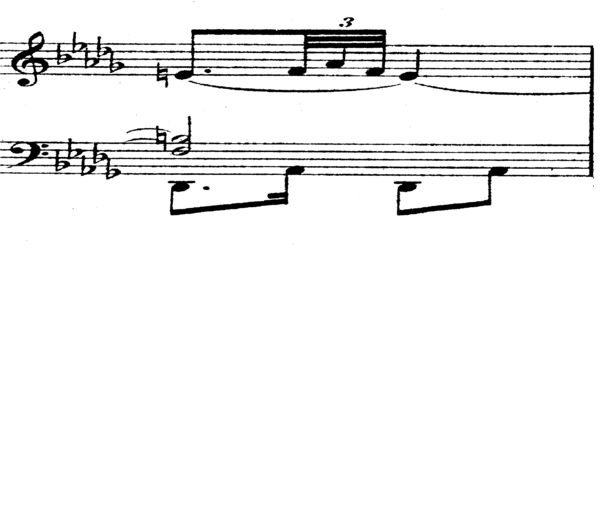

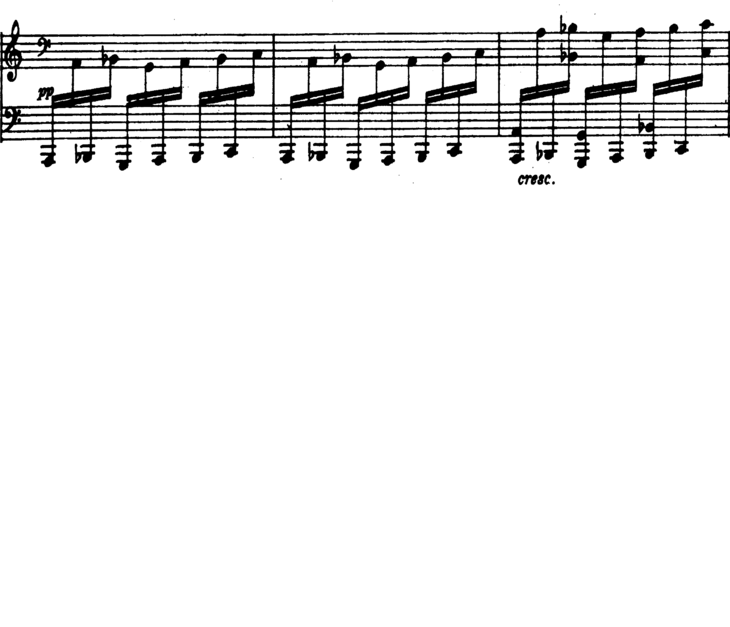

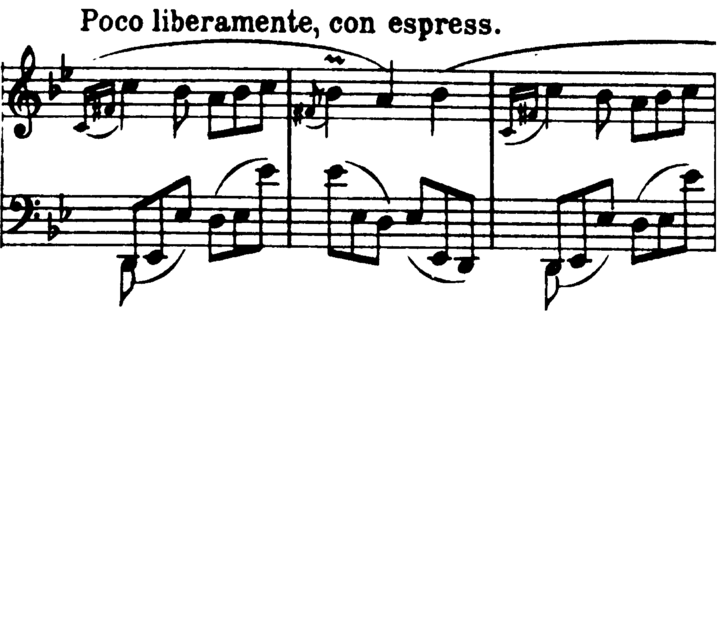

The same procedure is used by Falla in En los Jardines de la Sierra de Cordoba. In bar 41 (score example 17) he presents a copla passage played by the piano.

