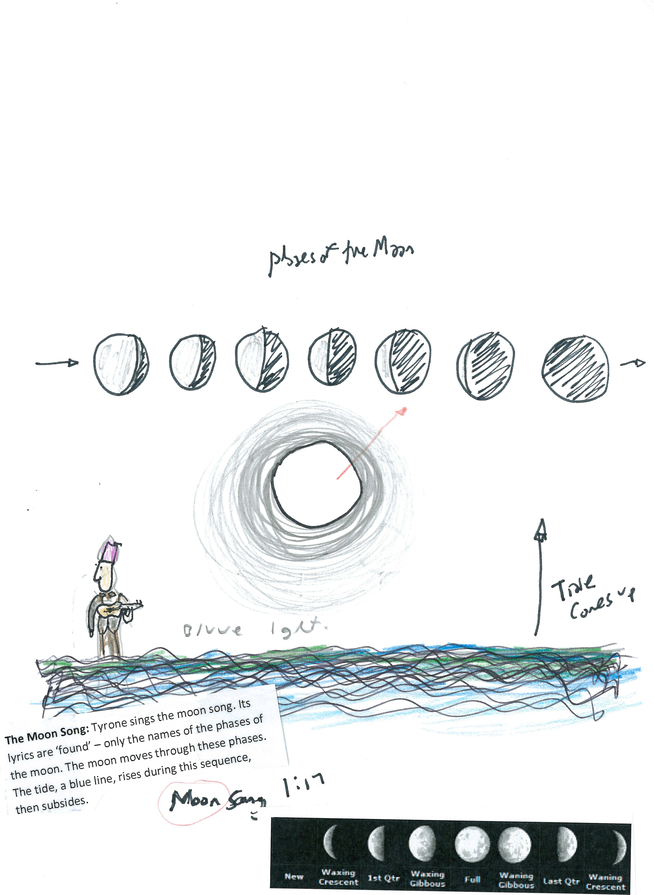

Tyrone (David Megarrity) & images from notebook illustrating initial ideas and images sourced from original song lyrics

Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot: illuminating creative emergence in Composed Theatre

1.1 Introduction to the Creative Work

Amongst the most beautiful of the ‘strange objects’ (Pavis 2013: 61) of contemporary performance are creations of Composed Theatre (Rebstock & Roesner 2012). Always intermedial, often idiosyncratic, and born of the materials and circumstances of their production, they’re built to surprise. This creative field can however, be enigmatic in discourse and inscrutable in display. It’s certainly resistant to easy explication. In a way, the performance maker choosing to work in this realm faces the prospect of having to start again every time. Composed Theatre has been recognized as a new grouping, even a new form, but a cutting edge is of no use until you can get a handle on it.

We wanted to collaborate on a new work of Composed Theatre. That was the aesthetic impulse. With respect to the rich historical stream of collaborative and devised theatre-making, we wanted to balance experimentation in process with accessibility in product. The key driver of this research was critical engagement with a highly musicalized creative development process in which the shape of the project would be emergent, rather than predetermined. This project began with original songs, and we wanted to extend the sense of discovery and surprise which characterised their musical composition into the process of devising an intermedial performance around them.

Time and again, songwriters evoke the idea of emergence in their work. Paul Simon says that he doesn’t:

consciously think about what a song should say. In fact, I consciously try not to think about what a song should say…Because I’m interested in what…I find, as opposed to…what I’m planting. I like to be the audience, too. I like to discover what’s interesting to me, I like to discover it rather than plot it out. ...Because three consecutive thoughts imply direction. They don’t necessarily imply meaning. But they imply direction. And I think direction is sufficient. When you have a strong sense of direction, meaning clings to it in some way.

People bring meaning to it, which is more interesting to me than for me to tell meaning to somebody. I’d rather offer options to people. Options that have very pleasing sounds. (in Zollo 2003: 95)

In a way, Simon is suggesting here that he’s looking for something to stumble across – those rich moments where the artwork appears to be telling the artist what to do, rather than the other way around, and that this process (so familiar to composers) of allowing the artwork to emerge has potential dividends for the audience as well. Bedeau and Humphreys point out that the ‘topic of emergence is fascinating and controversial in part because emergence seems to be widespread and yet the very idea of emergence seems opaque, and perhaps even incoherent’ (2008: 1). Working in the mode of Composed Theatre, we sought to transfer the emergent quality of song writing to the collaborative devising of a performance which frames those very songs. Jaegwon Kim describes the core ideas of emergentism:

As systems acquire increasingly higher degrees of organizational complexity they begin to exhibit novel properties that in some sense transcend the properties of their constituent parts, and behave in ways that cannot be predicted on the basis of the laws governing simpler systems (in Bedeau & Humphreys 2008: 127)

This project began with the hope that these emergent would appear. This article traces processual dialogue between artists and art forms in the creative development of a new work which explored if and how a whole show could be like a song. While the aesthetic resources of screen and music united in performance provided a clear intermedial starting point, the developmental trajectory and specific outcomes were unknown at the outset.

