TWO ROOMS AND A KITCHEN

14.1.2010

This morning, I turned the computer on before I took Elias to day care. The machine was rendering dissolves while I was pulling the sledge along Mechelininkatu Street. Before starting work, I also went to the shop. I bought buns, since my sound designer Tatu is visiting today. Together we look at images from my work-in-progress and plan the sound for them. The video’s working title is Two rooms and a kitchen.

It’s now ten thirty, I have one and a half hours before our appointment. I’ve put the washing machine on and lit the candles on the window sill. Both are rituals that I use to mark the start of the working day. The washing machine makes me feel efficient. The candles, in turn, mean something else. The element of danger associated with fire already creates a special mood. You have to concentrate on striking the match, you can’t do it carelessly or in a hurry. Above all, the candles are a way of demonstrating that, now, my time is my own. They turn the apartment with its two rooms and a kitchen into a workspace, into a place of contemplation.

That text is an excerpt from a diary that I kept in the spring of 2010, while I was editing the videowork Two rooms and a kitchen. The diary was part of a practicum in artistic research arranged by the Theatre Academy Helsinki on the topic of documentation. Within the course framework it would have been possible to choose some other mode of documentation – for instance, videoing – but I decided to try writing a diary, because it was sufficiently far from what I normally do. I had, in fact, never kept a work diary before. Nor was I particularly enthusiastic about the task, since I was afraid it would produce a Dear Diary -type sentimental text. This mental image bothered me at first, but, as the writing progressed, it was forgotten. On finishing the experiment three months later, I felt I had found a practical method that I could use in the future, too.

So, what was it that I found interesting in the work diary? First of all, it was amazing to notice how logically the text progressed – lots of things that ended up in the video were just germinating in the diary entries. At the same time, the writing showed the everyday concerns that give rise to my art. A good example of this is the washing machine mentioned in the first sample text, which I was in the habit of turning on at the start of the working day, and which ultimately became a key element in the video’s soundtrack. Most of all, however, I was fascinated by the immediacy of the text. The entries were made quickly, without any self-critique, and consequently they caught the freshness that is otherwise hard to capture. As I read the diary now in retrospect, it feels to me as if I were back at the editing desk, at the time when the work had yet to take shape, but all the possibilities were still open. At best it is possible to follow the working process, as it were, as a direct transmission, or with only a short delay, as in the following entry, which was written on the same day as the text at the beginning:

Time 15:37

Tatu just left. What a useful meeting! I realized the long dissolves do not work with the shots where there is movement. So, the structure of the work had to be redone: instead of dissolves it now mostly uses direct cuts. The long, slow transitions are reserved only for the bits where a lot of time – weeks or months – actually passes between shots.

The work feels more challenging now, since I have not tried out this sort of editing strategy before. But with regard to the sound, the task seems to be quite clear. In the images where there is action we use one-hundred-percent sound – i.e. the sounds recorded on the video tape in the shooting situation. In other pictures it is easy to insert various sounds that may possibly be heard in the apartment: the hum of the washing machine or microwave oven, the sounds of renovation carried in from the next apartment. Tatu promised to bang about with a hammer in his grandfather’s cellar and send the results for me to listen to.

I can’t wait to try out the new ideas. But, now, I have to go and collect Elias from the day-care centre and, before that, I have to hang up the washing. That’s been forgotten in the washing machine all day.

The aim of this essay is to give outside viewers, too, a chance to sit at the editing desk and observe a process that usually remains hidden. The text doesn’t include all my work-diary entries; I have selected only a few of them. Nor are the entries in chronological order, rather, I use them thematically. Some entries I have shortened, but I have not interfered with the sentence structures. In the second half of the essay I will additionally quote texts that viewers of my video Two rooms and a kitchen have written immediately after seeing the work. These texts have been produced at two artistic-research conferences, the first being the Nordic Summer University’s summer school in Kirkkonummi in July 2010, and the second the Colloquium on Artistic Research in Performing Arts held at the Theatre Academy Helsinki in January 2011. I am currently working on a new video based on these texts, which reflects the themes of Two rooms and a kitchen. Together these two works constitute a kind of diptych or two-part artwork. This essay is similarly divided into two parts or ‘tableaus’.

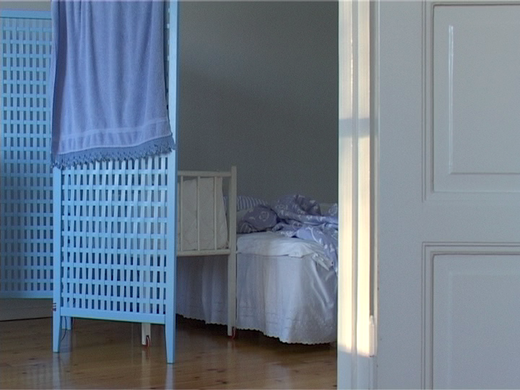

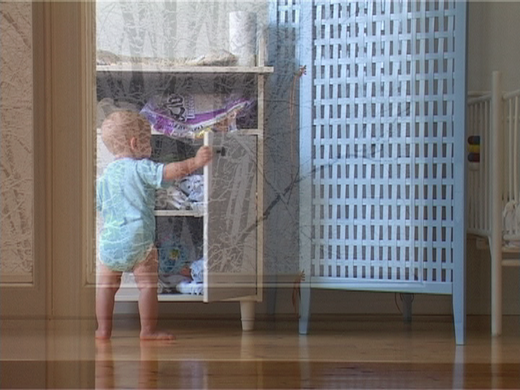

Apart from Two rooms and a kitchen, in my diary entries I talk about my son Elias, whose care sets the rhythm for my working day. Elias also appears in the images in the video, and he is thus interwoven in many ways as a part of my work. In fact, making my child a subject was one way of combining motherhood with being an artist at a time in my life when I had very little time to do my work. Another subject that came readily to hand was my home, where of necessity I spent a lot of time. To put it briefly, the video tells of a space formed by two rooms and a kitchen, and of a child who investigates that space. At the start, the child has just been born and, at the end, he is almost three years old, so his growth also makes the passage of time visible.

The essay on this page was originally published in a special issue on artistic research of the Finnish-language audiovisual-culture journal Lähikuva (3/2013). The videoworks were shown in the Studio at Kunsthalle Helsinki 28.4–3.6.2012. In the exhibition Two rooms and a kitchen (2010) was projected onto a wall, and Reflections in a window pane (2012) was shown on a screen fitted with headphones.

WORK DIARY OR AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH?

In my work diary there is an entry in which I consider the relationship between my chosen documentation method and autoethnographic research. The text goes as follows:

19.3.2010

A week has passed since I last made – or even thought about – the video. I was at a methodology seminar at the Finnish Metalworkers’ Union’s (!) education centre. At the start of the course, participants had to briefly outline their own research methods, and I said I kept a work diary. During the week, I learned that this can also be put another way. “I use autoethnographic methods” sounds a lot more impressive.

On the journey home Eija[1], Janne[2]and I chatted about whether we can really talk about the autoethnographic method with regard to artists. Eija thinks we can. Janne, in turn, asked whether we need such a concept. Isn’t it enough to rely on our own tradition? We can also ask how artists’ writing differs from autoethnography.

Autoethnography is an academic method that came out of ethnographic research. Underlying it is the insight that research focussed on ‘others’ cannot be transparent unless the researcher also includes her- or himself in it. In practice, she or he may make personal field notes or otherwise use writing to unpack her or his experiences.[3] I was drawn to autoethnography because it sounded more convincing than simply keeping a work diary. More broadly, this says something about the status of artistic research: we continually have to justify our work in relation to academic research, and to translate what we say into the language of science or scholarship. In the worst case we find ourselves seeking justification for artistic work in scientific concepts. At the end of my diary entry “Janne”, i.e. the Head of the Department of Postgraduate Studies at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts, asks whether we need the concept of autoethnography. So, is relying on our own tradition really not enough?