Later, in bar 186, the same copla is shown but, in this case, in other tonality and softer.

The passage of bar 186 might be played with much less expression and, taking into account Debussy´s ideas, the performer may imitate the “lointane” topic.

5. Debussy´s Spanish music

At the beginning of XX century, Spanish music was on fashion in Paris. It was possible due to the composition of pieces such as Geroges Bizet´s (1838-75) Carmen (1873-74) or Rimsky-Korsakov´s (1844-1904) Capricho Espagnol (1887). Furthermore, Albeniz and Granados, who obtained an enormous popularity in the capital, made the French composers aware of the real Spanish sonority. Being amazed by this new world of sound, Debussy composed many pieces inspired in instruments, styles and dances from Spain.

Through Debussy´s catalogue, several pieces directly inspired by Spanish music can be found:

- Lindaraja (for 2 pianos), 1901.

- La Soirée dans Granade (from Estampes), 1903.

- Sérénade Interrompue (from the first book of preludes), 1909-1910

- La Puerta del Vino (from the second book of preludes), 1911-1913

- Iberia (from Images pour Orquestre), 1905-1908

As it was already stated, Falla distinguished between flamenco and cante jondo. There is an obvious difference between Falla and Albeniz or Granados. Them (Albeniz and Granados) compose with evident Spanish sonorities and original folkloric songs, but Falla´s intention was to find the real primitive sonority from Andalucia. He expressed it in the article Our Music1.

As it will be proved, paradoxically, Debussy was closer to Falla´s conception than most of the Spanish composers. This statement is confirmed reading Falla´s article Debussy et le Spagne:

Taking all the above into account, an analyze of the most important pieces with Spanish inspiration from Claude Debussy and its relationship with Falla´s Nights in the Spanish Gardens will be done.

Lindaraja´s garden is a famous place in “La Alhambra”. Firstly, Debussy saw a postal in a French magazine and created the piece with that image in mind. It was composed in 1901 and was his first creation with Spanish inspiration. The rhythm used is “habanera” which was on fashion at the beginning of the XX century.

Despite of the connection with Spain, it should be noticed that Manuel de Falla does not use habanera rhythm in any part of Nights in the Spanish Gardens. As it was stated, the reason resides in Falla´s necessity of avoid dances that were link to Spain (also the Habanera is a rhythm from Cuba), but did not belong to cante jondo style. However, he uses the habanera rhythm in Debussy Homage (1920), due to the constant use of it from the French composer.

For the proposes of the present research, the most relevant passage of the piece appears in bar 31. Here, Debussy writes a figure that imitates a guitar arpeggio. This kind of texture was very popular at that time; evidence can be found in Albeniz´s or Granados pieces. However, the Spanish composers wrote them with regular figuration, while Debussy did it with odd groups, trying to find a closer sonority to guitar attack.

This sonority was, in fact, imperfect. Knowing it, Manuel de Falla admired Debussy´s ability to reproduce it in notated music.

As it was shown in the guitar chapter, Nights in the Spanish Gardens presents a passage with an “uncommon” figuration and evident guitar inspiration. It proves the presence of Debussy´s ideas in Falla´s piece.

La Soiree dans Granade represents the second piece of Debussy´s Estampes (1903). The basic rhythm is again “habanera” but as it was said, it is not taken by Falla in Nights in the Spanish Gardens.