Entering the development through form, rather than content, this project of practice-as-research isolates and analyses the coevolution of live musical performance and projected moving images as the art forms converge and co-adapt each other. We also wanted to capture key features of this particular process order to better address intermedial challenges inherent to Composed Theatre.

2. Elements and Construction of the Work

Before the intermedial characteristics of Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot are discussed, the properties of each component medium will be identified. This project combined screen, song and performance, yet each of these three elements had a fairly distinct set of characteristics that should be described before examining how they interacted and transformed one another.

2.1 Performance Personae

Philip Auslander asserts that ‘what musicians perform first and foremost is not music, but their own identities as musicians. Their musical personae’ (2006: 102). This concept of the performance persona was vital to this research. The singer and the song united in performance on a stage, whether it be in a musical, or theatrical frame, can be a remarkable phenomenon. This is an approach to performance that seems very personal and unique to the singer: David Byrne captures its inherent paradox, observing that:

…one can sense that the person on stage is having a good time even if they’re singing a song about breaking up or being in a bad way. For an actor this would be anathema, it would destroy the illusion, but with singing one can have it both ways. As a singer, you can be transparent and reveal yourself on stage, in that moment, and at the same time be the person whose story is being told in the song. Not too many other kinds of performances allow that. (2012: 73)

‘Tyrone and Lesley’, as a pair of personae, had been developed organically over many years, in both theatrical and musical contexts, as a way of blending differing training and skills. They essentially became a performance vehicle for the songwriting collaboration that Samuel Vincent and I had created, and the tacit dialogue between performers, personae and production added to the style texture and content of Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot.

In the show, Tyrone and Lesley have self-consciously employed intermedial elements to enhance their presentation and expand their appeal, as Tyrone helpfully explains:

TYRONE: You seem like people of refined pleasures. Allow me to applaud your good taste in ukulele players this evening. We’re in a bit of a spot, you see, because we’re not quite as famous as we should be. So we’re looking forward to playing for you tonight, as well as enhancing our performance with the addition of this…

(he indicates the screen)

…thing. Quite a lot of expenses have been spared in bringing you this presentation, which we really think might push us into cult status. Just you wait. (Megarrity & Sibthorpe 2016: 4)

There is no veil obscuring (yet also no unveiling of) the shared identities of writer, musical performer and personae in this performance. In self-consciously negotiating the relationship between words and music, organizing and presenting the material as a performance, rather than focussing exclusively on music, or imposing a mantle of theatrical fiction (and concomitant strictures of ‘character’) the intent was to actively play with the tension between the program of the presentation and the performance personae putting it over. In this way, the ‘listeners are always aware of the tension between an implied story (content: the singer in the song) and the real one (form: the singer on the stage)’ (Frith 1996: 209).

1.2 Practice-as-Research

Baz Kershaw’s playful question “What are methods for, but to ruin our experiments? (Kershaw & Nicholson 2011: 65) points not only to the essential play of the unknown in creative practice, but also a perceived antipathy between the “aesthetic and the epistemic” (Gingrich-Philbrook in Spry 2011: 105), and it is true that each feels different. Working in the qualitative field of performance as research, the research methods of this project are Practice-Led. They draw from Nelson’s triangular model of Performance as Research a dynamic methodological triangle in which practitioner knowledge, critical reflection and conceptual framework operate in relationships of conjunction and mutual influence where “the product [the performance] sits at the centre of the triangle” (2006: 113).

An intermedial project necessitates multimodal means of data collection. As such, creative processes were documented through journaling, correspondence, drawings, video product, videography, photography and audio recordings of performance, and draft scripts, dated and gathered in a shared online repository. This data proved instrumental in isolating the general principles that follow, especially in a practice-led project in which the artist is also the researcher. Interaction with artistic collaborators, captured in written and recorded exchanges, was also a key to understanding the intermedial relationships in the artwork. Collaboration is not incidental to this activity, and is defined as:

a process of shared creation: two or more individuals with complementary skills interacting to create a shared understanding that none had previously possessed or could come to on their own […]. Real innovation comes from this social matrix. (Schrage 1995: 40)

Keith Sawyer (2003) points out that ‘because group creativity is emergent, the direction the group will travel is difficult to predict in advance.’ This mode of collaborative creation, often referred to as devising, will be familiar to most theatre practitioners. It problematizes the text or script as a starting point for a work, and, as Harvie and Lavender point out, it:

entails openness but within programmatic parameters. In resonance with certain aspects of digital culture, it depends upon networks of connections made between participants that can be variously made and remade: it is therefore differently generative than much theatre that has gone before – it inherently enables plural, simultaneous strands of development and the more evidently organic growth of the whole. (2010: 14)

This summarizes our approach to this creative project and means that while we had a broad sense of what the show might be like, we wanted to leave the development of the show wide open to surprise, allowing form to lead, rather than content. While this piece could combine theatre music and screen, we didn’t want the work to be demonstrating any thesis based in content, subservient to predictable narrative structures, nor be willfully abstruse. We wanted the show to be engaging and funny for our audience as they witnessed us striking this balance.