I agree that in artistic research there is reason to start off from art’s own methods. The artist’s work can be research without being scientific. But if we are still looking for points of comparison with the various sciences, the autoethnographic method is not one of the worst available. Artistic research and autoethnography are perhaps most clearly linked by the fact that the author uses her- or himself as ‘material’. Traditionally, in autoethnography (and art, too) choices have been directed at the major, dramatic life experiences. Nevertheless, alongside these the researcher Johanna Uotinen puts the “small autoethnography”, which focusses on everyday life and its almost invisible routines.[4] Uotinen gives as one example of an interesting subject the process of creating an artwork, about which the Australian Karen Scott-Hoy, for instance, has written in autoethnographic spirit.[5]

In Etnografia metodologiana. Lähtökohtana koulutuksen tutkimus [Ethnography as a methodology. Starting point: educational research] Ulla-Maija Salo mentions another feature that comes close to my own concerns. She says that many ethnographers have sought alternative, non-academic ways of writing. Salo even talks about aesthetic or artistic ethnography, in which research writing approaches literary expression. If the demand for scientificness feels worrisome, Salo urges us to view research as being like writing a letter or a diary.[6]

Despite the similarities, there is one major difference between me and a researcher who uses the autoethnographic method: the context, i.e. the setting or the frame of reference. My frame of reference is not situated in the realm of ethnographic research, but in that of art. Although the way that I do art has evident parallels with the autoethnographic approach: my works are autobiographical, I depict myself or my immediate circle, and I get my inspiration from everyday things. Where Uotinen speaks of “small autoethnography”, my work could be described as “small film”.

THE SMALL, PERSONAL FILM

31.3.2010

Help, I got another new idea for a video! It is related to Two rooms and a kitchen and already to its predecessor Room. The starting points for it are my experiences of visiting my parents’ apartment to water the plants when they are away. I am now thinking particularly of summertime, when my mother and father spend long periods at the cottage. A pile of post is waiting on the threshold. The plants have been gathered together on the kitchen table, on which a message has usually also been left for me. I have been collecting those slips of paper for years now, and some of them become the opening words of my video. Otherwise, the work consists of views into the empty apartment. The atmosphere is both homely and uninhabited. The blinds have been let down, and a sheet may have been spread over a sofa or armchair to prevent the fabric from fading.

I could film the work next summer when my mother and father leave for the countryside. The sun shines into the apartment for most of the day, so the light is not a problem. This time, I would like to create the impression that the images have been shot all in one go, on the same visit. The time spanned by the work would thus be different from the two previous works, in which days or weeks pass between shots.

I have already been to look for suitable slips of paper, and here are a couple of examples:

“Elina. Macaroni cheese. Ice cream in freezer for afters. Best, Mum”

“Elina. Could you close the window. Best, Mum”

“Elina. Eat what you like. In fridge for you: yoghurt, milk, some meatballs. Take the fruit home with you. By the way, I think you need a coat and a decent backpack for ‘job’ interviews. Otherwise, you lack credibility, that’s just how it is! Best, Mum”

Due to shortage of time, I didn’t film the above-mentioned work in the summer of 2010, and it’s possible I will never make it. Nevertheless, I wanted to mention this diary entry, since it says something about how my works get their beginnings, how I gather materials, and how the autobiographical ingredients – in this case the slips of paper left by my mother – are transformed into a “small film”. In the sample texts I am also in a different role than in Two rooms and a kitchen: this time, I am not an artist-mother filming her child, but a daughter whose own mother is worried about her credibility.

Letters and messages scrawled on slips of paper already played the main role in my videowork Pure, which was completed in 2002. Its starting point was some letters from 1942–1990 found in my parents’ loft. At the same time, this was my first videowork, and it was through this process that I learned the language of the moving image. That learning took place in the USA, at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where there was a strong tradition of experimental film. Nowadays, I don’t see myself as particularly committed to this, but my time in Chicago left its mark on me. Above all, I developed a specific kind of relationship with my medium: I see film as a personal means of expression, like a pen or a brush. As well as “small film”, what I do could be described by the term “personal film”, which, for instance, the Swedish filmmaker Gunvor Nelson prefers in place of “experimental film”. “Experimental films sounds like something incomplete,” Nelson says. “I have made both surrealistic and expressionistic films, but I think I prefer the term ‘personal film’. That is what it is about. Even if many don’t understand the meaning of the term.”[7]

The concept of film that I internalized also includes a certain handicraft quality. In Chicago I shot on 16mm film, and I used an old, hand-cranked camera that ran for only 30 seconds at a time. I transferred the material to videotape to do the editing, but I learned to approach every take with great care. I also learned to do all the stages of the work myself. Nowadays, I use digital video and collaborate with a sound designer and a graphic designer, but I still want to keep my projects small-scale. The concept of the “small film” thus refers not only to the subjects of my works, but also to the way they are realized. Even in the screenings I prefer the small scale: the ideal is for my works to be watched at home on the viewer’s own screen.

Having said that, I have to add that there is, of course, no reason why my works could not simply be called videos – which is, in fact, what I usually do. As the British film researcher Peter Wollen has said, film and video are not essentially different, since they are both time-based media. True, video tempts us to deal with time in a slightly different way from film: using a video camera, it is easy to shoot long, continuous takes, while time in film is often more fragmentary, interrupted by edits. But the difference is still small, and digitality dispels it even further. According to Wollen, video and film can be compared to two different drawing implements – for instance, to charcoal and pencil. Both produce a drawing, even if they represent different “technologies”.[8]

THE MIRACLE OF IMAGE AND SOUND

Having provided this background information, it is time to return to my work diary and to the space consisting of the two rooms and the kitchen. On the previous occasion, I had just met my sound designer Tatu Virtamo and realized that long dissolves do not work when there is action in the image. The following entry was made the following day:

15.1.2010

I have a few minutes to write. I set about re-constructing the work right from the start today. There are some gems among the material, whose value I had not noticed before. Certain pictures do not really look like anything on their own, but when they are combined with others, the whole thing works. Fortunately I have filmed so many of the ‘same’ scenes. Now, there are plenty to choose from. Even if there never seem to be enough details and stills. On the other hand, I can film more of them, for example, chair legs. I like these because they evoke the child’s perspective.

I also realized that I have to think about the sound at the same time as the image. I tried ‘stretching’ the soundtrack of some of the images over other images, and I noticed how sound creates continuity. The illusion of things happening at the same time in the same place does not come about solely from direct cuts, but above all from sounds that carry on from one picture to another. It is also possible to play about with this. I can edit the work as if the events were simultaneous. At some point, the viewer simply realizes that the child has changed and looks totally different, he has grown.

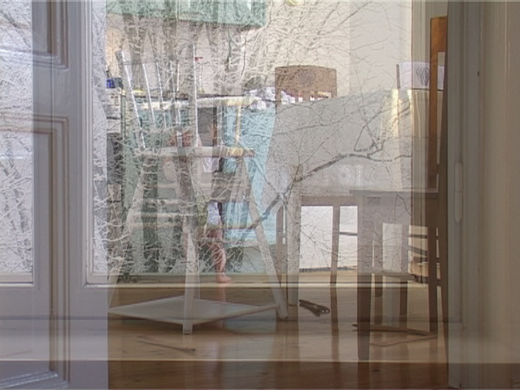

In film language dissolves have traditionally been used to signify the passage of time, and I, too, ended up using them that way in Two rooms and a kitchen. But this was not something self-evident, since a dissolve also has another attribute: it appears to multiply the space. I had used dissolves like that in my previous work, Room (2008), which had a slow, 14-second transition between each shot. This created the impression that the images, as it were, arose one out of another, and the room space became more abstract.

Experiencing a dissolve as something sculptural, spatial, seems to depend on the duration of the transition. When the transition from one shot to another is long enough, the image is constructed before our eyes, gradually, a layer at a time. That experience has something miraculous about it. For me, it brings to mind the way that, years ago, I used to develop black-and-white photographs in a laboratory, and watch how the image appeared on the paper in the developing bath. The dark areas emerged first, and, for a moment, an object or detail might be seen in the image that, later on, was obscured in shadow.