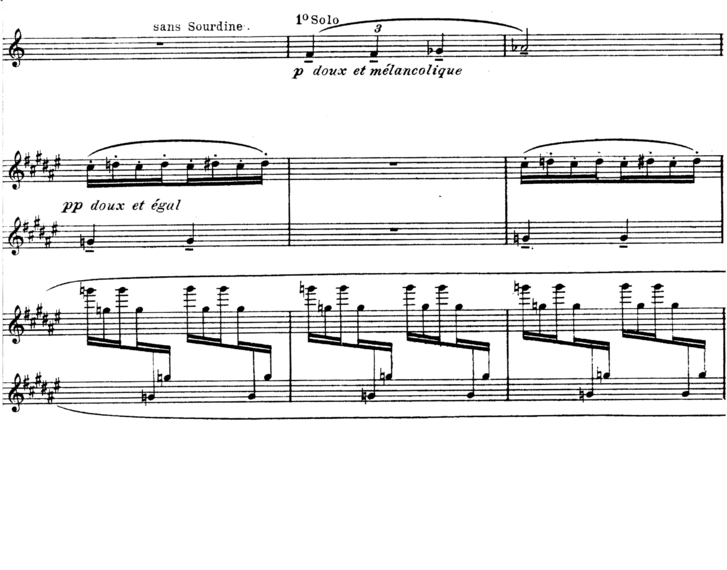

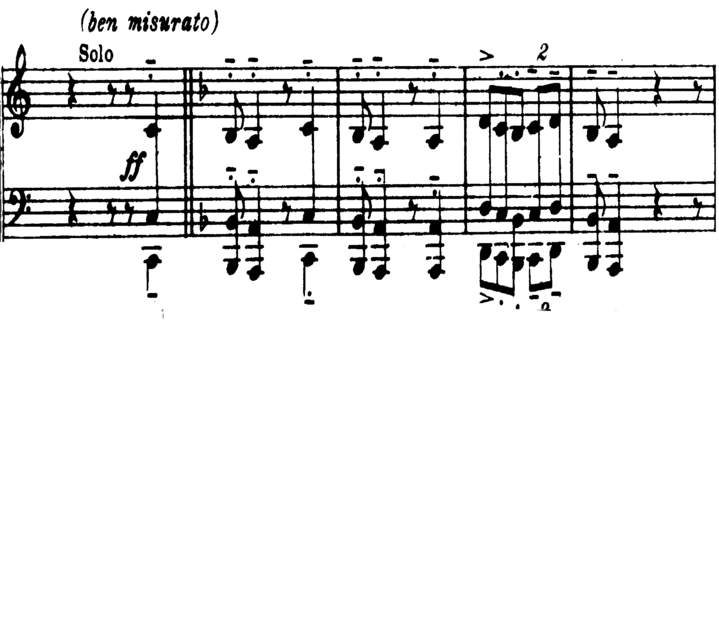

The most interesting parallelism appears in bar 7, where the first theme is presented. The similarity with Nights in the Spanish Gardens first piano solo is highly noticeable. It is based in the semitone and a very restrict range of notes. As it was said in cante jondo chapter, this semitone motive is used in order to imitate the microintervalic melodies of this particular style.

In Nights in the Spanish Gardens, the first appearance of the piano part develops this idea. As it was stated , several cante jondo features appear in this passage that may be performed consequently.