2.4 Going for a song: the role of the setlist

The building of the show began with a mass of nearly 50 songs, which were audited, shortlisted, and setlisted into a group 27 which served as the matrix of this creative development. The order and progression remained undecided. An important element of the curation process was a realisation that many of the compositions shared similar images or metaphorical flavours. Features of the natural world such as seas, skies, clouds and moons often appeared, in addition to elements of domestic interiors such as windows, light bulbs, and a half-full glass. This audit of existing material revealed a subset of lyrics exploring a kind of optimism, most probably as a result of the musical influence of Al Bowlly, Ray Noble and similar British dance band artists and composers from between the wars.

The setlist was initially a list of songs, but before long grew into a representation of sequences which contained potential video projection, physical action and text alongside their musical content. This enhanced setlist often contained quick drawings and sketches.

Developed through sketches on paper and screen, these images we derived from the songs coalesced into a set of symbols intended to integrate with the music in performance as projected images. The ‘spot’ (nominally a plain white circle meant to represent a theatrical spotlight) for example, developed the ability to transform into other circular objects such as a moon or ukulele’s sound hole as well as becoming animated and eventually performing as the light source it was initially intended to only represent. Thus lyrics were transformed into images as the development process shifted into video design and prototyping. As each song became a potential component of the show, it gathered layers of music, image, action and text, coalescing into intermedial fragments – some simple, some more complex. The setlist was whittled down to eighteen.

The very limited time, space, financial and technical resources around the creative practice cannot be discounted as a critical factor in the development of the work, and therefore the research it embodies. Unsurrounded by the support of designers, directors, stage or production managers, dramaturgs (or wages) the team of three worked very closely in modes which encompassed a multiplicity of roles on page and stage. The provisionality which emerged was a key characteristic of this creative process. The ‘not-knowing-what’s-coming-next-ness’ that we mindfully engaged with in developing the show was permeated with a ‘we-can’t-afford-to do-that-ness’ which led to a ‘for-the-time-being-ness’ and in many cases a ‘this’ll-have-to-do-ness’.

Necessity forced invention in both phases of this project. This invention resulted in aesthetic discoveries embedded in the performance, as well as selected features of our process which are here distilled into a few general principles for intermedial work in Composed Theatre.

3.2 Dislocating writing: plasticity of form and structure

Playwriting is the describing of action that does not yet exist, as if it does. This particular mode of writing had a role to play in the creative development, but it was not at all the sole generator of material. Words are easier to compose when a moment has been prototyped in performance. Therefore in this way, rather than the writing instigating the artwork, the artwork instigates the writing.

The act of ‘writing’ was also dispersed over a range of activities, both within the creative process and beyond, with paratext such as grant applications, marketing blurbs and production briefings framing the way others may perceive the work. In this way the writing around the work can almost be as significant as the writing within it.

Sometimes writing involved the aforementioned setlist, a common enough locus for the work of structuring musical performance. Placing each song on its own slip of paper not only enabled the order to be reconfigured but also more than one person to physically restructure the selection.