Another ‘miracle’ is what happens when we add sound to a mute image. In the diary entry above, this happens by stretching the soundtrack for the preceding shot, and then, later on, by adding the whirr of the washing machine in the background to the image:

12.4.2010

I tried out what the home-appliance recordings that Tatu had made felt like together with the images. Tremendous! Especially the sound of the washing machine is great, it has a calming rhythm, and you can even hear the water splashing.

One observation: when you combine the sound of a washing machine with a picture of a newly born baby, you immediately get the impression that the child is listening to the sound. His facial expressions and movements seem to be reactions to the sound. The sound seems to wake him up and make him open his eyes. When, a little later on, he wrinkles his brow and shuts his eyes again, it feels like the sound is disturbing him. There is a marked difference from a mute image.

I remember that ‘miracle’ already from the time of my first videowork, Pure. When this happened, I was sitting in the editing studio looking at a shot in which a stern-looking face was staring at me. The face did nothing other than raise its eyebrows slightly or twitch its lips. Then I put the voice-over of a man reading a letter on top of the image. Suddenly, the face seemed to be listening, every quiver it made looked like a response to what the man was saying. This was the initial impulse that got me interested in the interaction between image and sound. In that sense it was also when my research began to take shape.

Before I go on, it is perhaps worth reiterating how I understand the Finnish word tutkimus [usually translated as “research”] in art. If I were writing in English, I would not say “research” here, but “investigation”, “exploration” or “study”. That last word particularly appeals to me, because it brings to mind the old-fashioned model drawings and other studies that artists used to make. Thus, the idea of exploration has always been part of art. When I position my video camera on the tripod and stop to observe the movement of the sun, I am systematically studying the light. When, after filming, I transfer the material to the computer, name and index the shots, and then put them in chronological order, I am acting equally systematically. At this stage, themes, subjects or questions begin to stand out from the footage. In the language of science, the work begins to pose ‘research questions’ for me. That term is in quotation marks because I still find it somewhat alien – after several years of doctoral studies. It might perhaps be better to talk about different ‘working questions’ in the same way as we talk about working titles. Sometimes, the working title is kept as the final title – as with Two rooms and a kitchen – sometimes, it is replaced by another word or phrase later on. Work questions are thus kinds of engines that drive the work forwards, but which may change along the way. And yet, the texts that I write about my works seem to be linked by one common question: How have my works come about? What is the process of making an artwork like?

WINDOW AS A TIMEFRAME

The first question that Two rooms and a kitchen posed for me was about the sheer volume of material. I had spent three years filming the work, and dozens of hours of videotape had accumulated. Sometimes, I had filmed almost every day, at other times, with a break of a few months in between. How was I to combine shots taken at different times? In the following diary entry I outline one possible solution:

25.1.2010

Monday. An amazingly relaxed weekend behind me, Elias slept for three hours on his daytime nap, and I was able to get all my ‘homework’ and other paperwork out of the way. Now, I can spend the whole day with the images.

On the way to work (i.e. back home) I was thinking about the structure of the work. The problem is still that the shots have been filmed at different times, in different lighting conditions, and combining them using direct cuts is not easy. Yesterday, I decided to temporarily leave black frames at the difficult points. From that it occurred to me to wonder whether those black sections – visual pauses – could be an editing strategy? What if I were to construct the work so that it consisted of short fragments of a few images, with a blank between them? The images would, as it were, be views of life lived, the things picked out by memory.

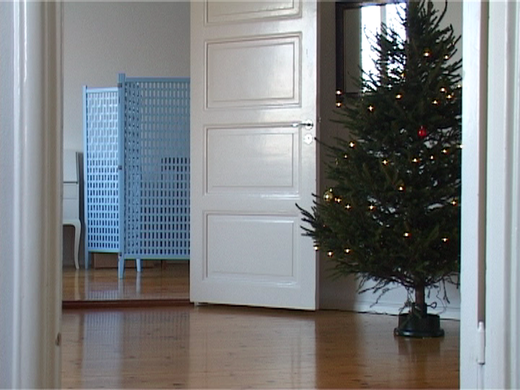

In the finished work, however, the place of the black frames has been taken by a window outside of which snow is falling. The framing of this window is always the same; this consists of a single, continuous take, out of which I have chosen a passage about fourteen minutes long. The only change that occurs in the image is that the snowfall occasionally gets heavier. Along with this, the landscape seen from the window – the tree and the roof of the building opposite – becomes increasingly white.

The transition from the window to the apartment interiors always occurs via a 12-second dissolve. In the middle of the dissolve – when the two images can be seen through each other – it looks for a moment like the indoor space is reflected in the window pane. That is how I, at least, experienced it when I was editing the work. This may come from my habit of looking at images in slow motion or freeze-frame, which leaves more time to inspect the individual view. In any case, the transition through the window reinforced the idea mentioned in the diary, that the interior images of the apartment are memories. The work thus got two time levels, with the window representing the present moment and the interior images the past.

In the history of visual art the window is, of course, a much-used metaphor. In The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft Anne Friedberg goes through its various meanings. For a start, the window has been a “window on the world”, an aperture from which we observe something. Such windows are often unglazed, there is no blurring or reflecting glass in between. But if the window is closed off, apart from being an aperture, it acts as a reflective surface or mirror. At the same time, a closed window is always a wall between outer and inner space. Added to that, the window’s crossbars form a frame that marks out the edges of the view. Nowadays, the metaphor is reproduced on the computer screen, in which we open “windows” one after another. Even Microsoft’s operating system took its name from the window.[9]

In Two rooms and a kitchen the window also has an aural counterpart: the whirr of the washing machine. This, too, advances in the present moment, beginning with the opening credits and ending just as the last closing credits fade. If we are to be precise, the sound of the washing machine is not heard absolutely the whole time, but only comes to the fore at certain points. Nevertheless, the effect is of the work spanning an entire washing cycle, including the spin. The graphic designer Jorma Hinkka pointed out that a suitable title for the video would have been Delicate wash 40 degrees. Hinkka’s quip came to mind again when I was thinking about a title for this essay, and I made it the heading for the text. I like such concrete, unpoetic titles.

Jan Kaila also made an apt observation after I had shown the video in the Department of Postgraduate Studies at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts in May, 2011. He said that in the work the whirr of the washing machine acts like background music. It creates another level in the narrative, and we don’t know whether that level belongs in the world of the film, or comes from outside it.

SNOW IN AN HOURGLASS

With the window I had solved the issue of how to connect the different episodes together. I was also pleased when I found a natural way of using dissolves. But the snow falling onto the interiors evoked a new association that I did not like. This is described in the next quotation:

22.3.2010

I just tried out having the window constantly visible beneath the other images. That doesn’t work. What is interesting is specifically not the overlapping of the images in itself, but the change. During the slowly shifting dissolves, the view is constantly changing. The room space appears in the window pane. Natural light starts to come into the dark corridor. The sleeping child is covered by falling snow.

I was left wondering about the phrase: “The sleeping child is covered by falling snow.” It reminds me of death. What on earth do I do about that? I don’t want the viewer to think that the work tells of a child’s death. If the falling snow is further combined with a candle, danger is close. It is really significant where I put the candle. Not at the end, anyway. In contrast, the last sleep shot is quite good. In it our attention is focussed on the child’s breathing. The bare stomach rising and falling.

Later on that same day – at 11:54 – I ask:

Or does falling snow necessarily refer to death? Could it be interpreted more broadly as an image of time, remembering and disappearance? The snow falls as if onto the events. It covers them over, beneath it. Encloses things within it. Like a blanket.