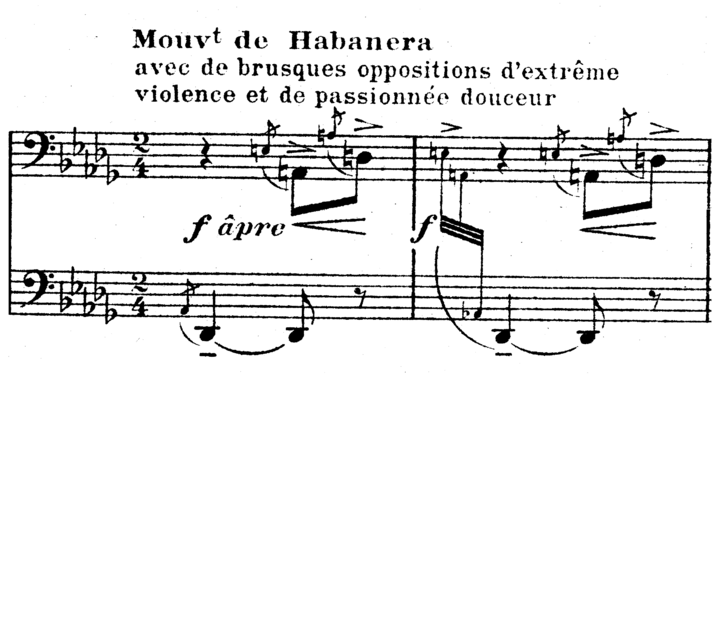

This is one of the pieces from Debussy´s second book of preludes. The name means “Door of the Wind” and was inspired by the famous door of “La Alhambra”. As it can be noticed, habanera rhythm is, again, present in the piece. The most important information appears at the beginning, where Debussy wrote “avec de brusques oppositions d´extréme violence et de passionée douceur” (with sudden oppositions of extreme violence and passionate sweetness). This violence and passion are, as it was analyzed, important features of cante jondo that evidence the inspiration of the piece.

This representation of traditional style is an obvious inspiration for Manuel de Falla, who wrote a highly similar passage in Nights in the Spanish Gardens. On it, as in Debussy´s piece, violent attacks in the piano bass register contrast with singing and melodic passages.

Therefore, all that sudden changes of character may be applied to the interpretation of Falla´s piece.

It is worth considering the importance of using a third instead of a second in the ornaments at bar 11 (score example 7). It is also used in other pieces such as La Sérénade Interrumpue and imitates cante jondo ornamentation. The same idea is used by Falla in Nights in the Spanish Gardens (bar 143 in score example 6) with the use of a diminished forth (f sharp-b flat). In this case, the final sonority is not the same but the concept of using a dissonant (in context) interval is, as it was said, imitating cante jondo sonority.

This shows a highly different conception of the Spanish music in comparison with Ravel or Albeniz; as it might be appreciated in this piece, this is true and deep Spanish sonority.

These turnarounds are present in passages of Nights in the Spanish gardens. Of course, it is not always clear if the instrument that inspires them is a guitar or human voice but, in those cases, the most important aspect is the melismatic nature of the ornament.

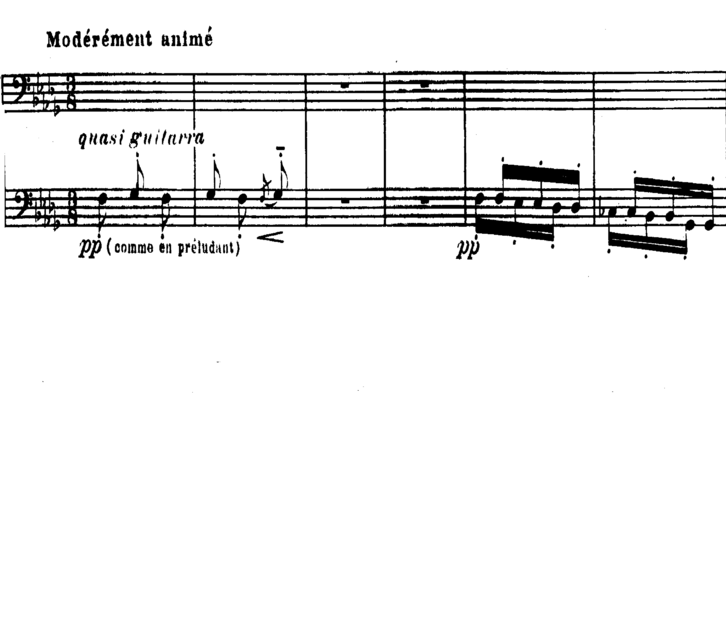

This composition appears in Debussy´s first book of preludes. The beginning of the piece presents two important marks that may be studied. The first one suggests “quasi guitarra” (almost like a guitar). This way of playing imitates the common oscillation of two fingers attacking the string of the guitar.

A very similar texture may be found in several passages of Nights in the Spanish Gardens. However, Falla does not specify that he is, in fact, imitating a guitar player. Hence, it might be played aiming to that sonority.

The clearest example of this technique appears in bar 172 of Danza Lejana (score example 10), where Falla uses the same texture than Debusssy. However, at the third bar, the composer starts to add octaves in order to improve the crescendo effect. Despite it, the guitar inspiration is highly evident.