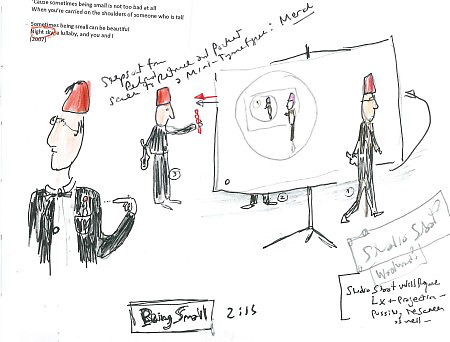

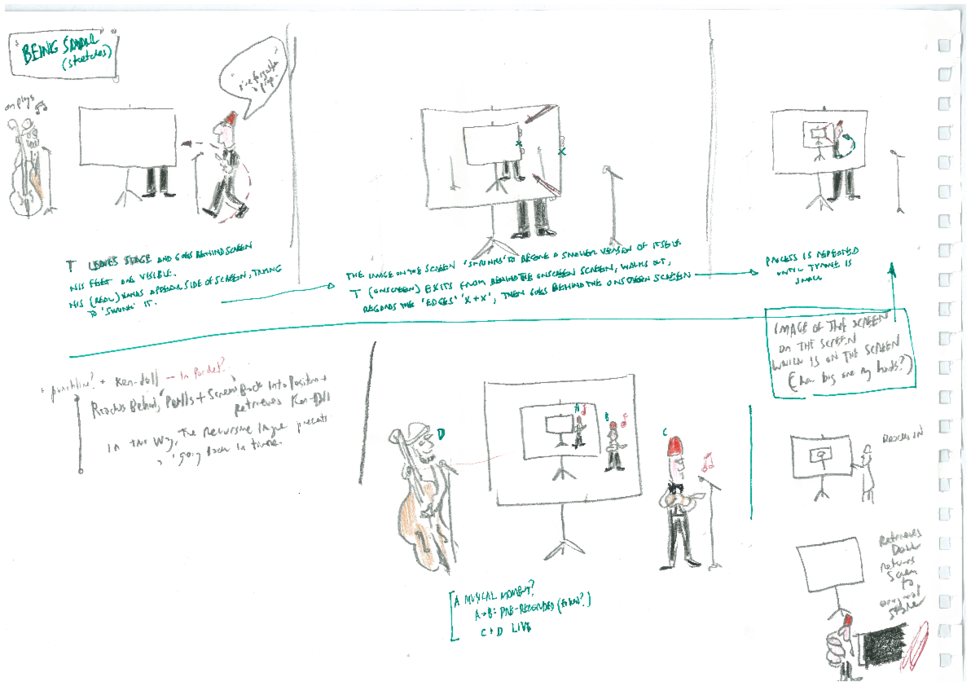

Sometimes the writing involved drawing. It can be better draw a series of stage images than write them, especially once those images become recursive. In this project for example, the images of screen on screen involved in the mise en abyme sequence were more easily drawn than described.

Sometimes the writing involved making video. Certain obscure corners of the development were brightened by making a rough little film. Sometimes this was about testing sequences and rhythms, sometimes it was about testing technical or stylistic possibilities. Sometimes the video-making was about mixing contemporary and vintage technology in sequences such as the sing-along bouncing ball sequence which concluded the show.

Performance and rehearsal can, at a stretch, also be considered acts of writing. It’s fine to write a list of songs in sequence, but to stand up and play that setlist in real time is something else altogether. Certain simple sequences of projection, action and music played as outlined in the script, while other more complex propositions only made sense in their ‘full performative interactions’ (Sibthorpe, personal communication), which were then reinterpreted and fixed in readable form in the script.

The songs seem fixed but are flexible: the writing across all these locations shifts and grows in response to music, video is quickly constructed and tested in performance, which again loops back in on the writing as new possibilities emerge and the visual, musical and textual language of the piece develops.

At many times during the process this same plasticity offered an immediate sense of us performing a kind of intermedial ‘jamming’: collaborative creation in a seriously playful improvised mode. Once we’d developed certain parameters, and worked the materials into a sufficiently useable state, it allowed us to play with possible, rather than probable outcomes. Keith Sawyer points out that:

“because group creativity is emergent, the direction the group will travel is difficult to predict in advance.” This implies that a “creative group is a complex dynamical system, with a high degree of sensitivity to initial conditions and rapidly expanding combinatorial possibilities from moment to moment” (2003: 12).

For example, the ‘spot’ of light was not locked off in draft form, and was therefore able to move and respond to the performers. This was principally because of the way Nathan had set it up in the cue-based multimedia software, as well as his openness to change:

The flexibility we achieved in the process – being able to modify visual sequences on the fly or assemble new sequences efficiently was about using QLAB in a certain way that is sympathetic to the development mindset. Where I might normally render sequences to be a single flat file, in this workflow I am exporting separate layers so that they can be endlessly tweaked in QLAB. It’s like doing part of the video editing live in QLAB’s interface – a simplicity of infrastructure and commitment to proof of concept rather than finished product standards of output. (Sibthorpe, personal communication)

This meant that a roughly rendered video of a circle of light, in addition to its metaphorical potential had a practical function as a light source, and effectively became a prosthesis allowing the video artist to ‘play’ alongside the musical performers in real time.

The musical and performative aspects of the show were handled in a similar fashion. If suddenly a song we’d planned to use wasn’t sitting right with the screen and action, we substituted another. If it gets a laugh, or creates an intriguing effect, we use it. We don’t dwell on how or why it works, because to do so in this playful mode this would stop it working.

The structure of the performance responded to this plasticity and emerged as a process of orchestrating reveals of each of the intermedial layers of came to comprise the show. Because these layers were visual and musical, with language of any kind an unreliable force, the emerging work was both setting up and breaking its own rhythms and conventions, purposefully playing with expectation, just like only music can. Nathan referred to this as ‘the promise of change and unexpected shifts’.

The plasticity of each art form contributed profoundly to the intermedial relationships of this piece. Surely if we’re seeking to surprise our audiences we must set up intermedial development processes so they can surprise us as artists. Highlights of both creative process and performance certainly proved the success of this dynamic. The mise en abyme sequence at the heart of the show was carefully written and thoroughly constructed, but it was not until ‘Tinyrone’ (a Ken Doll dressed as Tyrone) unexpectedly appeared above the screen, illuminated by the wandering white spotlight, that the segment took flight. This was unanticipated by script or design. Neither element was completely ‘novel’ in terms of our established conventions, yet the extremely playful manipulation of scale, screen, space and song made both artists, audiences think ‘that’s not supposed to happen’. Laughter (of the team, as well as test audiences) formed an important part of these mutations as our plans change for the better and the art forms mutually influence one another.