To avoid the association with death, the candle was ultimately left out of the work, along with many other beautiful images that felt superfluous. Just to make sure, the sound of the child’s breathing was also turned up to an audible volume at the end – as if to prove that life goes on. After that, the snow could fall onto the images in peace. At one point, it even seemed to form a permanent blanket of snow. That point is in the second half of the work, which was shot while the apartment was undergoing radical repairs, having all the water piping replaced. In the first phase of the renovation, the apartment is uninhabited and covered in plaster dust. In the second phase, the space has been cleaned and the furniture is in place, but covered by a thin protective plastic that is reminiscent of snow or ice. The whole apartment looks like it is in hibernation. This is further accentuated by the way that, in the following episode, there is a Christmas tree standing in the middle of the apartment, its branches merging with the snowy branches of the tree seen out of the window. It feels as if the boundary between outside and inside formed by the window has been obliterated, and winter has forced its way in.

Subsequently, the snowfall has also brought to mind the grainy, scratched surface of film. I have nothing against this association, on the contrary: I like the way the fluttering of the flakes blurs the sharpness of the digital video. But an exquisite interpretation of the snow has been put forward by the Danish performance artist Ellen Friis, who saw my then-unfinished work at the NSU’s summer school in July 2010. According to Friis the window in Two rooms and a kitchen acts like an hourglass, which measures cyclic or ‘eternal’ time. The snow falling outside the window is thus like the sand in an hourglass.

THE DOORS OF THE UNIVERSE

19.4.2010

Monday. This morning, the following conversation took place at my worktable:

WOMAN

Hey, I want to show you a clip. Isn’t it great?

MAN

A romanticized depiction of family life.

WOMAN

This has nothing to do with family life. It depicts how a child explores space.

MAN

Well, it is pretty great. I’m still wondering how you’re going to bring out that exploration. I think it comes from repetition. From the way the child tries first one door and then another.

WOMAN

Right, he’s systematic.

MAN

If he only tried one, it wouldn’t yet look like research.

WOMAN

Look, you’re in this, too. Or your socks are.

MAN

Oh, there’s that shirt.

That entry is one of my favourites in the work diary. First, the text briefly indicates what I think the work is NOT about (family life) and what it IS about (a child exploring space). Secondly, the style of the dialogue makes me smile. It is light and a bit bantering, yet at the same time, the speakers define the concept of research.

The sequence referred to in the dialogue is in the middle of the work. It starts with a view into the kitchen, where the child is investigating the cupboards. Later on, he moves into the adjacent room and, finally, into the bedroom. In the middle space the sound of a television programme can be heard in the background. “A tiny, infinitely dense point expanded with immense force,” the programme’s narrator says. “That is how the universe and all that is in it, including time, was born.” The voice is the classic “Voice of God,” a deep, male voice that is associated with objectivity and trustworthiness.

The television programme was captured on the video by chance, but I could not have got a better voice-over for my work. That respect-inducing tone gives an appropriate gravity to the child’s actions. The words “universe” and “time”, in turn, emphasize the themes of the video – after all, the childhood home is “our first universe”, “a real cosmos in every sense of the word” as the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard says.[10]

Bachelard also says that “our first universe” is physically inscribed in us: after twenty years, we are able to walk up the first stairway of our childhood home and not stumble, and “The feel of the tiniest latch has remained in our hands”.[11] We might point out to Bachelard that the feel of the latch remains not only in our fingers, but also on our tongue or teeth. At least in my video the child explores the doorways of the cosmos not only with his hands, but with his whole body. In one of the most fascinating scenes he stops to ‘play’ a squeaking hinge. In everyday life such behaviour easily strikes us as annoying, but the video image reveals that it involves intense concentration. Perhaps this could be considered to be one of the work’s ‘finds’ in a human or cognitive sense? In art these finds are more often linked to the form of the work. They might, for instance, be apt metaphors or structures – such as windows or washing machines. Sometimes, the greatest find is a new viewpoint. This happened, for example, when I began hearing the child’s vocalizations as his own distinct language.

“MITÄ PATUTTUU?”

25.3.2010

The end needs rethinking. Or in more detail. Up to the Christmas shots, the editing works, the framings are sufficiently different and each fragment justifies its place. But after that, there are lots of similar views. In each one the camera is more or less in the same place and you can see the kitchen in the background. In one of the shots the child is building a Lego tower, in another he is playing “kateboarding”. In two images we see a red tractor. In one quite amusing shot the child is putting on his trousers while singing: “Lovely, lovely…” Until the song turns to moaning when both legs go into the same trouser leg. All the images are in principle good, so it’s hard to give up any one of them. But what is essential here in terms of the whole? Do we need both the Lego and the tractor? What do they tell us?

I try to keep the title of the work in mind. Two rooms and a kitchen. So, the centre of gravity is in the space. The red tractor is interesting, since it is unreasonably large for the small apartment. The Lego house, for its part, is interesting, because it is about building things. There is also a beautiful light in the picture, and it is easy to combine it with another shot in which the child is pouring water into a jug. The trousers have nothing to do with the space, but the shot is rare in its spontaneity.

There’s nothing for it, but to try things out. How would I do the end if I cut it with a ‘heavy hand’?

The trousers, water jug and tractor were ultimately left out of the work, but the Legos stayed in. In the first Lego shot the child is building a tower out of bricks. He is no longer just investigating his existing environment, but constructing a variety of spaces himself. In the next image the Lego house has been dismantled, but the play goes on. “Kateboard, kateboard,” the child calls out, and makes the Lego doll jump onto an imaginary skateboard. So, at the same time as the child has learned to build things, he has also learned to talk. The words he says are not subtitled in English, because it doesn’t matter if you don’t understand – the main point is simply to recognize that the child’s vocalization has become more multifaceted.

Originally my intention was to use more of the child’s speech in the work, and Virtamo and I made several recordings for it. But it soon became clear that the recordings would not fit into Two rooms and a kitchen, and we put together a separate nine-minute soundtrack out of them. Its title became Mitä patuttuu? A course in childspeak. The soundtrack has three parts, in all of which mother and child are looking at a picture book together. In the first part the child’s speech is still very simple, consisting mostly of monosyllabic words such as “hii” for “hiiri” (mouse) or “myy” for “myyrä” (mole). In the second part the child is already forming two or three-syllabled words, and in the third sequence whole sentences. Nevertheless, the syllables and letters still have a habit of swapping places. When the mother asks what’s happening (mitä tapahtuu) in the picture, the child turns the phrase into “Mitä patuttuu?” The errors are systematic, and in general the child’s speech sounds logical – just as if it came from some language related to Finnish. So, instead of my correcting the child’s errors, I give the viewer a course in childspeak. The work’s visual component has yet to be made, but the idea is to use moving letters in it in the manner of digital poetry. In style the work will, nevertheless, represent a primitive ‘language-tape aesthetic’.

REFLECTIONS IN A WINDOW PANE

In the last entry in my work diary I outline the abstract for the Nordic Summer University’s summer school, which was held at the Majvik Congress Hotel in Kirkkonummi, Finland, 24–31.7.2010. The Nordic Summer University, or NSU, is an institution founded in the 1950s, which comprises various study circles. Each study circle meets twice a year for a total of three years and, at the end, the group has a chance to make a publication, which the NSU then publishes. I myself belong to the study circle on artistic research: Artistic Research – Strategies for Embodiment. This began its work in February 2010, and so the Majvik summer school was our group’s second meeting.

20.4.2010

I am writing the abstract for the NSU’s summer school, yesterday’s grant application was actually practice for that. The subject of the artistic-research study circle is Laboratory. This makes it possible to present works-in-progress, and I intend to construct my abstract around Two rooms and a kitchen. But which aspect of the video would be a suitable topic for lab work? The description of the work seems to be going smoothly, and it may be that, at the end of July, there will be nothing left unfinished. Presenting the video would thus be more of an aid to the forthcoming writing work. What sort of subject or question would I want the other participants to shed light on? How could I use the summer-school laboratory to produce text?