The second indication of La Sérénade Interrumpue expresses “comme en preludant”, (like a prelude). This is a very common way to start a song in cante jondo. The guitar starts with a rubato tempo that creates the ambient and sonority to the singer; then, he/she pronounce two or three notes that are used to warm up and feel the tonality. It is usually performed crying “Ay”. After it, the singer starts the lyrics of the song. An example of it may be listen in audio example 7.

Thus, after guitar introduction, in bar 32 of La Sérénade Interrumpue the style of cante jondo is again represented using a semitone motive. As it was said, this would usually be sung mellismatically, crying “Ay”.

The same concept is undoubtedly used by Manuel de Falla at the beginning of Nights in the Spanish Gardens (score example 1 from cante jondo chapter). In order to understand it, it is important to read a letter written by Falla in 1916 to the conductor Ernest Ansermet. On it, the composer gives some advices to accomplish the performance of the piece. Talking about the beginning of the piece, he states:

As it was declared, after this beginning, the soloist imitates the “Ay” of the singer.

Taking everything into consideration, the inspiration of Debussy´s La Sérénade Interrumpue and the cante jondo style is obvious. Thus, soloist and conductor should aim to the “preludant” mood during the performance.

Iberia is the second of the three Images pour Oquestre (1905-13). It is reasonable to suppose that Manuel de Falla was aware of the composition process during his years in Paris.

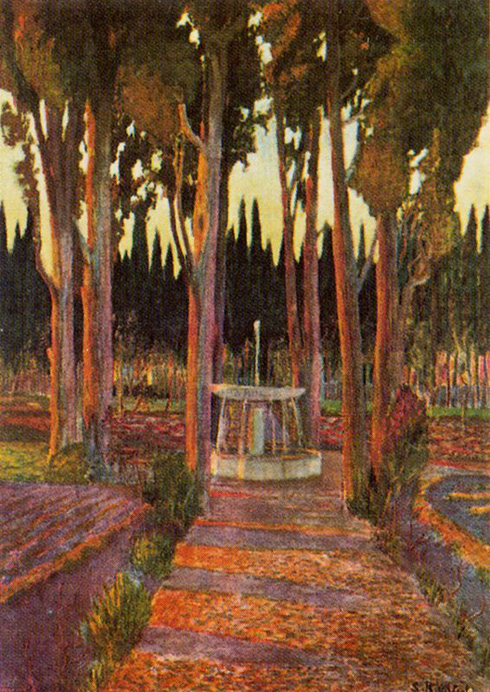

Iberia is separated in three movements: “Par les Rues et par les Chemins”, “Les Parfums de la Nuit" and “Le Matin d'un Jour de Fête”. Falla himself wrote about an image that could inspire Debussy to create the last movement of the piece:

Due to Falla´s knowledge of the piece and the similarities that will be exposed, his inspiration to the compositional process of Nights in the Spanish Gardens can be found in Iberia as well.

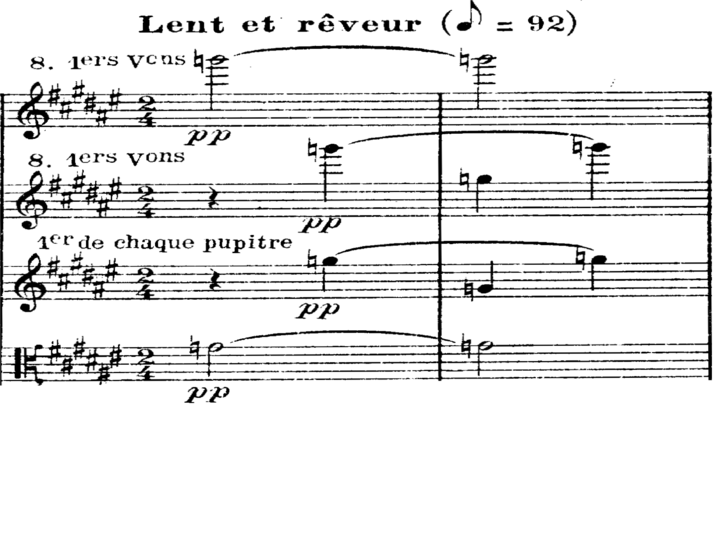

The first similarity appears at the end of the first movement. Here, the second theme of the movement is performed by the oboe; it is alternated with violin comments, playing sul ponticello. The melody is transposed and played in stretto while the orchestra keeps modulating, creating tension to reach the climax of the passage. It can be heard at audio example 6.