As the development period closed, the setlist was no longer solely songs, but rather comprised of intermedial sequences which were shifted into an overarching structure based in orchestrating reveals of increasing complexity. A parallel setlist was created by musician Samuel Vincent, as he calculated keys, motifs and segues for the live double bass soundtrack he provided to sew the pieces together. When pre-recorded music was employed in the final stages of development, both musicians played live additions over it.

The script work continued as a gathering point for all of the formerly ‘dislocated’ writing, because the show must be run from a master document which will also enable future remounts. This text-based work breaks the performance up into three acts, echoing David Mamet’s masterful line between evolution, musical structures and the three-act structure of drama:

Our survival instinct orders the world into cause – effect – conclusion. […] We take pleasure in the music because it states a theme, the theme elaborates itself and then resolves, and we are then as pleased as if it were a philosophical revelation – even though the resolution is devoid of verbal content. (2013,7)

(click to play) bouncing ball experiment: processed home video experimenting wirh feasibility of 'bouncing ball'

(click to play) various continua of content and form were plotted as intersecting axes, and each sequence in the show mapped within these parameters as a way of pre-visualising intermediality

Developing intermedial elements within domain

1 Introducing the element (to the other elements)

Tyrone drinks from a half full glass (p7, live action)

2 Articulating the elements (each one’s components, functions, modes of interaction)

The same glass appears on the screen, larger and then viewed from above (p7 screen)

3 Activating the elements (the elements take action, start to move or change in pattern)

The screen glass, viewed from above, morphs into the ‘spot’ (p13 screen)

The real glass is illuminated by the spot (p13 screen/live)

4 Variations in the elements (once a pattern is established, to alter, or disturb that pattern)

Tyrone picks up a real glass, but puts down a virtual/projected glass (p14 screen/live)

The glass on the screen becomes a hand-rendered drawing of itself (p13 screen)

5 Integrating the elements (combination, interrelation transformation and mutual influence)

Lesley reaches for the onscreen drawing of the glass, and it is transformed into a real drawing on paper as it leaves the domain of the screen. He crumples it. (P14 screen/live)

6 Intermediality brings about a new, integrated state for each element, which can then return to (1) to be reintroduced, rearticulated, reactivated, revariated and reintegrated.

Tyrone notices his real glass has gone. It appears to have been absorbed by the screen. (p16 live action)

Paper drawing of the glass appears simultaneously on the screen as it is uncrumpled (P14 screen/live)

Tyrone speaks and sings a song about a half-full glass (p14 musical/Screen/live action)

Tyrone references the glass being ‘a third-full’ as analogy for optimism (p21 live action)

4 Conclusion

The particular rhythms of this performance work emerged as its intermediality coalesced. Some of these rhythms were captured on the page as line breaks. Many more, which evolved onstage, would remain elusive in performance as simultaneity ruled without a director or dramaturg to marshal and conduct them. We had to embrace the possibility of risk and failure. We had to trust in the developmental work that we’d done to take us to the opening night as each member of the team, by necessity returned to their singular designations of performers and video maker. Though much had happened behind the scenes, the work had been built in only 40 hours of face-to face contact time over one year. There is certainly further research to be done on the rhythmic properties of Composed Theatre, especially when simultaneity is such a feature of intermedial performance.

The process of making Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot was clearly compositional and highly musical. Just as when writing a song, one idea might summon another, or an unexpected image, rhythm or rhyme bring forth another one entirely, so it was with this project. Because these resources of form, content and structure were plastic and provisional, it accelerated the processes of creative evolution, adaptation, recombination, mutation, and extinction that shaped its final iteration.

A congruence of an image, or an inversion or re-placement of an idea informed each fragment and its potential home in an emerging sequence, and a forming whole. Employing provisionality, plasticity and thinking axially about the binaries that framed our work enabled us to locate the edges of our domain and engage in a process largely led by form. The process was kept open enough for emergent to influence the sources from which they had first appeared. This led to the development of an idiosyncratic set of conventions that combined and recombined to make the performance distinct, yet readable for an audience. These principles enabled us to embody Strunk and White’s dictum to ‘Be obscure clearly! Be wild of tongue in a way we can understand’ (2000: 79).

At times the process was abstracted and hard to grasp and at others very simple, concrete and enormously playful. Allowing the performance to emerge and collaboratively engaging with the paradox of looking for something to stumble across (while having faith that something will turn up) not only sums up this particular process, but is also the closest the show came to developing a thematic through-line, in which optimism is superseded by hope, evoked here by Seamus Heaney:

Hope, according to Havel, is different from optimism. It is a state of the soul rather than a response to the evidence. It is not the expectation that things will turn out successfully but the conviction that something is worth working for, however it turns out. Its deepest roots are transcendental, beyond the horizon. (2002: 47)

1.3 Challenges of Intermediality and Composed Theatre

The project was informed by the work of David Roesner and Matthias Rebstock in its definitions of Composed Theatre which embraces both the ‘theatricalisation of music’ and the ‘musicalisation of theatre’ (Rebstock & Roesner 2012: 11). They describe how creatives working on the theatre stage in this mode:

approach the theatrical stage and its means of expression as musical material. They treat voice, gesture, movement, light, sound, image, design, and other features of theatrical production according to musical principles and compositional techniques and apply musical thinking to the performance as a whole. (2012: 9)

