Are We?

Reflections by Vladimir Miller and Anette Baldauf

We find ourselves in the middle of the vast grass meadow just behind the main road at Jemo Condominium Site. We look around. We are surrounded by a panorama of buildings, roads and yards. Buildings appear as standardised model houses, as though carefully placed in an architectural rendering. We study the panorama from a distance. A bull appears out of nowhere and we jump to run out of its way, thinking it might chase us. It is silly and funny and, afterwards, our laughter mixes with the shock of non-belonging still buzzing in our bodies.

On the meadow looking at the condominium blocks, the scene we find ourselves in is overdetermined and overwritten. The official narrative for this site is one of modernisation and the government’s aim to create adequate housing. But there are many other stories, some told in whispers, some discussed behind closed doors. Who lived on the land before the construction workers arrived? Whose cattle grazed here? Who collected firewood in that forest? How do we measure a city’s well-being when uprooting a life is a justified measure? And who are we to question motivations and desires for modernisation?

So we stand there, trying to observe and listen — but we cannot grasp what we see and hear. We cannot make sense of it. We don’t move because we don’t know which direction to take. Doing research is such a strange way to get to know a neighbourhood. We turn and only see ourselves: sticking out like sore thumbs, our presence is all too obvious. A group of mostly white researchers scrutinising, measuring, judging, dismissing, before finally returning to their comfort zone. Keeping a safe distance to the object of study, since, after all, it is far closer than it appears. The call for improvement, for change and development is an echo of well-known imperatives. We feel implicated, guilty by association in that mad improvement paradigm that the project of Western modernity let loose on the world. The housing blocks appear as foreign to the landscape as we are walking between them. So, what to do here in this kaleidoscope of global relations — this experimental laboratory of a utopian future and the past? Can we meet here and not do anything, or at least nothing productive? Can we simply watch and be aware of our lenses, listening and acknowledging sonic registers?

Spaces of Commoning research group, School of Commoning, 2015, Addis Ababa. Photo: Stefan Gruber. Courtesy of the artists.

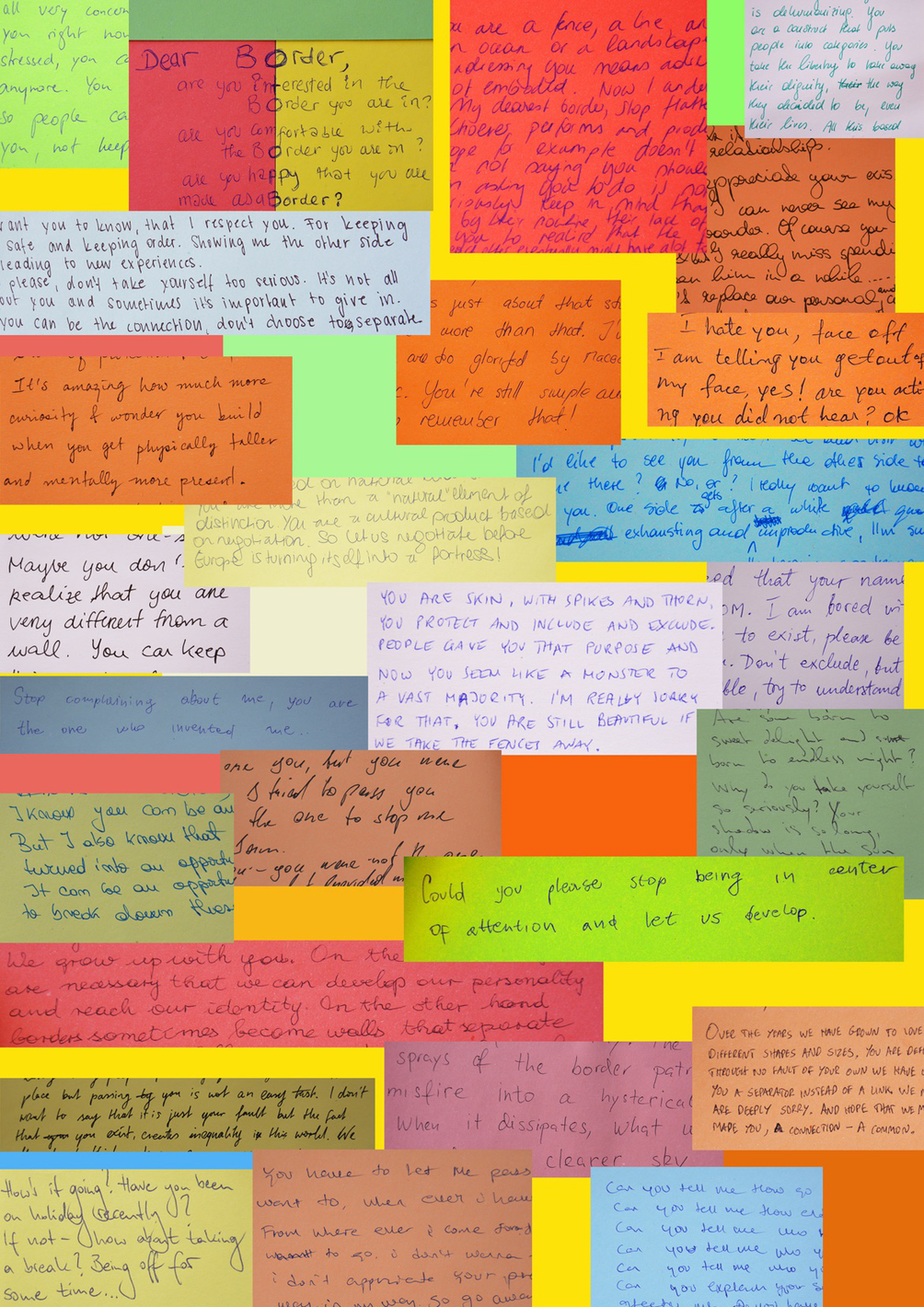

Dear Border,

Commoning Seminar, Forum Alpbach 2015

Participants of the Commoning Seminar, Forum Alpbach 2015, Poster. Courtesy of the artists.