This procedure is the same used by Falla in bar 142 of Danza Lejana (audio example 7). Here, the melody is played by an oboe with the addition of the piano soloist; it is transposed in stretto and makes a big crescendo with violin interruptions.

As it can be appreciated in the examples, the global idea is greatly similar. A study of Debussy´s and Falla´s passages is highly recommended.

The second movement of Iberia starts with a very similar sonority to the passage of bar 167 in En el Generalife. In Debussy´s piece, a short range melody is played by an oboe with a mysterious mood in pianissimo; in the case of Falla is a bassoon; however, the final result is quite similar. They even use the same texture of the strings that play as accompaniment, which creates this mysterious sensation. It might be seen in “score example 11 and 12.

The title of the movement, Les Parfumes de la Nuit, is also related with night and mystery themes and may be inspiring for the performer as well.

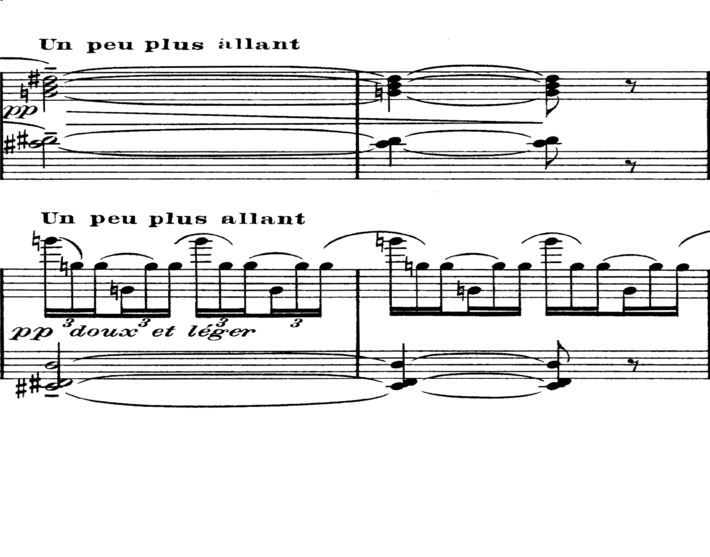

One of the clearest influences from the piece appears in bar 52 of Les Perfumes de la Nuit (score example 12). Here, music presents a dominant chord of C# with a minor 7th and 9th; although, the most relevant part is the addition of a diminished 5th played by the harp in 3 octaves, on top of this the woodwinds play a brief melody.

In score example 13, a version for 2 pianos has been added in order to clearly show the harmony of the passage.

Due to the “soloist” view of the piano part, the passage is usually performed with a big crescendo and almost fortissimo. However, having these similarities into account, it may be played “deux and leger” (sweet and light) as Debussy suggest to the harp player. The goal of the soloist and the orchestra should aim to create a mysterious sound between the different instruments of the passage.

As in Nights in the Spanish Gardens, Debussy´s piece presents a fortissimo and rubato climax after this passage. Play the previous part as dolce and leger as possible will increase the effect of that climax.

Impressionistic painters represent materials in different moments of the day, with different “light” in consequence. A clear example is the series of The Japanese Bridge (1920-22) painted by Claude Monnet (1840-1926).