The primacy of songs in this project is key to this kind of musical thinking. Songs were the starting point for many of the components of Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot. Songs influenced the interaction of screen and live action, as well as informing the structure of the work. As artefacts dependent upon the interanimation of text and music, songs themselves could easily be considered intermedial. Much of the creative energy in this project came from this play between artforms, the ‘intermedial and/or interartial transference at the heart of Composed Theatre (Rebstock & Roesner 2012: 353). Intermediality is distinct from other ‘medialities’ for its ‘co-relations between different media that result in a redefinition of the media that are influencing each other, which in turn leads to a refreshed perception’ (Kattenbelt 2008: 25). Lehmann (2006: 86) also describes the concept of parataxis operating within intermedial performance, a side-by-side-ness which offers a ‘de-hierarchisation of form’. While songs may have been the aesthetic impetus for the show, there were many instances where their influence became contingent on a range of other factors; when they changed and responded to, rather than dictated the shape of the performance. They were cut, shifted, shortened, remixed and replaced as the performance emerged. In this particular creative process, music and theatre weren’t just superimposed: they were allowed to qualitatively change one another.

The chase for this mutually influential quality of intermediality can be elusive: there’s no recipe for a combination of art forms which will form relationships of mutual influence in performance process and product. Neither can this aspect of intermediality be completely pre-determined because it’s essentially emergent. Just as humans collaborate, combining complementary skills and passions in order to create innovations that neither could individually have brought to being, intermediality could be considered a creative collaboration between artforms.

(click to play) slideshow of sketches created before and during creative development,

sourcing images from lyrics and anticipating 'shoestring' staging effects and illusions

(click to play) an earlier promo, cut together using video sourced from creative development process, Nov 2015

2.2 Music

The show was led by music, namely a repertoire of original compositions created for ukulele, double bass, lead and backing vocals. Unclassifiable as a single genre, they traversed jazz, Tin Pan Alley style ballads, torch songs, comedy songs, absurd musical jokes, instrumentals, and experiments with found text. Almost all had been recorded on four independently released albums over the preceding five years. Many had been road-tested with audiences on stages designated for both theatre and music while some were new, unrecorded compositions. While they contained lyrics, we treated them ‘as music’. Wolf observes that a song ‘...is a rare example where overt and covert music-literary intermediality coincide’ (1999: 187). Suzanne Langer tells us that:

‘When words enter into music they are no longer prose or poetry, they are elements of the music […] they give up their literary status and take on purely musical functions […] song is music.‘ (1953: 150–152)

This musical materials in the show extended well beyond the 18 songs that ended up in the final version. Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot was rarely silent, with both musicians providing live accompaniment to interstitial spoken word, and two occasions of pre-recorded original instrumental music, played in sync with projected images.

2.3 Screen

In Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot, the screen presents ‘as itself’; that is to say it is clearly framed as a projection surface. There is at first, no illusion at play. The projected images are projected images. However the creative development of the work quite literally deepened and broadened the role of the screen in the work.

A central idea that appeared early in the development was that the project would play with ambiguity between the ‘perceived’ and ‘actual’ edges of the screen, meaning that the video content (issuing from a single projector) would be ‘projected across an area larger than the projection screen, hitting areas of the wall or curtains behind’ (Megarrity & Sibthorpe 2016).

Other variations we found included play with the perceived transparency of the screen (that is, the illusion of people or objects being visible ‘through’ it); its ability to transform objects on the basis of their size, scale, style of representation or resemblance to other objects, and its ability to interact with the physical performer, to reproduce images of itself and potentially create other spaces for the performers to appear in. For example, when the ‘live’ Lesley leaves the stage and ‘reenters’ on the screen, reduced in size during the Unaccompanied sequence (Megarrity & Sibthorpe 2016: 20).

In certain sequences the screen (and by extension its operator) worked as a third member of the ensemble, working rhythmically with the musical elements. At other times it performed as antagonist, obstructing the work of the human performers to comic effect.

Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot became a 60-minute intermedial show combining music and screen in performance. Created very cheaply and presented by only three people (two performers and a video artist) the show is ostensibly a simple music gig supported by basic use of concert visuals, presented on a vintage screen.

Tyrone and Lesley are the performance personae of David Megarrity (writer/composer/performer, ukulele) and Samuel Vincent (composer/performer, double bass). Versatile and responsive to new performance conditions, these two have presented numerous shows on theatre and music stages (Megarrity 2002, 2012, 2014). Projections were created by videomaker Nathan Sibthorpe, principal collaborator and a co-writer of the project. This new show was conceptualized as being driven by original songs, ostensibly a concert presentation, but in fact an instance of what Werner Wolf would term ‘covert intermediality’:

As opposed to direct or overt intermediality, ‘covert’ or indirect intermediality can be defined as the participation of (at least) two conventionally distinct media in the signification of an artefact in which, however, only one of the media appears directly with its typical or conventional signifiers and hence may be called the dominant medium, while the other one (the non-dominant medium) is indirectly ‘present’ within the first medium (1999: 41)

In plain language, what seems like a very simple musical presentation, accompanied by some visual elements, eventually reveals a much more complex intermedial performance, without pointing to, or advertising that complexity. In the show, Tyrone and Lesley play original songs on ukulele and double bass, alongside projected images. At a glance it might look like Post-Vaudeville. There is little backstory or exposition. The performers are clearly aware that they are employing these apparently lame production elements to enhance the quality of their regular presentation.

