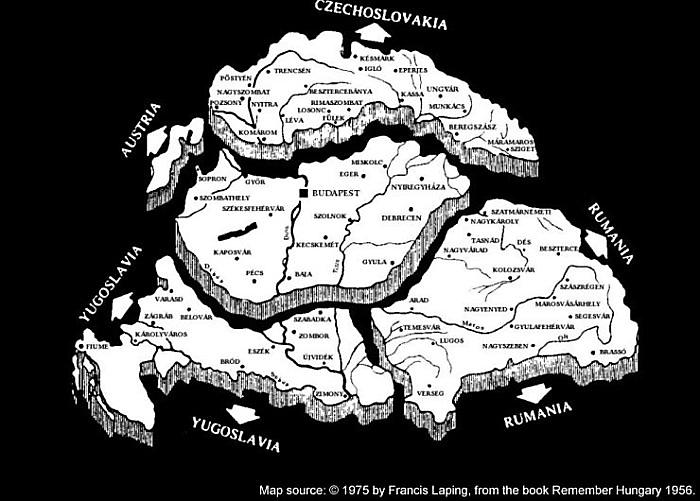

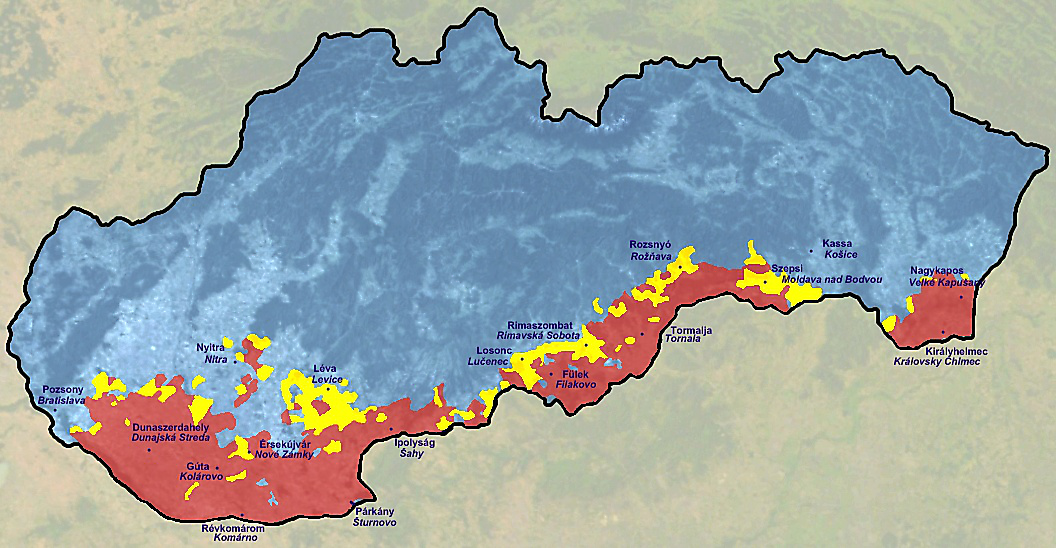

Let us look closely at the karaoke-apparatus employed by the curators and follow the history of the Slovak anthem in order to see how this differentiation operates within different spaces and times. The lyrics of the anthem, originally composed in the heyday of Central European national upheaval in 1844, call on Slovaks to stop lightning bolts over the Tatra Mountains. These bolts of lightning symbolize the enemy of the free Slovak state. This enemy – at the time of the song’s inception – would be decidedly (even if not explicitly) identified as the Hungarian Empire. However, during the times of the Czechoslovak republic, when the song became part of the national anthem, its Hungarian version was drafted and officially promoted among the Hungarian minority living in Czechoslovakia. This insistence on an equitable approach to minorities, intended to ease nationalist tensions, produced a rather contradictory situation where, by singing the state anthem, Czechoslovak Hungarians commemorated the national revival of Slovaks and their resistance to Hungarian rule. At the same time, its existence complicated the otherwise sanctioned ideology of Czechoslovakia as the nation-state of the two Slav nations explicitly articulated in its title. As for the contemporary staging of the Slovak-Hungarian anthem, it could be seen as a positive gesture embracing visions of ethnic plurality, yet ultimately it would serve as a provocation aimed at Slovak chauvinists, for whom the hybrid performance “defiled” Slovak national symbolism and promoted the revisionist politics of Great Hungary. As this short excursion into the past and present materialisations of the inter- or perhaps intra-national anthem demonstrates, performing it could produce multiple sets of differences, bringing forth different versions of national identities on an individual as well as macro-political level.