One possibility would be to start off a conversation and tape it. But not everyone likes being recorded, that already became clear at the last seminar. And consciousness of the taping can block the free expression of ideas. Another possibility would be to show the work and then ask people to describe what they have seen, for example, for five minutes. To describe, not to interpret. To say what they saw and heard. If the material was usable, it could be the basis for making another video with no images at all, just the viewers’ verbal descriptions. It would be interesting to see how different that verbal description is compared with the original. Could this be one way of bringing out something about the relationship between image, word and sound?

The task I set for viewers could take the form: “What did I see? What did I hear?” The presentation could be spread over two days. On the first day, I could show the work and collect what people wrote down about it and, on the second day, I could present the ‘results’ of the experiment in some form. For example, I could arrange the texts into some logical order and ask two people to read them aloud, like a dialogue. That would be a kind of live version of the idea that I would make a videowork on the basis of the text later on.

Not a bad idea. I particularly like the idea of investigating one work by making another work about it. Thus, the idea of artistic research would also be implemented on the level of form: I research by making art.

The ‘laboratory experiment’ that I outline in the text was carried out according to plan and, the following winter, I repeated it once more in the Colloquium on Artistic Research in Performing Arts (CARPA) at the Theatre Academy Helsinki. In both places I began by showing Two rooms and a kitchen, and then asked the viewers to describe in writing what they saw and heard. The time for the writing was ten minutes. At Majvik I quickly edited a summary of the texts, which the actors Helka-Maria Kinnunen and Helena Kågemark read out on the following day. The CARPA conference was shorter, so I didn’t have a chance to work up the audience’s answers into a presentation, but I still wanted to give them an idea of what kinds of texts the others had written. So, I invited the members of the NSU study circle who were at CARPA to join me in reading out the texts produced at the summer school. For the performance I did a bit more editing on what had been written, and I further added to all this a text containing Elias’s comments on the video.

In the end, there were only three readers – apart from Kinnunen and me, the Norwegian choreographer Per Roar – but the experience was encouraging. To start the performance we opened the shutters that covered the auditorium windows, to let some natural light into the room. Then we each positioned ourselves beside our own window, and began taking turns at reciting the texts. I had divided up the spoken lines so that we each got to perform our own text (I read Elias’s words), otherwise the order was fairly random. Ideally, of course, each text would have been performed by a different person, but the whole thing seemed to work this way, too. From the situation I particularly remember the silence that reigned in the room, and the audience’s intent faces. After the performance, there was a discussion, during which I got a lot of positive feedback.

Even though I called the event a performance above, in the conference I used the word “reading”. In Finnish we might perhaps talk about a lukuharjoitus (reading rehearsal) or luenta (recitation). The name given is important, because the word “performance” easily elicits greater expectations than just reading. Above all, a performance takes our thoughts to the theatre or to performance art, even if my point of reference was more a conventional conference paper. That rather dry ‘genre’ has begun to interest me more and more, and I see a lot of possibilities for art in it.

IMAGES CREATED WITH WORDS

Already when I was writing the abstract for the NSU summer school, I had thought that I could, later on, use the text material as a basis for making a new videowork and, during CARPA, the image of the work became clearer in my mind. In fact, that image was so clear that it outright demanded to be made a reality. As I write this – in July 2011 – I am working on the script for the video’s soundtrack, and my aim is to get the work completed by the end of the year.

The image track for the new video is to consist of just a single shot: of the same almost fifteen-minute image of snowfall that recurs in Two rooms and a kitchen. On the soundtrack a bunch of people will describe what they are seeing or hearing in the reflecting surface formed by the window. The descriptions are to be based on the texts produced at the NSU and CARPA. But, unlike the conference performances, on the video each text is to be performed by a different person. They will also use the original languages of the texts – Finnish, Swedish and English. My plan is to do the taping at the NSU’s next summer school in Sweden in August 2011. Thus, at least some of the people who took part in producing the text will be able to read their own lines onto the tape.

The work’s title is going to be Heijastuksia ikkunaruudussa. In English, of course, this is Reflections in a window pane, which brings in the concept of “reflection”. In the research world this word is somewhat overused – I have begun to outright wince at it, since I feel I will never succeed in being sufficiently reflective. The new video can actually be seen as an attempt to re-appropriate the word. Instead of some nebulous “contemplation” or “meditation”, I view reflection literally in the sense of a mirrored image. On this occasion, it is not concrete room spaces that will be mirrored in the window, but images created with words.

SHOPPING LISTS AND PROSE

What, then, are the texts on the soundtrack like? In terms of their form they can be divided into two classes: shopping lists and prose. By shopping lists I mean texts that consist of single words or short, often incomplete sentences. Sometimes, the words have been sprinkled here and there, sometimes, they are divided into verses. Some of the shopping lists are almost like recipes: take a pinch of heavy white snowflakes and mix with everyday sounds…

Winter white

Black against the white

Time that passes

TIME

Sounds of the everyday

Warm wood against a naked foot

Heavy white flakes and black trees

Someone breathes in the whiteness[12]

The above text was written by the Swedish theatre director and researcher Cecilia Lagerström. Her colleague, the actor Fia Adler Sandblad’s, shopping list contains the same ingredients, but includes punctuation and whole sentences:

A window. White and grey. Bare.

It is snowing.

A baby is lying quietly. Breathing deeply. Sucking its thumb.

It is snowing.

A floor. A shiny, varnished wooden floor.

A bedroom with a Japanese wall and a cot.

Silence.

Sounds of bells and thudding.

The baby inspects its toy, a green egg-shaped doll that stands up when the baby pulls it down.

The baby is fascinated, completely engrossed.

Silence.

It is snowing.[13]

The prose texts have been written in longer sentences that are not divided into verses. The biggest contrast of all with the shopping lists and recipes is offered by the Slovakian Mladen Dolar, whose text might, for instance, be the opening of a psychological novel or an official’s report on a child. Dolar was not part of our study circle, but one of the summer school’s keynote speakers – an expert on Lacanian theoretical psychoanalysis and classical German Philosophy, as he was described on the NSU’s website. Slightly abbreviated, Dolar’s text goes as follows:

There is a flat, two rooms and a kitchen, as the title goes, and the flat exudes an air of security, prosperity and tastefulness. The homely appearance is displayed in contrast to the outside, sporadically shown through the window.

A child is growing up in these surroundings, and one can immediately see that this is a very good setting for the child to grow up in and discover the world. The child is maybe nine months old, imaginative, displaying great interest in and openness to the world around him. He doesn’t show any anguish, fear or discontent at any point.

Whether they are shopping lists or prose, all the texts seem to have their own structure. That is why I feel that these pieces of writing should not be over-edited, but that their natural rhythms should be respected. The texts, nevertheless, contain a lot of repetition, so shortening them feels justified. I already pruned the texts somewhat for the live performances, and I have to do this even more for the video’s soundtrack, so that the texts will fit into a fourteen-and-a-half-minute timeframe. It feels important that Reflections in a window pane is exactly the same length as Two rooms and a kitchen, so that the idea of the mirror image is enacted on this level, too.

CLING CLANG

In Dolar’s interpretation the space in Two rooms and a kitchen is clearly a good home – “a very good setting for the child to grow up in and discover the world.” That is why in the manuscript for the video I have juxtaposed the text with another one in which the issue appears in a different light. The author is the Norwegian dancer and researcher Sidsel Pape:

Clean apartment, no dust

not even when the workers were there

Clean child, not chaotic

Almost falling off a chair

Distressed mother, calm but frantic

Clean

Clear

Chaotic

Calm

Clean, calm, clear chaos

Clean, clear, calm chaos

It seems as if the writer does not really believe in the harmony of the home. She even thinks that the mother who appears at one point is somehow desperate. At the end, nevertheless, the psychologizing approach gives way, when the writer starts to play with words. At first sight, what immediately came to my mind was the tinkling toy that appears in the video: doesn’t “clean – calm” sound pretty much the same as “cling – clang”? Later, this association was combined with the observation made by another dancer, the Finn Annika Sillander: “I believe I heard music at the beginning of the film, but I am not sure.”[14] I don’t know whether Sillander was referring to the sound of the toy or something else, maybe the whirr of the washing machine. Nevertheless, it is intriguing to think that things can be present in the viewing experience that are not in fact on the soundtrack. Kaisu Koski, a Finnish video artist who lives in Amsterdam, even heard the sounds of snowfall and growth, along with the sticky soles of feet:

I heard the silence of the snowing. The border between the intimate home and the outside world far away.