Each song is framed by the patter Tyrone offers in the mode of generative narrator. This performative text was composed last and is comprised of minimal, reflexive spoken words which point to elements of the show, or set up the song to come. Lesley most usually is a non-verbal, but no less expressive presence.

Elements of song, image, text and action often drew on the natural world as well as elements of domestic interiors and the stage environment itself. These images, spoken as text, sung as song, or projected as pictures, progressively combined and rearticulated, influencing one another to reveal that the attempts ‘Tyrone and Lesley’ are making to enhance their show with spectacle, have become their own kind of spectacle (and perhaps aren’t fully under their control).

A free-standing vintage collapsible screen is the surface upon which images are projected. Some are still images, and most are animated. Some involved pre-shot live action, allowing the performers to leave the stage and apparently ‘enter the screen’. This screen’s default state is the eponymous white spot (transformable into a spotlight, moon, or the sound hole of a ukulele) on a dark background. The projections actively play with perceptions of borders and edges; that is to say, where the image appears to, and actually begins and ends.

The project began as a pure creative development, fuelled by optimism, with no particular performance outcome in sight. This scattered, part-time collaborative process happened in person, on paper and virtually over six months in 2015 at Metro Arts, a multidisciplinary arts organisation housed in a heritage-listed warehouse in central Brisbane. This period of writing construction and experimentation culminated with a work in progress to an invited audience. The work was then selected for the Queensland Cabaret Festival at the Brisbane Powerhouse and premiered in June 2016.

The performance was noted by Katherine Sullivan in thecreativeissue as a show that ‘doesn’t try to hide anything […and] combined music with moving images to create a cabaret show that is […] absurd and very charming’ (2016). Rhumer Diball pointed out that ‘Sibthorpe’s projections were used not only as accompaniment, but as a third character’ (2016).

3 Principles of intermedial performance making in composed theatre

3.1 Provisionality and plasticity of structure and form

A key feature of this process was provisionality – this ‘for-the-time-being-ness’ that allowed the artists to respond to new ideas, yet not necessarily be constrained by preconceived outcomes or the project’s resource limitations.

This quality was largely pragmatic. There was little time, and even less money, so the ideas had to be good. The initial components of the show offered clarity. Songs, spoken words, screen, projected image, two bodies onstage, one body off. We quickly came to discover that these known quantities generated a field of variables and potential well beyond what we’d initially anticipated. This was a good thing, of course, yet it instantly challenged our abilities to realize the ideas we were generating.

In this creative state the thumbnail sketch, the low resolution preview, and the quickly shuffled setlist are likely to be of more use than a more fully rendered version of an object, especially if the process of perfecting the draft is likely to slow or arrest the creative development. I refer to this as a ‘cardboard and sticky-tape’ approach. If you’re looking for emergents, insisting on perfection will inhibit their emergence.

This involves quick assembly and easy disposal. For instance, as we attempted to capture images as if shot from the inside of a ukulele, an improvised rig of coat hanger, cardboard box and masking tape were attached to the camera to frame the illusion. The film crew were also the writers and in my case the performer as well. Working quickly and dirtily, I noted: ‘We’re less concerned with getting it right than getting it at all.’ Nathan Sibthorpe suggested our approach at that stage was not only two-handed, but also ‘to-handed’, citing Heidegger who:

believes that we experience the world of objects from the standpoint of to-handed-ness or Zuhandenheit, considering everything as something we might be able to use, pick up and manipulate, even if we cannot physically do so with our bare hands. (Jaquette 2015: 246)

The initial physical properties we’d given the show delineated the onstage resources we had to deal with very clearly. However as we generated more and more layered fragments out of the music, and developed the visual and symbolic order of the piece, what we had ‘to hand’ naturally increased as the show generated its own aesthetic resources and conventions. In this way, the emergent may inform, transform, or speak back to their origins. This process also dislocated the act of writing from text on page generated by a nominated ‘writer’ and enabled it to occur in various other places, and various ways.

3.3 Creating within domain

De-throning the script as the sole location of writing, not setting out to make the show ‘about’ anything, eschewing traditional narrative structures, and avoiding character in favour of persona allowed the emerging intermedial performance to retain a more musical than theatrical quality. It can be difficult to describe quite how this quality can be derived in a creative development process, especially when Composed Theatre can be so idiosyncratic and music itself is resistant to capture through language.