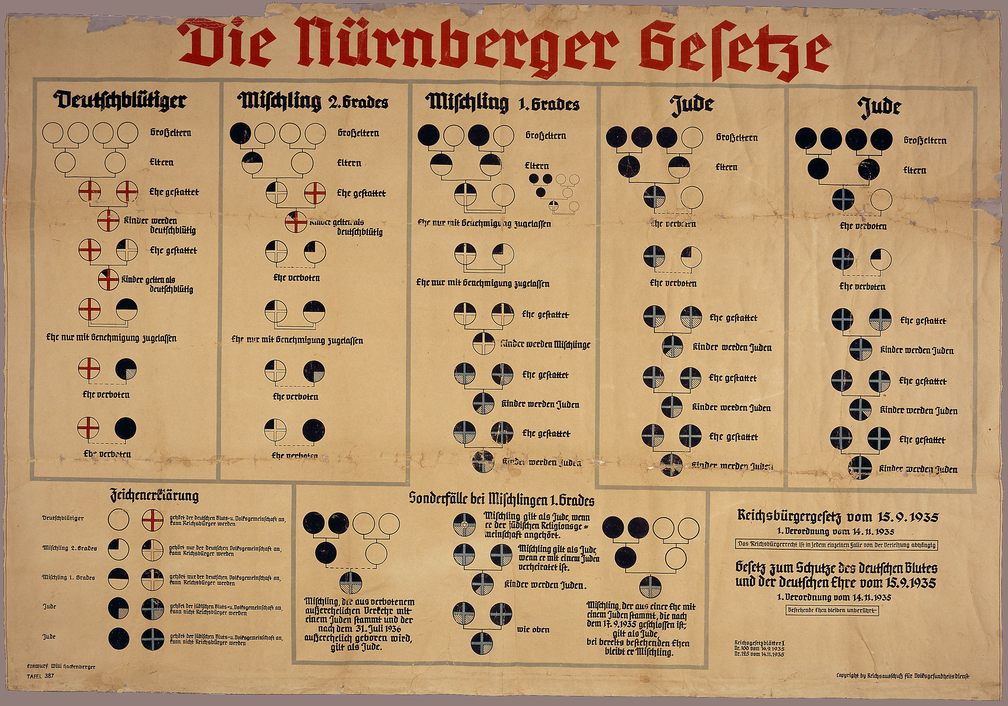

The resulting “national identity” is very different from the distinct, exclusive, and antagonistic notion preferred by politicians, who use differences between nationalities to pit people against each other, covering up differences within one particular nationality in order to produce a homogenous, monolithic identity on the one hand, while excluding whatever does not comply with its narrowly defined and fixed boundaries on the other. In this sense, we can see the radical political implications of the concept of intra-action. Given the current rise of xenophobia and aggressive nationalism(s) throughout Central and Eastern Europe, Barad’s ethico-onto-epistemology reveals the limits of a traditional essentialist approach to national identities and challenges the dangerous supremacist ideologies that stem from essentialism.

Personal post scriptum:

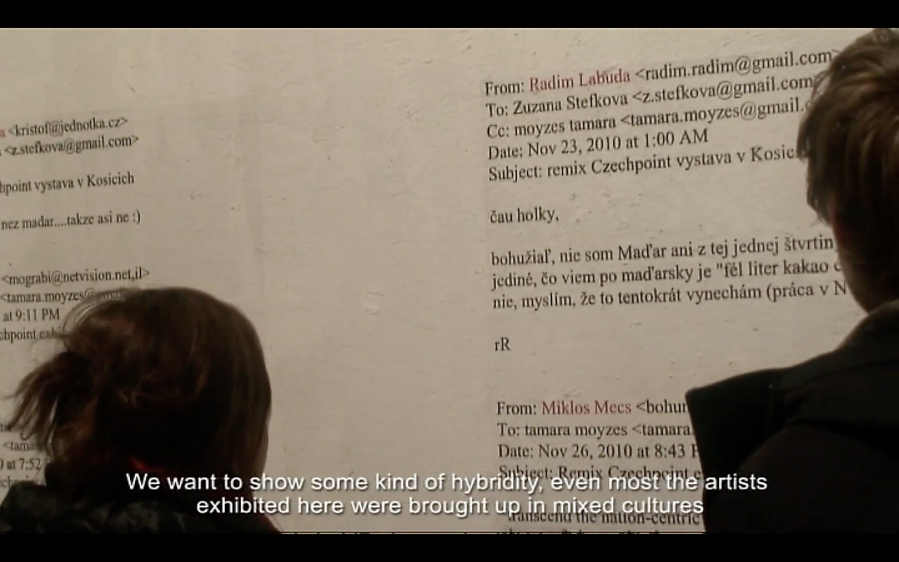

As we have already argued, the intra-active materialisations involved and transformed the curators among other “subjects”. That said, we should not imagine that simply by realising their performative gesture, the curators would emerge from the process displaying some brand new national identity; yet the experience of playing with and subverting of the notion of a fixed and distinctive national identity has left its mark. Out of the two curators, Tamara Moyzes continues strategically operating with her multiple national identities (she alternately performs her Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, Israeli, and Roma identity) in order to orchestrate and politicize differential patterns within her own identity. Štefková says that the silence after the Czech national anthem – where the Slovak part used to be before the split of Czechoslovakia – leaves her acutely aware of the missing yet present part of her own national identity. She always liked the Slovak part of the anthem more than the Czech one. It would not be overstating the matter to maintain that intra-action takes place within every creative enterprise. As Barad states in the introduction to Meeting the Universe Halfway when musing upon her own experience of writing: “It is not so much that I have written this book, as that it has written me. Or rather, ‘we’ have ‘intra-actively’ written each other.” (Barad 2007, ix) The same could be said about the process of curating.