I heard the child growing. The continuity of the domestic chores, with their never-ending cycles of heating, washing, drying, sewing…

I heard language evolving, freedom of intonation and melody.

I heard bare feet on a wooden floor, a little sticky. Although I didn’t actually hear them.

In the manuscript for my video Koski’s text is followed by the dramaturge Pauliina Hulkko’s assertion: “It is hard to separate what you see from what you hear, most of the pictures are associated with sound.”[15]

WHERE IS THAT NOISE COMING FROM?

One of the writers – the Portuguese sound researcher Eduardo Abrantes – responded to the question: “What did I hear?” by imitating the sounds on the video directly:

bzoon bzoooonnnn bzooon bzoonn bzooooon

frinfron frinfron frinfron frinfron frinnfron

muigeiiiigauagaua muigeiiiigauagaua

iaii aii iaii iaii

wooosh woossh wooosssh wooooosh

In the manuscript, Abrantes’s text is followed by the question: “Where is that noise coming from? Where is that noise coming come from, mother?” The person asking the question is, of course, Elias, whose comments I noted down. The text goes on like this:

It is snowing.

I eat paper.

I am wearing a green shirt, as a small child.

There are father’s shoes.

Where is my mother? There is my mother.

I want another one, mother. I want another film.

Look, the baby is sleeping in father and mother’s bed!

What is this room? It is not our kitchen.

What is that room?

Hey, why is that furniture covered?

A Christmas tree. I collected it with father.

Who made it?

Now, the baby is sleeping in my bed.

Mother, can you put another film on? Please.[16]

That text was saved on 19.8.2010, when Elias was just under four years old. The video was already almost finished at that point, and Elias saw when I was testing it on the television screen. He was generally used to watching children’s programmes on television, and, of course, compared to them, mum’s art video was boring – in the text, too, he asks me over and over again to: “put another film on.” Elias, nevertheless, watched to the end of the work and commented on it totally spontaneously. In terms of my future work the comments seem important, because you hear the protagonist’s own voice in them. What does a child experience when looking at his own picture on video? At least one thing that catches our attention is that, sometimes, he talks about himself in the first and, sometimes, the third person. I do the same myself when I use my own picture in works: sometimes, I am me, sometimes, a character.

OUTSIDE THE WINDOW IT IS SUMMER

Many of the texts written by viewers echo the structure of Two rooms and a kitchen: returning to the window at regular intervals. A good example of this is what the Finnish performance artist Pilvi Porkola wrote:

A window with snow falling outside

A view into a kitchen, water-green cupboards, white chairs

A baby sleeps, sucks its thumb, opens its eyes

And closes them again

The window with snow falling outside appears again

The baby is on its stomach on the floor,

Trying to reach a melodic rocking doll

The baby is on its stomach,

Playing with greaseproof paper, trying to eat it

The window with snow falling outside appears again

The baby gets up to stand leaning against the kitchen cabinet

The baby sits in a feeding chair, the baby sits under the table,

The baby eats an electric wire

Outside the window it is summer[17]

The original text is a little longer, but I wanted to end it with the word “summer”, since it is a surprising turn as the listener has already become accustomed to endless winter. Equally surprizing, of course, is when summer suddenly arrives in Two rooms and a kitchen. This happens at a point at which the complete plumbing replacement is going on in the apartment. The open bedroom window is covered in plaster dust, and behind it some green trees can be seen. It had not occurred to me that there was anything odd about this, since the majority of the apartment interiors had been shot in the summer – it just happened that no windows were visible in them. Added to that, to my mind, the winter shots occupied a different timeline from the interiors – snowfall represented the present, other images the past. Nevertheless, many viewers have found the green trees confusing. Further bafflement has been caused by the way that, after the plumbing renovation, nothing appears to have changed in the apartment. This made the Dane Ellen Friis – whose idea of the window as an hourglass I referred to earlier – interpret the renovation as a flashback. Friis’s complete text goes like this:

The window is like a clock

But it’s a clock which doesn’t show progress in time

It is an hour glass

Sleep is like the window

It’s a moment of rest before the next step

The interior of the apartment is a classical frame for development and growth

Flashback to the creation of the frame, when the apartment was redone and painted

This is the film’s meta-level

Viewers’ interpretations of the work’s temporal dimensions demonstrate that film time is by no means a simple matter. For example, no editing devices have been used in the renovation scene that differ from those in the rest of the video, and yet time ‘changed direction’ in Friis’s mind. As regards the winter window, I well understand that the viewer does not necessarily experience it in the same way as I do, who sees the landscape outside the window when sitting at my worktable. The snow falling on the other side of the window was, thus, the present moment at least in my working process when I edited the video in the late winter of 2010. To the outside viewer the idea of two time levels is perhaps too complicated a construct, or it should have been brought out more clearly.

The audience’s confusion during the renovation sequence had me pondering the true nature of the plumbing replacement, ‘philosophizing’ at its expense, inspired by Bachelard. Compared with conventional repair or painting work, a complete piping replacement is like a massive surgical operation. It is not applied to the building’s surface, but to its structures, its ‘interior organs’. The skin of the kitchen and bathroom are opened up and the corroded pipes exposed. After the operation, the wound is sewn up, and no change is necessarily visible from the outside. For the person living in the apartment the experience can, nevertheless, be a gruelling, even a traumatic one. It is shocking to see your home like a bomb has hit it. This made me think of the history and future of this building built in the 1920s. The renovation thus opened up a new viewpoint on the space, and that is why it seemed important to include it in the video, too.

SCALE

Even if the viewers’ texts have a lot in common with each other, their scale or perspective varies. Where in Pilvi Porkola’s text we are sitting with the child under the table, the writer of the following text – whose name I do not know – seems to observe things from somewhere far away, from another country, and even from another century:

What did I see?

An ideal home, very clean

A privileged human nest in Finland in the early 21st century

IKEA is everywhere

The global viewpoint is accentuated by the assertion “IKEA is everywhere”. Like Sidsel Pape, the writer also notes the tidiness of the apartment. This is something that recurs in many of the other writings, too, and it clearly evoked conflicting feelings. It made the Belgian architect Thierry Lagrange doubt the veracity of the video, and even his own senses:

I saw clean rooms and a kitchen. The floor reflected the furniture. There was no dust. Was it real?

I heard what I saw. Did I hear right? I heard my own kids touching, finding, being confronted with what they see and hear.

The snow brought in silence. Was it real? There was no dust in the sound.

In all honesty, I have to say that our home is not quite as tidy as the video would have people believe. When filming, I have a habit of ‘styling’ the reality in front of the camera, of arranging it according to the classical rules of composition. Another reason for the impression of cleanliness is that dust, finger marks and other signs of life simply do not show up in a relatively low-resolution video image – especially in an extreme long shot. And most of the images in Two rooms and a kitchen are such broad, tableau-like views. The framing of the shot, for its part, emphasizes the theme of space. The child is seen from a distance, as part of the room space, sometimes even behind a piece of furniture. He frequently also has his back to the camera, which seems to make him abstract, less of an individual and more of an image of a human being.

“YA YA YA YA YA”

In addition to the home and the child, the window pane also reflects the viewer’s own image. This is seen, for instance, in the way that the art disciplines represented by the writers affect their interpretations. For example, the British performance artist Louise Ritchie sees the child’s activities as a kind of dance:

I saw a beautifully uncoordinated choreography of waving, lifting toes, opening the mouth, kicking, rocking. I saw an attempt to consume objects, uncertain of their purpose.

I heard sounds of domesticity, sounds of play. Unexpected sounds, sparked by curiosity and unusual relationships between mouth and paper – wire and leg.