Reading around the work, I discovered Katz and Gardner’s work (in Hargreaves, Miell & MacDonald 2012) on deepening stage theories of creativity, with particular regard to composers. Here they describe two differing approaches to composition (especially its initial creative stages): within domain and beyond domain.

The composer taking a beyond domain approach begins work with an extra-musical idea, something outside of the domain of music. This refers to a broader context or purpose of the piece – for example to celebrate or evoke a civic occasion, or translate something from another art form into music. In contrast, the within domain composer:

concentrates on the musical materials themselves […] by focusing on small snippets of music in a hands-on fashion. These composers allow these materials to sink in for long periods of time until the illumination stage; at that point they rely heavily on kinaesthetic memory or instinct vis-a-vis their instruments as a means of launching the initial bits of sound into a more coherent work. (cit. in Hargreaves, Miell & MacDonald 2012: 110–1)

The ‘world’ of the piece was brought to us by the songs. These now intermedial fragments of an as-yet unresolved whole were treated in modes more akin to musical composition than dramatic construction. As each fragment gained shape and layers (musical, visual, performative) and the symbols of the work consolidated, we gained a growing sense that there would be a fugal flavour to the work, as images interspersed through the work reiterated, reflected upon and chased each other.

Therefore we were building our own conventions, the show seemingly self-structuring and telling us what it wanted to do (rather than the other way around) with its visual language harvested from both the symbolic order already embedded in the songs and the stage environment they were performed in. At times, these conventions started to alter the very sources from which they had emerged. Songs shifted to suit the circumstances in which they were to be sung. Jaegwon Kim suggests one view is that the emergents can ‘bring into the world new causal powers of their own, and, in particular, that they have powers to influence and control the direction of the lower-level processes from which they emerge’ (in Bedeau & Humphreys 2008: 129) and this was true of Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot.

Video maker Nathan Sibthorpe talked about the ‘architecture of the piece having its own language’ in its digital compositions, the images it represented and the way they moved, transformed and integrated with the other elements. The titular ‘spot’, first intended as a visual pun, became a locus for new ideas as it began to behave in unexpected ways, and reveal its potential as an active player in the work. All other elements of music and performance experienced similar shifts as they interacted within the domain that the work had generated for itself. This revealed a cyclic process of development that began on the page, but found its fullest realisation in performance, as described below in a selected instance of the ‘glass half full’ which is traced through its various intermedial iterations.

Each cycle of this activity was built around key symbols and devices which emerged. While far from precise, it settled into a system of gently obvious, yet no less pleasurable illusions and ‘reveals’ that gradually exposed the complexities of formal play, and metaphorical depth of the piece.

3.4 Axial Thinking

Just as our development of screen content in the creative work played with the perceived and actual edges of the projected image in order to create a new work ‘within domain’, we surely had to develop a sense of where this ‘domain’ actually begins and ends. While there were some known qualities at the beginning of this creative process (such as the general nature of the music, and the presence of the screen) much was unknown, and even more of that potential knowledge was relational – in that the qualities of each element would come to rely on one another for definition.

As such, we devised a set of continua: a set of either/or dichotomies of artistic form. For example, we knew that at times music may lead screen content, but at others screen content may lead music, so we nominated a continuum from ‘concert visuals’ to ‘live soundtrack’. There were many of these apparent binaries to begin with, and we discovered more as we experimented further. We ended up with thirty variations – an unworkable proposition which we whittled down to ten active properties, a process of creative triage which clarified the process significantly:

Concert visuals <> Live soundtrack

Attempt at spectacle <> actual spectacle

Multimedial <> intermedial

Theatrical <> performative

Predetermined <> emergent

However, we found these continua could not comfortably be ‘stacked’ or operate in parallel. The performance objects we were constructing tended not to be ‘either/or’. They were mostly ‘and’, and ‘as well as’. As we sought to align them we realized that a more likely arrangement for these continua would be one of intersection. Each sequence could be plotted and positioned across these intersections.

Intermediality of course entails exactly these qualities of between-ness, amongst-ness, and together-ness. This liminality inspires a kind of axial thinking, as Brian Eno puts it, which:

doesn’t deny that it could be this or that – but suggests that it’s more likely to be somewhere between the two. As soon as that suggestion is in the air, it triggers an imaginative process, an attempt to locate and conceptualise the newly acknowledged grayscale positions. (1996: 298)

In the development of Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot, for example, sometimes an illusion was as effective as intended, and at other times the attempt would be quite deliberately inept. Much of the time the dynamic was somewhere in between.

We found these, and other variables intersected in ways that endowed each sequence with its own distinct qualities. We laid these continua across one another and mapped each of the sequences in relation to this new interaxial way of viewing the development. We then animated the images to illustrate the progression across the structure of the whole work.

While axial thinking offered nothing like the comfort of a map or even stable topography, it further facilitated intermedial play ‘within programmatic parameters’ which Harvie and Lavender (2010: 14) suggest characterizes this devising, and gave us some reason to hope it would coalesce into something other than its parts. This system essentially clarified (without directing) the process of constructing Tyrone and Lesley in a Spot.