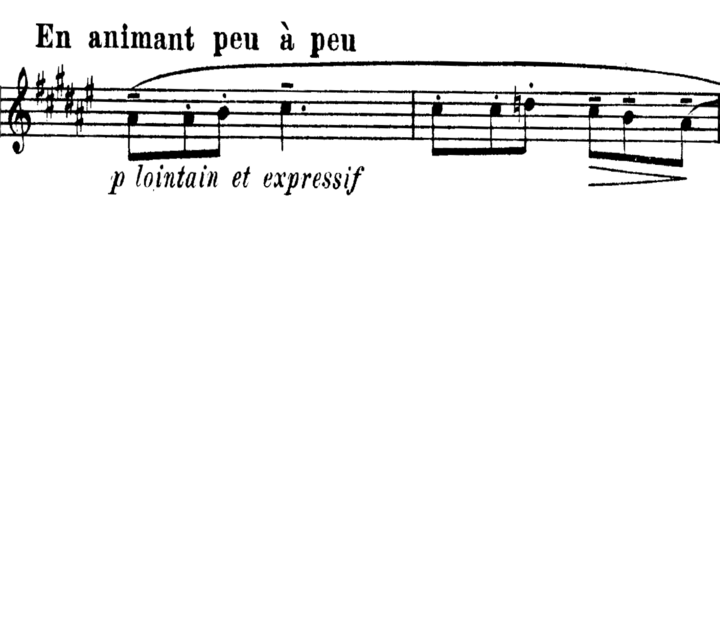

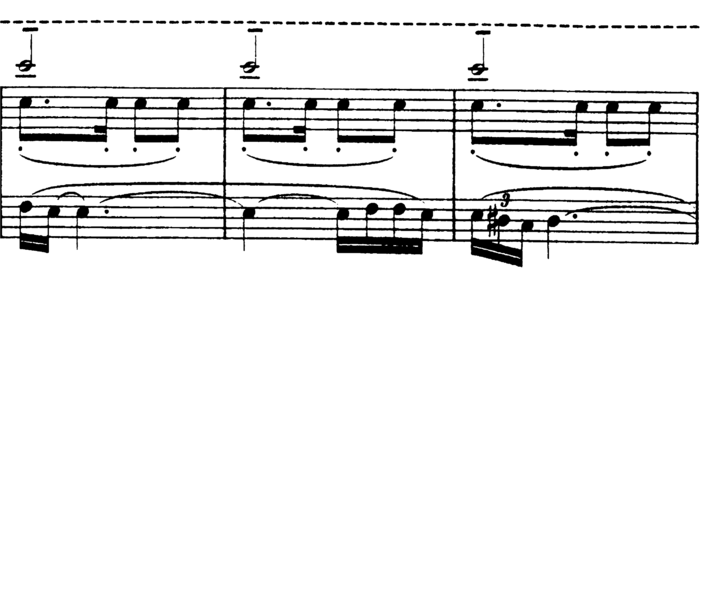

The same idea may be found in bar 124 (score example 15) of Les Perfums de la Nuit. This material is a “copla”, a Spanish typical singed form. It was frequently used by composers such as Albeniz and Granados and appears in the middle of numerous pieces.

The theme was already presented in bar 80, but piano and in an expressive manner (lointain et expressif); in the second appearance it can be found pianissimo and “deux et lointain”, creating a different ambient.

Let us now turn to folksong. Some consider that one of the means to “nationalize” our music is the strict use of popular material in a melodic way. In a general sense, I am afraid I do not agree, although in particular cases I think that procedure cannot be bettered. In popular song I think the spirit is more important than the letter. Rhythm, tonality and melodic intervals, which determine undulations and cadences, are the essential constituents of these songs. The people prove it themselves by infinitely varying the purely melodic lines of their songs. The rhythmic or melodic accompaniment is as important as the song itself. Inspiration, therefore, is to be found directly in the people, and those who do not see it so will only achieve a more or less ingenious imitation of what they originally set out to do2.

We are far from these Serenades, Madrilanos and boleros by which the makers of supposedly Spanish music formerly regaled us; here it is truly Andalusia that he presents to us3.

In "La soirée dans Granade" we could say that the singing is syllabic, while in “La puerta del vino” it is presented embellished with that typical ornaments from andalusian coplas that we call Cante jondo. The use of this procedure, also done in “serenade interrompue” is sketch out in the second theme of “danse profane”, this shows us what degree of knowledge of the most subtle variants of our popular songs had Debussy4.

But there is also an interesting fact about some harmonic phenomena that are produced in the particular sonorous world of the French master. These phenomena are done with the guitar in Andalucia in the most spontaneous way of the world. Curious thing: Spanish musicians have neglected, even despised, this effects, thinking of them as something barbarian or old; Claude Debussy has shown the way of use them5.