I heard the landscape of domesticity through the body of the child.

Per Roar’s text also accentuates physicality. “I do not hear, but sense,” Roar says, and particularly picks out of the child’s movements, especially their rhythm:

I hear water pumped into a washing machine.

I see silence outside the window.

I do not hear, but sense.

White, white, white

A ball of orange and green

A twinkling sound

I see an infant exploring the interior of a home

I hear a squeaking door, I see a swinging door, I feel the joy of rhythm:

Sound – action, action – sound

Slow – quicker, quicker – slower

“ya ya ya ya ya”

The outside whiteness never ends

No, a glimpse of green in the window

Blackout

The machine ends its cycle

The work is done

I can open the door

Roar’s text is the last in the video’s manuscript. Reflections in a window pane thus ends at the same point as Two rooms and a kitchen: with the end of the washing-cycle. The phrase “I can open the door” can be interpreted as referring to the door of the washing machine, or then it can be seen more broadly as permission to exit the world of the work.

THE SMELL OF A SALMON BAGEL AND PEACH WATER

Among my papers there is yet one more text that I wrote myself while the others were doing the writing assignment at Majvik. I do not intend to use the text in the new video, but it might be interesting here, since it is like a page of the work diary:

27.7.2010

Image too bright. Should have checked before the presentation. Sound set too high, fortunately it was possible to correct it during the screening.

People laughed. Somewhere on the back row. I didn’t dare to turn my head and look. Just now, I glanced at who was sitting there: Cecilia, Sidsel…

The laughter came at the point when the child was climbing onto the table, when he was eating the power cord and trying to open the kitchen drawers that were jammed with a wooden stick.

At the end, silence, of course.

Mladen is also writing. What will come out of that? Fascinating to see.

At first, it annoyed me when people arrived late, even though I had particularly asked them to come on time. My annoyance shows, I am aware of that.

So what? Surely you can get annoyed when you yourself prepare carefully and this lot don’t care…

Soon, ten minutes has passed. I end the task. I further ask the participants to put their names on the paper.

The feelings of curiosity, excitement and annoyance that I express in the text prompt the question of how the others experienced the situation. Did they, too, get annoyed, even if perhaps for a different reason from me?

On the basis of the feedback I received, it seems that, at least in Majvik, the ‘experiment’ elicited mostly positive feelings. Someone even came to thank me for the experience that the writing assignment gave them. Another, meanwhile, observed how rarely we tell each other what we are seeing or hearing – in giving feedback, we often switch directly to interpretation and criticism. Despite their slight lateness, people were also amazingly ready to take part in the experiment. This perhaps stemmed from the fact that the majority of the audience came from the performing-arts side, where all manner of play is the norm. As a visual artist it has actually been liberating for me to get to know this art-making culture that is more collective than my own.

Only one writer has been outright critical of both the videowork and the giving of the assignment. This did not happen in the conferences I mentioned before, but at the University of Helsinki, where I was telling people about my working process in March 2011, invited by the researcher Kimmo Sarje. This was a course presenting artistic research, and instead of simply giving a lecture I wanted to demonstrate my working process in practice. At the same time, I was, of course, curious to see what kinds of texts the university students would produce.

At the University the writing time was only five minutes, but otherwise the arrangement was the same as at the NSU and CARPA. The critical student – of whom I only know the first name – reacted to it like this:

What do I see? I see an ordered everyday composition, in which things do not begin or end, but appear as definite events. The objects are made of plastic, a child is playing. The winter landscape into which it fades does not change, it is from the same clip. Likewise, the home is static.

What do I hear? A potpourri of everyday sounds: there is a microwave, the clatter of dishes, the child’s bawling, singing… it is all very clinical.

I also heard the space in which I am now: the technology, the air conditioning, the people…

What do I smell? My salmon bagel, peach water and my too-rapidly aired woollen pullover. I resist being managed! And the 5 min ended ages ago.

Rgds. Katri[18]

The most interesting thing about the text, to my mind, is the way the writer brings the presentation situation, and even the accompanying olfactory sensations, into the text. The smell of the salmon bagel, peach water and woollen pullover remind us of the hierarchy of the senses: Why were my questions linked specifically to seeing and hearing? What idiosyncratic answers would I have got if it had occurred to me to ask what odours viewers smelled in the work? Or what taste sensations does the video induce? In practice, the way I asked the questions was, of course, influenced by my research topic – the interaction of image, word and sound – but that, too, can be called into question.

The texts by the other university students did not differ in any way worth mentioning from the responses I had got earlier, and in the end I decided to limit the material in Reflections in a window pane to the texts produced at NSU and CARPA. This framing is, of course, open to criticism: wouldn’t the video be more multi-faceted if I were to give the assignment to more people representing different professions, social classes or genders? On the other hand, I am intrigued by the idea that a work that had its beginnings in the artistic-research study circle, is also being carried out as a collaboration between artist-researchers.

FINALLY

To end, I would like to return once again to autoethnographic research and, in particular, to Karen Scott-Hoy’s article that I mentioned in the first half of my essay. The title of the text is “Form Carries Experience: A Story of the Art and Form of Knowledge”, and it describes the genesis of a painting. The painting’s starting points are the writer’s experiences on the island state of Vanuatu in the Pacific Ocean. And yet this is not artistic research, but a kind of artistic ethnography (artistic evocative ethnography), which utilizes emotions and mental impressions.[19] Alongside doing research, Scott-Hoy worked in an eye clinic on Vanuatu.

The article began to interest me, not just because of its subject matter, but also because Johanna Uotinen criticized it very strongly in her own text: “Kokemuksia autoetnografiasta” [Experiences of autoethnography]. Even though Uotinen thinks Scott-Hoy’s subject – the process of creating an artwork – is a good one, she finds the writer’s approach difficult. “The text is… such a stream of consciousness that, with the best will in the world, I am unable to see what it is trying to say.” Uotinen writes.[20]

Having perused Scott-Hoy’s article, I, in turn, cannot, “with the best will in the world”, understand what is so difficult about it. Right at the start, the writer makes it clear that her aim is to give an expression to her experiences that is more comprehensive than is generally achieved with academic writing. The text is not stream-of-consciousness, but rather it is a carefully constructed whole. Even the research question is articulated clearly: “What is the experience of cross-cultural health-work like?”[21]

The only problem that I have with Scott-Hoy is with the painting itself. Based on what the text says, the painting seems quite complicated, and the accompanying sketch reinforces that impression. When, on top of that, nearly everything symbolizes something, the whole thing begins to feel a little naïve. That feeling is exacerbated by the fact that the painting process appears to lack any real struggle. By that I mean the endless refining of details, the wiping off and redoing, that at least take a lot of my time. It may be that the easiness of the painting process is only an illusion that arises from the narrative created after the fact, but as an artist I am left wanting a more trenchant attention to the form of the work.

What is admirable, in contrast, is the multi-faceted way in which Scott-Hoy uses various literary devices. She starts off by leading the reader into a bedroom, where beside the bed there is a sketch pad. The narrator describes how she reaches beneath the covers, takes hold of the pad, and begins to draw. At the same time, she recounts her frustration with the academic world and her own role as a researcher. The text soon turns into a dialogue between the writer and her husband. Just when the reader has been lured into forgetting the intimate setting for the conversation, the man bends down and kisses the woman. When the man has got up from the bed, the woman again picks up her pad, and carries on drawing. In the next section the sketch is lying on a bench in the workroom. The woman looks at it and starts painting a self-portrait based on it. The progress of the painting is described step by step, just as if its maker had noted down each brushstroke in memory. Occasionally, the painter takes a step back and looks at the picture from further away. In this same way she ‘takes a look’ at her experiences on the islands of Vanuatu up to that point. At one stage, the artist glues a short story that she has written earlier onto the canvas, and this is also included in the article. As a whole, Scott-Hoy’s text could be a prototype for how research comes close to literary expression.