Crossing Three:

From Miscommunication Station to Eight-Second Sonic Refuge

By Tesfaye Bekele Beri, Dawit Girma, Hong-Kai Wang, Mihret Kebede

There is a great gap between those who are free to speak and those who are governed into silence. Our bodies simply cannot cross that gap easily, and neither can our tongues. At Jemo Condominium Site II, we do a small exercise: we interview one another as if we were on a radio show, reflecting on our conversation with a family displaced from Piazza.

(A cell phone rings)

Tesfaye Bekele Beri: Mihret, we are in the second minibus.

Dawit Girma: Yes, the second minibus.

HKW: Do you want to talk about how the frequent relocations from one condominium site to another make it very difficult to build trust among neighbours?

DG: The problem with trust at this site is that people here come from different areas. They don’t know each other and even if there is an open space, it is not functioning. The person we talked with needs to reestablish his social life every time he moves. Mihret, do you want to comment on that?

Mihret Kebede: I don’t know what you are talking about.

DG: The lack of trust people have. For instance, how people don’t allow their children to live and play with the community.

MK: They have not known the neighbourhood for a long time. In their previous living situation, they had lived in a neighbourhood for a very long time so they knew they could trust each other. Here everybody is from a different place. People here have no idea who lives next to them.

TB: When you went inside his apartment, I stayed outside. Did you meet his children?

DG: Yes, he has two children.

HKW: We talked to one of them. The girl said she does not play with

the kids from the condominium block. She only plays with her little brother.

MK: Her dad doesn’t trust the neighbourhood enough to let her go outside. And there is no space to play. So he sends her to her grandmother’s house and his friends.

HKW: The daughter said that her schoolmates who live in Jemo I have more communal spaces.

TB: Why did he move to Jemo I from Jemo III?

MK: Because of the high rent.

We have called this constellation a miscommunication station: the politicians, who try to respond to the needs of the society operate top-down. From the outset, this fails to address what is needed on the ground. Yet most people are unable to freely complain and respond to this system. They prefer to be silent as they know the consequences of speaking out.

Caught between fear and desire to speak out, the Jenmo I residents we spoke with expressed discontent with this mode of research. This short conversation was brought to a halt, leading to very little overall benefit for the community. However, we were then engaged in an act of listening, aware that we had contributed to the atmosphere of fear.

We have attempted to sketch out an idea of freedom in the form of radio waves: an ‘eight-second sonic refuge’.

There is only one private radio station in Ethiopia. The rest are government-controlled in one way or another. Radiophonic expressions and transmissions are authorised by the ruling system that we live under. These governmental stations do not operate without restrictions. Journalists who work there have divulged to us that the stations play a trick with programmes that may brush up against any conceivably sensitive subject. They invented an ‘eight-second hold’ tactics during live broadcasts, whether it is an interview with someone influential or a call-in on community issues. They HOLD the transmission for eight seconds before it reaches the audience, so as to fool them into thinking that it is live. If one does the math, can you imagine how many of those eight seconds we have lost altogether? What kind of fragmented temporality are we forced to live in?

Now that we have come to ‘know of’ the particularities of radio — its temporalities, airwaves, sounds, voices and so on — that are lost in nowhere, we want to build an eight-second sonic refuge, where all can feel safe to speak and pronounce eight seconds of freedom.

Crossing Two:

How Do We Hear?

A Concern Raised by Hong-Kai Wang and Mihret Kebede

Listening is a way of studying together, without the pressure of preparing a speech or authorizing oneself. At the Jemo Condominium Site II, we take several silent walks in small groups and listen to what comes within earshot. In between the walks, we describe to one another what we have heard until we exhaust our responses. Later on, we do another listening exercise in small groups and try to strike up conversations with the residents of Jemo about their everyday life.

Inspired by sound art collective Ultra-red’s pedagogical work3, we do the listening exercises in a context that not everybody involved is familiar with. Some of us live in Addis Ababa and the others live in Europe. ‘What did you hear?’ we ask one another. There is the sound of wind rattling the shack; there is the sound of construction from afar; there is the sound of music playing from a stereo nearby; and there is also something that some of us cannot make out.

Is there a single listening moment for us to grasp? Perhaps, or perhaps not. The sounds come to us all at once from the environment, and in order to make sense of what we hear, we filter through our preconceptions.

We shape the listening process and presuppose what we hear when we talk with some of the Jemo residents. They complain a lot about the management and the infrastructure of the condominium. It appears that the needs of the community simply cannot be met by a top-down system.

It’s also important to stress how our seeing interrupts the listening process, as what we hear is given meaning by what we see in association. Listening happens within other processes.