At the beginning, the melodic line “sur le pont”, and the arp near the wood, to imitate the sound of guitar6.

Just once (Debussy) travelled to Spain to stay some hours in San Sebastián and assist to a bull fight: it was just a little one. He kept, however, a very intense memory of the impression made by the unique light of the bull square: the amazing contrast of the part flooded by sun and the one covered by shadows. In “La Martin d´un Jour de Féte” of Iberia, it´s possible to find an evocation of that afternoon in threshold of Spain7.

Audio example 4: Falla, M. (1999). Nights in the Spanish Gardens. Arthur Rubinstein, piano. San Francisco shympony orchestra conducted by Enrique Jordá. The Rubinstein collection vol.32. RCA Red Seal.

Score example 6. Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. Third movement. mm. 109-113

Score example 10. Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. First movement mm 172

Audio example 7: La niña de los peines. Bulerias. Mirame a los ojos. Viajes a un corazón. Klamen records. 2013.

Audio example 9: Debussy, C. (1987). Images pour orchestra II, Iberia. London symphony orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado. Hamburg. Deutsche Grammophon.

Audio example 3. Debussy, C. (1994) preludes II, la puerta del vino. Christian Zimmerman, piano. Claude Debussy preludes. Hamburg. Deutsche grammophon.

Audio example 6: Falla, M. (1999). Nights in the Spanish Gardens. Arthur Rubinstein, piano. San Francisco shympony orchestra conducted by Enrique Jordá. The Rubinstein collection vol.32. RCA Red Seal.

Score example 12. Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. First movement. mm167

Audio example 11: Debussy, C. (1987) Images pour orchestra II, Iberia. London symphony orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado. Hamburg. Deutsche Grammophon.

Score example 14.Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. First movement. mm 117

Score example 15.Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. First movement. mm 41

Score example 16. Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. First movement. mm. 186

Audio example 5. Debussy, C. (1994). preludes II, la puerta del vino. Christian Zimmerman, piano. Claude Debussy preludes. Hamburg. Deutsche grammophon.

Audio example 7: Debussy, C. (1987). Images pour orchestra II, Iberia. London symphony orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado. Hamburg. Deutsche Grammophon.

Audio example 8:Falla, M. (1999). Nights in the Spanish Gardens. Arthur Rubinstein, piano. San Francisco shympony orchestra conducted by Enrique Jordá. The Rubinstein collection vol.32. RCA Red Seal.

Audio example 10: Falla, M. (1999). Nights in the Spanish Gardens. Arthur Rubinstein, piano. San Francisco shympony orchestra conducted by Enrique Jordá. The Rubinstein collection vol.32. RCA Red Seal.

Score example 12. Debussy, C. (1913). Images pour orchestre II, Iberia "Les parfums de la nuit".Paris. Durant et Cie. mm.52-54

Score exmple 13. Debussy, C. (1910) Images pour orchestre, 2 pianos version. Arranged by André Cpalet (1878-1925). Paris. Durand and Fils. mm. 52-53

Score example 15. Debussy, C. (1913). Images pour orchestre II, Iberia "Les parfums de la nuit". Paris. Durant et Cie. mm.80

Score example 16. Debussy, C. (1913). Images pour orchestre II, Iberia "Les parfums de la nuit". Paris. Durant et Cie. mm.124

Score example 4. Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. First movement. mm 25

Audio example 2: Falla, M. (1999). Nights in the Spanish Gardens. Arthur Rubinstein, piano. San Francisco shympony orchestra conducted by Enrique Jordá. The Rubinstein collection vol.32. RCA Red Seal.

Score example 7. Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. third movement mm 142

Score example 2:Falla, M. (1922). Nuits dans les jardins d´espagne. impresions symphoniques four piano et orchestre. Paris. Editions Max Eschig. First movement 18-19

Score example 3. Debussy, C. (1903). Estampes. La soirée dans Granade. Paris. Durand & Fils. mm. 7-9

Score example 9. Debussy, C. (1910). Preludes I, La serenee interrumpue.. Paris. Durand et Cie. mm. 1-6