In the dialogue heard in the article some of the spoken lines have been borrowed directly from ethnographic research literature. This gives the conversation a papery taste, but, on the other hand, it is a nifty way of contextualizing the work. In fact, I am a bit envious of this invention, since the contextualisation of my work has caused me a lot of headaches. My previous article – which was based on taped conversations between myself and sound designer Virtamo – was criticized specifically because the text did not contain any references to other artists or writers. When commencing this essay, I tried to remedy this omission by reading all sorts of stuff related to the subject matter of my work, but the majority of the references got left out in the writing process, since their relationship to my works felt contrived. This prompted me to ask: What is the role of research literature in artistic research in general? There are works that require background knowledge for their execution and, in that case, literature naturally becomes a part of the text. In my own production this is represented, for example, by the Tango Lesson (2007) video, for which I had to read scientific articles about the sound world of the foetus. But as a process Two rooms and a kitchen was quite different – its ‘sources’ were sensory experiences, observations, everyday life. How am I to present them as a context that can be taken seriously?

Keeping a work diary was one attempt to describe the kinds of ingredients that go into the genesis of my works. At the same time, it was an attempt to try out quick, spontaneous writing, which was, admittedly, combined with conventional essay writing later on. Now, as I am finishing this essay, I notice that it is a direct continuation of the preceding articles in my thesis. Everything seems to be connected by a certain rebellion against academic models, a need to seek (as ethnographers do) alternative ways of writing. My first article, “Tango Lesson – Study on the encounter of empirical science and art” (2009) still looks like a traditional essay, but a bit of parody sneaked in there. My second text “What does silence sound like?” (2011) took the form of a dialogue, and the next thing I tried was a diary. Another form of writing was the collective text that came about at the NSU summer school and at the CARPA conference and, on the basis of which, I am now constructing a new videowork. In this experiment I am particularly fascinated by the polyphonic nature of the text: the work does not consist solely of my talking, but of the voices of several other people representing different art genres and nationalities.

In addition to rebellion, my writing is motivated by an attempt to achieve aesthetic pleasure. Often, this leads to a simplified expression: even if the idea could still be taken further, the rhythm of the text demands that I put in a full stop. In terms of logical argument this may be a weakness, but I quite simply cannot go against myself. A light, airy phrase brings me the same kind of satisfaction as a picture with a beautiful light. In this essay many of the subheadings are also like pictures (or sounds), and even the structure of the essay follows the logic of a two-part artwork. What is perhaps special is that the second part of the ‘diptych’ was written before the videowork that is its subject was completed. On the other hand, this is a reminder that every text has been made at a certain time and place, at a certain point in the progress of the research. Thus, every article is like an entry in a work diary: this is where I am today, July 8, 2011 at 16:03.

References

Bachelard, Gaston 1994: The Poetics of Space. Translated from French into English by Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press. (Original French La poétique de l’espace published in 1957.)

Bachelard, Gaston 2003: Tilan poetiikka. Translated from French into Finnish by Tarja Roinila. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Nemo. (Original French La poétique de l’espace published in 1957.)

Friedberg, Anne 2006: The Virtual Window. From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nelson, Gunvor 2002: Still Moving. I ljud och bild. Karlstad: Karlstad University.

Salo, Ulla-Maija 2007: “Etnografinen kirjoittaminen” in Sirpa Lappalainen, Pirkko Hynninen, Tarja Kankkunen, Elina Lahelma and Tarja Tolonen (ed.) Etnografia metodologiana. Lähtökohtana koulutuksen tutkimus. Tampere: Vastapaino, 227–246.

Scott-Hoy, Karen 2003: “Form Carries Experience: A Story of the Art and Form of Knowledge”. Qualitative Inquiry 9:2, 268–280.

Uotinen, Johanna 2010: “Kokemuksia autoetnografiasta” in Jyrki Pöysä, Helmi Järviluoma and Sinikka Vakimo (ed.) Vaeltavat metodit. Joensuu: Suomen Kansantietouden Tutkijain Seura, 178–189.

Wollen, Peter 2002: Paris Hollywood. Writings on Film. London and New York, NY: Verso.

Notes

[1] Professor in Media Studies Eija Timonen, University of Lapland.

[2] Professor Jan Kaila, Finnish Academy of Fine Arts.

[3] Uotinen 2010, 179.

[4] Uotinen 2010, 186.

[5] Uotinen 2010, 181.

[6] Salo 2007, 236–238.

[7] Nelson 2002, 36. The quotation is from an interview with Nelson, in which she is asked what she prefers to call her works – experimental film, avant-garde, underground or something else?

[8] Wollen 2002, 240.

[9] Friedberg 2006, 1.

[10] Bachelard 1994, 4.

[11] Bachelard 1994, 14–15.

[12] Vintervitt/ Svart mot det vita/ Tiden som passerar/ TID/ Vardagens ljud/ Varmt trä mot naken fot/ Tunga vita flingor och svarta träd/ Någon snusar i det vita.

[13] Ett fönster. Vitt och grått. Kalt. Det snöar. En bäbis ligger lugnt. Andas tungt. Suger på sin tumme. Det snöar. Ett golv. Blankt lackat trägolv. Ett sovrum med japansk vägg och babysäng. Tystnad. Ljud av klockor och dunsar. Bäbisen undersöker sin leksak, en grön äggformad docka som reser sig upp när bäbisen drar ner den. Bäbisen är intresserad, helt upptagen. Tystnad. Det snöar.

[14] Jag tror jag hörde musik i början av filmen, men är inte säker.

[15] On vaikea eritellä nähtyä kuullusta, useimmat kuvat liittyvät ääneen.

[16] Sataa lunta. Minä syön paperia. Minulla on vihreä paita pienenä lapsena. Siinä isän kengät. Missä minun äiti on? Siinä on minun äiti. Haluan toisen, äiti. Haluan toisen elokuvan. Katso, vauva nukkuu isän ja äidin sängyssä! Mikä tämä huone on? Ei se ole meidän keittiö. Mikä tuo huone on? Hei, miksi nuo huonekalut on peitetty? Joulukuusi. Minä keräsin sen isän kanssa. Kuka on tehnyt sen? Nyt vauva nukkuu minun sängyssä. Äiti, voitko laittaa toisen elokuvan? Ole kiltti.

[17] Ikkuna jonka takana sataa lunta/ Näkymä keittiöön, vedenvihreät kaapit, valkoisia tuoleja/ Vauva nukkuu, imee peukaloaan, availee silmiään ja sulkee ne jälleen/ Ikkuna jonka takana sataa lunta toistuu/ Vauva on vatsallaan lattialla ja yrittää tavoittaa melodista kiikkuvaa nukkea/ Vauva on vatsallaan ja leikkii voipaperilla, yrittää syödä sitä/ Ikkuna jonka takana sataa lunta toistuu/ Vauva nousee seisomaan keittiön kaapistoa vasten/ Vauva istuu syöttötuolissa, vauva istuu pöydän alla, vauva syö sähköjohtoa/ Ikkunan takana on kesä.

[18] Mitä näin? Näin hallinnoitua arjen sommitelmaa, jossa asiat eivät ala tai lopu vaan esittäytyvät määriteltyinä tapahtumina. Tavarat ovat muovisia, lapsi leikkii. Talvimaisema, johon feidataan, ei muutu, on samasta klipistä. Samoin koti on pysähtynyt. Mitä kuulin? Arjen äänien potpurrin: on mikroa, astioiden kolinaa, lapsen ölinää, laulua... Kaikki hyvin kliinistä käsittelyn myötä. Kuulin myös tilan, jossa olen nyt: tekniikan, ilmastoinnin, ihmiset... Mitä haistoin? Lohibaagelini, persikkaveden ja turhan nopeasti tuuletetun villapaitani. Käyn hallinnointia vastaan! 5 min myös loppui jo aikoja sitten. T. Katri

[19] Scott-Hoy 2003, 268.

[20] Uotinen 2010, 181.

[21] Scott-Hoy 2003, 268.

Translation: Michael Garner